Fed Hikes Inflation Outlook By 1%

Fed chair Jay Powell appeared slightly less confident at Wednesday’s press conference. He acknowledged that their forecast of temporarily higher inflation might be wrong, and it was hard to say when it would moderate. He repeated his warning that, “forecasters have much to be humble about.”

This humility must apply to the Fed. One of the most striking updates in the Summary of Economic Projections was the FOMC’s upward revision to 2021 inflation, from 2% in March to 3% now. In his March press conference, Powell spoke about upward price pressures over the near term but assured there would be only “transient effects on inflation.”

Clearly FOMC members were surprised by the inflation reports since then, hence the sharp upward revision. They’re not good at forecasting — certainly no better than a below average private economist. But FOMC forecasts matter because monetary policy and the ongoing debt monetization are managed with reference to those forecasts of moderating inflation.

Powell often downplays the dot plots even while the media examines them in detail for comparison with interest rate futures. Seven out of 18 FOMC members expect at least one rate hike next year, up from four in March. The median of their 2023 forecasts is for two hikes, up from zero in March. Interestingly, the forecast ranges for inflation (2.0-2.2%) and unemployment (3.2-3.8%) for 2023 are both unchanged. Taken together, it looks as if the FOMC is slightly less comfortable with waiting for full employment before lift-off.

Prices for 2023 eurodollar futures adjusted down following the press conference, and now more closely reflect this new interest rate forecast. Three month Libor currently sits within the policy rate range, but when the Fed starts raising rates money market rates will probably build in a positive spread. The risk remains asymmetric but following last week’s jump in yields the compelling risk/return on shorting has gone.

If the FOMC’s more hawkish rate outlook with an unchanged economic outlook means they’re embracing a modicum of humility, this is a positive development. It means the long overdue ending of the $120BN in monthly bond purchases is within sight.

Inflation is far from a purely US problem. Central banks in Russia, Turkey and Brazil have all raised rates in recent weeks. Norway’s central bank expects to raise rates by 1% over the next year. The UK is experiencing higher than expected inflation, and is engaged in a similar debate about how transitory it’s likely to be.

The irony is that the US is dropping most Covid restrictions earlier than almost any other country, has the most accommodative monetary and fiscal policy and the fastest GDP growth. Jay Powell referenced inflation 16 times in his prepared remarks and employment 15 times, a carefully calibrated balance that was probably no accident. He still sounded quite dovish, prioritizing getting everyone who wants a job into one over keeping inflation at 2%. He believes inflation expectations remain, “broadly consistent with our longer-run inflation goal of 2%.”

But the forecast of earlier tightening embedded in the dot plot shored up Powell’s message. Inflation expectations, which had modestly declined over the past month, fell another 4bps. On Friday, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis President James Bullard said inflation was stronger than anticipated. I suspect Fed chair Powell is more dovish than the median on the FOMC.

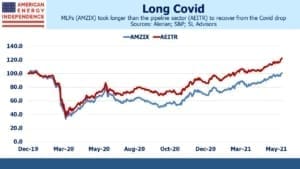

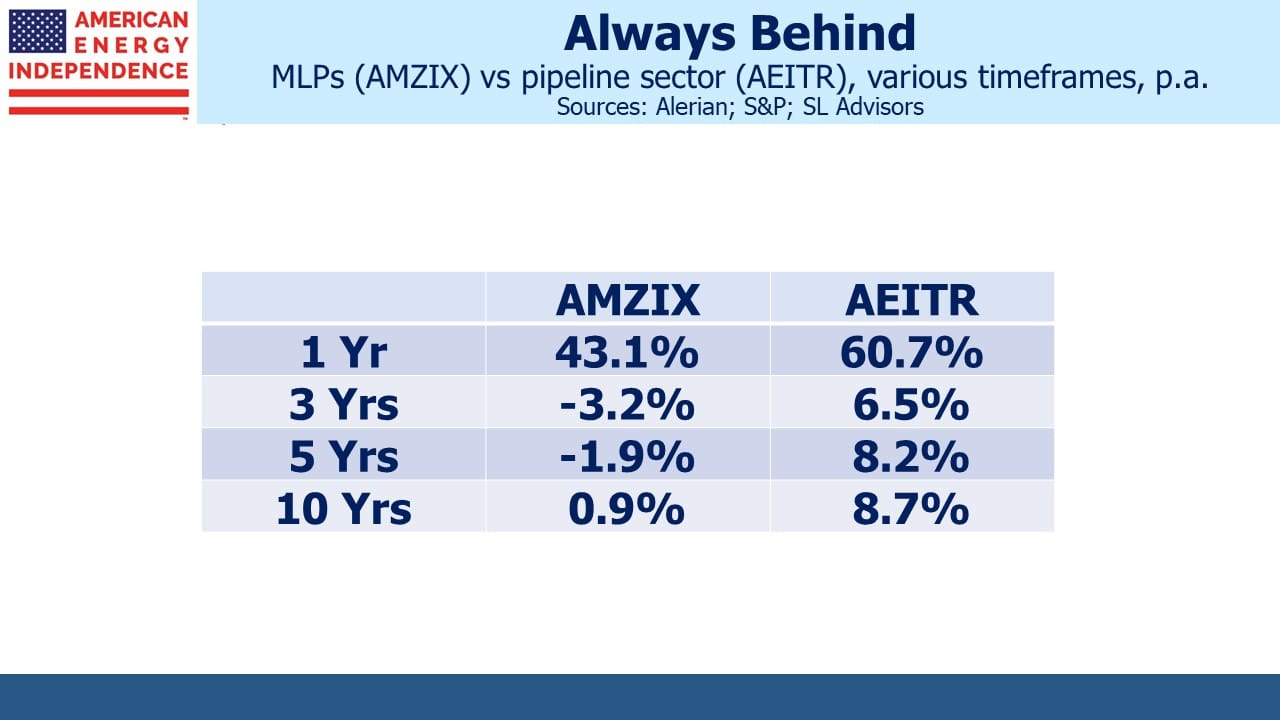

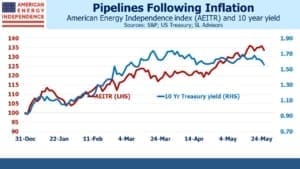

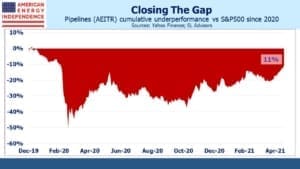

We’ve noticed that eurodollar futures and inflation-sensitive stocks such as the energy sector have developed a changed relationship. This year yields rose with commodities, pulling pipelines along with them. But the positive correlation between interest rates and energy is showing signs of evolving into a more complimentary relationship. Over the past month prior to Wednesday, pipeline stocks rallied strongly at the same time as eurodollar yields fell, reflecting declining expectations of 2023 tightening. Following Powell’s press conference eurodollar yields moved sharply higher. James Bullard gave them a further push on Friday. The market is adjusting to a slightly more hawkish Fed and consequently moderating inflation fears. Commodities and energy fell as a result.

The Fed’s posture of extreme monetary stimulus synchronized with profligate fiscal support raised inflation fears. A step back from that has moderated such concerns. It may be that rates and energy will adopt more of a yin and yang relationship, although in our view both are likely to be higher a year from now.

We are invested in all the components of the American Energy Independence Index via the ETF that seeks to track its performance.