Updating the Coming Pipeline Cash Gusher

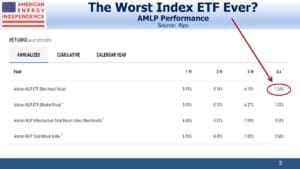

Almost a year ago, we published The Coming Pipeline Cash Gusher. Midstream energy infrastructure companies, especially MLPs, have long relied on Distributable Cash Flow (DCF) as a measure of profits available for distributions. As the funding needs of growth projects increased, the difference between DCF and Free Cash Flow (FCF) became stark. FCF is a GAAP term and more widely recognized by the broad investment community. MLPs have destroyed the trust of their original investors, because the gulf between DCF and FCF led to distribution cuts. Drawing a new set of investors requires describing results in a recognizable form, and FCF is part of that effort.

Last April, we showed that the need for growth capex had peaked, and that existing assets were generating increasing amounts of cash. Both of these developments are positive for FCF. In combination, they produced a startling trajectory. We calculated that over 2018-21, FCF would leap from $1BN to $45BN – very meaningful for a sector with a market cap of around $450BN.

We did this analysis on the American Energy Independence Index (AEITR), because it’s the broadest representation of North American midstream energy infrastructure companies. It’s the only index that omits companies that pay Incentive Distribution Rights (IDRs) to a controlling general partner. Paying IDRs increases a company’s cost of capital and is the most visible evidence of a misalignment of interests between management and investors. We never invest in a company that pays IDRs, and where available we hold companies that receive IDRs from someone else.

Now that 2019 earnings have been reported, capex guidance for 2020 is available and we’ve updated our forecast. FCF is still set to soar – albeit not quite as fast by 2021 as we found a year ago. But a closer look at the figures reveals a story just as positive. Growing FCF remains the most compelling bull case for this sector.

We should note that the forward guidance that we’ve used was all provided by companies before the market’s sudden drop in response to Covid-19. There’s a strong case to expect domestic pipelines to fare better than most businesses in an economic slowdown, but we’ll explore that topic in more detail in another blog post.

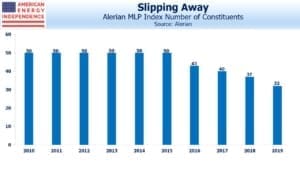

We now forecast 2021 FCF to be around $41BN, $4BN less than we thought last year. $0.5 of this is because of changes to index membership. Some names have joined the index – either because they dropped IDRs which had previously disqualified them, or because they’re a recent IPO. Others left the index because they were acquired, either by another public company or by a private equity buyer. For today’s index members who were in a year ago, our 2021 FCF forecast has come down by $3.5BN.

For the 28 members of the AEITR who remained in the index since last year, 2019 FCF came in $4.5BN ahead of our April 2019 forecast. TC Energy (TRP) was the biggest surprise here, with $1.1BN of FCF versus our prior forecast of $0.1BN. As we’ve noted before, along with Enbridge (ENB), which also came in $0.6BN ahead of our expectation, the two big Canadian firms generated $4.9BN of the $9.2BN in AEITR 2019 FCF. As more American companies emulate the financial discipline of our neighbors up north, FCF will grow.

Other positive surprises came from Energy Transfer (ET) at $2.1BN versus $0.9BN, Cheniere Energy (LNG) at $1.0BN vs $0 and MLPX at $1.3BN vs $0.5BN. The biggest miss came from Enterprise Products Partners (EPD). Over the 2019-21 period, we estimate their FCF will now be $3.6BN less than we thought a year ago. Their growth capex guidance is now $1BN per annum more than it was previously. Following their 3Q19 earnings report, EPD added $3.6BN to their backlog. The bulk of this spending is going towards expanding the Midland to Echo crude oil pipeline system. They’re also investing $1.5BN in a second propane dehydrogenation facility, which will convert propane into propylene for later use in combustion and plastics. The Shale Revolution isn’t just about oil and natural gas – natural gas liquids, such as propane, have also created new business opportunities. EPD’s history of capital discipline and reliable distributions gives them more latitude than many to pursue growth projects.

EPD stands out in significantly increasing their growth capex – most companies have made only modest changes, although ET raised their capex guidance too, partly because of their acquisition of Semgroup.

