Gulf Tensions Back in Play

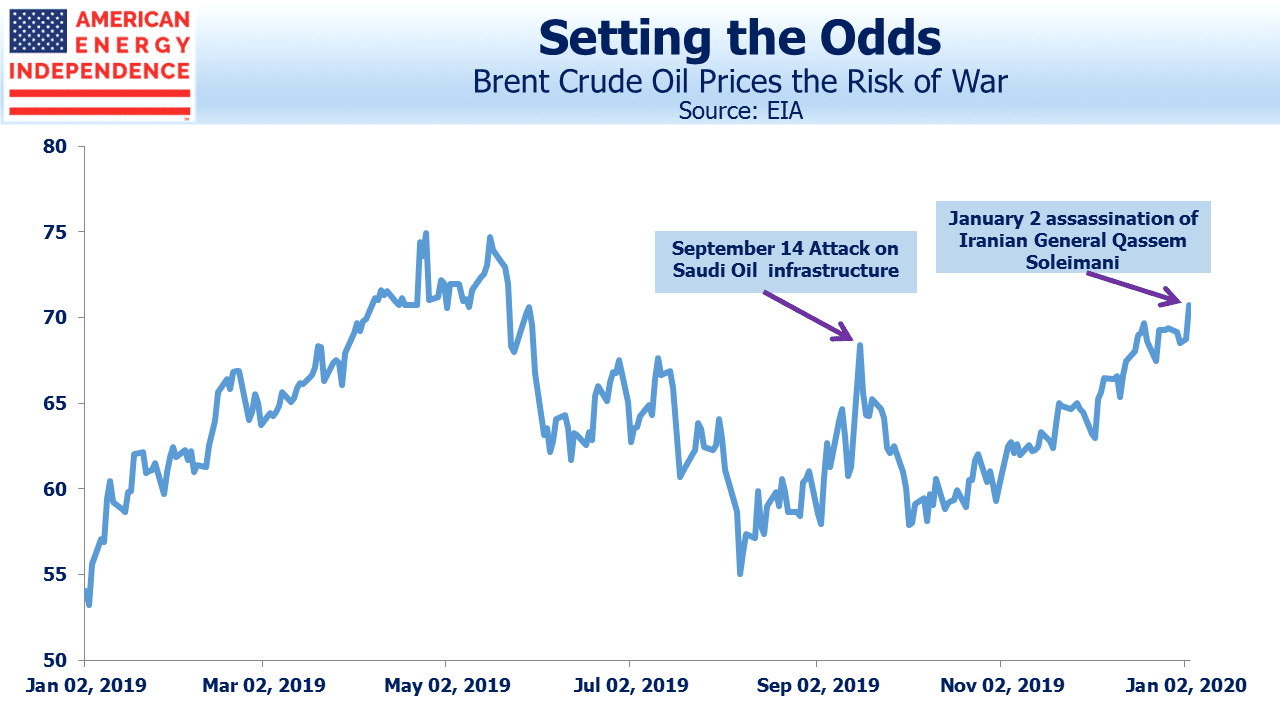

Just over three months ago, Saudi Arabian oil facilities were put out of action by a drone and missile strike. Oil prices jumped. It seemed indisputable than Iran was behind the attack – the sophistication was beyond that believed available to the Yemeni Houthi rebels who claimed responsibility. Saudi retaliation appeared inevitable, as half their oil production was taken offline.

Crude jumped, but the Saudis chose to ignore Iran’s provocation. Prices soon fell back as the market resumed its sanguine view of supply disruption.

So is it different this time? The assassination of Iran’s top military leader, General Qassem Soleimani, looks like a sharp escalation of tensions. Secretary of State Mike Pompeo justified it as preventing “an imminent” attack on U.S. citizens. Reportedly, both Presidents Bush Jr and Obama declined opportunities to kill Soleimani in the past, because they feared it would lead to war. Iran has so far pursued asymmetry, avoiding a hopeless direct military confrontation in favor of indirect responses under cover of plausible deniability. Will that strategy change?

