None of us will forget the past couple of weeks. Investors and money managers are grappling with collapsing markets, working remotely and the challenges of ever stricter controls on our movement.

Below we’ll highlight some information that investors may have missed, combined with what we’ve learned from multiple conversations.

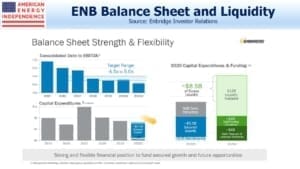

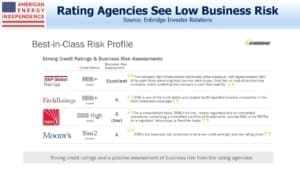

Pipeline companies that said anything publicly were reassuring. Ten days ago and well into the market crisis, Oneok (OKE) cut growth capex by 20% and reaffirmed 2020 guidance. On Monday Enbridge (ENB) provided a reassuring assessment of their business prospects (see Enbridge Fireside Chat). Since then, Pembina (PBA) cut growth capex by 40% and reaffirmed EBITDA guidance, and Enterprise Products Partners (EPD) declared their normal quarterly distribution. Targa Resources (TRGP) slashed their distribution by 90% which was no great surprise, and lowered growth capex by 30%. Williams Companies (WMB) announced a poison pill lasting a year, to fend off any unscrupulous buyer seeking to acquire the company at a rock-bottom price.

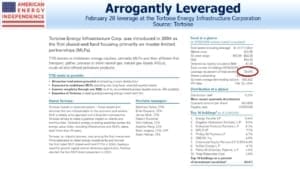

MLP closed end funds and leveraged MLP exchange traded notes were almost wiped out by forced develeraging (see The Virus Infecting MLPs). Incredibly, many of these funds, run by well-known MLP managers such as Tortoise and Kayne Anderson, were leveraged up to 40% as recently as the end of February. In looking at the size of these funds and volume figures, it’s plausible that they were a significant portion of the selling in this sector earlier last week. While coronavirus was unpredictable, the arrogance of these fund managers in maintaining maximum leverage exposes a complete absence of risk management at their firms, and others like them. They have caused a steeper fall than would have happened otherwise. Their NAVs have shrunk far enough that they’re now too small to have much impact going forward.

