Situations We’re Following

The Mountain Valley Pipeline (MVP) has suffered countless delays because of continued legal challenges from environmental extremists. Permits issued by Federal agencies were on many occasions rescinded by judges. No infrastructure of any kind can be built with such a process. When the recently passed debt ceiling legislation deemed completing MVP “in the national interest” it implicitly acknowledged that the permitting process is broken. This overrode the prior legal judgments. Let’s hope this provides impetus for reform.

Equitrans (ETRN), whose frustrated efforts to complete MVP led to its extraordinary approval by legislation, has gained over 50% as a result. The stock had previously included no value for MVP, priced as if it would never be completed. NextEra, a partner in MVP, wrote its carrying value down to zero last year.

But ETRN remains well short of fully reflecting MVP’s value. Morgan Stanley has estimated a $14 sum-of-the-parts price target for ETRN. RBC has a Base Case of $10 and an Upside Case of $14. It’s currently at $9.50. The threat of further legal challenges remains. The legislation removed the jurisdiction of any court over actions by Federal agencies on this matter. But it allowed any claim against the law’s validity to be heard by the DC District US Court of Appeals. Analysts believe it’s highly unlikely any further legal challenges can disrupt MVP’s completion.

We think ETRN remains attractively priced.

Another situation we’ve been following is NextDecade (NEXT), whose planned Rio Grande LNG export project will be located on the northern shore of the Brownsville Ship Channel in Texas, with easy access to the Gulf of Mexico. By combining carbon capture with the condensing of natural gas that’s loaded onto LNG tankers, NEXT says it will be the only such US facility offering CO2 emissions reduction of more than 90 percent.

In April FERC re-approved the construction of Rio Grande. The next step is for NEXT to approve a Final Investment Decision (FID) so that construction can move ahead. CEO Matthew Schatzman expects FID to come before the end of this month.

Substantial uncertainty remains over how it will be financed. We estimate that building three trains with 2.3 Billion Cubic feet per Day (BCF/D) will generate $1.8BN in revenues and around $450MM in income to NEXT annually beginning by 2028. This is an $11-12BN project for a company whose market cap is below $1BN.

NEXT valuation estimates have a wide range. So any estimate of NEXT depends heavily on the mix of debt, preferred and common equity that’s used for financing. The FID announcement should provide enough detail about how Rio Grande LNG will be financed to provide sufficient cash flow visibility that its perceived risk will fall.

We think at current levels it offers an attractive return potential.

