Criticism Of The Fed Goes Mainstream

Earlier this month there was a fascinating exchange on Bloomberg TV between former NY Fed president Bill Dudley and journalist Jonathan Ferro. Dudley has been vocal in criticizing the slow rate at which his former FOMC colleagues have been normalizing monetary policy. He’s pointed to the robust stock market and warned that the Fed’s going to tighten financial conditions enough to push up the unemployment rate. Ferro, refreshed by the frank analysis and used to more guarded responses from Fed officials, asked Dudley “why Fed officials don’t talk like you?”

Dudley responded that it’s unpleasant to talk about how you have to push up the unemployment rate and put people out of work, even though that is the Fed’s goal.

The Fed wants tighter financial conditions. This needs to manifest itself via higher long term yields, since sectors like housing and capital spending are more sensitive to the ten year yield than the Fed Funds rate. And the Fed needs a weaker stock market, because households that feel poorer will spend less, cooling things down. It is truly an unpleasant prospect. Covid has receded other than a few remaining constraints – Broadway shows still require masks and travel outside the country may still leave you stranded if the required Covid test before re-entry is positive.

But with 3.6% unemployment the vast majority must be better off, and happier, than they will be once the Fed engineers tighter financial conditions and the consequent economic slowdown. On Thursday, Fed chair Jay Powell said, “It’s absolutely essential to restore price stability. Economies don’t work without price stability.”

Ten year yields are approaching 3%. Compared with 8.5% annual inflation Bill Dudley notes that policy remains very loose. But yields are edging up, helped by Fed officials warning of successive 0.50% rate hikes, as Powell did last week.

The stock market isn’t helping much, even after last week’s sell-off. For the first time in a decade, the Equity Risk Premium (ERP) doesn’t make stocks look cheap. The 5.4% earnings yield, based on Factset bottom-up figures, versus a 2.9% ten year yield puts the ERP at 2.5, right on the average since 2000 when the dot.com bubble burst.

Earnings forecasts are being revised higher, reflecting little evidence of any influence from the Fed. Analysts still expect growth next year of 10%. But a 3.4% ten year yield in 2023 would be enough to keep the ERP at 2.5. By this measure, stocks are as expensive as they’ve been in the past decade. Tighter financial conditions include a weaker stock market according to Bill Dudley. If the stock market repriced to its average ERP of 3.3 over the past ten years, that would imply the S&P500 around 15%, lower.

When a liberal-leaning magazine such as The Economist blames today’s inflation on the Democrats pushing through last year’s $1.9TN stimulus, you know it’s conventional wisdom. Larry Summers must be a thorn in the side of the White House, since he warned of such as the package was being debated and hasn’t let up since. This week’s Economist analyzes the Fed’s “historic mistake on inflation” and includes a special report on central banks. They blame the Fed’s modified interpretation of its mandate to allow higher inflation, along with institutional groupthink that assumed stable prices were hard-wired into the economy.

The Economist also notes that central banks have taken on a broader remit in recent years. In the US progressive Democrats wanted that to include policies to counter climate change. Fed candidate Sarah Bloom Raskin withdrew her nomination when Senate Republicans objected to her past comments pushing the Fed to withhold pandemic support from fossil fuel firms.

However, the Fed does now seek maximum employment that is “broad-based and inclusive”. Powell explained the shift thus: “This change reflects our appreciation for the benefits of a strong labor market, particularly for many low- and moderate-income communities,”

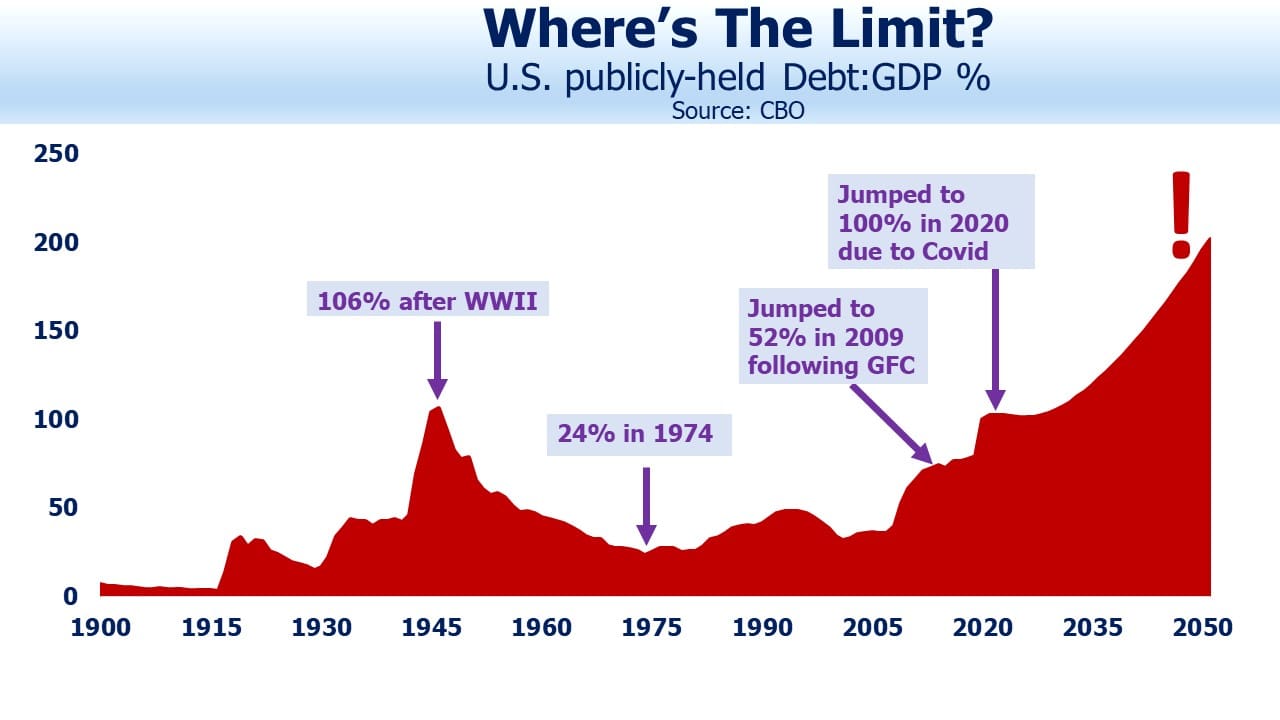

There is evidence that minority unemployment, which is always higher than for the general population, rises faster during a slowdown. This will be a consideration in the background when the FOMC is facing rising joblessness but has not yet conquered inflation. Debt:GDP is the most important reason America will learn to live with higher inflation, since it allows lower or negative real rates which makes it cheaper to finance. But the mix of unemployment will also play a role in FOMC thinking.

On Saturday I had the good fortune to play golf with Bill Dudley. He denied that he was captain of the Federal Reserve golf team, in spite of what I saw as evidence in support. We spent much time exchanging views on Fed policy and the outlook for rates. Dudley thinks the happy combination of declining inflation and a rate cycle peak of around 3%, as laid out in the most recent FOMC projection materials, will be hard to achieve. I think if Dudley was on the FOMC today they would have acted against inflation in a more timely fashion.

The Fed has committed the biggest inflation mistake in its history. The FOMC won’t concede such, but their hawkish shift shows it was obvious before The Economist made it official. They’re still a long way from creating tight financial conditions. Leave the bond market to those who tolerate returnless risk.

We have three funds that seek to profit from this environment:

Energy Mutual Fund Energy ETF Real Assets FundPlease see important Legal Disclosures.