Not All Growth Projects Are Good

Kinder Morgan (KMI) kicked off pipeline earnings season last week, as they do every quarter. Their adjusted EBITDA came in a little ahead of expectations at $1.97BN vs $1.95BN. Management guidance was positive.

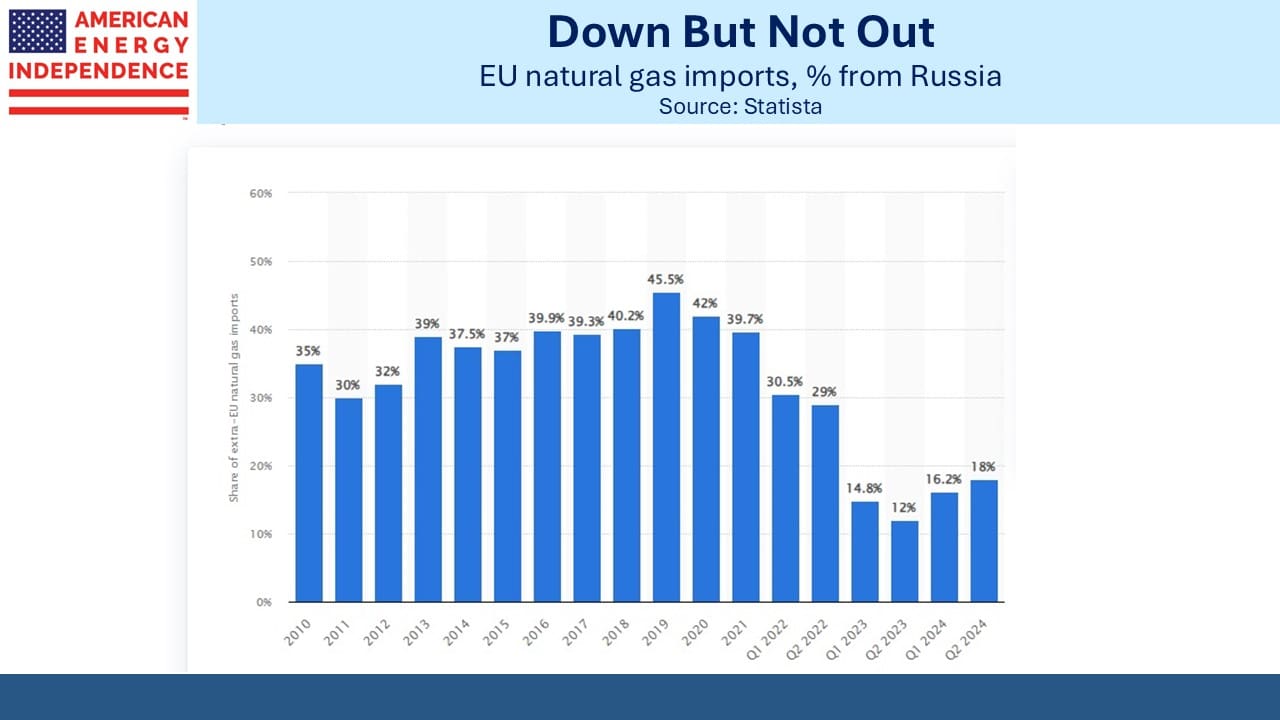

LNG exports and data center power needs are the two growth drivers for natural gas pipelines. KMI’s Trident Intrastate Pipeline secured another customer for 0.5BN Cubic Feet per Day (BCF/D). Trident serves the Golden Pass LNG terminal on the Texas side of Sabine Pass, opposite Cheniere’s Louisiana-based terminal.

KMI also registered some growth from data centers.

The company’s backlog of projects grew by $0.5BN to $9.3BN.

