Why The Energy Crisis Will Force More Realism

The two front covers from The Economist, thirteen months apart, represent an overdue liberal education. Much of the mainstream press has heralded the energy transition to renewables as a source of jobs, innovation and everything else good including lower CO2 emissions. In September 2020 The Economist ran a leader titled Is it the end of the oil age? They excitedly continued, “As covid-19 struck the global economy earlier this year, demand for oil dropped by more than a fifth and prices collapsed. Since then there has been a jittery recovery, but a return to the old world is unlikely. Fossil-fuel producers are being forced to confront their vulnerabilities.”

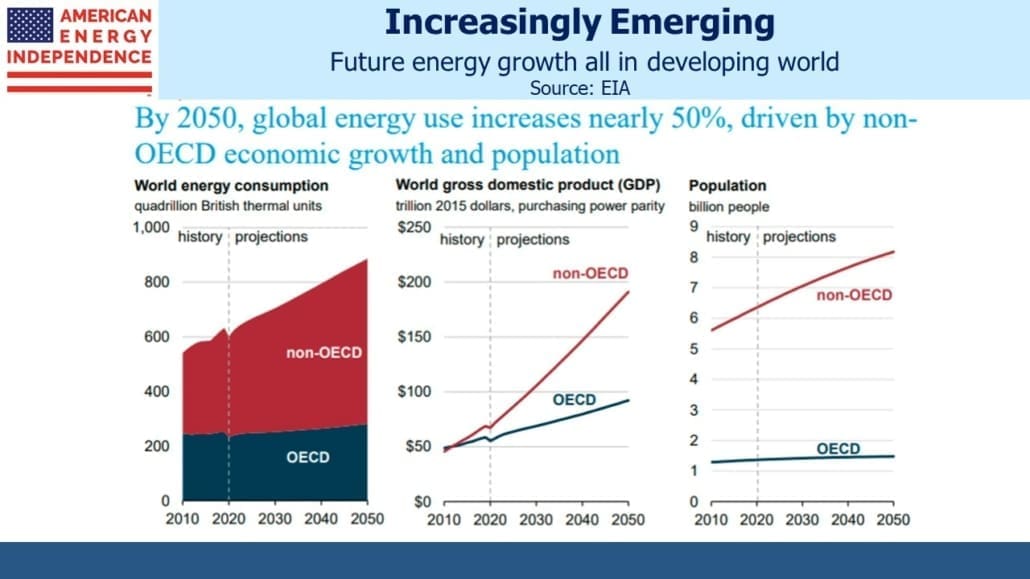

Today, the US Energy Information Administration (EIA) expects total liquids demand to be 36% higher by 2050. OPEC expects crude oil demand in 2045 to be 108 million barrels per day, versus around 100 currently. In covering the energy crisis engulfing most of the world, The Economist now warns, “the first big energy scare of the green era is unfolding.”