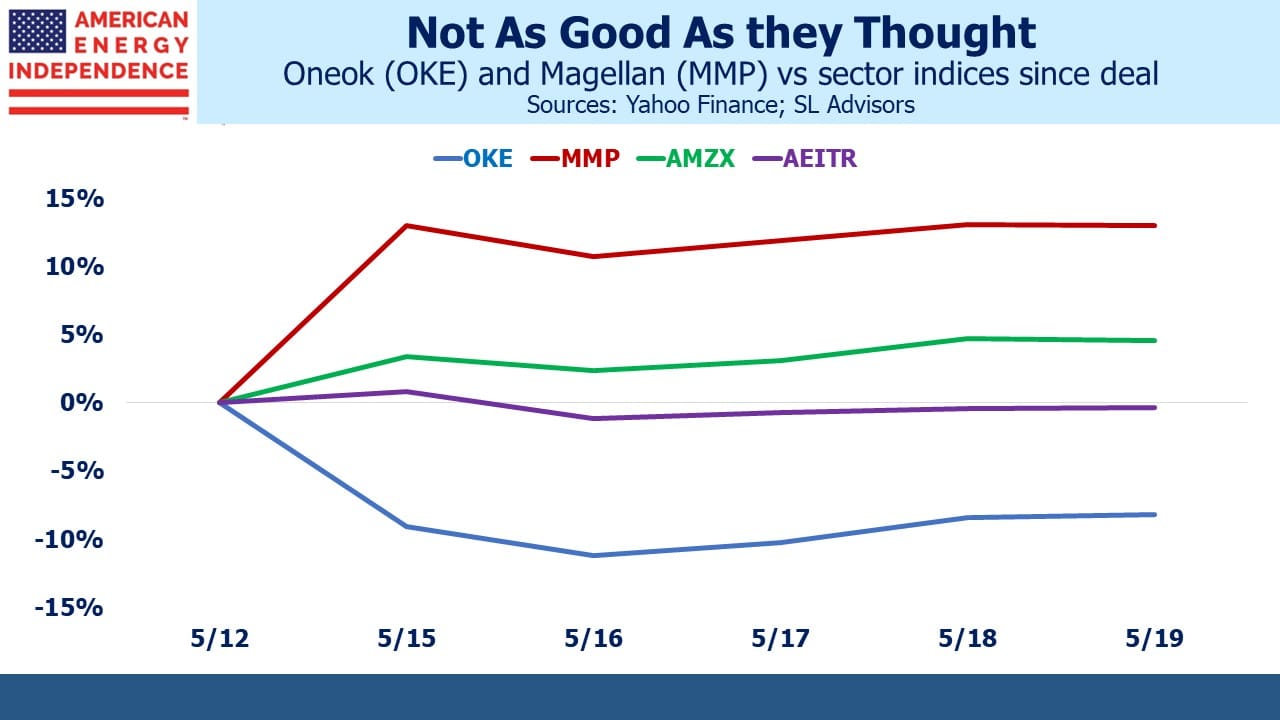

The proposed combination of Oneok (OKE) and Magellan Midstream has dominated our recent blog posts. We won’t relist our reasons for being opposed as we’ve covered them extensively (see Oneok Does A Deal Nobody Needs).