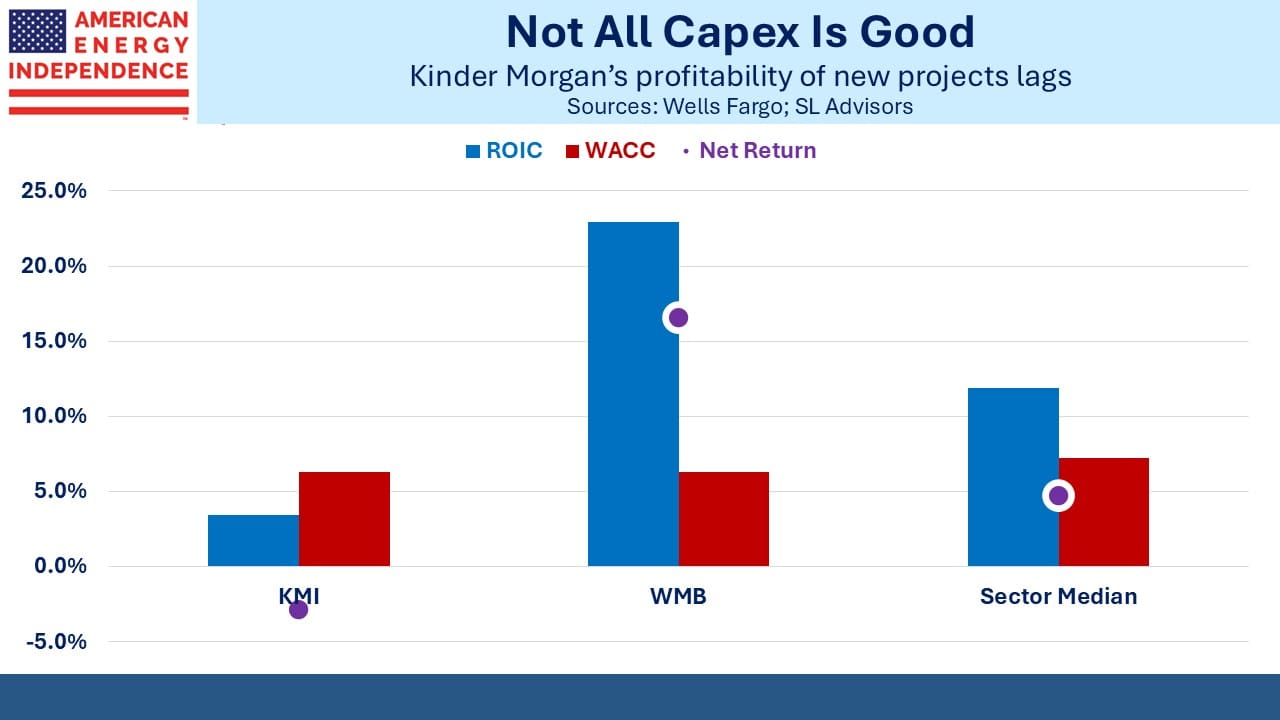

Growth projects are intended to excite investors, because they’re supposed to boost earnings. Reinvesting retained earnings into the business to earn a Return On Invested Capital (ROIC) above their Weighted Average Cost of Capital (WACC) is how companies grow their profits.

Every year or so Wells Fargo publishes Show Me The Money in which they compare ROICs for midstream companies. Its release is probably not greeted with boundless enthusiasm by senior executives at KMI, because they have ranked poorly for years. In the most recent edition (October 2024), they were dead last, with a 25-year average ROIC of just 5.4%.

For the 2018-23 period Wells Fargo calculates KMI’s ROIC at 3.4%, worse than all their peers except Plains All American. With a 6.3% WACC, they’re earning a –2.9% spread. This suggests that on average, KMI investors would be better served if the company hadn’t made those investments.

It’s not a perfect scorecard. Wells Fargo notes that KMI had some natural gas pipeline contracts that matured and were renegotiated at lower rates. Maybe those projects were done twenty years ago and so shouldn’t reflect on more recent capex. Nonetheless, KMI’s returns have been consistently poor. It means that the enthusiasm with which management describes their $9.3BN backlog should not be shared by KMI investors.

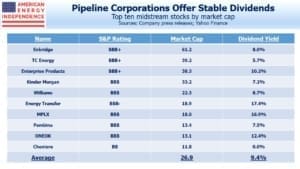

By contrast Williams Companies (WMB) has done a much better job at reinvesting earnings. Their 25-year ROIC is 12%, and 2018-23 is 22.9%. With an assumed WACC identical to KMI, that’s a 16.7% net return. The median company in the sector has an ROIC of 11.9% and a WACC of 7.2% for a net return of 4.7%.

We’ve thought for years that KMI doesn’t earn enough on its capex. We engaged with the company in early 2020 (see Kinder Morgan Responds to our Recent Criticism). When Kim Dang became CEO in 2023 she said, “A large part of my job is going to be about continuity.” As she was previously president and CFO, Dang can’t escape responsibility for the capex decisions that led to those poor returns, and continuity might not be what’s needed to improve results.

