Pipelines Offer Protection From European Conflict And The Fed

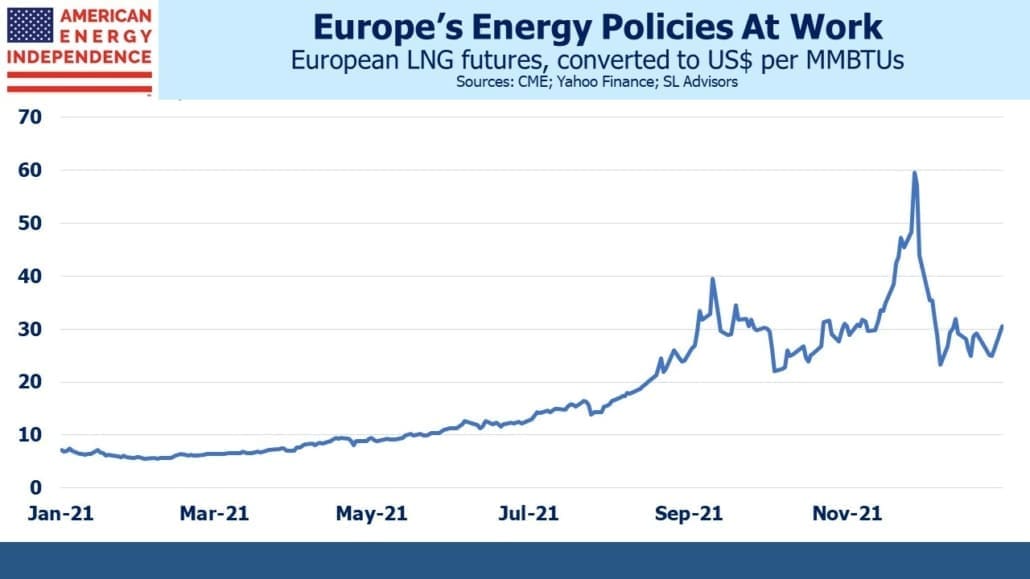

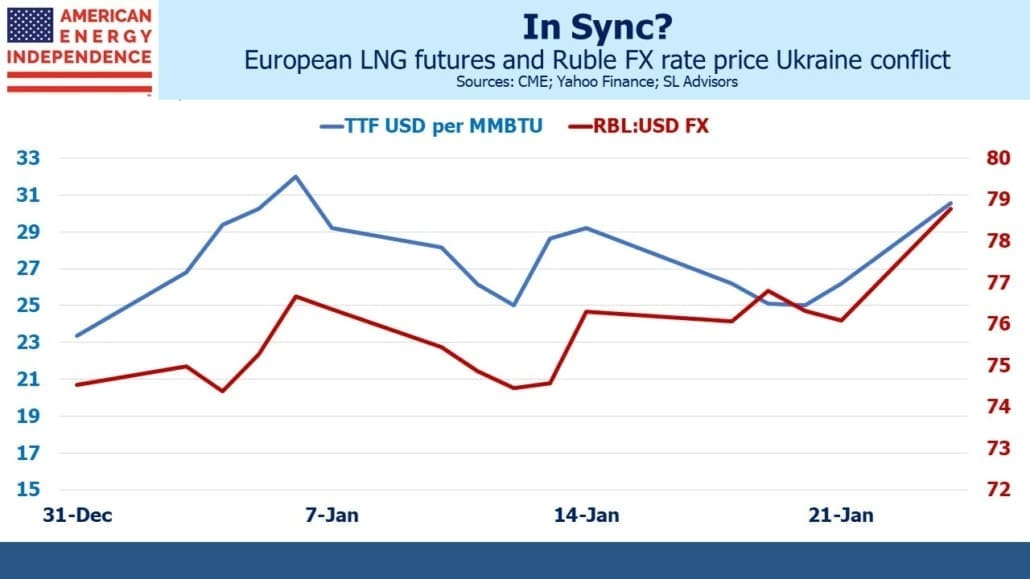

Friday afternoon’s warning from the White House that a Russian invasion of Ukraine could come at any time did at least distract attention from Thursday’s CPI. Energy stocks rose while the S&P500 fell – a welcome negative correlation.

Bonds also recouped their losses from the prior day. Over several decades the bond market’s sensitivity to rising energy prices has evolved. In 1990 when Iraq invaded Kuwait, threatening to cut supply of oil to the west, bond yields rose sharply. The memories of 1970s inflation caused by OPEC raising prices was still fresh.