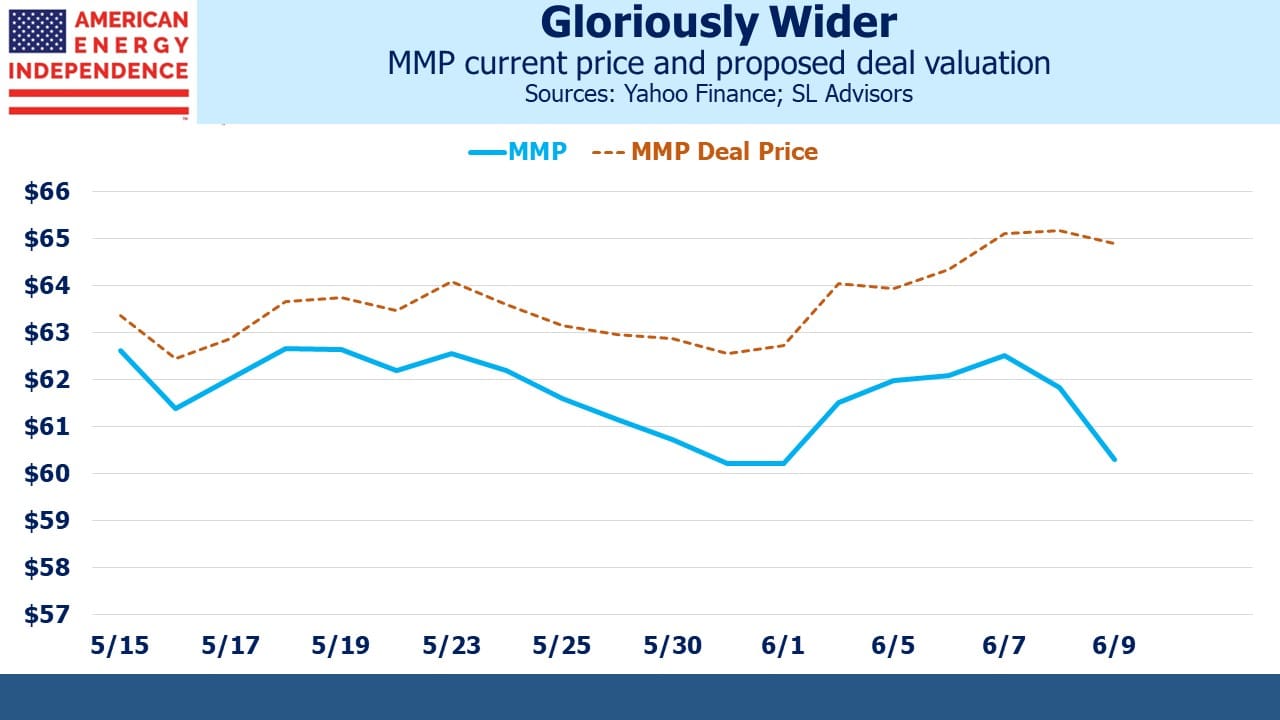

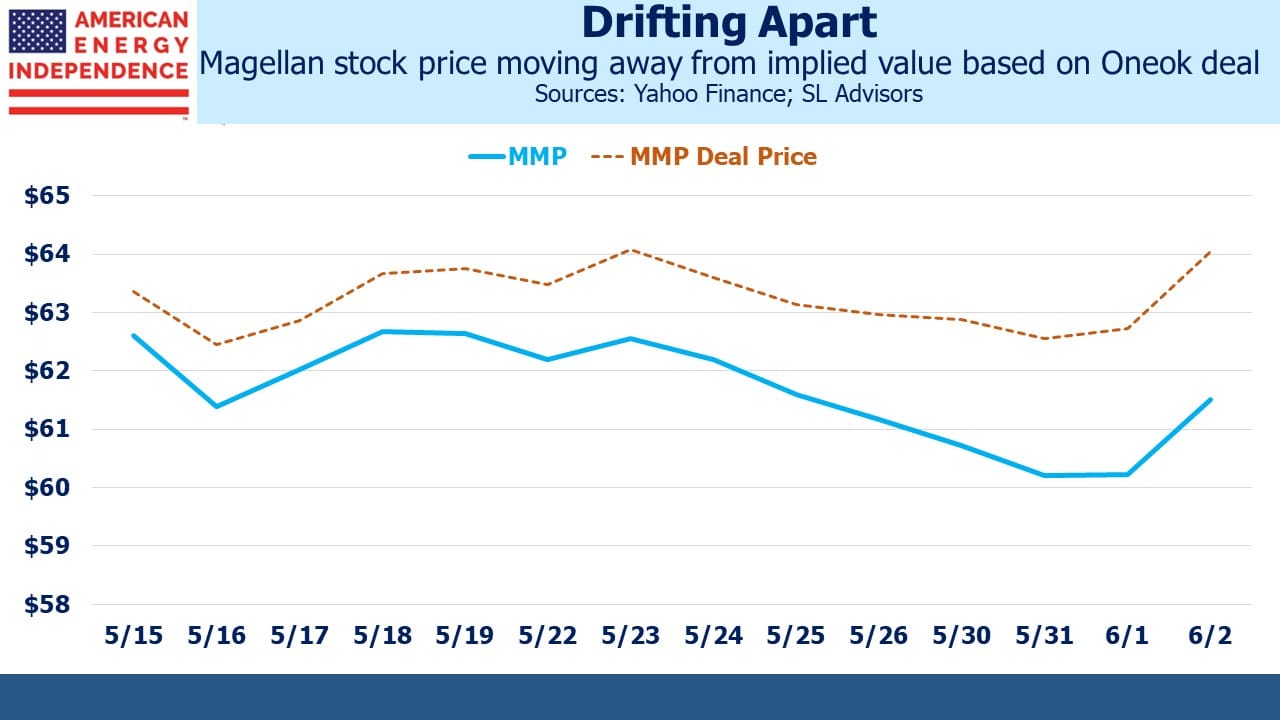

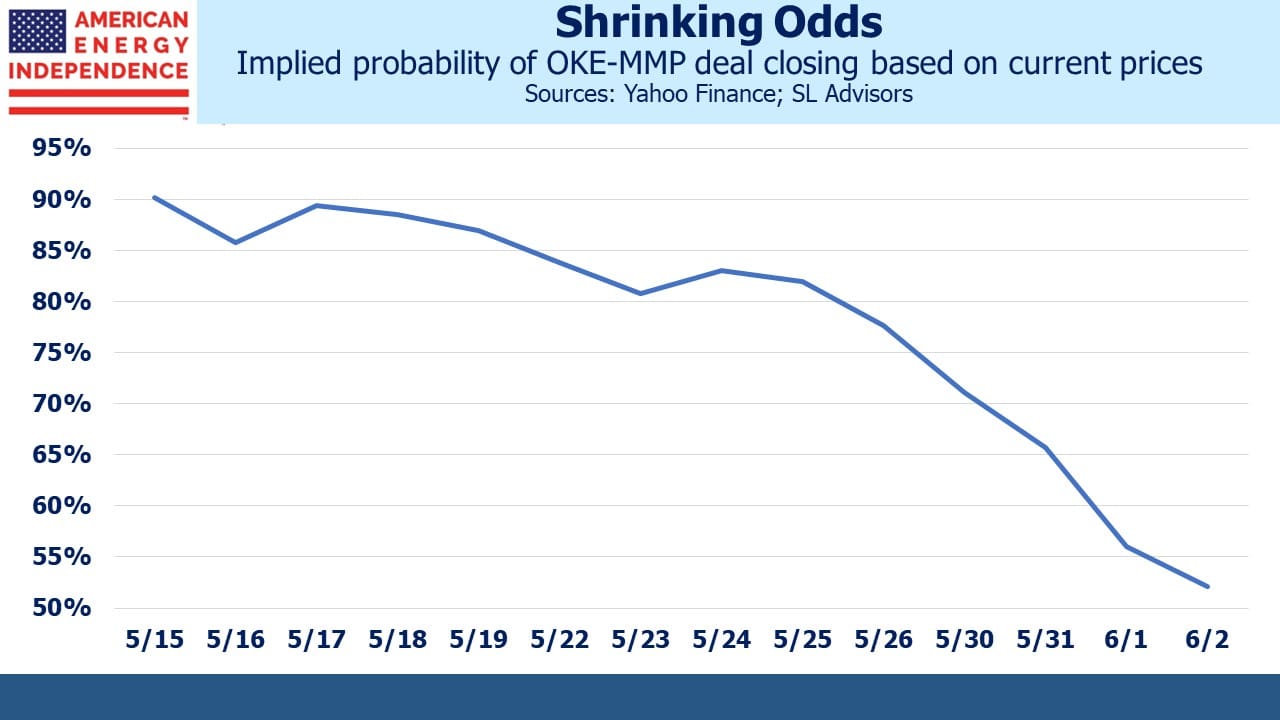

The market-implied probability of the transaction closing has dropped steadily since it was announced on May 15, because the gap between MMP’s current and proposed price is widening. Jim Murchie of Energy Income Partners recently wrote an open letter to MMP where he voiced criticisms similar to ours in objecting to the deal. Investor mood is turning against. Both companies will need to address the market’s cold response to their work.

