Crude Catches a Virus

We’re in one of those times when everything is a macro call. Stocks and sectors are, for now, more highly correlated, since Coronavirus developments are dominant. Click here for some cool graphics illustrating its spread. The recent recovery in stocks echoes the information on the link.

We won’t attempt to offer any insight on the virus, but have some observations on energy markets.

Recent reports suggest that China’s crude demand is down by around 20%, or 3 million barrels per day (MMB/D). OPEC is apparently considering temporary cuts of 0.5 MMB/D and could perhaps reduce by 1 MMB/D. That still leaves the market over-supplied by 2.0-2.5 MMB/D, although China’s imports should hold up relatively better as it builds strategic reserves.

Libya’s production has fallen by around 1 MMB/D, from 1.2MMB/D to just 0.2 MMB/D recently, because of the ongoing civil war there. However, they are holding peace talks and a cease-fire agreement may be reached soon.

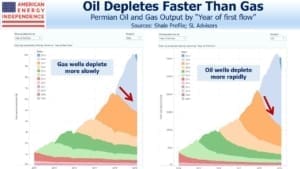

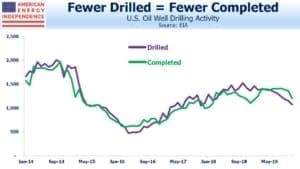

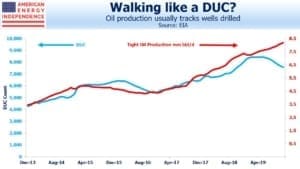

Before the Coronavirus hurt demand, we had thought U.S. shale output was likely to come in below expectations (see Why Oil Production May Disappoint). Oil wells experience faster depletion than natural gas, which means that as shale production grows an ever increasing number of new wells is needed to compensate for the production drop-off experienced by older wells. We also noted the sharp drop in “DUCs” (Drilled but not yet Completed), which become the source of future production when they’re completed.

Schlumberger, the world’s largest oil field services company, recently announced plans to pull back from shale oil because they see so many E&P companies struggling to be profitable. In announcing results last month, CEO Olivier Le Peuch said, “North America revenue of $2.5 billion…dropped 14% sequentially due to customer budget exhaustion and cash flow constraints.”