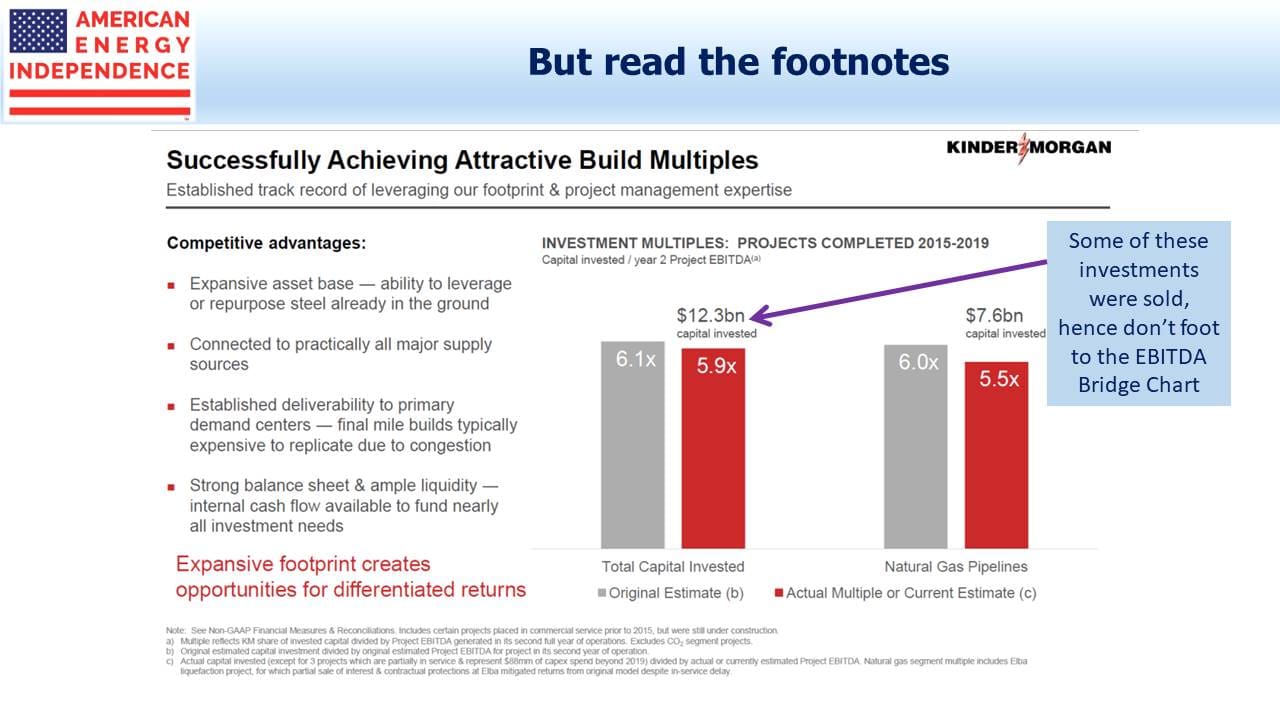

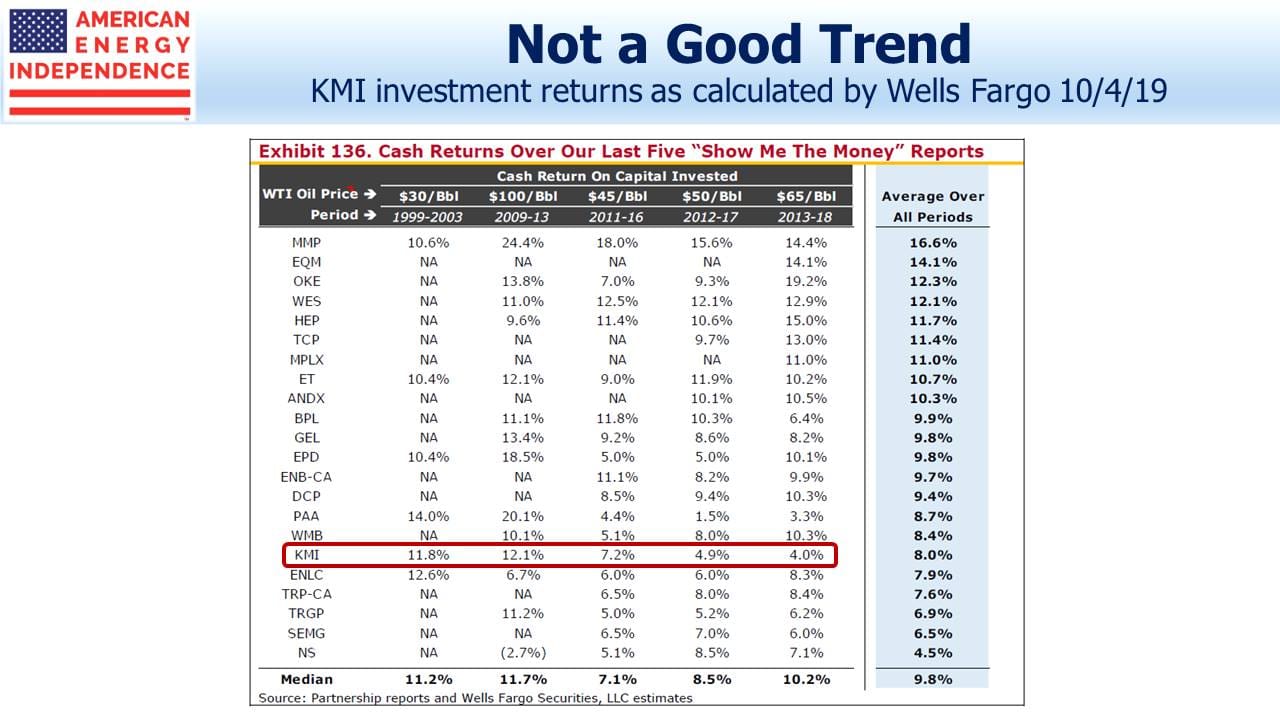

For 2021, Kinder Morgan (KMI) and ENB each raised growth capex by $1BN. So the $4BN drop in 2021 forecast FCF for the sector is largely because these two companies, along with EPD, have raised their spending plans.

Nonetheless, some of the increases in FCF 2019-21 are big. Ten names will collectively increase FCF by $12BN over this period. ENB and KMI could both add almost $3BN apiece 2020-21.

Energy remains out of favor, with pundits like Jim Cramer dubbing it the “new tobacco” and some calling it “uninvestable”. Climate extremists direct their anger at 80% of the world’s energy supply with no practical solutions. Although it may sound as if investors are shunning stocks because of fear that public policy will harm their prospects, TRP and ENB both outperformed the S&P500 last year. That these two were most of the sector’s FCF suggests that explanations for poor stock performance are more driven by capital allocation. As FCF growth becomes more widespread, investors will find more to like.