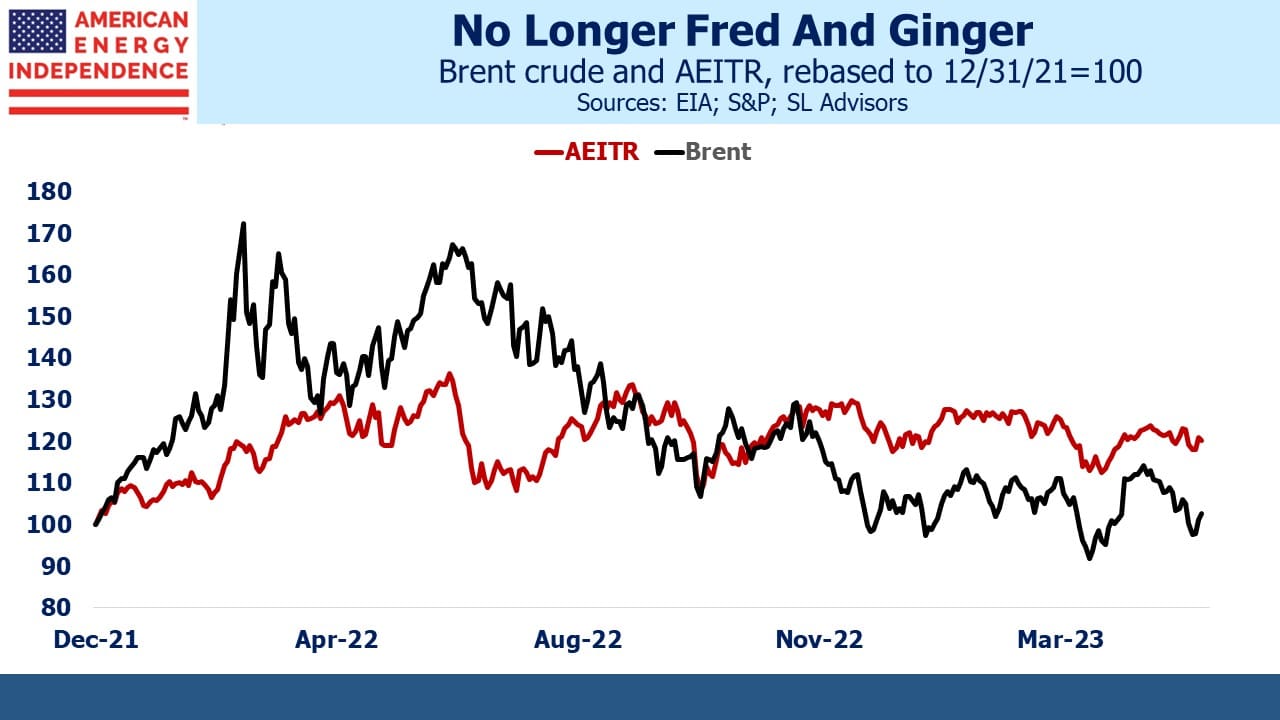

In recent conversations with investors, several have expressed surprise that the midstream sector isn’t performing better. Equity market leadership is incredibly narrow (see AI And The Pipeline Sector) so unless you own the half dozen or so stocks benefitting from the AI frenzy it’s hard to keep up.