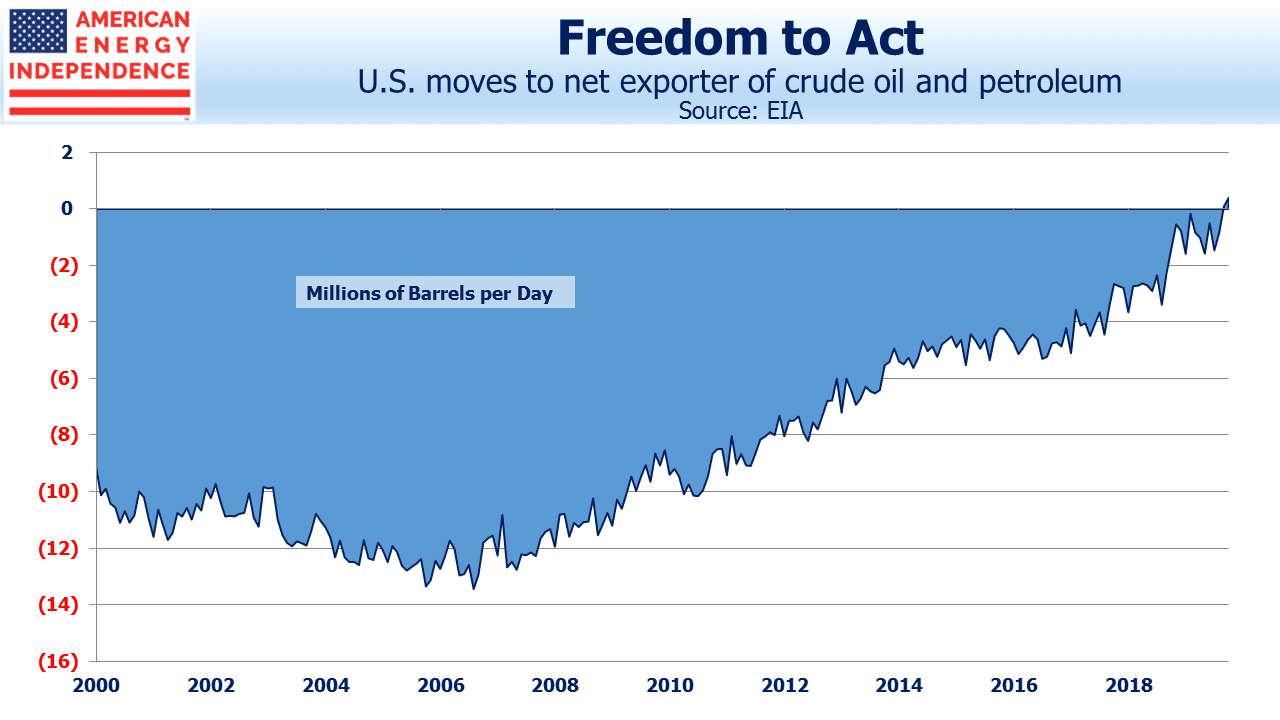

The Shale Revolution affords the U.S. far more foreign policy flexibility, now that OPEC can’t cause lines of cars at gas stations. Substantially higher domestic production of hydrocarbons made America a net exporter of crude oil and petroleum products late last year. Qassem Soleimani might be alive today if not for fracking.

Near term bets on crude oil or the energy sector will turn on how events play out, and it’s easy to have misplaced conviction with so many possible scenarios. Exxon Mobil (XOM) operates in 38 countries. Some of their infrastructure, which includes three JVs in Saudi Arabia, may be vulnerable, Geopolitical risk comes with complexity.

This is not the case for U.S. midstream energy infrastructure. For this sector, “international” is limited to Canada and in some cases Mexico. Pipelines are hard to damage because they’re underground, and while aboveground facilities are certainly more vulnerable, America is not an easy place for terrorist operations.