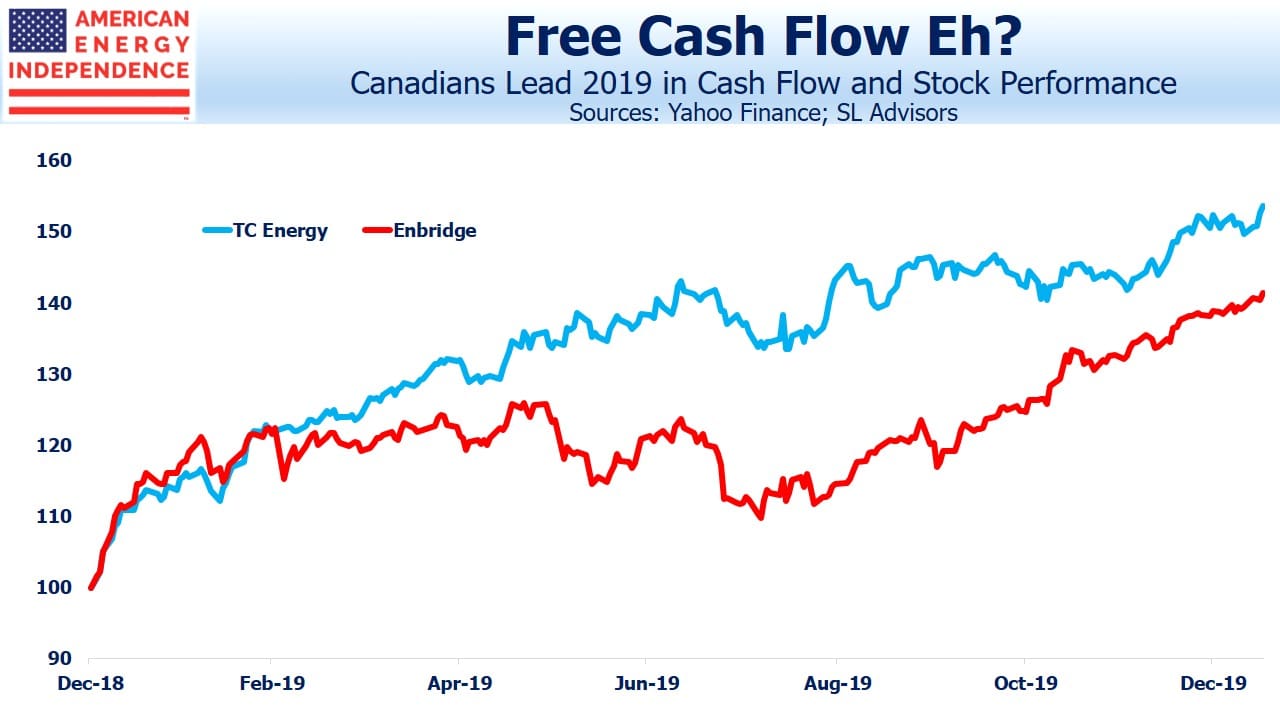

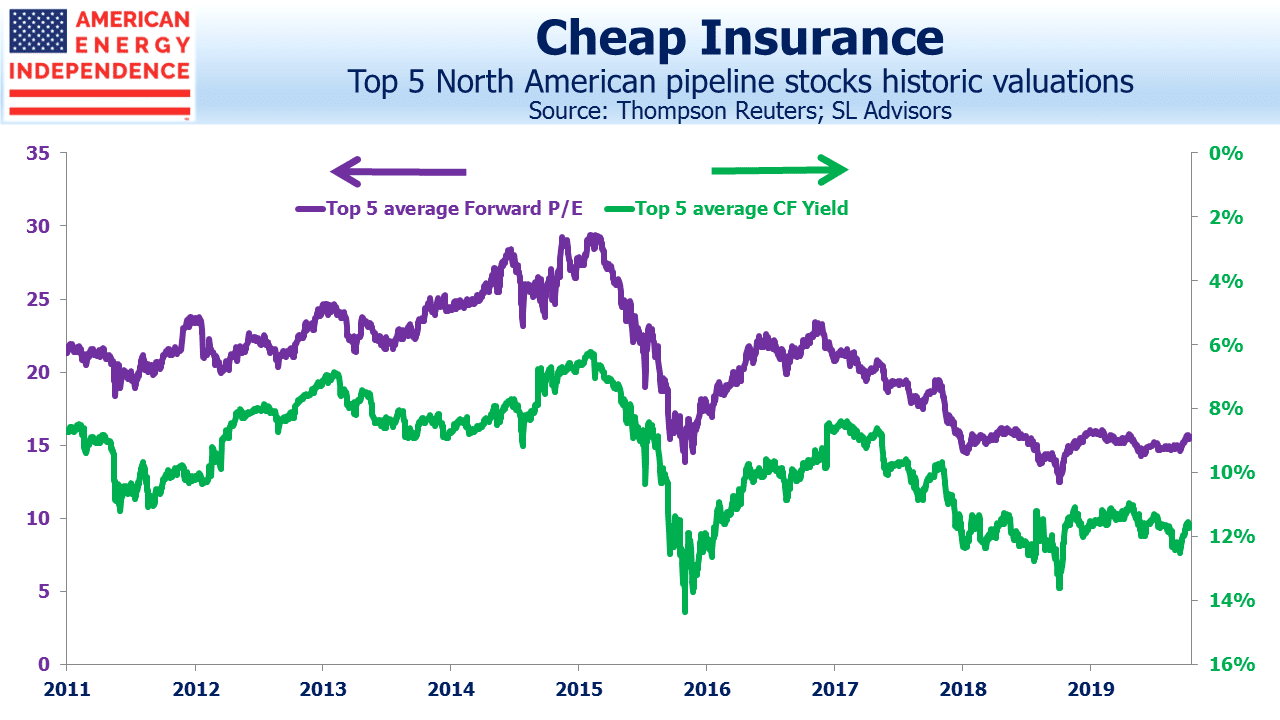

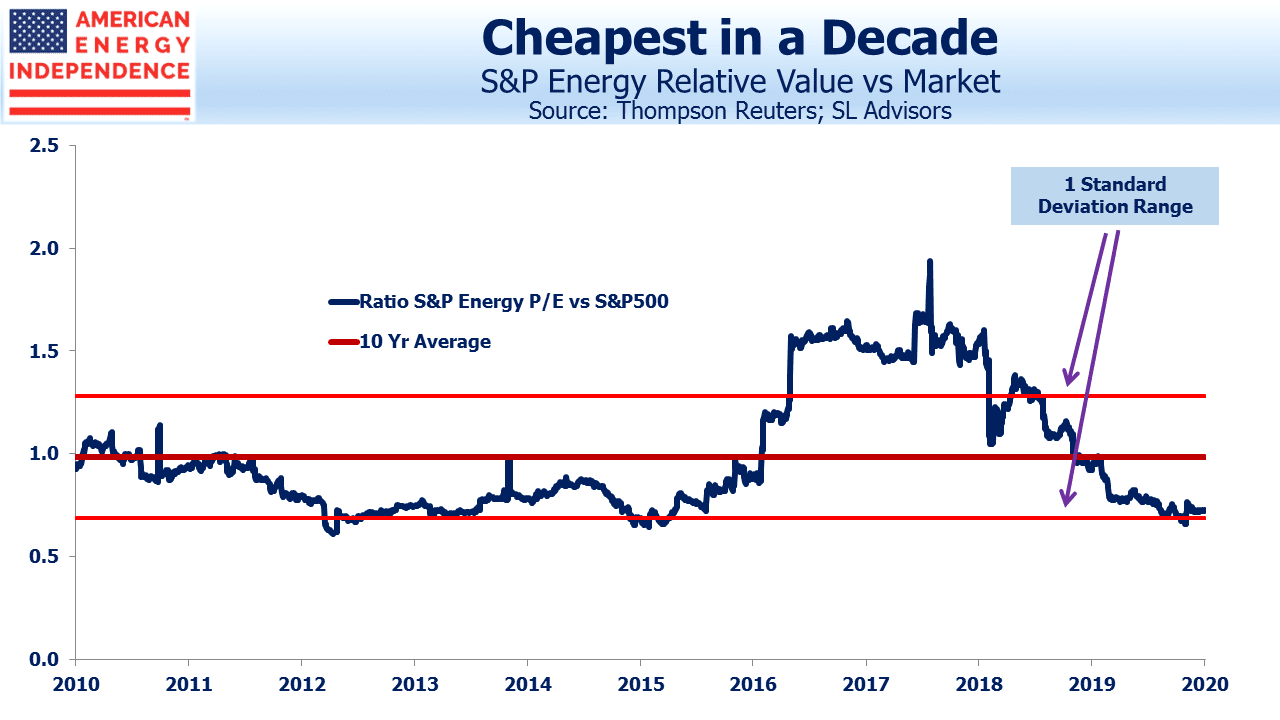

Capital is clearly becoming constrained. Natural gas-dedicated E&P names such as Chesapeake and Range Resources have seen their stock fall 95% or more from peak levels more than five years ago. Even the biggest companies such as Exxon Mobil trade at historically low valuations.

The rig count has been sliding for some time amid weak crude oil prices and steadily sinking natural gas. The Coronavirus-driven sudden drop in crude prices is likely to cause a further pullback in the rig count drilling for shale oil, restraining production growth.

The caveat is increasing efficiency of production. The U.S. Energy Information Administration recently noted that oil and gas production grew in 2018 even while the number of wells in operation fell 10%. Doing more with less has been a hallmark of the Shale Revolution since its infancy. However, this reaches a limit as the least efficient rigs drilling the highest cost acreage are the first to be laid down, leaving the high-tech rigs in the sweet spots.