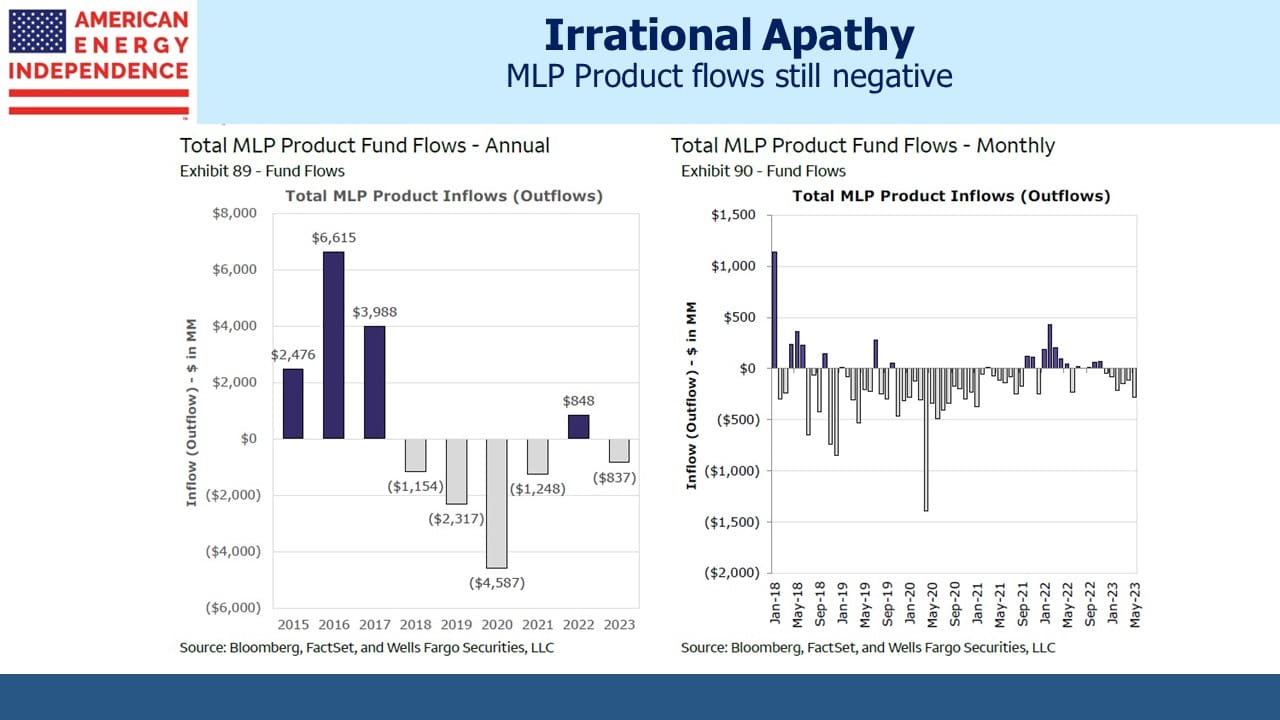

But fund flows into MLP Products, which is a decent proxy for mutual funds and ETFs in midstream energy infrastructure, have been negative every month this year. Last year’s inflow followed four negative years.

