The Consumer Is Ready To Spend

“Coiled, ready to go.” is how JPMorgan CEO Jamie Dimon described consumers last week. “Consumers have $2 trillion in more cash in their checking accounts than they had before Covid.” he added. Borrowers are in such good shape that JPMorgan reported a 4% drop in loans when they released their quarterly earnings. Stimulus cash is being directed towards debt repayment.

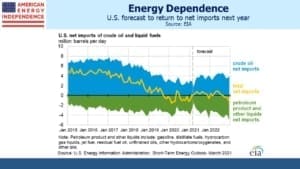

The inflationary result of a consumer spending boom and low interest rates is the biggest uncertainty confronting investors. There’s plenty to worry about. Federal debt:GDP is set to exceed the levels that followed World War II. The level of Covid stimulus is several multiples of the estimated loss in output. Larry Summers, who headed the National Economic Council under Obama and was Clinton’s Treasury Secretary, has called it “substantially excessive,” and in case his views weren’t clear added that fiscal policy is the “least responsible” in 40 years.

Rising inflation shouldn’t catch anyone by surprise – and sure enough March CPI jumped 0.6%, 2.6% year-on-year. Ex-food and energy it was only 1.6%. Will this be sustained, and at what point will the Fed feel compelled to react?

The base effect – a depressed March 2020 CPI because of the sharp economic contraction – means annual comparisons will look high for several months. This will not trouble the Fed. Prices for all kinds of commodities are rising – hot rolled steel has tripled in a year, and while this reflects a rebound from severely depressed prices, it’s also more than doubled compared with two years ago. Copper, lumber and carboard tell similar stories.

March Retail Sales jumped 9.8%, boosted by spending at bars and restaurants as restrictions are being eased.

Moreover, many small businesses report trouble hiring people, in part because the recent $1.9TN Covid relief plan continues $300 per week Federal unemployment benefit on top of whatever the state pays.

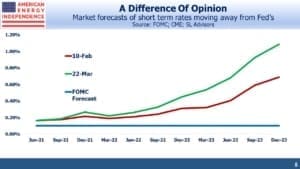

Although signs of pricing tightness are everywhere, a review of Fed chair Jay Powell’s comments on inflation show numerous reasons to ignore them. Year-on-year comparisons simply reflect a rebound from sharply depressed levels. Tight commodity prices are a function of supply challenges that are being erased as people return to work. Consumers’ spending power will boost demand for a few months before dissipating.

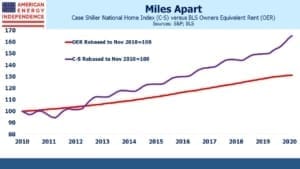

Moreover, the Fed will never react to housing inflation, because house prices don’t figure in CPI, or the Personal Consumption Expenditures (PCE) index, their preferred measure. Owners Equivalent Rent (OER), the survey of what homeowners think they could rent their house for, doesn’t track house prices and doesn’t reflect any actual transactions (see Why You Can’t Trust Reported Inflation Numbers). So it’s a meaningless index, and because of the weight OER occupies it artificially depresses CPI by 2% and the PCE index by 1%.

Finally, although the unemployment rate is 6%, it was 3.5% in February 2020 with no discernible impact on inflation. Given the Fed’s focus on ensuring maximum employment, they’re unlikely to raise rates before unemployment drops at least that far again, unless there are clear signs of wage pressure. Any tapering of bond buying is likely to await actual evidence of inflation. This is a subtle but important shift – the Fed isn’t going to act based on a forecast of inflation. They plan to be late.

Financial advisors have few tools with which to protect against rising inflation. Shorting bonds is inefficient because of the large amounts needed to create much protection, and few are licensed to use interest rate futures for clients. Stated inflation is also likely to lag the actual inflation experienced by most people, due to the flawed use of OER noted above.

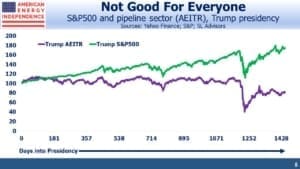

Not surprisingly, since this is a blog focused on the energy sector, pipelines are one of the few sectors that offer meaningful protection. Dividends are stable, yielding 7%. Announced buybacks across the sector add up to a further 2% return. A drop in yields to 6% would add another 14% in appreciation, so a one year return of 20% or more (7+2+14) is plausible.

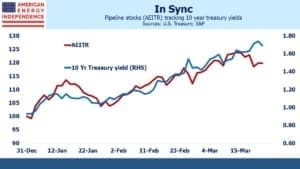

In addition, pipelines have tracked the ten year treasury yield reliably this year, with both rising together during 1Q21 and both moving sideways more recently. And if the Fed moves too slowly once inflation finally appears, the commodity sensitivity embedded in midstream energy infrastructure should provide additional upside.

We are invested in all the components of the American Energy Independence Index via the ETF that seeks to track its performance.