At other times, rising crude has been regarded as a tax hike, since it does represent a wealth transfer from oil consumers to producers. The Shale Revolution altered US sensitivity to oil prices by increasing the portion of the economy that benefits when they’re high. Your blogger has to restrain his glee when friends complain about the price at the gas pump or how much they’re spending on heating oil. During the Covid-induced collapse in the energy sector in early 2020, cheap gasoline provided scant solace for depressed portfolios. We look forward to crude oil continuing its march higher.

Friday saw higher prices for bonds, crude and pipelines, as the rest of the market feared European conflict will hurt growth and sought refuge in energy.

The midstream sector’s strong performance does highlight its resilience to geopolitical risk. Enbridge, North America’s biggest pipeline company, reported earnings on Friday. Enbridge has no assets outside North America, a welcome protection from any global disruption.

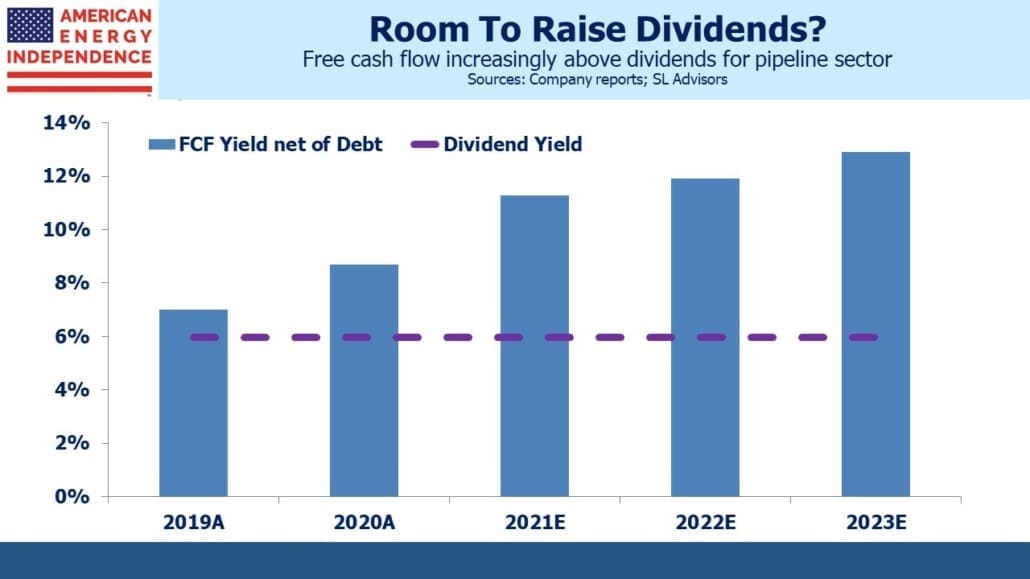

Pipeline pricing is often tightly regulated, to prevent gouging of customers. A substantial portion of the industry sets tariffs based on the PPI. Last month the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC) set the pricing index for the next five years as PPI-0.21%.

Inflation as measured by the PPI Final Demand Goods, the index used by FERC, was 13.6% last year.