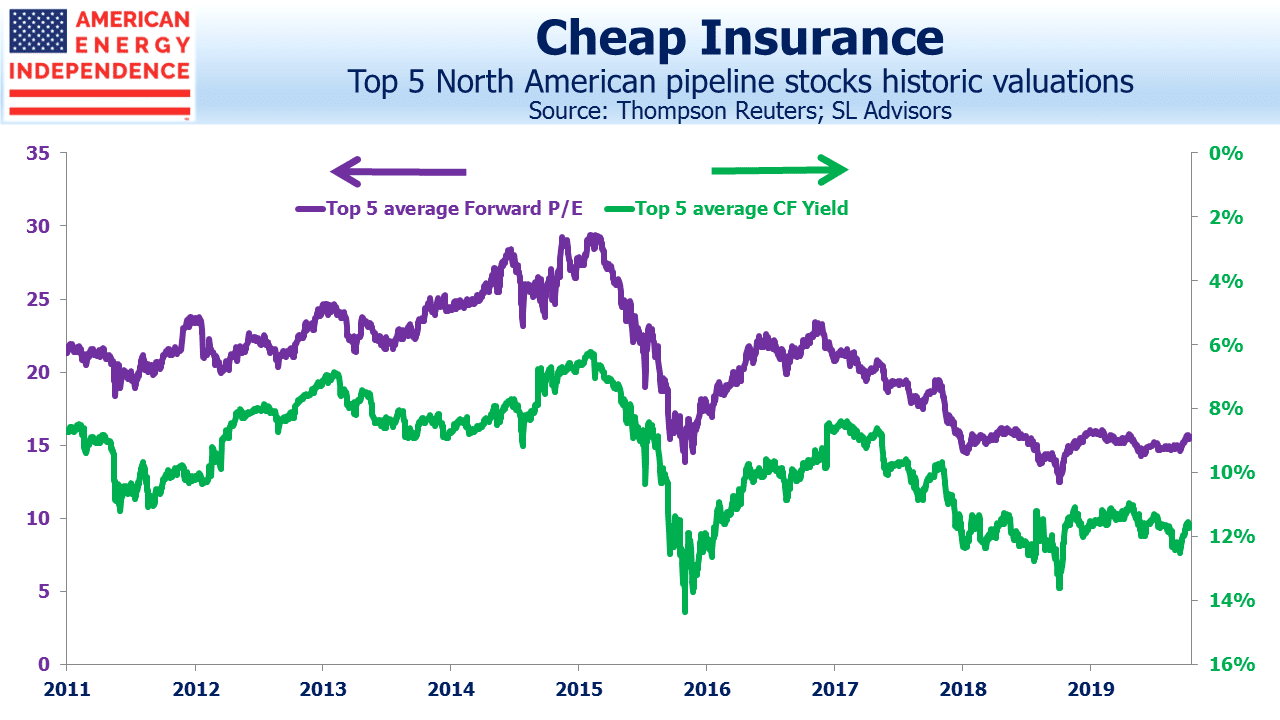

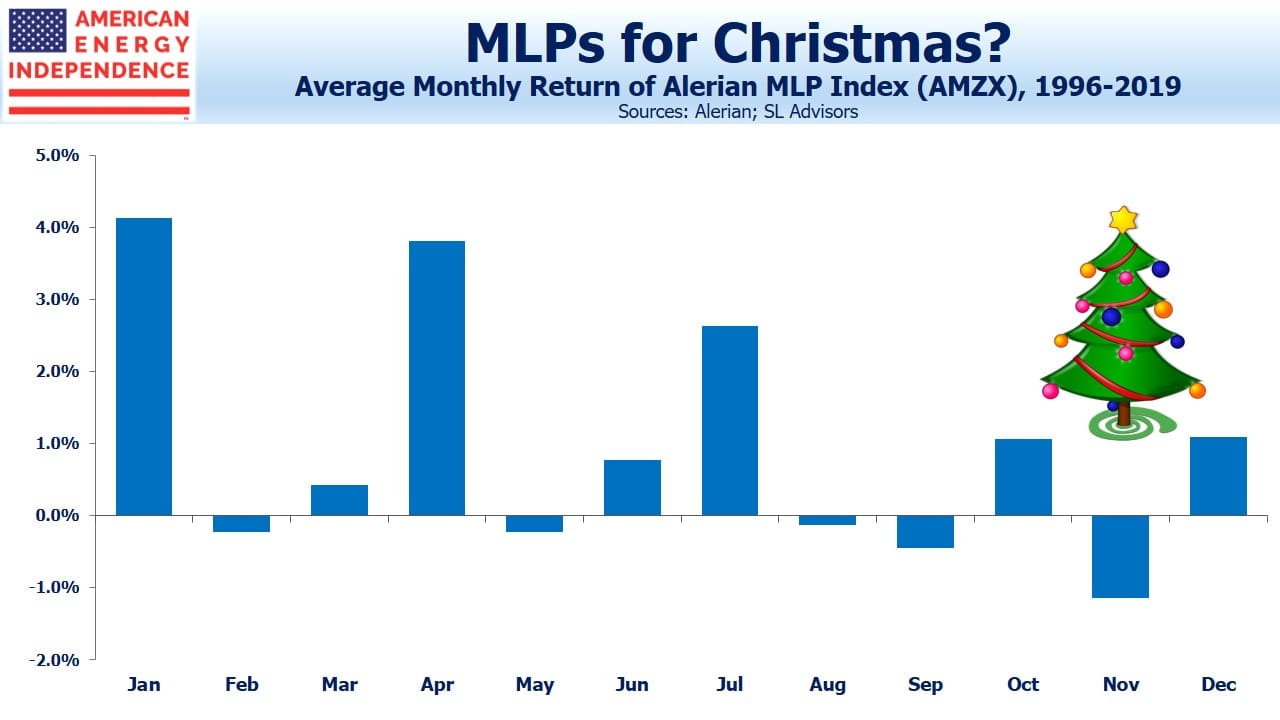

The sector is cheap enough that an investor can awaiting a re-pricing catalyst, which could be conflict in the Middle East or simply the market’s ultimate recognition of improving fundamentals.