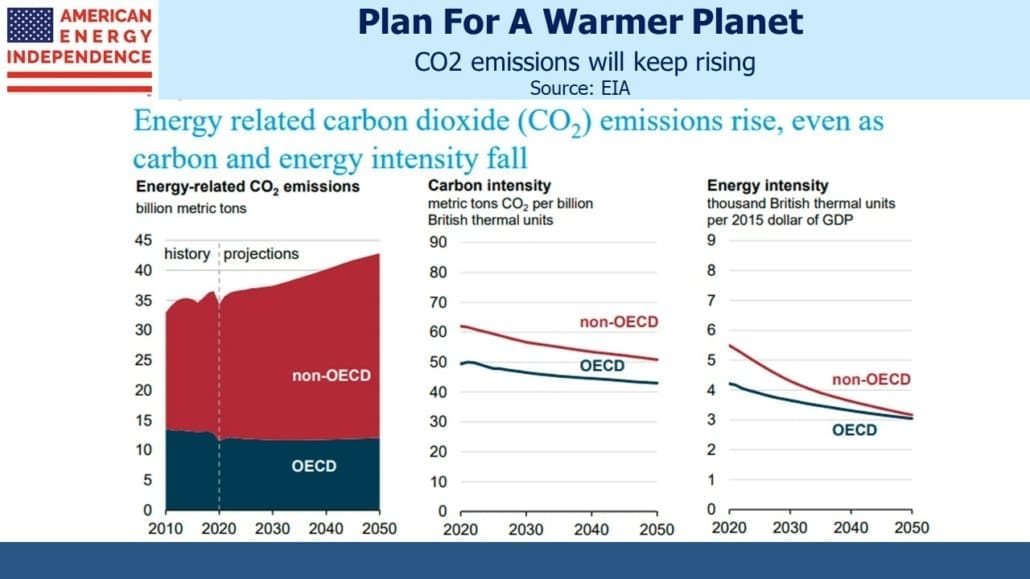

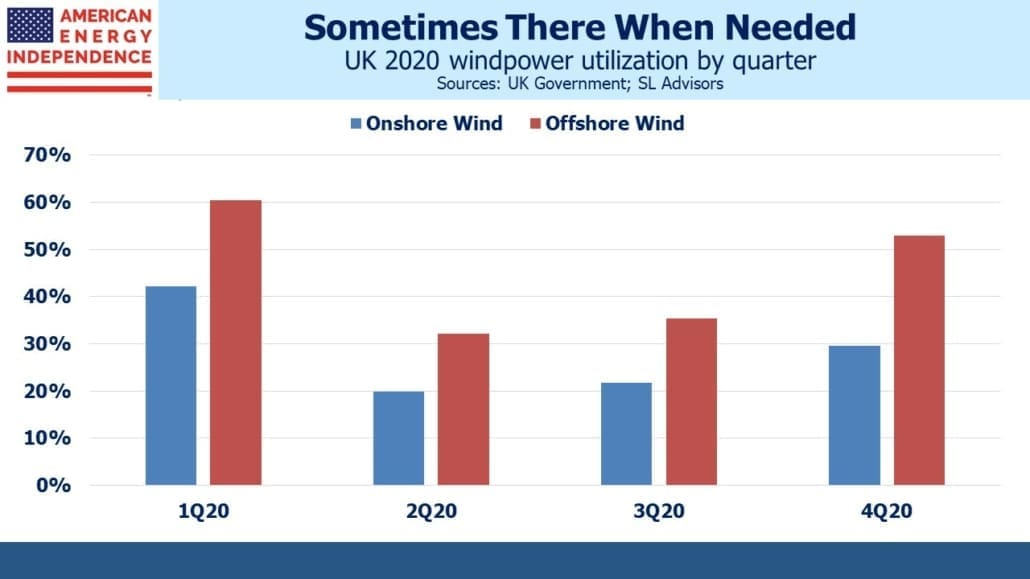

It shouldn’t have been hard to see coming. Climate extremists have disingenuously promoted solar and wind as the only acceptable sources of electricity. They have glossed over intermittency and the reliance of weather-dependent energy on back-up (usually natural gas or coal) to make it work. They’ve ignored that electricity provides only 17% of the world’s energy, assuming that the other 83% could be electrified and all supplied by renewables.