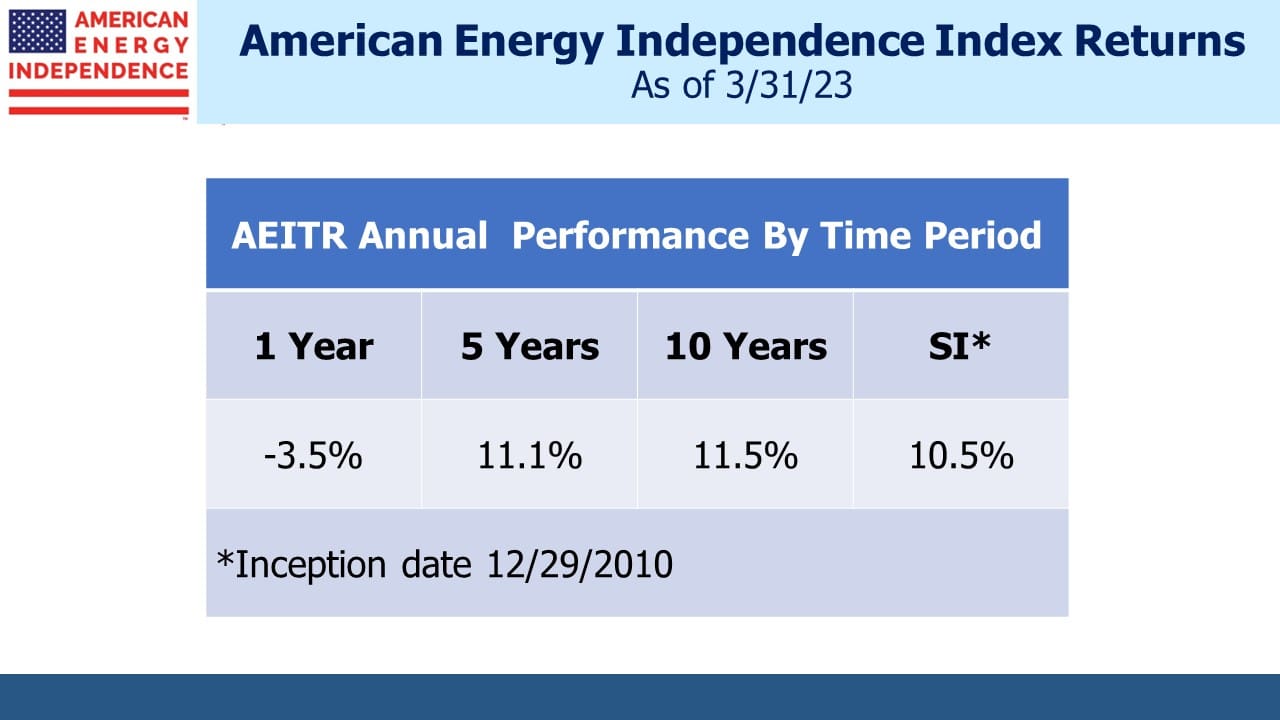

1Q23 earnings were good. Capex remains low, helped by opposition to new projects (hug a climate extremist and drive them to their next protest). Dividends are growing by our estimation 2-4%, and buybacks are retiring 2-3% of the sector’s market cap annually. Together with 6%+ yields, this provides the basis for annual returns of 10% or more.