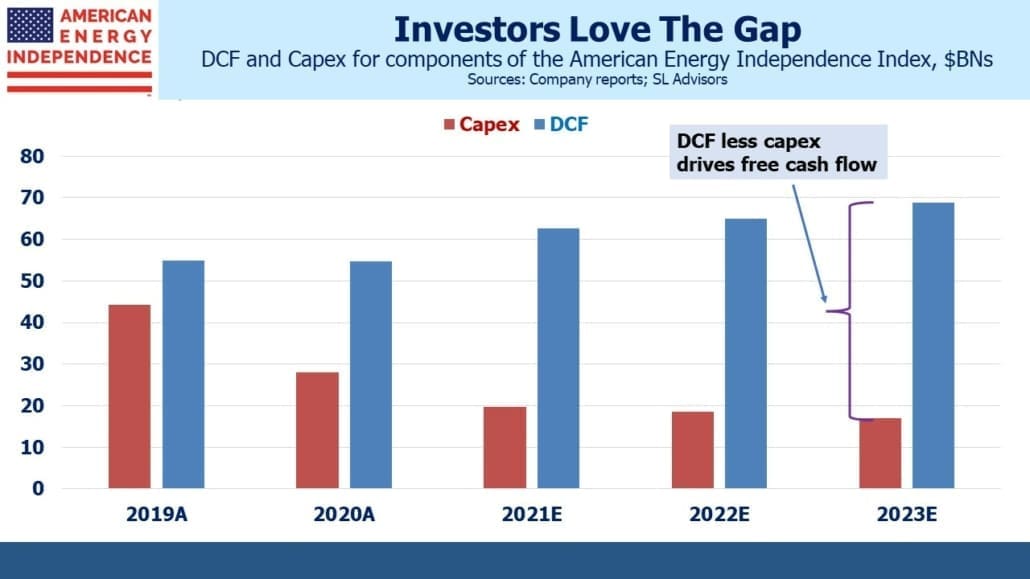

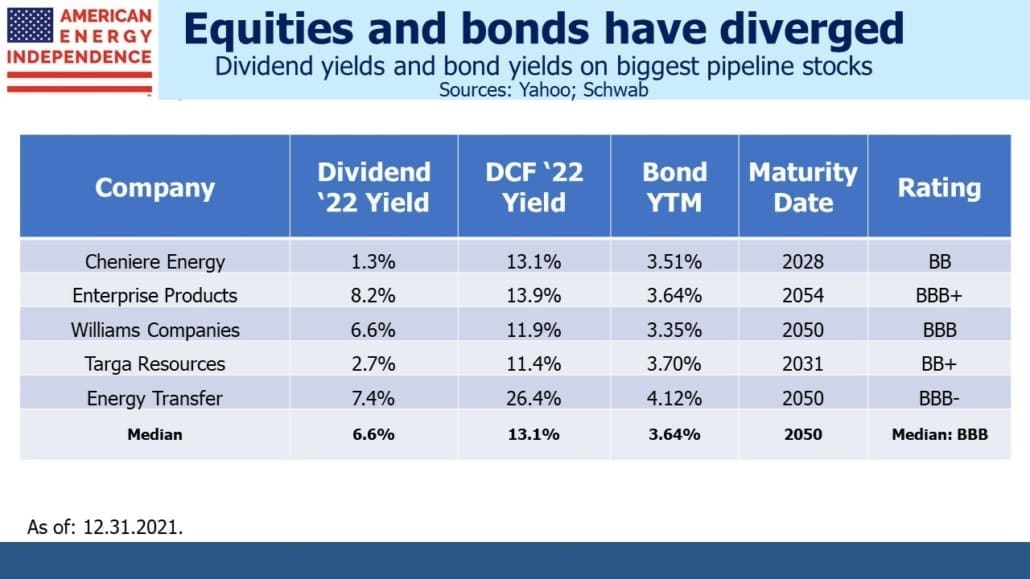

This built-in protection against inflation used to receive more attention. Prior to 2014, before the Shale Revolution had led to some dubious capital allocation decisions, MLPs (since that’s mostly where pipelines were housed back then) attracted investors because of their stable yields that came with built-in price escalators.

The tumult of the last few years has not altered this feature, even though it is rarely on the list of reasons investors cite when making an allocation. But over the next several quarters, expect to see increased mention about Cost of service (CoS) adjustments to pipeline tariffs.

Enbridge, to cite one example, says that 80% of its EBITDA comes from CoS contracts. In August we noted that Wells Fargo estimated a 3% lift to sector EBITDA from PPI escalators (see Pipelines Still Linked With Inflation). This was based on a 2021 PPI estimate of 5.5%, less than half the actual result.