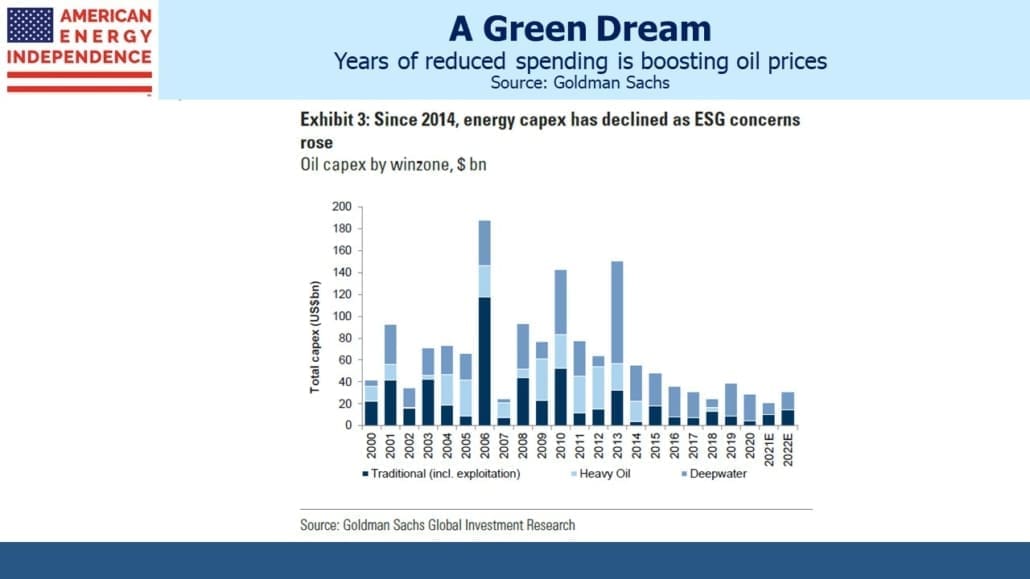

Oil and gas production has been demonized to such an extent that public companies have pulled back from making new investments, causing today’s rising prices. Over 80% of the world’s energy comes from fossil fuels. Vaclav Smil, a prolific multi-disciplinary writer, has explained in detail why energy transitions take decades to play out, and why this one will be no different.

