G20 Confronts Environmental Reality

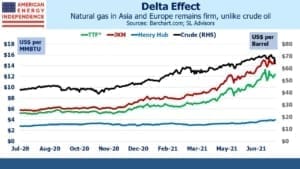

Last week’s meeting of G20 environment ministers to discuss global warming exposed fault lines in the rich world/poor world debate about climate change. Most notably, they couldn’t agree to phase out coal, even though this is the most effective step nations could take to reduce emissions of Global Greenhouse Gases (GHGs). Coal burning power plants can be replaced with natural gas. The US has done this successfully for over a decade, although progress has stalled this year due to higher natural gas prices.

China draws accolades for its huge investments in solar and wind. Last year they reportedly added 120GW of solar and wind power, although analysts were skeptical about the about the figure’s veracity. China has adopted a goal of being carbon neutral by 2060, so you would think that phasing out coal would be consistent with this goal.

But China’s refusal to make such a commitment reveals their other climate commitments to be less than solid. From the origins of the Covid pandemic to supporting cyberattacks, the Chinese government provides plenty of reasons for their public statements to be disbelieved.

The pie chart shows the magnitude of the problem. China burns half the world’s coal. The challenge of global warming pits the desire of OECD countries to limit emissions against the drive for higher living standards in the developing world. These two objectives are in conflict, as the G20 meeting showed.

The irony is that rich countries are far better equipped to protect themselves from the consequences should they occur, such as rising sea levels and more extreme weather, than poorer ones. In effect, America’s climate czar John Kerry is telling the developing world, let us help you by all reducing emissions since the results will be worse for you than for us. Those potential beneficiaries are responding that raising living standards for their populations, which requires increased energy consumption, is more important.

Seven years ago, John Kerry in a speech in Jakarta exhorted Indonesians to, “Make a transition towards clean energy the only plan that you are willing to accept.” At the time, an estimated 36 million Indonesians didn’t have access to clean water (see The Moral Case For Fossil Fuels). They have different priorities, appropriately so.

It’s positive that these opposing views are being brought into the open, because it makes eventual progress more likely. John Kerry’s view is hopefully less condescending than it was back then, having confronted reality.

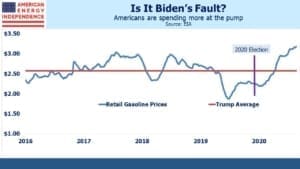

India published a dissenting statement alongside the official communique, urging countries to reduce per capita emissions down to the global average. This is where political support quickly evaporates. For the US, this would require a 70% cut in GHGs, and therefore energy use. Joe Biden understands Americans have little tolerance for constrained access to energy. The White House recently lobbied OPEC to raise production so as to slow the increase in gasoline prices, even though higher prices are both necessary to reduce emissions and a consequence of his administration’s policies.

The White House has stopped short of seeking to phase out coal in the US, although it has a plan to “Invest in Coal and Power Plant Community Economic Revitalization” which aims to support areas “hard-hit by past coal mine and plant closures and vulnerable to more closures” (italics added). Phasing out coal in the US would be more easily done as part of a global consensus to do so which was sadly absent.

OECD countries are reducing emissions, but the world overall is not, other than through last year’s Covid recession. Climate extremists would have us shift to intermittent renewables even while the world’s biggest emitter, China, continues to add coal burning power plants at a dizzying pace. China’s planned coal plant additions outnumber the entire US fleet. They’ll more than offset any progress we make in this country. The G20 conference just concluded did at least expose the conflicting goals.

We are invested in all the components of the American Energy Independence Index via the ETF that seeks to track its performance.