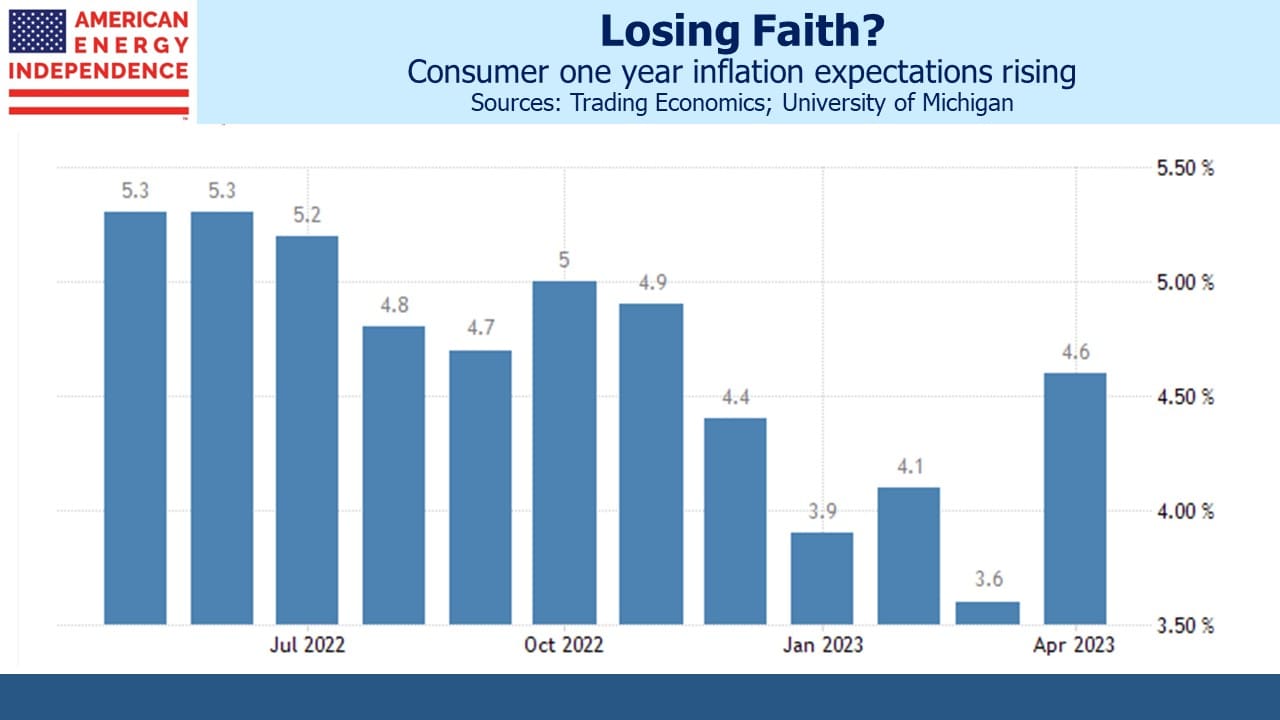

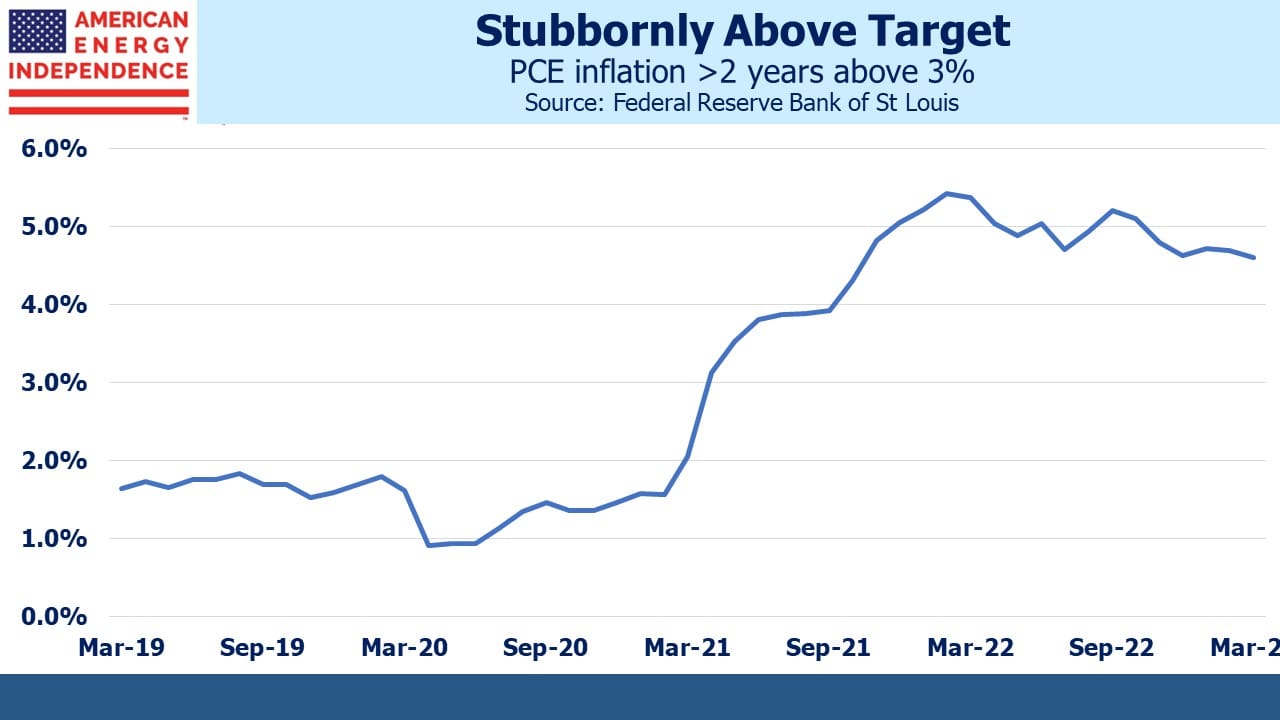

Clearly there’s no irrational exuberance causing investors to throw money at the pipeline sector. Irrational apathy might be more accurate. But the $837MM of net outflows through the first five months of this year is more than offset by the rate at which companies are buying back stock. There’s also the explicit link to inflation in that many pipeline contracts, representing up to half the sector’s EBITDA according to research from Wells Fargo, reprice using either PPI or CPI.

Eventually these persistently strong fundamentals will cause inflows to resume, as they did last year.

We have three funds that seek to profit from this environment:

Energy Mutual Fund Energy ETF Real Assets Fund