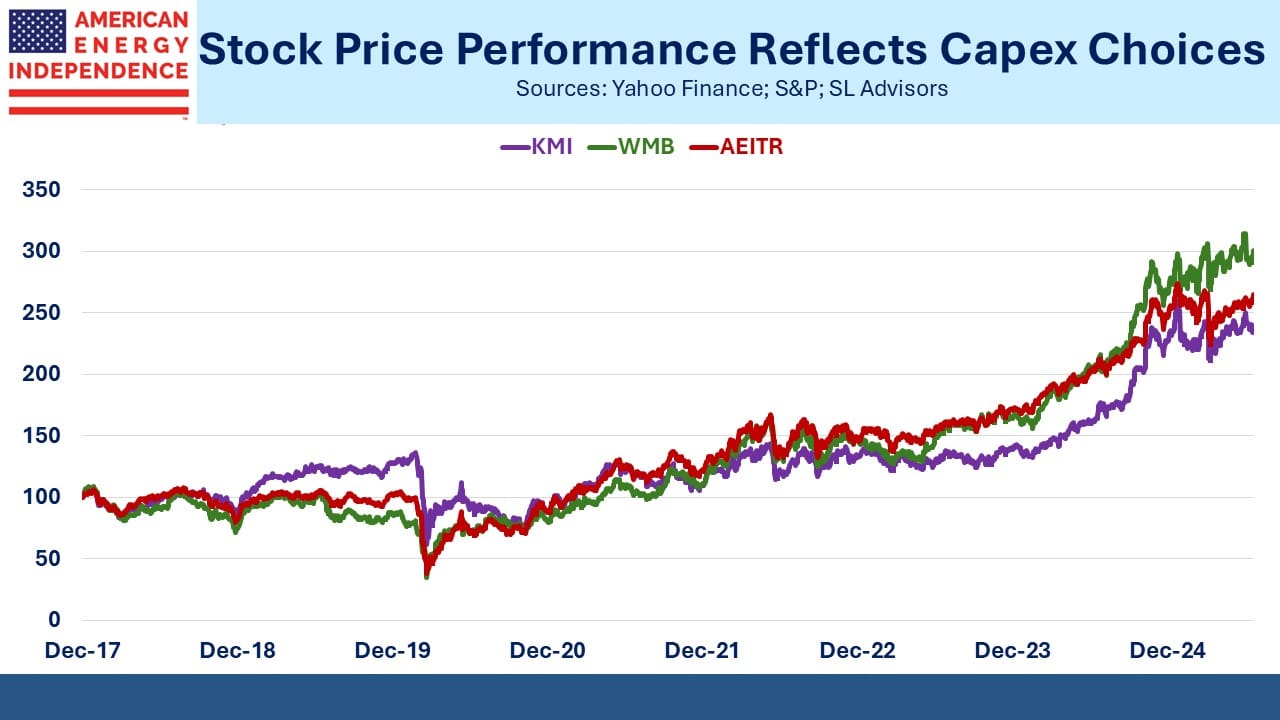

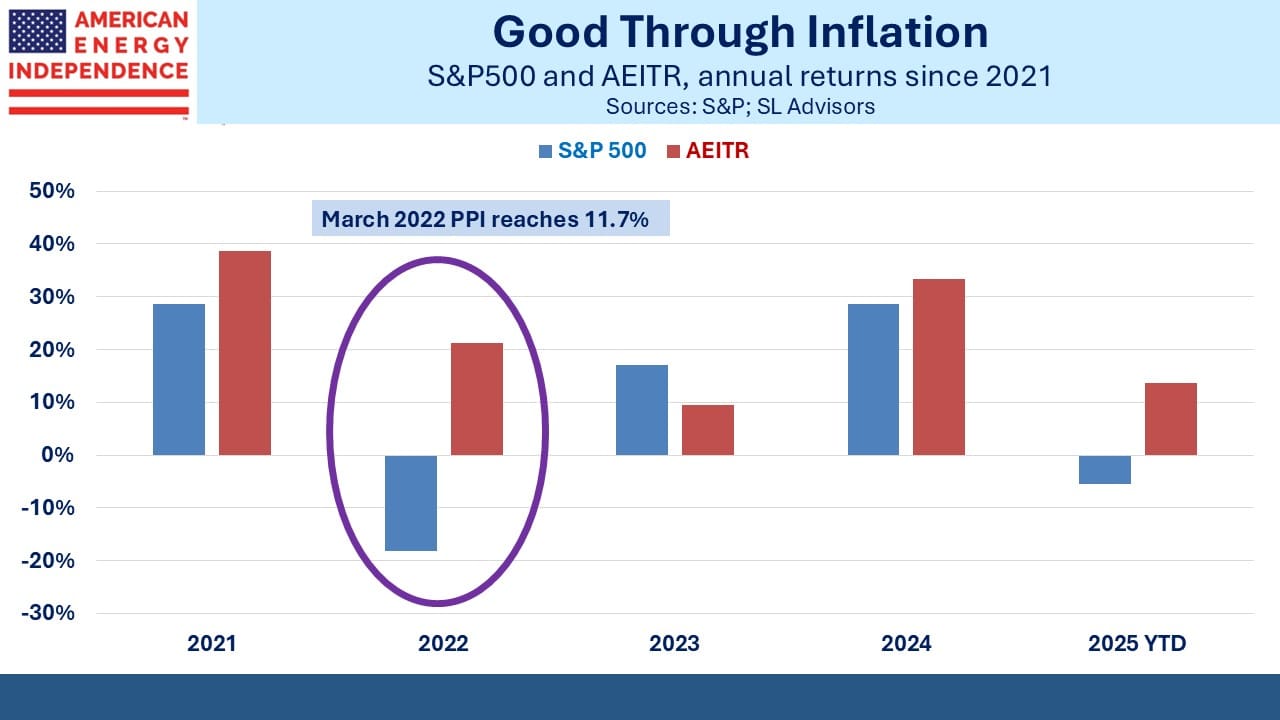

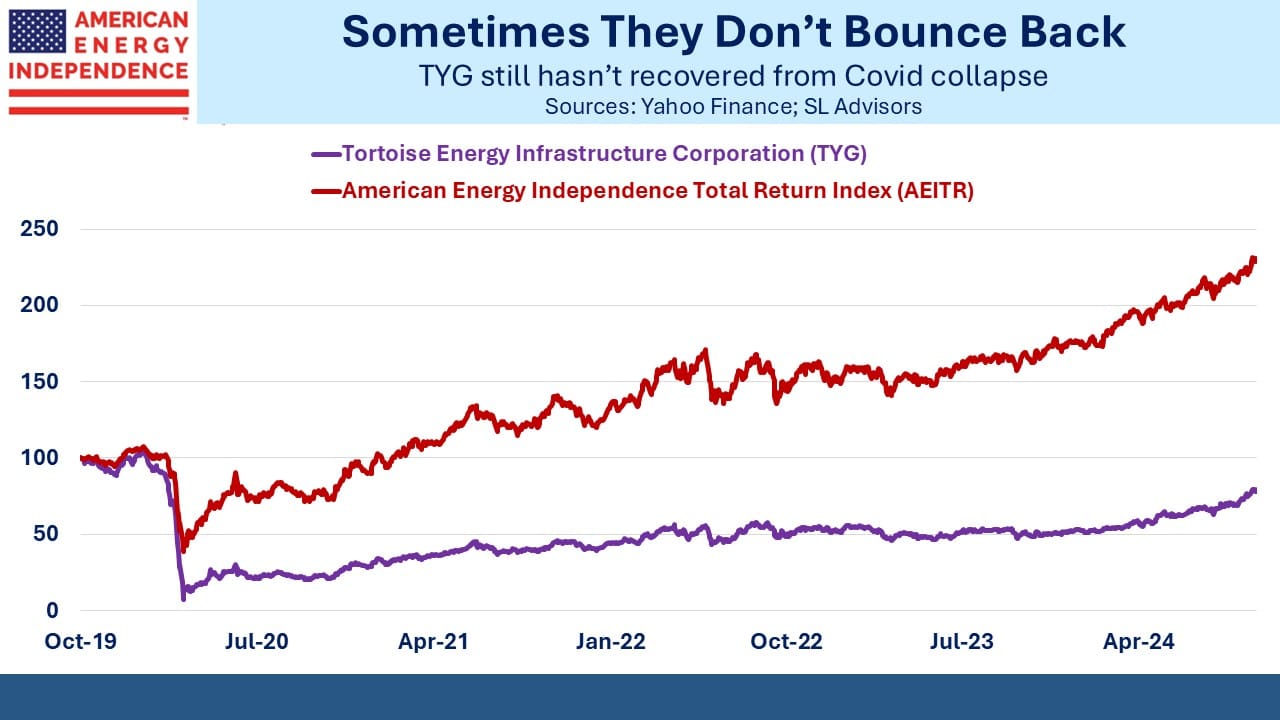

Since 2018, the most recent five-year period covered in Show Me The Money KMI’s stock price return of 11.9% pa has lagged both the sector’s 13.4% pa as defined by the American Energy Independence Index (AEITR) and peer WMB’s 15.2% pa.

Over the past decade, KMI stock has returned 2.2% vs 9.4% for the sector.