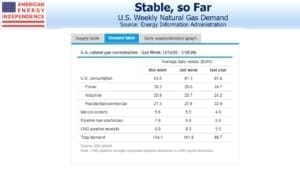

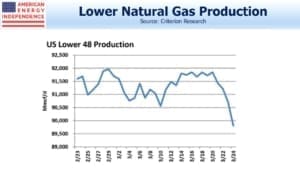

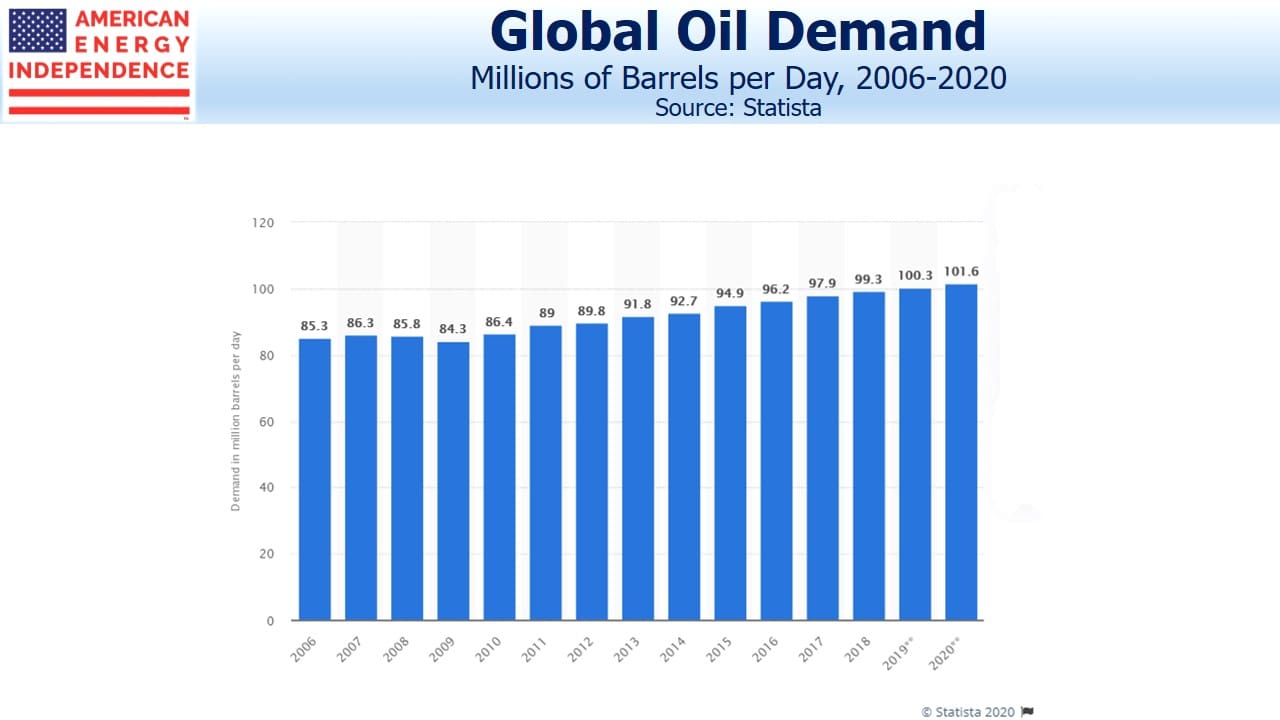

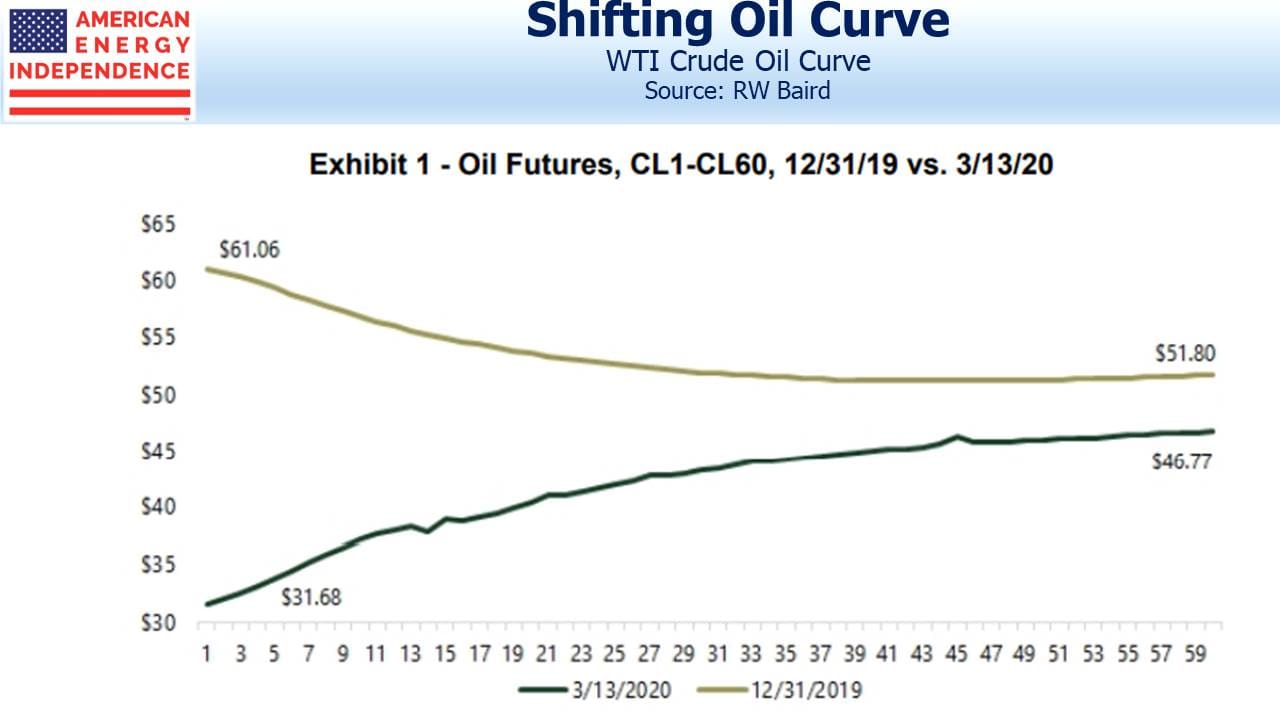

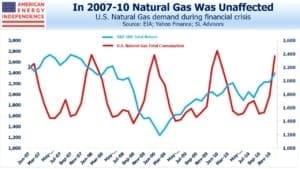

Entering 2020, midstream energy infrastructure was set for a doubling of Free Cash Flow (FCF) (see Updating the Coming Pipeline Cash Gusher). The analysis was based on guidance all provided prior to the coronavirus outbreak, although recent updates have been encouraging. We had estimated 2020 growth capex at $37BN for the components of the American Energy Independence Index (AEITR). Average reductions of 20% would free up $7BN in FCF, and since we’re almost through 1Q20 they represent a bigger cut in previously planned spending for the remainder of 2020. We see the industry as broadly in pretty good shape to withstand the type of drop in energy demand that seems likely.

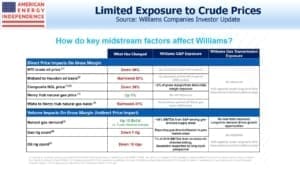

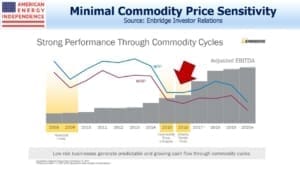

Making forecasts over the next year or two is reliant on the path that the virus takes, the success we have in defeating it and resolving the economic damage. In countless conversations with investors this week, we have stressed that while we can offer our insights