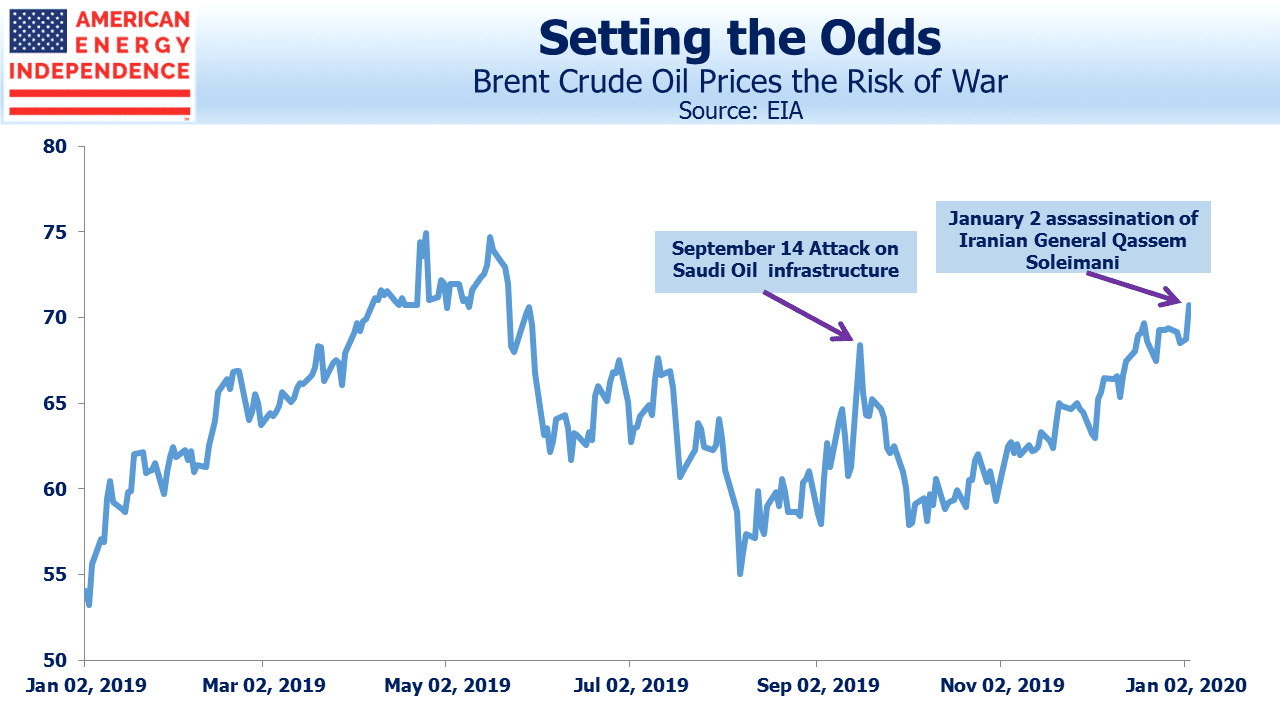

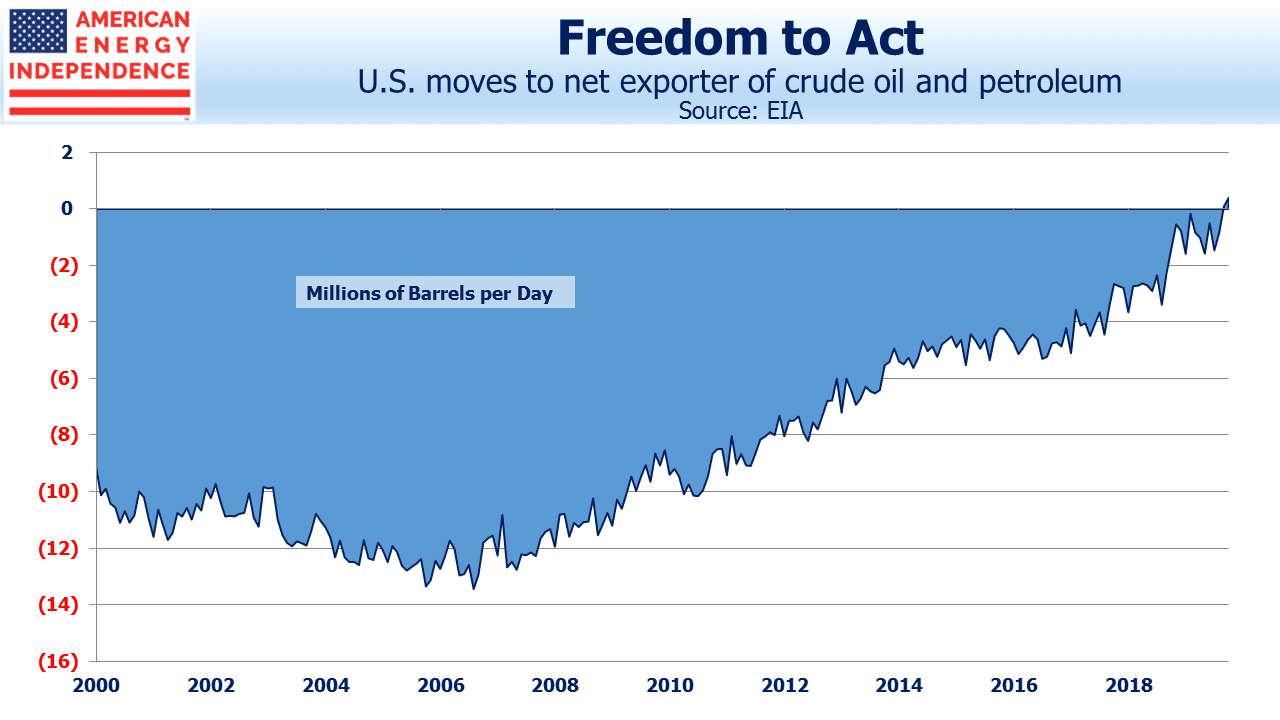

Depending on the length of economic disruption caused by the Coronavirus, supply may need to adjust. Low prices are the best cure for oversupply. Saudi Arabia has signaled they’re willing to cut production with OPEC to get the price of oil higher, and can maintain its lower production quotas after demand has recovered. U.S. activity demonstrates that shale oil growth was already moderating before recent developments. Meanwhile, many forecasts see the physical oil markets shifting to a multi-year deficit in the back half of 2020 and tension in the middle east remains elevated as the US continues its maximum pressure policy of sanctions on Iran. With the many cross-currents, energy investors remain on the edge of their seats.