The Blogs You Liked, Part 2

Although we generally write about investing in midstream energy infrastructure, we find macro subjects interest our readers too. In April, not long after the market low, The Stock Market’s Heartless Optimism was popular, as any guide to the market’s direction was eagerly sought. We regularly use the Equity Risk Premium (ERP) to illustrate the relative value of stocks versus bonds. Earnings forecasts never fell as far as the market, which is what propelled its rebound for the remainder of the year.

Full year S&P500 EPS is currently forecast by Factset to come in at around $140 once 4Q20 reports are out. For 2021, analysts are forecasting S&P500 EPS of $170. The 21% increase looks impressive, but a year ago the 2021 EPS forecast was $197. Despite this 14% drop in forecast earnings, the market returned 18%. It’s been cheaper. Lower bond yields helped, but relative value has clearly deteriorated. At 3.6, the 2021 ERP shows stocks are attractive compared with the past 50 years, but mid-range for the past decade.

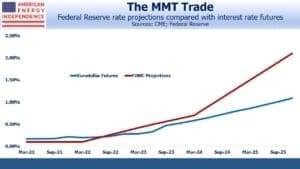

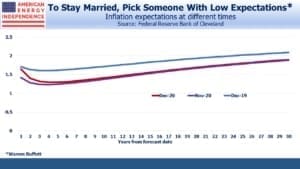

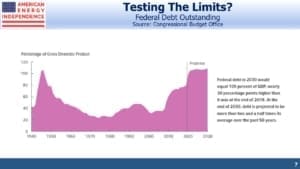

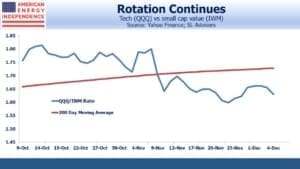

A 1% jump in bond yields would likely expose the market’s lofty valuation. This has been true for years without result. Investors need to consider the possibility of such, improbable though it seems. Recent M2 money supply growth of 26% has eclipsed the inflationary ‘70s and ‘80s. Taming the deficit is a quaint hobby with few votes, and the Fed wants to see inflation above its 2% target for a period of time before acting. This doesn’t mean inflation is about to jump, but the mismatch between investor positioning and the odds of such a surprise appears significant.

We wrote on this topic recently (see A Cheap Bet On Inflation), drawing a good number of emailed comments. One friend and client generously described it as “post of the year”.

Inevitably, we wrote on Covid, as reasonably numerate non-medical people trying to figure it out. Opinions are strong on both sides, and the most reasoned responses came from those who believed we were underestimating the threat. Our morning meetings often include a discussion, and there isn’t complete agreement even within SL Advisors on certain elements. What is unarguable is that life won’t return to normal until people feel safe, regardless of whether they’re over-estimating their risk or not.

For my part, in New Jersey in March and April of last year we endured a loss of personal liberty I never thought possible in America. Even a solitary walk in the woods was banned. As soon as we could, my wife and I escaped for a trip south, where infections were lower and society more open. This was briefly chronicled in Having a Better Pandemic in Charleston, SC, which many enjoyed.

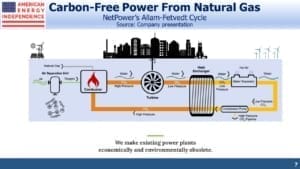

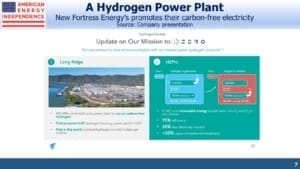

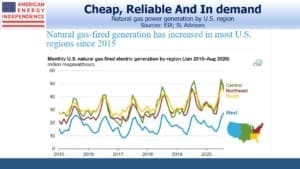

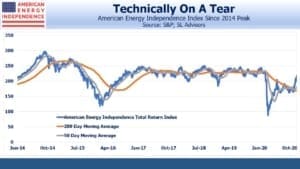

Climate change will continue to be a dominant driver of energy sector returns. Anything linked to the energy transition draws fund flows (see Hydrogen Lifts an LNG Company).

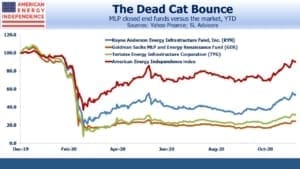

Valuations defy fossil fuels’ 80% share of global energy, and the relentless growth in developing countries’ consumption to support rising living standards. We have long thought natural gas a better bet than crude oil. 2020 highlighted the former’s resilience as the collapse in transportation demand was mostly felt in oil markets (see With Energy Uncertainty, Natural Gas Offers Stability and Natural Gas Demand Still Stable).

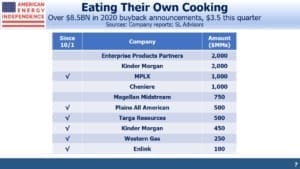

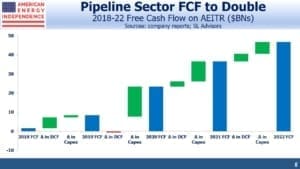

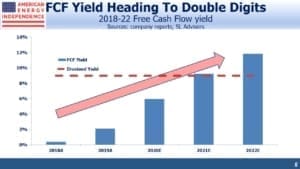

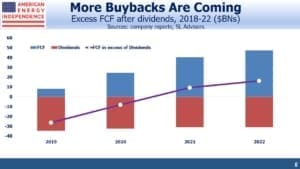

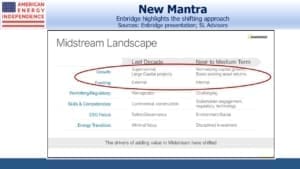

The election result means energy companies will continue cutting growth spending, a welcome development. Next week’s Georgia runoffs for the Senate will determine whether Goldilocks Gridlock or a razor-thin Democrat majority prevail. The former is better, but pipeline free cash flow is growing in either scenario. Why Exxon Mobil Investors Might Like Biden explained how we thought politics would affect the sector.

Our podcasts have developed a growing listener base too. Among the most popular were Joe Biden and Energy, Climate Change Was Never Our Biggest Threat, Exxon’s Bet Against Renewables and Democrats Mean Higher Energy Prices.

As always, we invite your feedback whether positive or negative. We aim to produce what you want to read or listen to.

We are invested in all the components of the American Energy Independence Index via the ETF that seeks to track its performance.