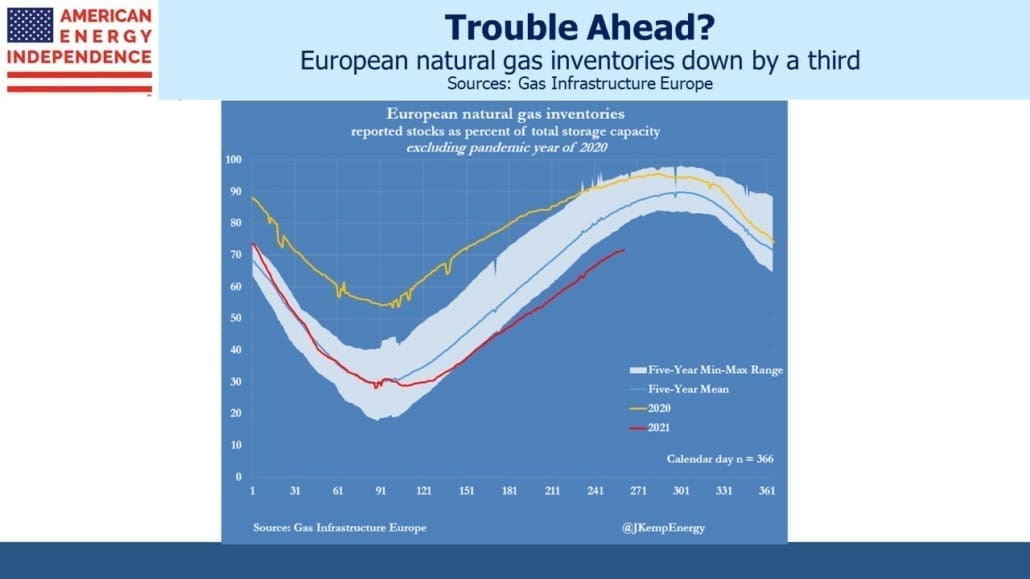

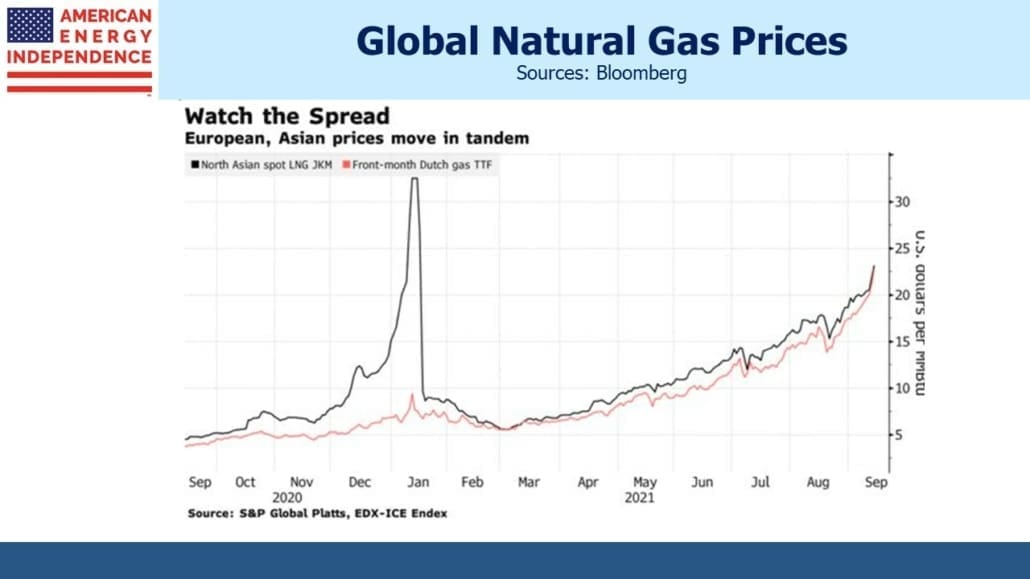

Finally, political leaders have been keen to demonstrate their green credentials by using every opportunity to curb new production of oil and gas, but hypocritically reluctant to welcome the higher oil and gas prices that result. Energy systems will shift mostly based on economic signals. With Europe and Asia paying 3-5X more for imports of liquified natural gas than a year ago from Qatar, Australia and the US, liberal politicians could claim that their policies are working. Instead, European leaders are pleading with Russia to dispatch more natural gas. President Biden wants OPEC to increase oil production even while he promotes policies to curtail domestic production.

With inconvenient timing, the COP26 climate change conference will be held next month in the UK, where coal plants have been restarted to compensate for a windless North Sea and prior policy decisions that slashed the UK’s natural gas storage capacity. Although energy prices are rising, nobody is bidding up solar panels or windmills.

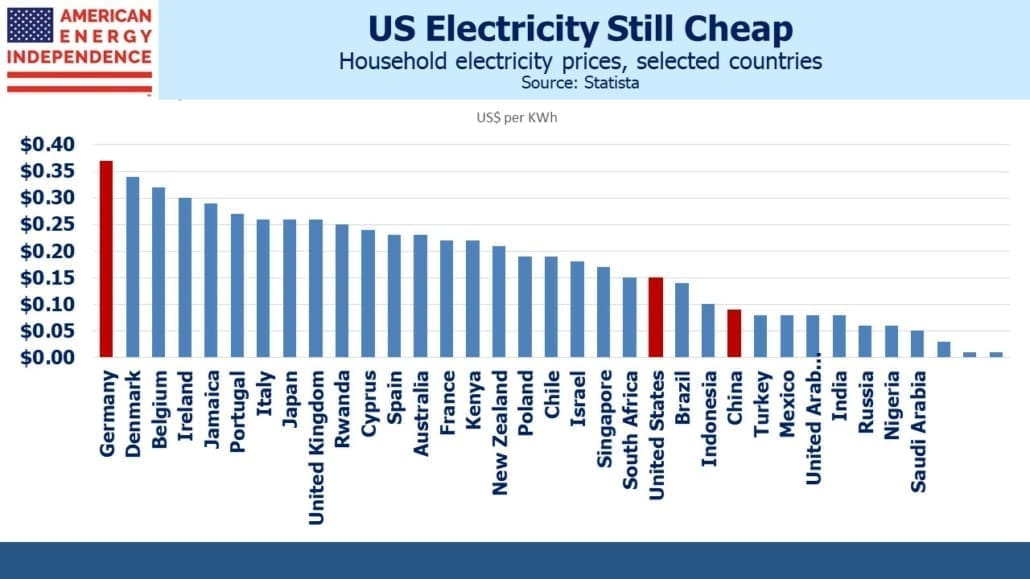

We’ve been writing about the unrealistically narrow focus of climate policies for several years. Emerging economies want higher living standards, which mean increased energy consumption, more than they want to reduce CO2 levels. Climate extremists oppose everything that works even including nuclear. Advocates claim that solar and wind are the cheapest form of power, implying that utilities are stubbornly retaining legacy energy systems and foregoing higher profits in the process.