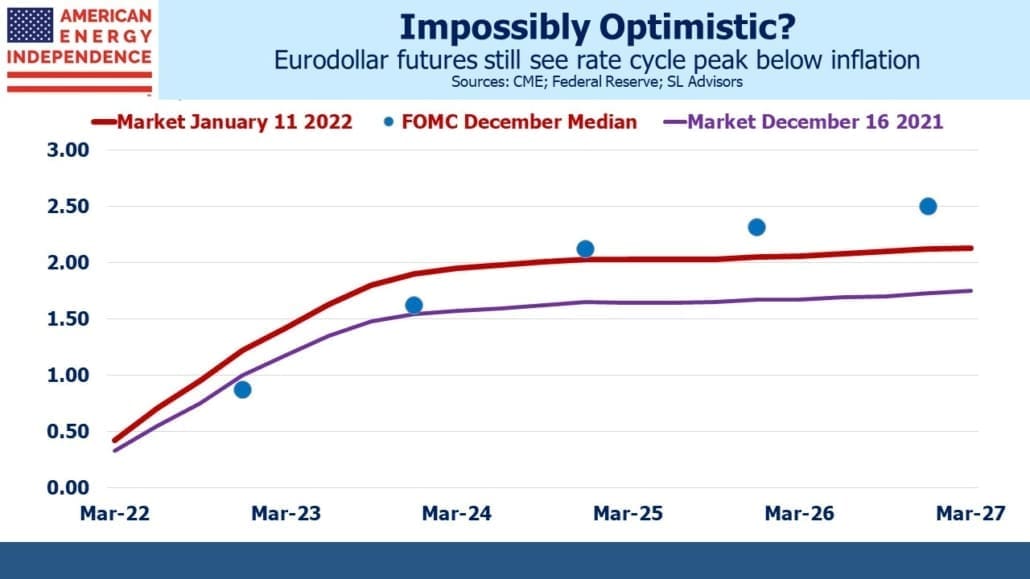

What is becoming clear is that when the FOMC reinterpreted their dual mandate of maximum employment with stable prices in 2019, they made a subtle but important shift in favor of full employment at the risk of elevated inflation. Although it seems surreal given last week’s CPI release, three years ago they were concerned at the tendency of inflation to come in below their 2% target, and the constraint this placed on monetary policy to be stimulative without resorting to negative nominal rates.

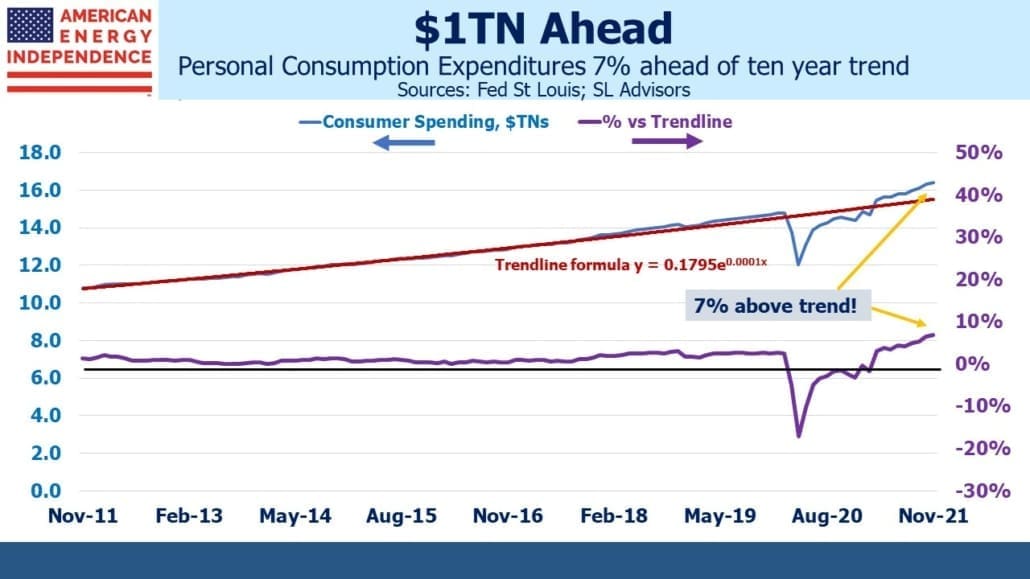

Within six months Covid stopped the economy dead in its tracks, and Congress unleashed enormous fiscal stimulus through early 2021. The Fed’s prolonged monetary stimulus, synchronized with $TNs of debt-financed spending, reflected their new bias towards employment and willingness to risk inflation.