on the sector we cover, we won’t pretend to be virus experts. We have a constructive view that the severe health threat posed by the virus will be met within a few months. Someone with a more negative view might infer, say, a severe drop in domestic energy consumption for a couple of years, and that would alter the outlook for pipelines. Our portfolio companies are >75% investment grade with customers that are around 80% investment grade. Exposure to crude oil, and gathering and processing networks, is small because stocks with that type of exposure have already fallen so far.

We have found investors are mostly sitting tight, regarding the drop as too sudden and sharp to warrant a hasty response. There are investors with cash looking for a good entry point. And to bring home the widespread economic damage, we’ve spoken to clients who anticipate providing financial support to children and other family members who have lost their jobs.

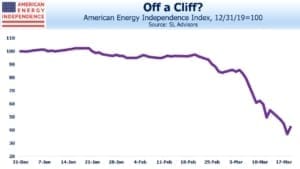

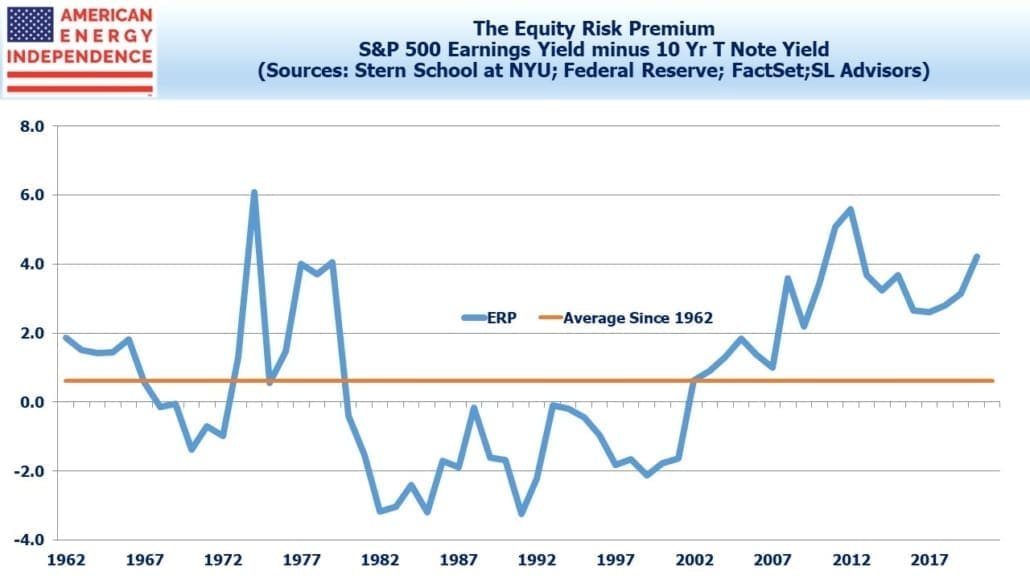

The AEITR is down 55.6% for the year, and the S&P500 is down 28.6%. From October 9, 2007 to March 6, 2009, the S&P500 fell 56%. On Friday, it was 32% off its high of February 19th, a very long month ago.

