Pipelines Close In On A Milestone

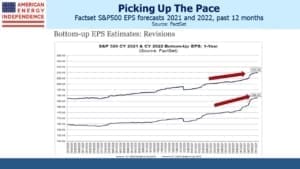

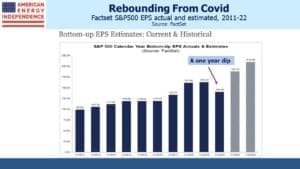

The S&P500 is up 11% so far this year. 2021 EPS estimates from Factset are up by close to the same amount. The rise in ten-year treasury yields means the Equity Risk Premium (ERP) doesn’t show the market to be quite as cheap as it was, but not by much. Covid has been less traumatic to the market than to people. Earnings forecasts have been rising steadily for the past six months. First quarter announcements led to a surge in upward revisions.

2021 S&P earnings are now expected to be 15% higher than pre-Covid 2019, a 7.3% compound annual growth rate over the two years. Enormous fiscal stimulus in the U.S., which continued even while vaccine distribution was letting life return to normal, helped. 2022 earnings growth of 12% confirms the strong recovery.

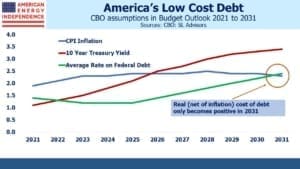

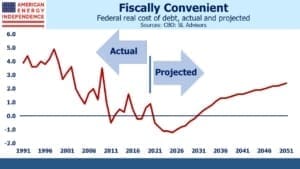

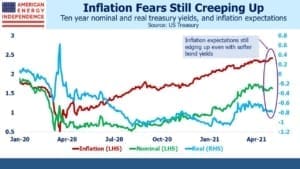

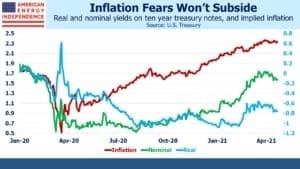

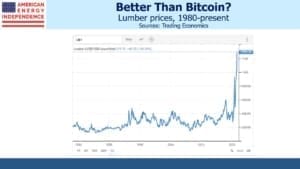

Stocks offer some protection against inflation. But rising bond yields could negate that. The Federal government is on a well-orchestrated mission to drive stocks higher. More $TNs in spending are coming, for investment in infrastructure followed by the American Families Plan. The Federal Reserve’s bond buying is muting the message from investors worried about such fiscal profligacy. Donald Trump, who often took credit for strong stock market performance, must grudgingly admire the government’s synchronized and powerful boosting of equity markets.

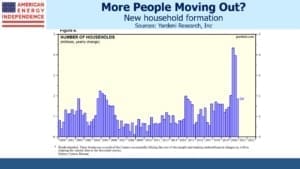

Larry Summers continued his criticism of the Fed, warning yesterday of the Fed’s “dangerous complacency” regarding inflation. He continued, “It is not tenable to assert today in the contemporary American economy that labor market slack is a dominant problem. Walk outside: labor shortage is the pervasive phenomenon.” That view fits the facts as we see them better than the Fed’s outlook.

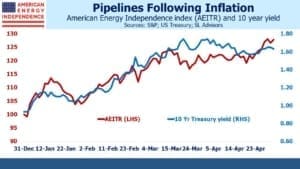

Although the market has continued its upward momentum, there’s been a clear rotation away from growth and towards value. Rising bond yields has contributed to this – growth stocks in effect have a longer duration, increasing their sensitivity to higher rates. The IWM/QQQ ratio compares small cap value with technology stocks. The trend for value to outperform began with the vaccine announcement in November.

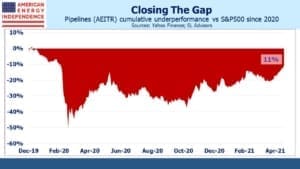

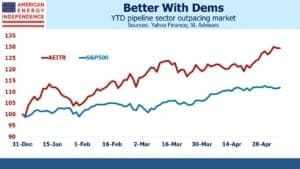

The perennially unloved energy sector has been inexorably recovering too. North American pipelines, as measured by the American Energy Independence Index (AEITR), have been gradually closing the performance gap with the overall market. It’s increasingly clear that the brief collapse in March 2020 was partly due to the forced liquidation of leveraged closed end funds (see MLP Closed End Funds – Masters Of Value Destruction). The biggest pipeline corporations delivered 2020 financial results that weren’t far from pre-Covid guidance. Reduced spending on new projects helped, and operating cashflow for the sector offers unappreciated resilience.

A handful of natural gas pipeline operators then benefitted from the Texas power cuts in February, when prices spiked over 100X. The sector even rallied when the Colonial pipeline suffered a temporary service interruption, causing gasoline shortages in parts of the eastern U.S. (see Hackers Highlight Pipelines’ Value).

The International Energy Agency published a report on what the world needs to do in order to reach zero emissions by 2050. Their recommendation is that no new supplies of oil, gas or coal be developed. This is implausible – China, India and other emerging economies aren’t going to abandon their plans to raise living standards and energy consumption (see Why The Energy Transition Is Hard).

Investors are coming to terms with a more realistic assessment of the energy transition – one recently articulated in an excellent paper by JPMorgan’s Mike Cembalest. Solar panels and windmills can’t meet all the world’s energy needs, which are likely to keep growing as emerging countreies seek higher living standards for their populations.

The pipeline sector has continued its post-Covid bounce and is within 11% of matching the return of the S&P500 from the beginning of last year, when few knew what a coronavirus was. Inflation fears, which continue to percolate, have helped push commodity prices higher. This, combined with the strong recovery, is also boosting oil and gas prices. If current trends continue, the AEITR will close its 2020-21 performance gap with the overall market, which would represent another milestone in its recovery.

Sentiment, based on our many client conversations, is turning cautiously optimistic. The past several years of disappointing returns dissuade many generalists. Energy buyers haven’t been accused of irrational exuberance for a long time.

Free cash flow yields that should exceed 10%, 2X the S&P500, by year’s end, should continue to drive strong returns.

We are invested in all the components of the American Energy Independence Index via the ETF that seeks to track its performance.