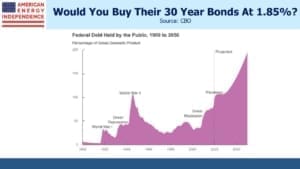

Modern Monetary Theory Goes Mainstream

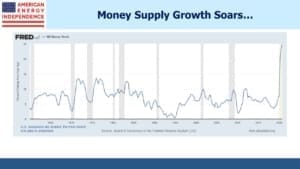

Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) argues that because a government can never go bankrupt in its own currency, the only constraint on spending is inflation. Applied to the U.S., this justifies pandemic stimulus checks, spending on infrastructure and clean energy initiatives, expanded Obamacare and doubtless other initiatives too. Price tabs begin at $1TN nowadays. Stephanie Kelton’s book, The Deficit Myth: Modern Monetary Theory and the Birth of the People’s Economy is worth reading to better understand where this theory will take us. We reviewed it last November.

There are no votes left in fiscal discipline, and investors don’t seem too worried either. With 30 year yields at 2%, there’s little evidence that voters should be more concerned than the bond market.

Kelton was an advisor to Bernie Sanders, now head of the Senate Budget Committee. We are embarked on MMT – although even Kelton’s advocacy of fiscal profligacy recognizes the inflationary constraints of the government outspending the economy’s ability to deliver goods and services. She quaintly believes Congress should score spending plans based on their potential to cause higher inflation, as if election cycles had ceased to exist. No such concern burdens Biden’s $1.9TN proposed Covid relief plan.

Betting on higher inflation, and rising rates, has been a losing proposition for over thirty years. It would seem foolish to expect anything different now – except that making such a bet is extraordinarily cheap.

The eurodollar curve, which reflects market expectations for three month Libor, is very flat. It’s true Fed chair Powell has said the Fed plans to keep rates low for a long time, and is willing to see inflation move above 2%, compensating for periods when it’s been stubbornly below their desired average. The futures curve takes him at his word.

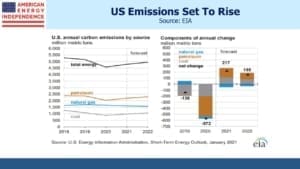

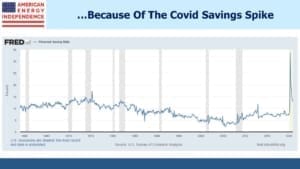

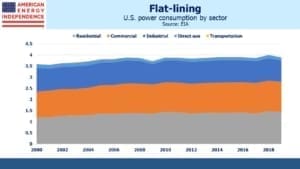

But the stage is set for the market to test this view. The kindling includes unprecedented fiscal stimulus, almost $5TN in money market funds, up $1TN in a year (some of which is entering the stock market via Robin Hood) and a probable burst of pent-up consumption once pandemic lockdowns are eased. This may all be easily absorbed by the economy – but many are watching carefully, and a couple of high CPI figures will confirm the worriers.

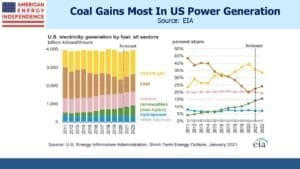

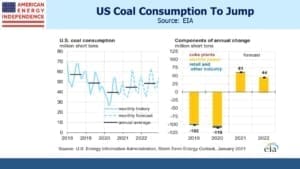

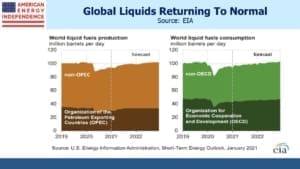

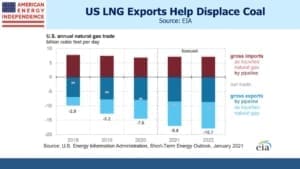

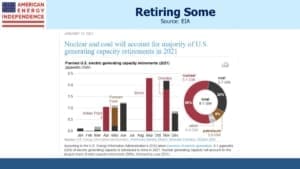

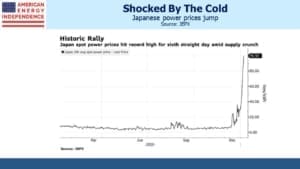

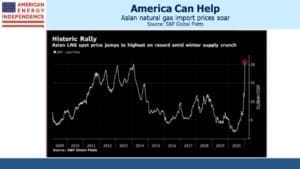

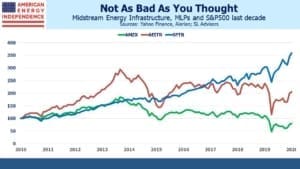

Commodity prices have been rising. Energy companies are more cautious with their investment plans, which is going to constrain supply in the future. Pipeline opponents have made new construction prohibitive. Investors in the sector like higher energy prices and lower growth capex, so are finding the Democrat agenda surprisingly appealing. These are encouraging circumstances for midstream energy infrastructure, up 11% so far this year.

Bond yields are slowly rising to reflect inflation risks, but remain uninvestably low. Sovereign debt ceased offering real returns (i.e. above inflation) years ago. Those days may never come back – MMT advocates will eagerly grasp this vindication of their policies.

December 2022 eurodollar futures yield 0.30%, just 0.10% above today’s three month Libor with 22 months to go and reflecting equanimity about the possibility of higher rates over that time frame. A short position will lose roughly half a basis point per month — this is the cost of negative carry. If the market develops even the slightest fear that rates may rise, a 25 or 50 bps move in eurodollar futures is likely. The Fed probably will remain on hold – but there’s little to be made betting with them, and little cost in betting against.

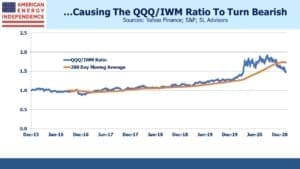

Stocks remain modestly attractive, but that is dependent on bond yields. Factset 2021 and 2022 earnings forecasts for the S&P500 are moving steadily higher, albeit still not back to pre-pandemic levels. But 2021 forecast S&P500 EPS of $173 per share is nonetheless $10 ahead of pre-pandemic 2019. Covid has changed millions of lifestyles for the better and created big winners and losers among businesses, but history will show a one year dip in public company profits.

Energy companies dominate the list of 1Q21 upward revisions to earnings. The Equity Risk Premium (ERP), the difference between the S&P500 earnings yield and ten year treasuries, is supportive. However, if long term interest rates were to rise, say, 1% stocks would be less alluring.

The goal of MMT is to push the edge of the envelope. Both political parties have discovered that increased deficits carry no penalty. Now that we’ve informally adopted MMT, higher inflation one day is assured. We just don’t know when. But Federal government spending policies reflect an enthusiastic pursuit.

We are invested in all the components of the American Energy Independence Index via the ETF that seeks to track its performance.