More Solid Pipeline Results

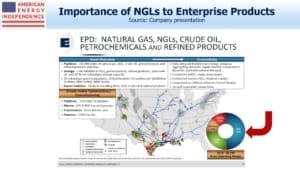

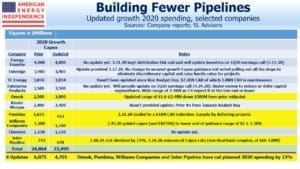

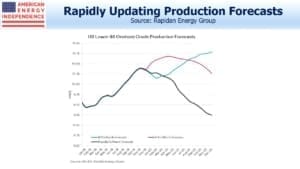

Earnings season for big pipeline companies has continued to be encouraging. Enterprise Products (EPD) reported results largely as expected and lowered 2020 growth spending by $1BN. The reductions in capex have been welcomed by investors who have long complained about the level of reinvestment by energy companies. Any reductions in EBITDA have been matched by lower outlays on new projects, which supports free cash flow.

Jim Teague, EPD’s CEO, opened the call by remembering an outbreak of polio as a young boy, “It was a highly contagious virus. It struck without warning…my mom contracted polio…we practiced our own kind of social distancing. What I don’t remember is shutting down the entire economy and 30 million people losing their jobs in one month.”

Teague offered another personal perspective, ”As a young naval officer in an attack helicopter squadron in the Mekong Delta, Vietnam, I took a great deal of pride that I was part of a special fraternity. I have that same kind of pride today.” The wartime analogy strikes a chord with many.

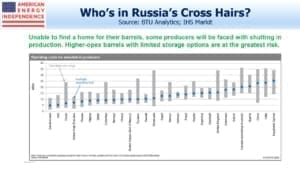

EPD maintained its distribution. When asked about customers claiming force majeure to get out of take-or-pay pipeline contracts, Teague responded, “We’ve looked at all our contracts, and we feel pretty comfortable that we’re not going to have any issue with force majeure as it relates to price.”

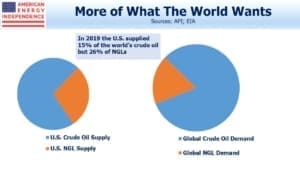

Cheniere Energy handily beat expectations with their 1Q20 results. Of more concern to investors is the outlook for Liquified Natural Gas (LNG) shipments, with reports of as many as 20 being delated or cancelled. CEO Jack Fusco addressed this in his opening remarks,”…our long term contracts do not include provisions for renegotiations.” He added, “In instances where that (cancelation) occurs, the fixed liquefaction fee is still paid to us and our marketing affiliate has the option to market the volume into the global marketplace.”

Cheniere continues to expand their export facilities, both at Sabine Pass, LA where they’re adding a sixth train and also at Corpus Christie, TX. They don’t expect coronavirus to harm either the cost or completion schedule of these projects. They reaffirmed previous full year guidance on distributable cash flow and EBITDA.

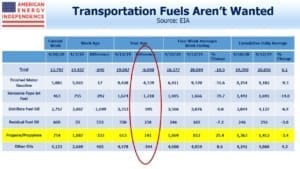

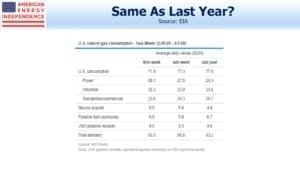

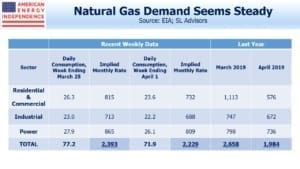

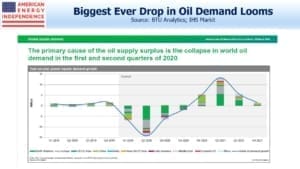

Magellan Midstream provided some interesting recent volume statistics, in that refined product demand was down 24% in April but “only” 20% in the last week of April. CEO Mike Mears thinks that this category could return to last year’s levels by 3Q20, which most would agree is more positive than consensus.

One analyst asked about interest from private equity firms in acquiring publicly traded MLPs. Mears responded, “We haven’t spent a lot of time talking to private equity firms about acquiring Magellan. That wouldn’t be at the top of our list.”

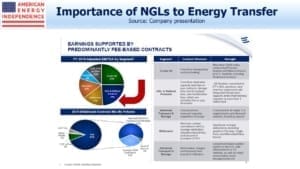

TC Energy noted that their outlook was largely unchanged with their CEO Russ Girling commenting on their Friday afternoon earnings call that “with approximately 95% of our comparable EBITDA coming from regulated or long-term contracted assets, we are largely insulated from the volatility associated with volume throughput and the commodity prices that are being experienced by many others. Aside from the impact of normal maintenance activities and seasonal factors to date, we have not seen any meaningful change in the utilization of our assets, which further reinforces their critical nature to North America.”

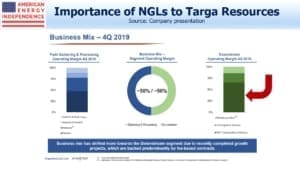

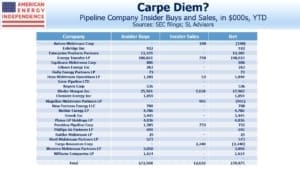

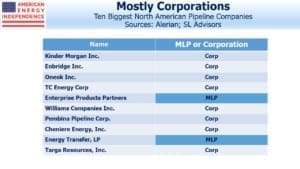

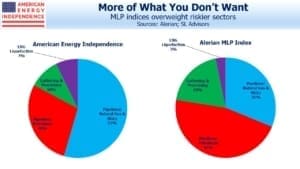

Large midstream companies are generally maintaining dividends and where 2020 results are guided lower, cuts in growth spending more than offset (see Pipeline Payouts Holding Up). In the 2014-16 downturn, MLP distribution cuts were widespread. The payout on the Alerian MLP ETF (AMLP) is the lowest in its history, and 36% below its level of 2016. In a familiar story, 21 MLPs have recently cut distributions. EPD and MMP are an exception to this pattern, which puts them in the company of large pipeline corporations. The components of the broad-based American Energy Independence Index (which is 80% corporations) currently yield 10.5%.

We are invested in all all the names mentioned above.