Private Equity, Private Valuations

Last week Cowen held a two day energy conference. Presenting companies included upstream and service providers, so although there were no midstream energy infrastructure companies present it provided useful background for current operating conditions.

Baker Hughes (BKR) is one of three large diversified services companies supporting the sector, along with Schlumberger and Halliburton. BKR CFO Brian Worrell provided an upbeat outlook following their recent spinout from GE. They cleverly describe themselves as a “fullstream” company (i.e., covering upstream to downstream). Listening to Worrell, it’d be hard to remember how negative investor sentiment is within energy. Consensus estimates for BKR’s 2019-21 EBITDA growth rate are 15%.

Worrell provided some interesting background on a partnership they have with AI firm C3. Predictive Asset Maintenance, one of their offerings, analyzes operating data from customer equipment to anticipate breakdowns, allowing repairs to be done pre-emptively. BKR is C3’s exclusive partner in the energy sector. They have 200 customers.

Another interesting theme was the influence of Private Equity (PE) investors. Independence Contract Drilling (ICD) is a micro-cap drilling company clearly wrestling with the downturn in shale-related rig demand. One participant asked if they’d considered a sale or merger. President and CEO Anthony Gallegos noted a recent negotiation with a competing privately owned firm which foundered when the PE backer insisted their drilling rigs were worth $18MM each while ICD’s stock price placed an implicit value of only $6MM for its similar equipment.

