Criticizing MLPs Helps Them

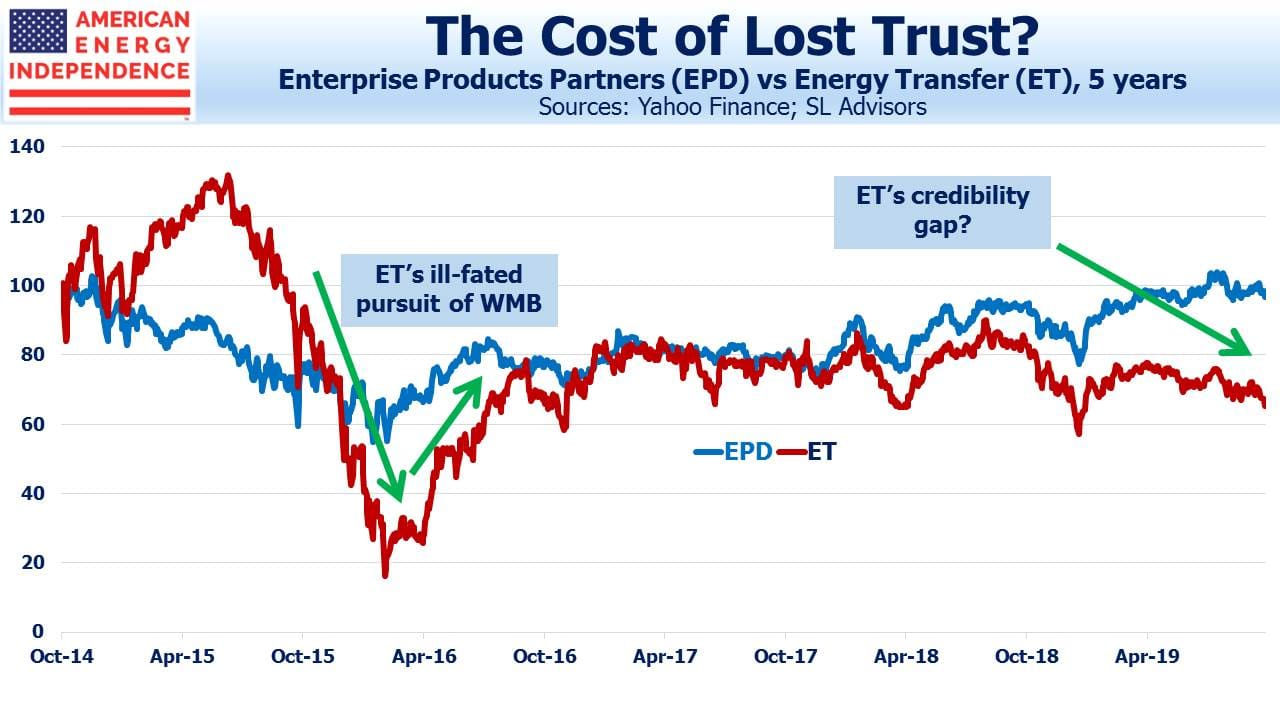

Wednesday’s blog, Energy Transfer’s Weak Governance Costs Them drew a record number of pageviews within a few hours of being posted. It’s not just because Energy Transfer (ET) is a large, widely held MLP. Much of the writing in the sector is from cheerleaders who don’t criticize the companies they follow, because it’ll hurt their business model. Commentary is largely anodyne, and useless. Running an investment firm that doesn’t have a complex web of relationships with its portfolio companies provides a wonderfully liberating writing environment.

Sometimes readers ask why we own a stock if we’ve just been critical of its management. It’s possible to find a stock attractively cheap, and yet lament prior actions of its executives. That’s often why it’s cheap. ET is a well-run company. CEO Kelcy Warren has assembled a team that knows how to execute. If investors trusted him more, the stock would be higher. It’s worth pointing out.

Pageviews on our blog reveal that investors find criticism far more helpful than sycophantic platitudes. For those who desire an irreverent spin on the energy sector delivered with rapier-like wit, follow @Mrs_Skilling, an anonymous and astute energy insider who will simultaneously educate and amuse you. Often, posts are laugh out loud funny.

In case it gets lost in the cut and thrust of calling out bad management behavior, U.S. midstream energy infrastructure is a compelling investment opportunity. The Shale Revolution is almost entirely an American success story (see Why the Shale Revolution Could Only Happen in America). The technology behind fracking was developed in America because new business formation, access to capital and constant striving for success are more present here than anywhere. Add to those advantages an already substantial energy sector with thousands of skilled workers supported by extensive infrastructure.