Consequently, KMI is cheaper than WMB. On an EV/EBITDA basis KMI is 11.5X and WMB 13.0X. KMI’s Distributable Cash Flow (DCF) yield is 8.7% and WMB’s is 7.1%. The market has long imposed a valuation discount on KMI because of its poor ROIC. The question investors must ponder is whether the discount is sufficient. A company that consistently earns less than its cost of capital is destroying value on new money invested.

Investment decisions don’t have to be binary. There’s a range of possible outcomes and overconfidence is a common error. You don’t have to love a stock or not own it. Positions can be sized with precision based on your confidence and the risk/reward. We’re invested in both names but have more exposure to WMB. KMI may improve its capital allocation and it is cheaper. But WMB has a better track record. KMI is likely to trade at a valuation discount until they can improve their performance.

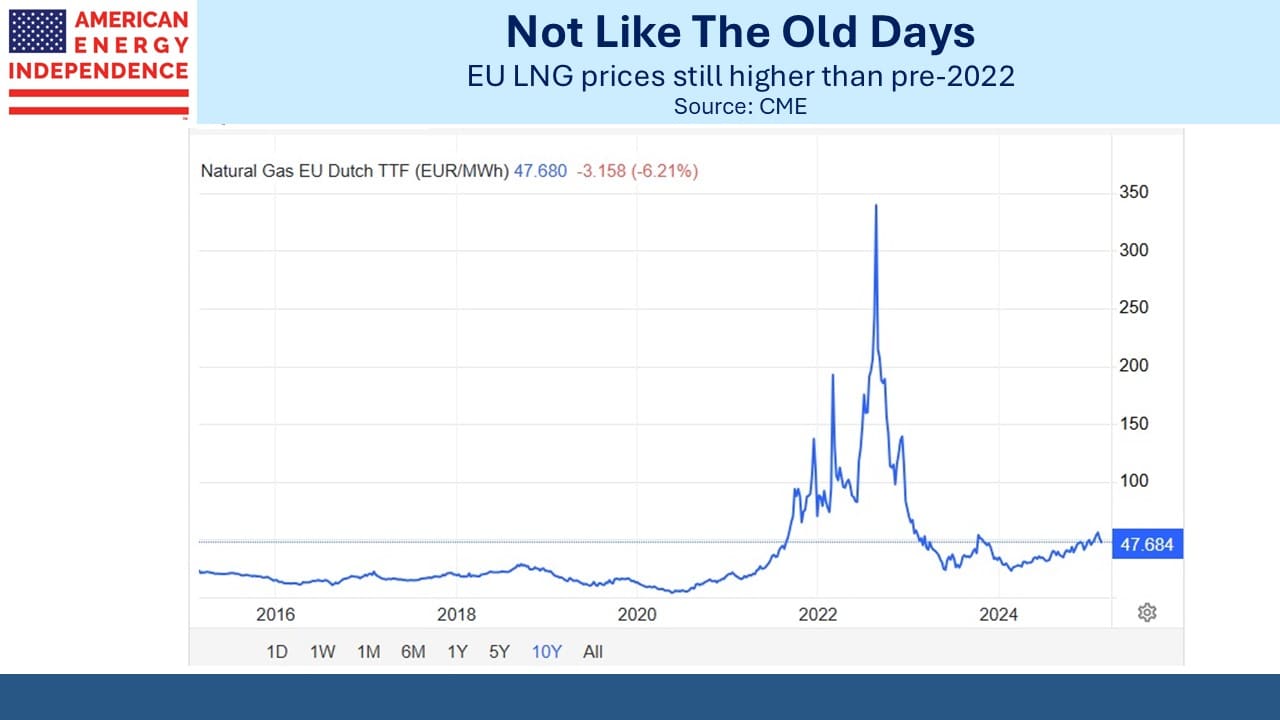

In other news, Italy’s Eni signed a 20 year Sale and Purchase Agreement (SPA) with Venture Global, demonstrating continued strong demand for US LNG. It was ENI’s first long term agreement with a US LNG exporter.

Asian buyers continue to pursue increased purchases of US LNG to reduce trade tensions.

And NextDecade’s (NEXT) stock continued to appreciate as Morgan Stanley’s bullish report of July 11th has drawn more buyers. It shows the impact some analysts can have, because there haven’t been any news developments to affect NEXT recently, beyond Morgan Stanley’s upgrade. Nonetheless, the impact has been as powerful as any recent positive development.

We have two have funds that seek to profit from this environment:

Energy Mutual Fund Energy ETF