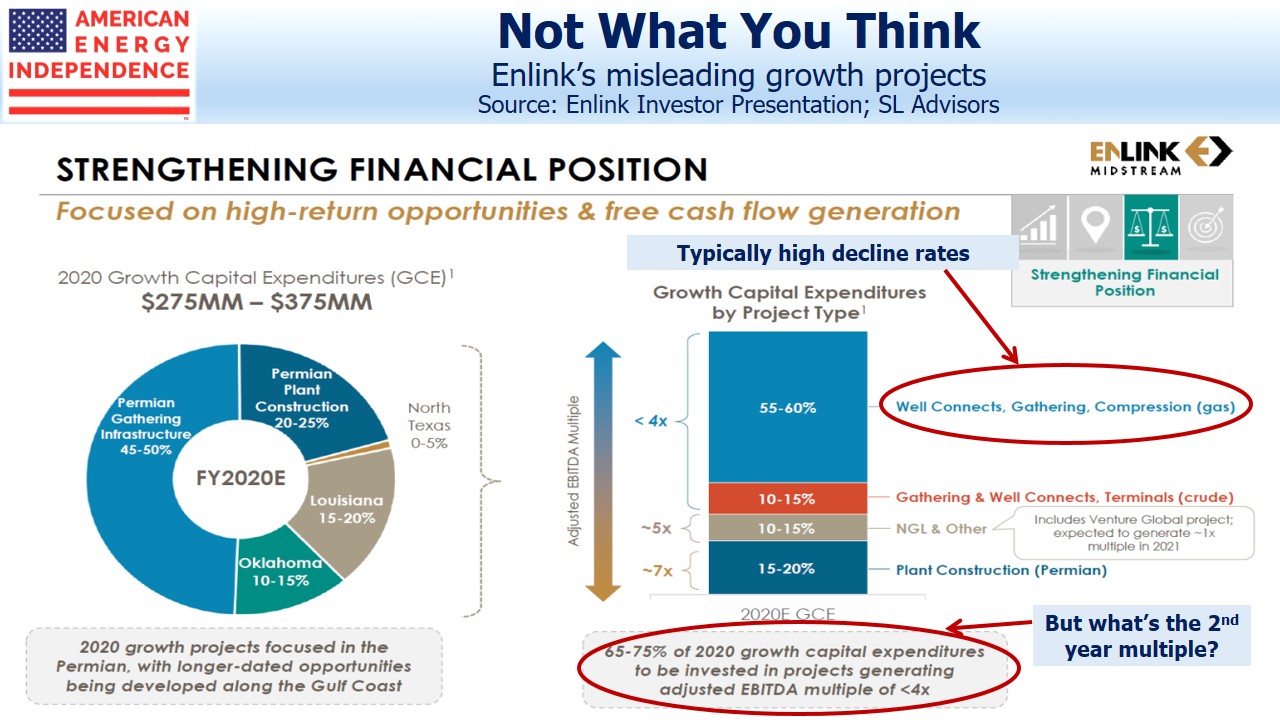

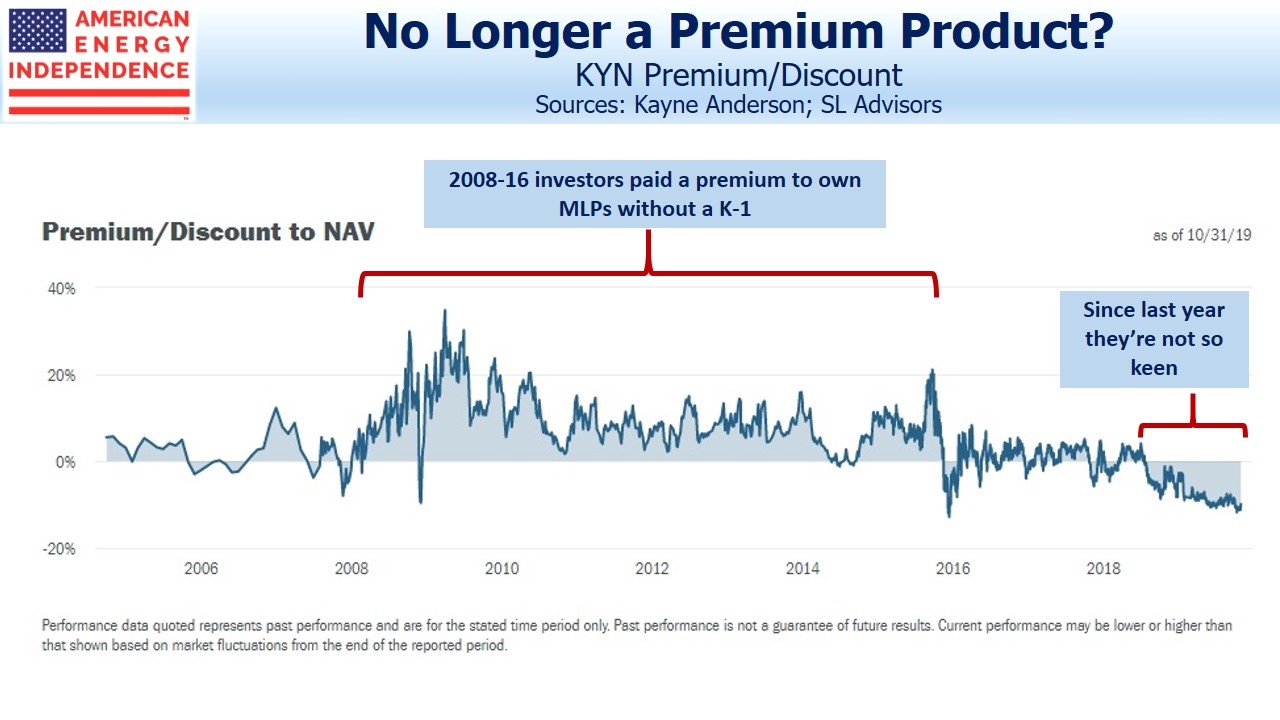

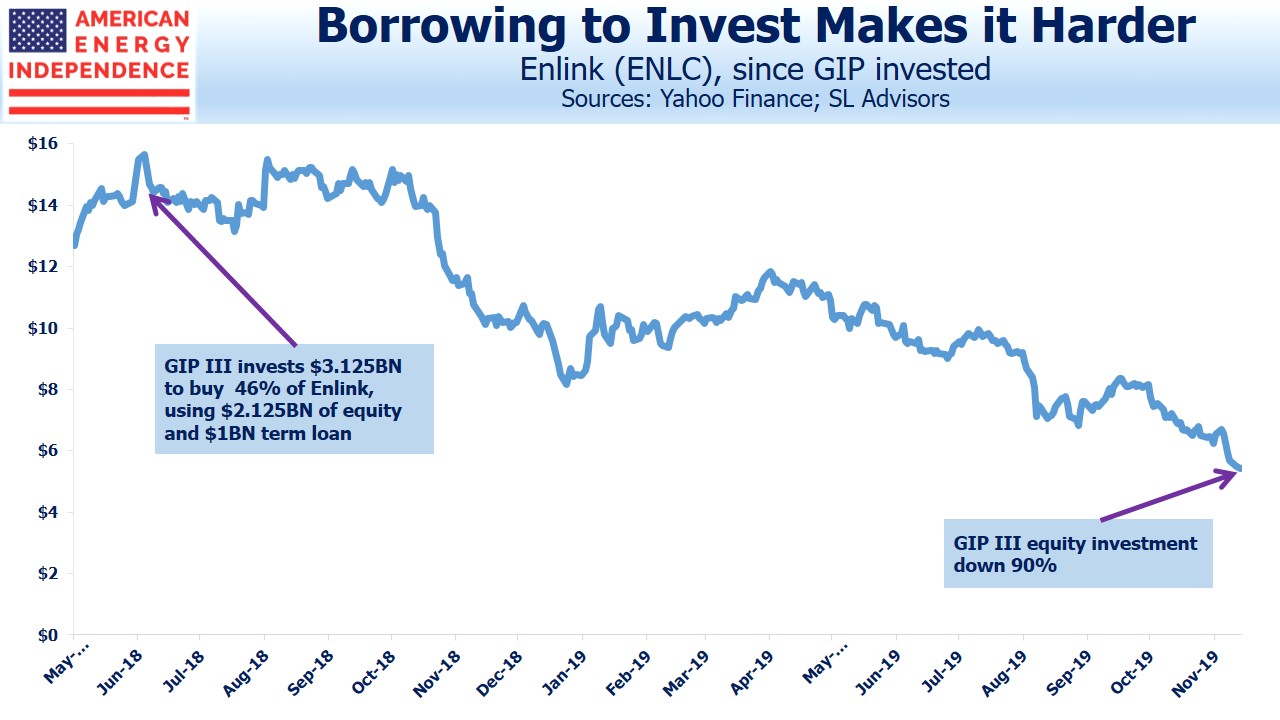

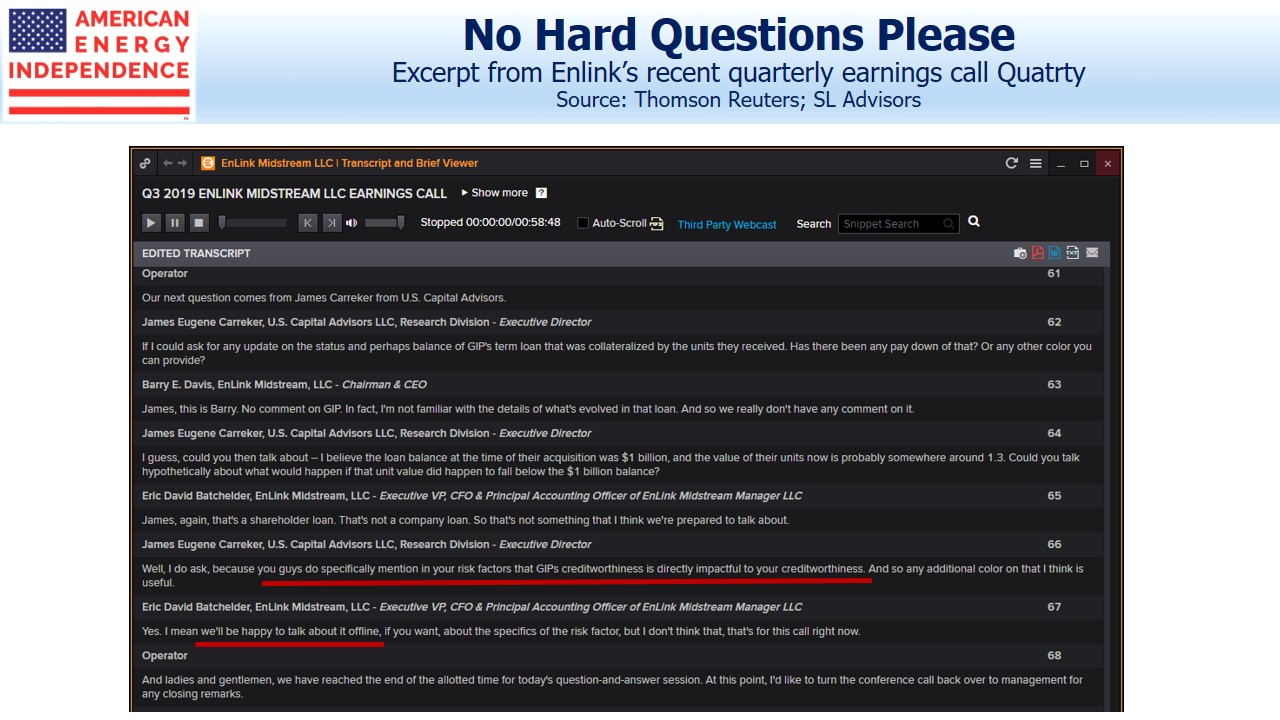

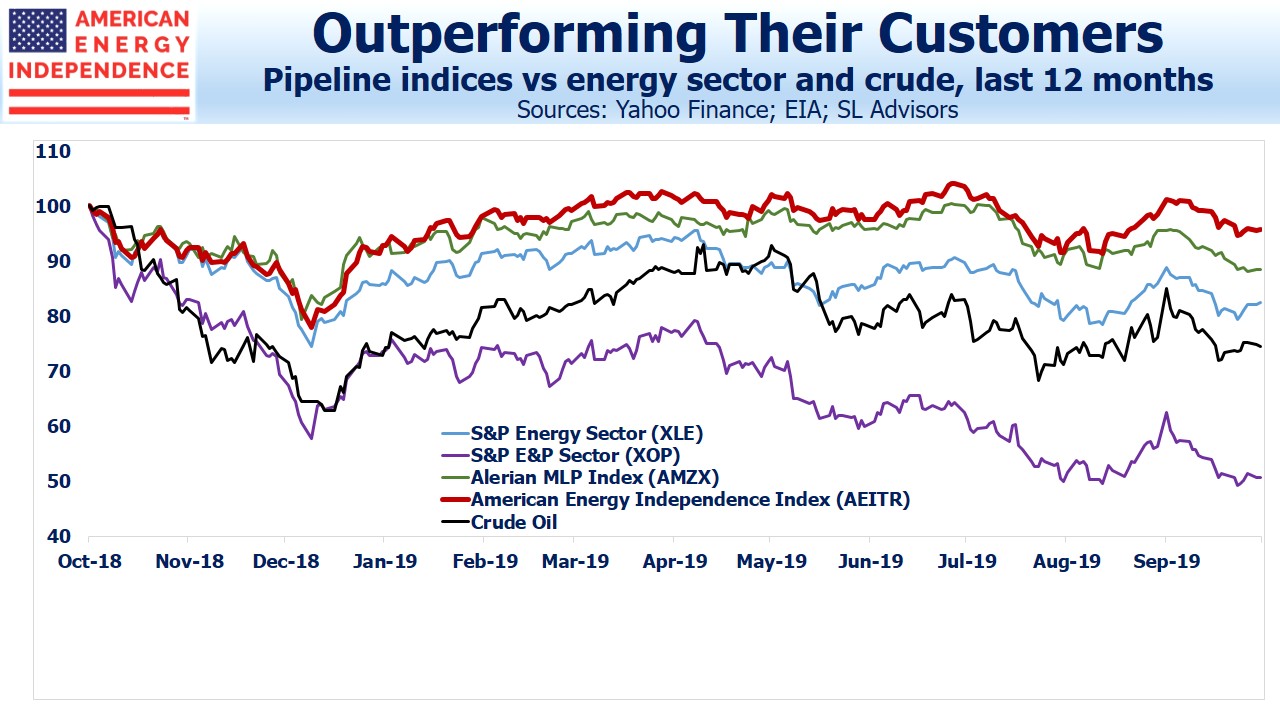