Privately-owned mineral rights are an additional unique feature that allows landowners to negotiate with energy companies to extract what lies beneath on mutually beneficial terms. Mineral rights belong to the government all over the world, including in the UK, whose legal system is the basis for much of ours.

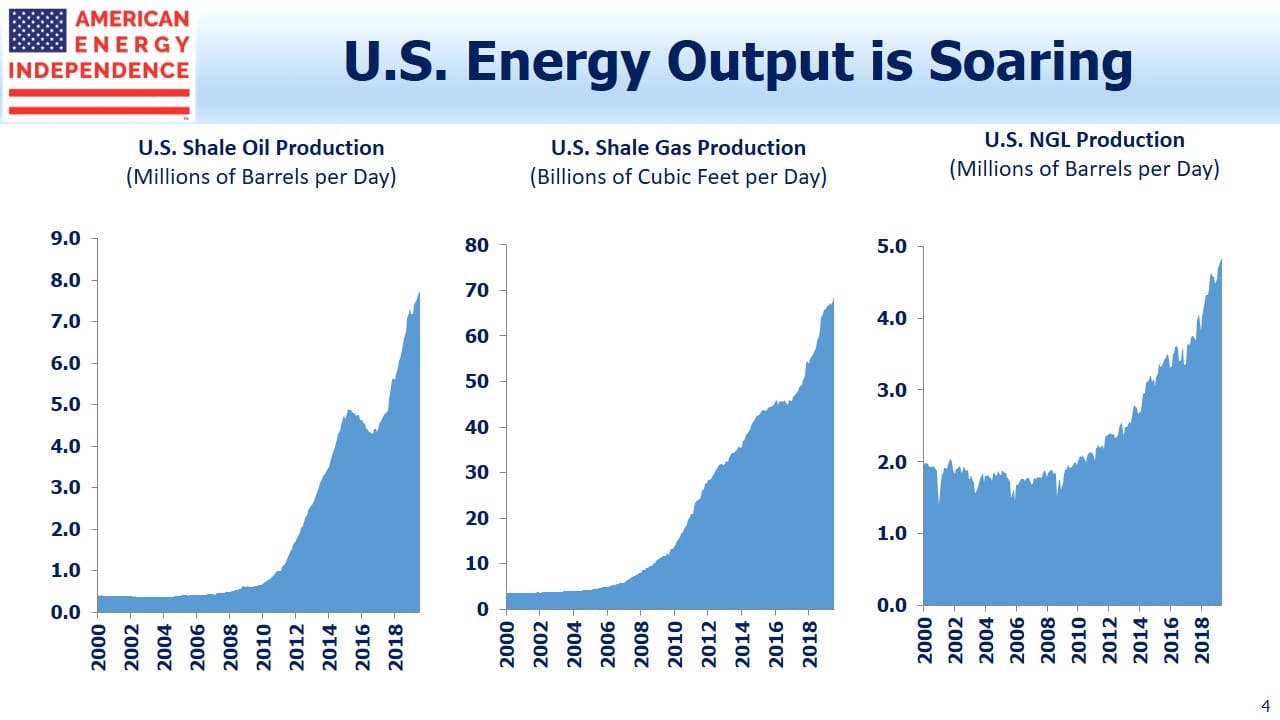

The result has been an American energy renaissance that has released new supplies of oil and gas, and made the U.S. the world’s biggest producer. Ten years ago few thought such an outcome possible.

Moreover, shale production is short cycle (see Shale Cycles Faster, Boosting Returns). Because the deployment of capital is more synchronized with production than conventional projects (think years and $BNs spent before production emerges as the traditional model), it’s less risky. Capital is recycled more rapidly, allowing production to be more responsive to price changes.

This is why it’s attracting the world’s biggest oil and gas companies. Exxon Mobil (XOM) is the most active driller in the Permian basin in Texas, where it is targeting one million barrels per day (MMB/D) of output in five years. Chevron (CVX) is close behind, with a 0.9 MMB/D goal.

Warren Buffett famously quipped that, had he been at Kitty Hawk in 1903 he could have shot down the Wright Brothers’ plane, thereby saving future airline investors from losing $BNs over the following decades. History is full of great ideas that didn’t immediately profit their inventors, often because too much capital followed the opportunity.

