Pipeline Investors Welcome Less Spending

Most energy investors wish the Shale Revolution had never happened. Energy independence was realized through sharply higher oil and gas output. But the promise of similarly bountiful investment returns was not. U.S. E&P executives have overspent and overproduced. Unfortunately, the midstream infrastructure sector too often followed along. Drilling and building infrastructure is in the DNA of many industry executives.

Spending on growth projects is how companies with capital discipline increase their profits. Because so many energy companies, both upstream and midstream, have been poor at capital allocation, investors now regard growth projects with suspicion. When it comes to growth capex, less is more.

In the years preceding the Shale Revolution, midstream companies (then predominantly MLPs), weren’t investing heavily in new projects. There wasn’t the need. America was obtaining its oil and gas from roughly the same places in the same amounts year after year. Pipelines were about running a toll-model: charging fees for use of infrastructure, raising prices annually, spending on maintenance capex and finding productivity improvements to boost profits.

That’s the pipeline business that attracted older, wealthy, K-1 tolerant income seeking investors. They’ve mostly left, because the industry abandoned the stable distributions they’d s ought in favor of growth. The MLP model has lost favor to the traditional corporation, with its ability to access a far wider set of investors.

The 2014-16 energy downturn, which now seems like a fond memory compared with this year’s rout, saw a fall in growth capex as pipeline companies responded to the collapse in crude prices. But it wasn’t long before spending on new projects recovered along with energy prices, and the industry returned to its new ways. By 2018 the industry was spending more than at the sector’s peak in 2014. Investors were increasingly boycotting energy names as a protest at continued new projects.

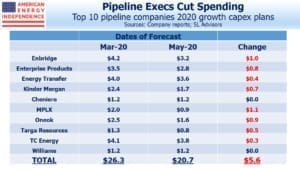

By 2019, pipeline execs who had long complained that the market undervalued their stocks, were at last taking some value-enhancing actions while still lamenting the absence of investor affection. Growth capex was coming down, and the downward path was already expected to continue this year before Coronavirus scrambled everyone’s plans.

Since March, when U.S. economic activity halted in response to the pandemic, the energy business has rapidly altered its plans. Shale production is now expected to exit 2021 at 2.5 Million Barrels per Day (MMB/D) lower than pre-Coronavirus forecasts. Given the sharp decline rates common with shale, caused by the high initial pressure at which its hydrocarbons are released, new wells are constantly required to maintain production. Goldman Sachs estimates that last year 70% of new well capacity was offset by base declines, with only 30% feeding growth in output. As drilling activity plummets, depletion will quickly lower U.S. production.

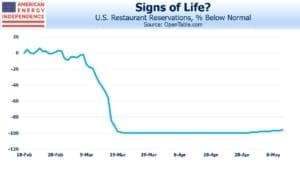

Future energy demand from the transportation sector is highly uncertain. Working remotely, with the daily commute now a memory, has been welcomed by many – with the possible exception of families with small children at home. Many companies are rethinking their use of expensive downtown office space. Cramming all your workers together also exposes a business to a sudden loss of an entire department to illness if an infection spreads. Dispersing your workers may become smart risk management. Client visits and business travel of all kinds may reset permanently lower. Mass transit use remains very low as other forms of travel show signs of recovery. If the perception of crowded subway trains as carrying high risk of infection persists, gasoline use may surge as commuters resort to driving. The energy requirements of moving people are changing.

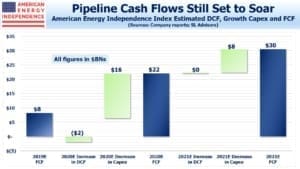

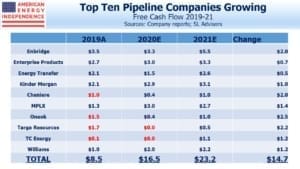

The top five midstream companies have all responded to all this by reducing 2020-22 spending by almost $3BN a year. If This 16% reduction applies across the industry, growth spending will be close to the $32BN low of 2016. By next year it’ll be $5BN below that.

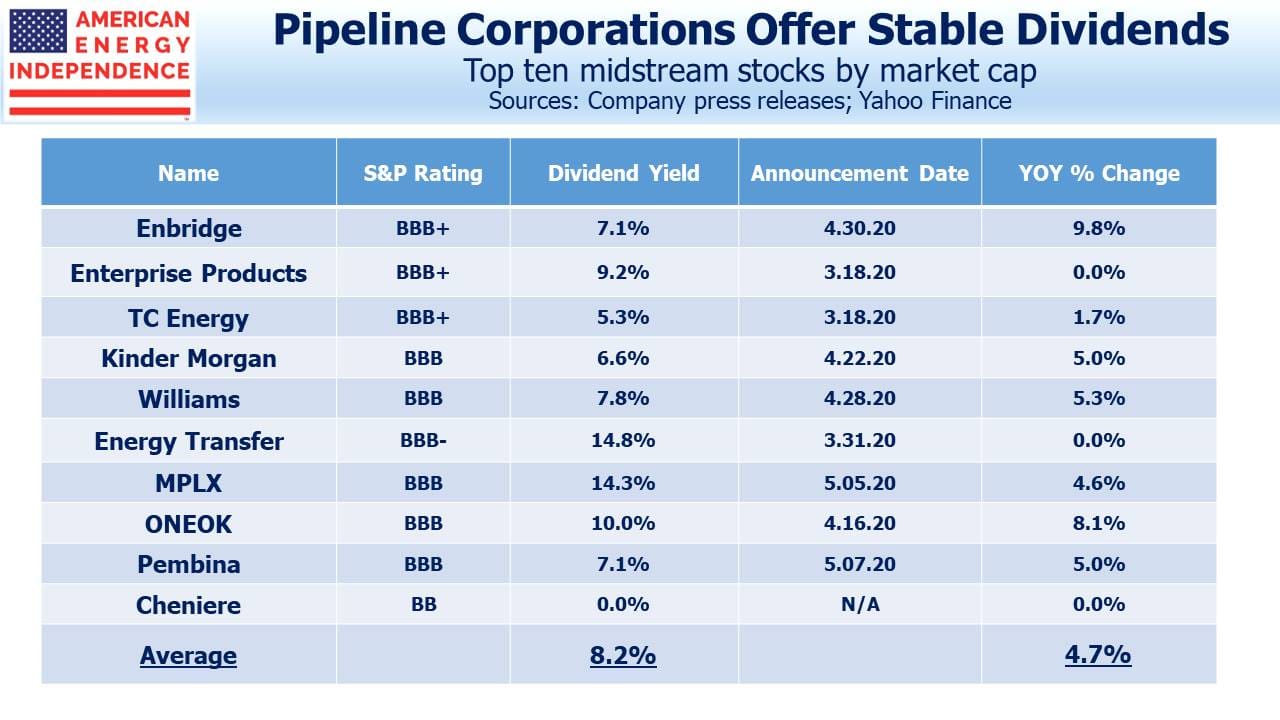

Some companies have been disciplined about requiring investments to generate a risk-adjusted return above their cost of capital. The Canadians are prominent in this group. But many have not, which is why falling growth capex is likely to be welcomed by investors. As midstream companies are faced with fewer uses for the cash they generate, investor-friendly uses such as dividend hikes and debt reduction will benefit.

It’s probably no coincidence that the recovery in pipeline stocks has coincided with more modest growth spending. By lowering the need for spending on new projects, the pandemic just might provide investors with long overdue strong returns.