There’s plenty of evidence that PE firms assess more value in publicly traded energy sector equities than the public markets themselves. PE investments in midstream energy infrastructure have slowed down in recent months, although it’s still been an active year. But there are questions about valuation.

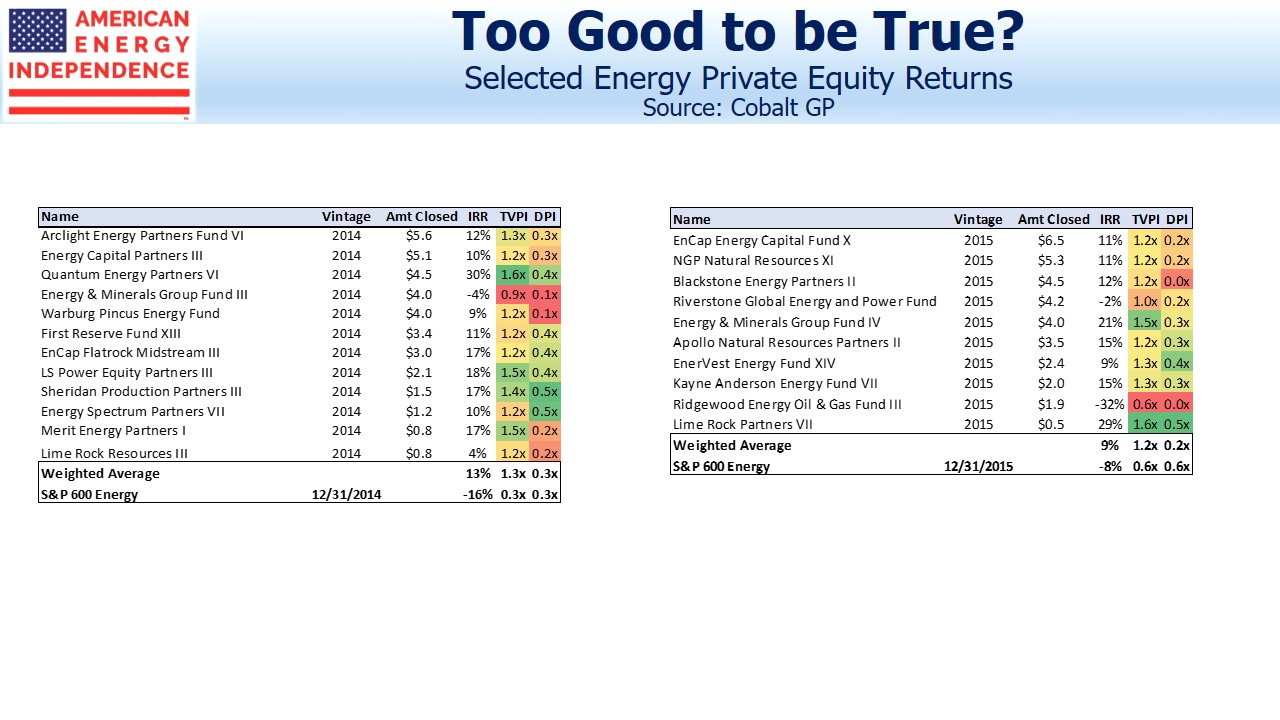

Energy-focused PE funds saw their highest inflows in 2014, when the sector peaked. This isn’t surprising, since fund flows invariably follow performance. But what’s odd is that fund returns since then are well ahead of the S&P600 Energy Index.