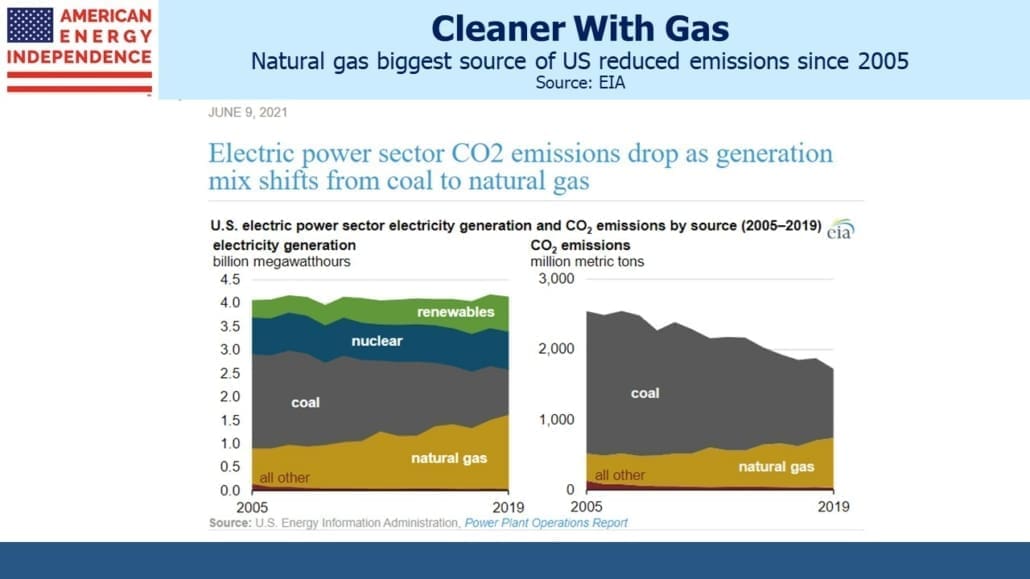

The juxtaposition of the two Economist front covers represents the start of a more realistic debate over the energy transition. Now their editors recognize that “the mix must shift from coal and oil to gas which has less than half the emissions of coal.” A year ago, The Economist argued that solar and wind could reach 50% of global power generation by 2050. Last week, the EIA’s International Energy Outlook 2021 predicted a more sober 40% share. Even that figure relies on robust 8.7% and 4.7% annual growth for solar and wind respectively over the next three decades. Today’s chastened Economist editors now concede that, “More nuclear plants, the capture and storage of carbon dioxide, or both, are vital to supply a baseload of clean, reliable power.” A year ago they mentioned neither.

Most people who give the issue much thought favor reduced CO2 emissions. But political discourse has been simplistic, which has led to bad policy. Germany and California are leaders in renewable power. Their residents pay the world’s highest electricity prices and in the Golden state suffer third world reliability. Sales of diesel-powered generators have risen 22% in California in the past year, as residents seek protection from their unreliable grid. Nobody should want to emulate their model. Meanwhile China goes on burning half the world’s coal and producing 28% of emissions, content to sell OECD countries the solar panels and windmills they crave.

Transitioning to an energy system that generates less CO2 will be very expensive – if it’s worth doing, it’s worth the cost. Policymakers should be honest with voters and explain why concern about climate change means accepting higher energy prices. We should be using more nuclear; switching from coal to gas; using carbon capture; introducing hydrogen; and including solar and wind only to the point where relying on their opportunistic supply model doesn’t destabilize power markets.

An example of new technology is Air Products, which is building a “blue hydrogen” plant that will produce 750 million cubic feet per day. For reference, the US produces around 90 billion cubic feet per day of natural gas. The new facility will use natural gas as feedstock, and sequester the resulting CO2 underground.