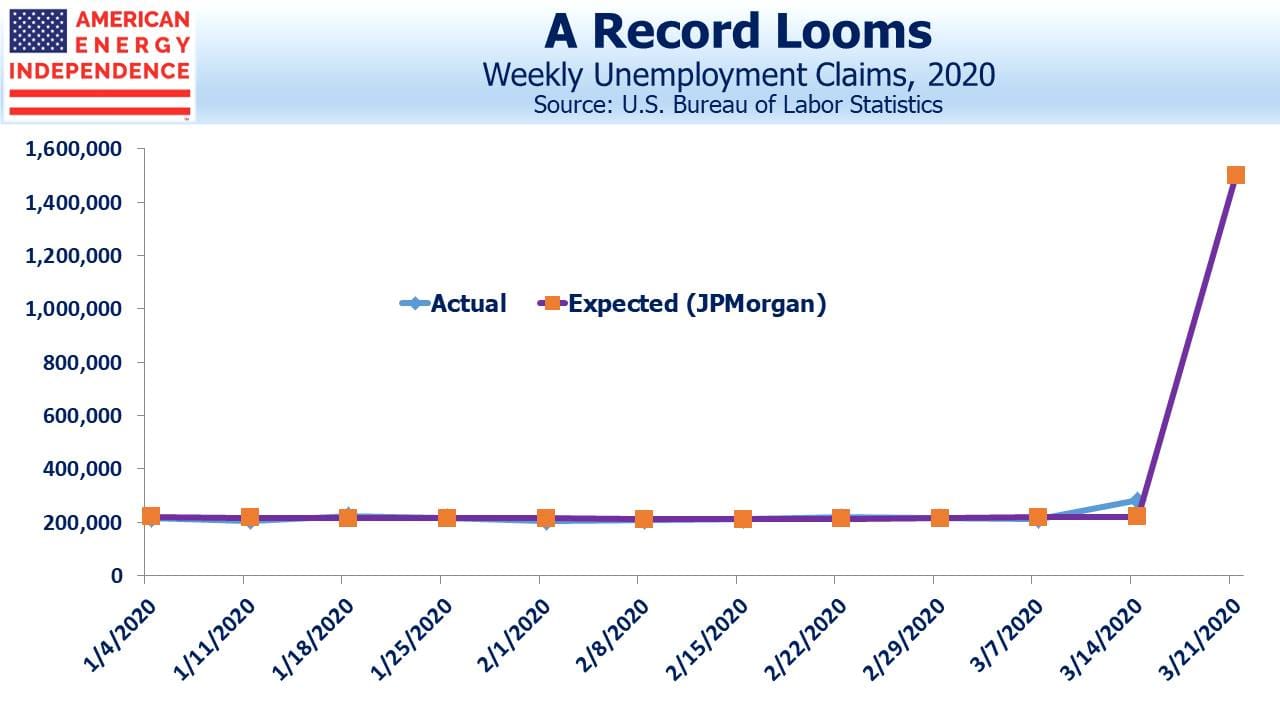

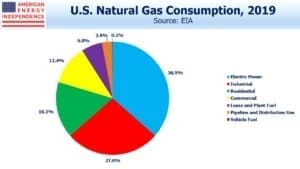

Finally, this chart caught our attention.

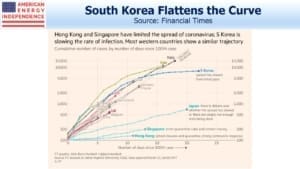

Outcomes vary widely by country. South Korea stands out as handling the health crisis as well as anybody. Germany is carrying out 160,000 tests a week, has 19K cases and 67 deaths (as of Friday 4:30pm NY time). The 0.3% fatality rate is still higher than flu, but contrasts with Italy’s 4,032 deaths and 8.6% fatality rate. Although there can be many reasons for the difference, infection numbers may be low depending on testing availability, while deaths are probably counted correctly. So Germany’s figures are likely more representative. U.S. infection numbers will increase as testing becomes more widespread. But if the curve eventually flattens to look more like South Korea, that would be the best news we’ve had in a while.

We are invested in ENB, EPD, OKE, PBA, TRGP and WMB.