U.S. shale production of oil, gas and natural gas liquids will find a level at which returns on invested capital are adequate. It may already be there. It’s not always clear whose investment in upstream production will be most profitable. In the Barnett Shale, where the shale boom began, production peaked in late 2011 and only a handful of rigs remain active today.

Output will ultimately calibrate to a sustainable level of capital investment. Countless companies have provided proof of concept, although investment returns have been frustratingly disappointing. The growing presence of XOM and CVX is substantial confirmation that this is a permanent piece of the world’s energy markets.

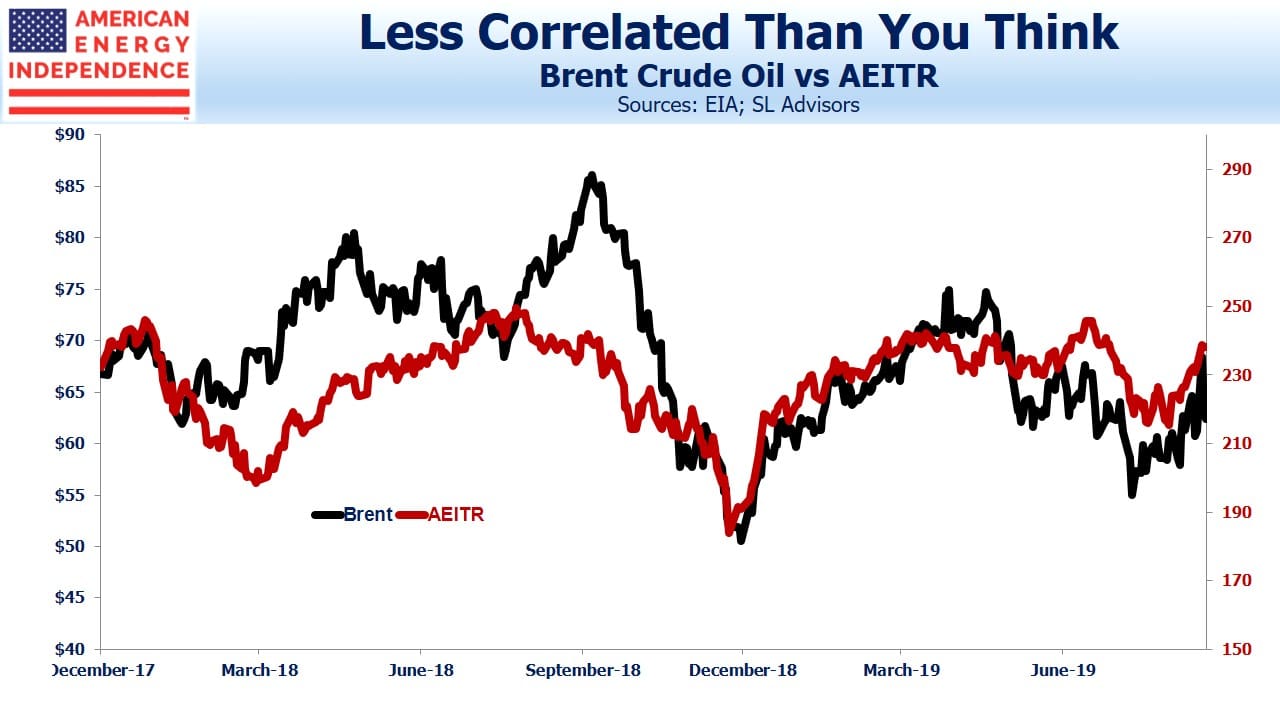

Shale production has performed far better than investments in it. Midstream infrastructure, the pipelines, storage assets and processing facilities that sit between the wellhead and the customer, remains out of favor despite record volumes. This is also largely an issue of capital allocation, with the original income-seeking investors understandably alienated as the sector cut distributions to pay for new growth projects (see It’s the Distributions, Stupid!). But capex is falling, finally setting the stage for a surge in free cash flow (see The Coming Pipeline Cash Gusher).

Criticism of individual companies is intended to draw attention to ways they could improve their behavior, lifting stock prices to the benefit of all investors. The Shale Revolution remains a huge success story for production, highlighting much that is great about America. The companies that own these critical pipelines linking producers to consumers will continue to benefit from these growing volumes. Those who focus on valuations rather than past performance are likely to realize commensurate returns in the midstream.

We are invested in ET