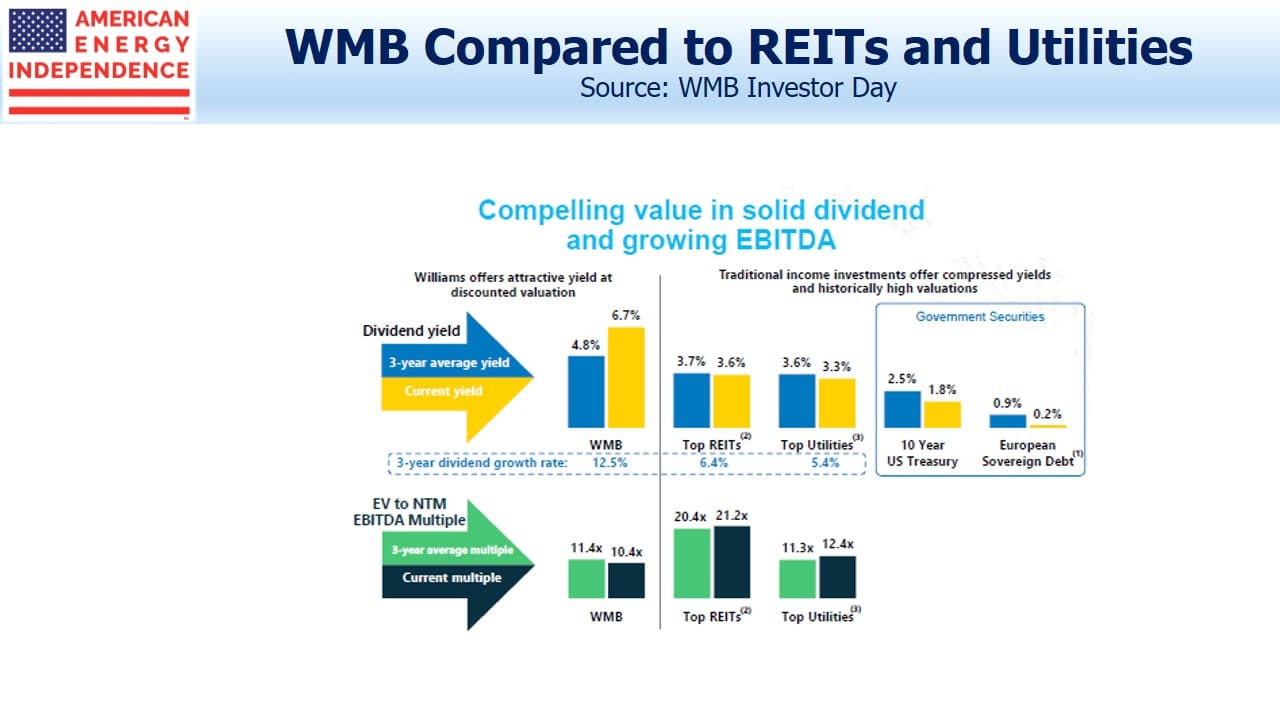

Although S&P500 valuations are historically high, at over 18X 2020 earnings, the five biggest North American midstream infrastructure names trade at almost a 20% discount. All five of these companies are in the American Energy Independence Index.

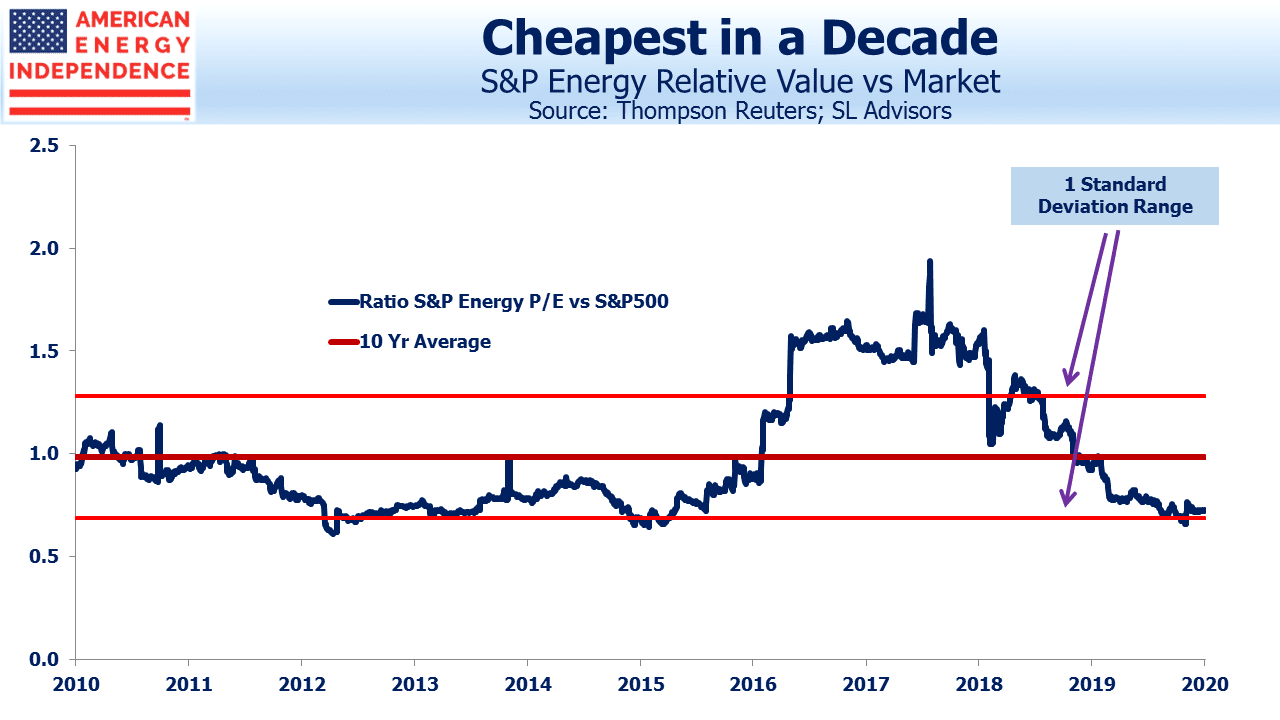

S&P Energy, having sunk to 4% of the S&P500, is at close to its cheapest relative multiple in a decade.

There’s no need to correctly forecast disruptive geopolitical events or react quickly to them. Pipeline stocks are cheap enough to provide holders with multiple potential ways to make money.

We are invested in all the names listed above.