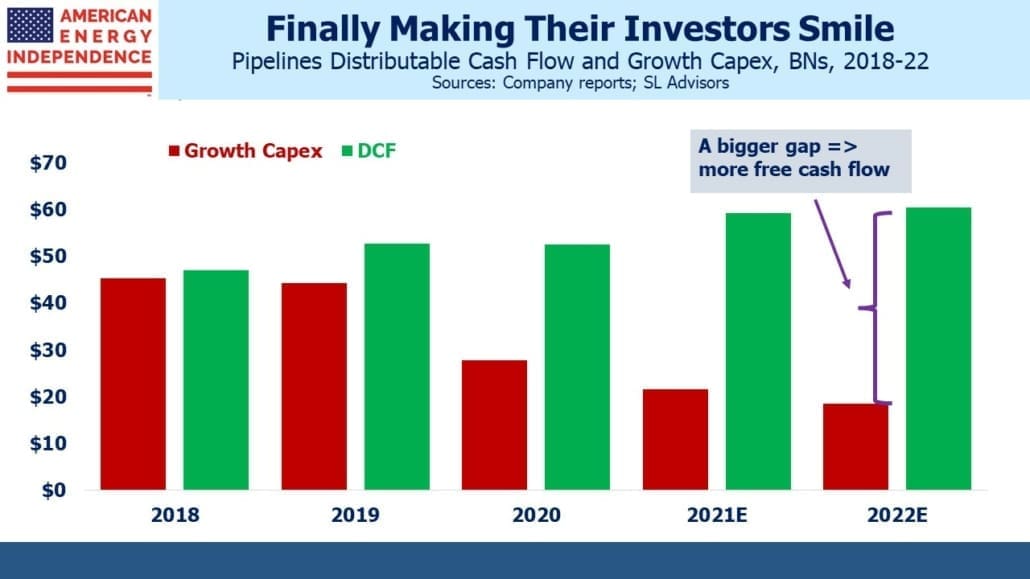

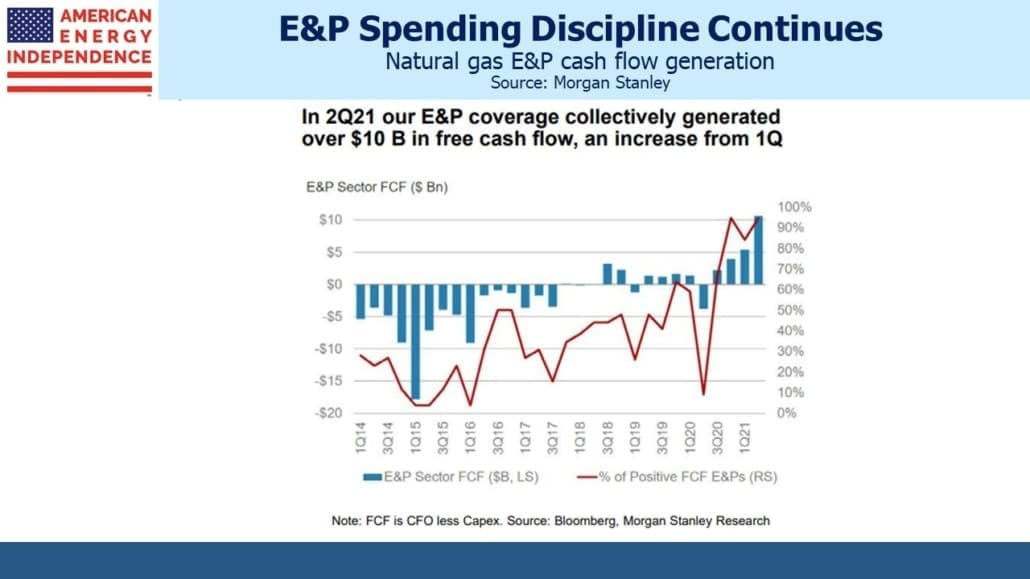

Hydrogen is expensive to produce, so initiatives like this need higher energy prices in order to compete. Democrat policies are helping do just that, even if their political leaders won’t take the credit. For energy investors, the unfolding energy crisis is great news. As public policy becomes more realistic, the outlook for natural gas and US midstream infrastructure keeps improving.

We have three funds that seek to profit from this environment:

Energy Mutual Fund Energy ETF Real Assets Fund