Although PE funds deploy capital over several years and likely made investments through the 2016 low, the recovery since then has been modest. It suggests that valuations are not rigorous – PE firms have a great deal of latitude in making estimates. Fees and the ability to raise subsequent funds both benefit from higher valuations.

PE energy funds continue to raise capital, supported in part by the returns they show on prior funds. The illiquidity of private investments is supposed to generate a modest return premium, but research from Cobalt GP reveals that so far these funds are claiming to beat public markets by 15-30%. Total Value to Paid In (TVPI) suggests these fund managers have chosen well, and is the basis for their IRRs. But Distributions to Paid In (DPI) are well under 1.0X even for funds that are five years old, showing that the IRRs rely heavily on the valuations of current holdings. As cash distributions increase, the time of reckoning will arrive when investors will learn how accurate these interim IRRs have been.

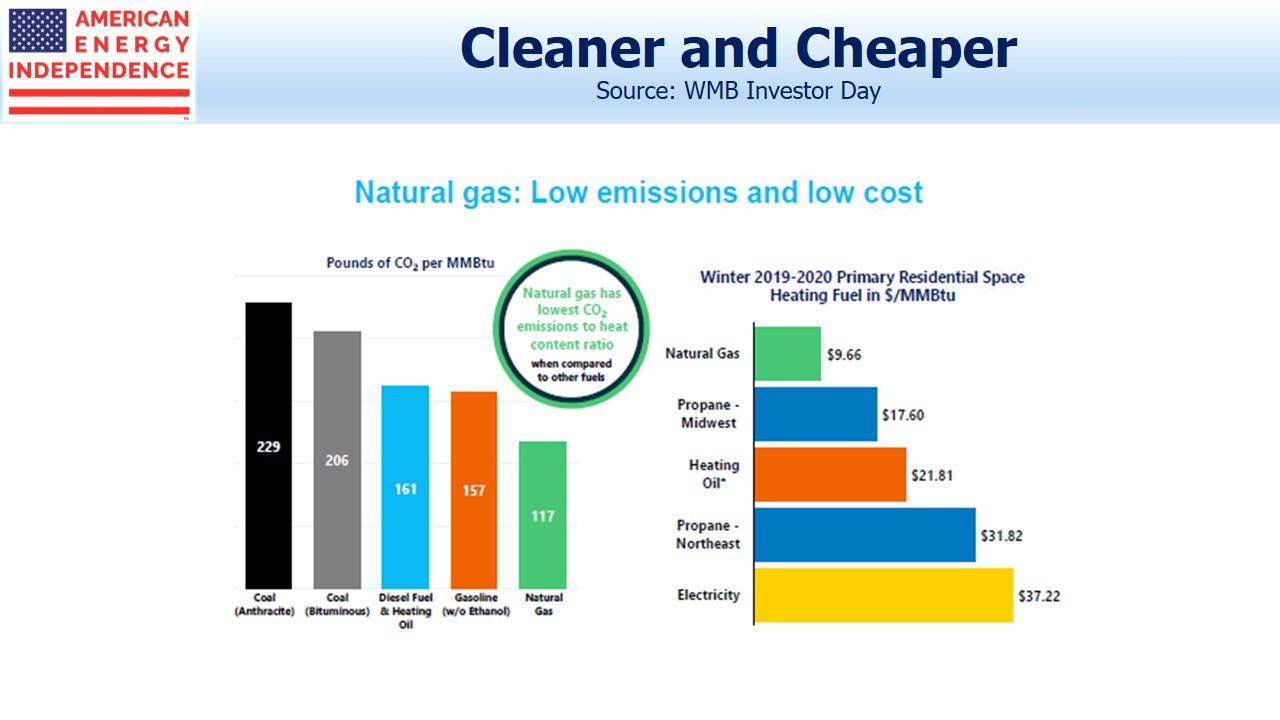

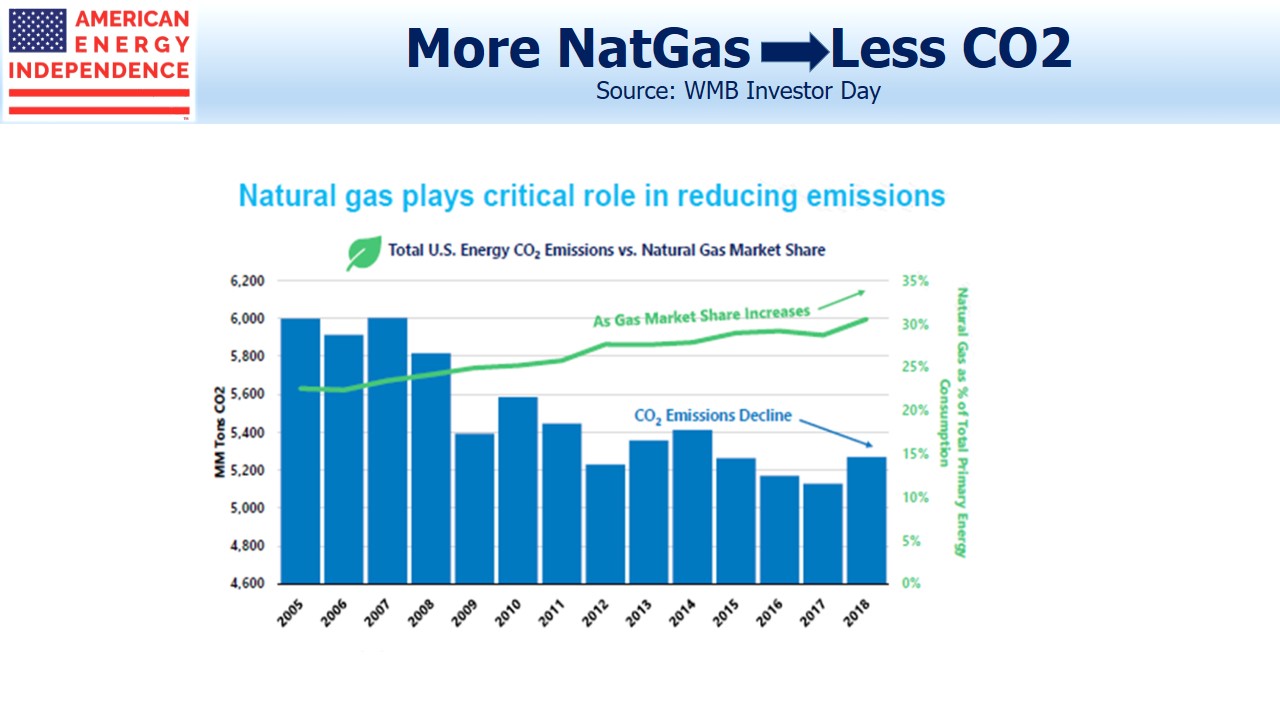

On a different topic, the magazine cover contrary indicator theory posits that when a topic or person becomes mainstream, interest soon peaks. Credit friend Barry Knapp, CEO and founder of Ironsides Macroeconomics, for being first to predict that high school dropout Greta Thunberg’s selection as Time’s Person of the Year likely marks a peak in interest in climate change.