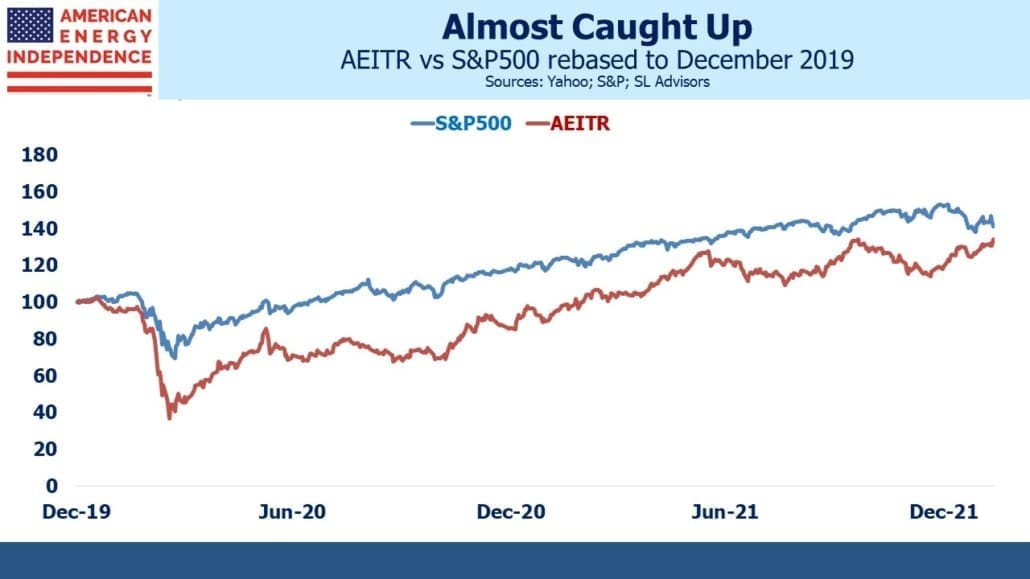

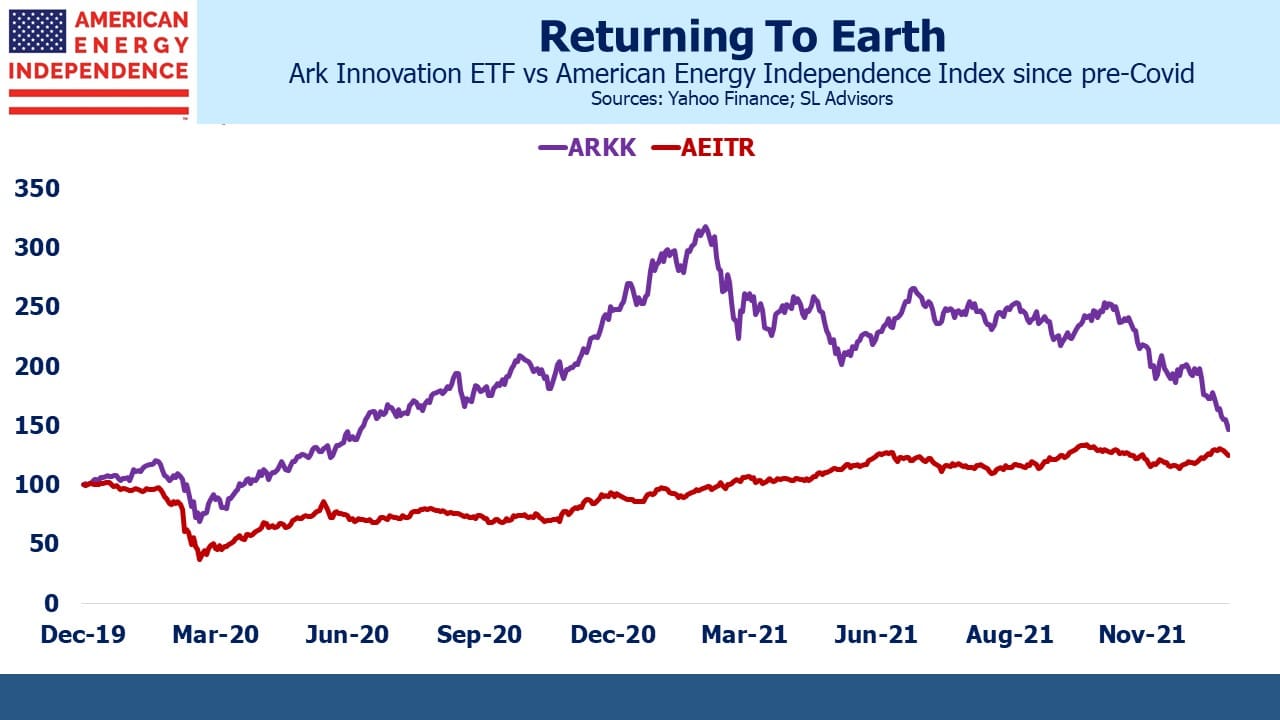

Following a near-death experience in the early months of Covid, the pipeline sector has been steadily closing the performance gap with the S&P500. On Friday the broad-based American Energy Independence Index (AEITR) recorded another good day, beating the S&P500 by 4.7%. It’s within easy reach of being ahead of the S&P500 from the end of 2019, wiping out the entire Covid-related period of underperformance.

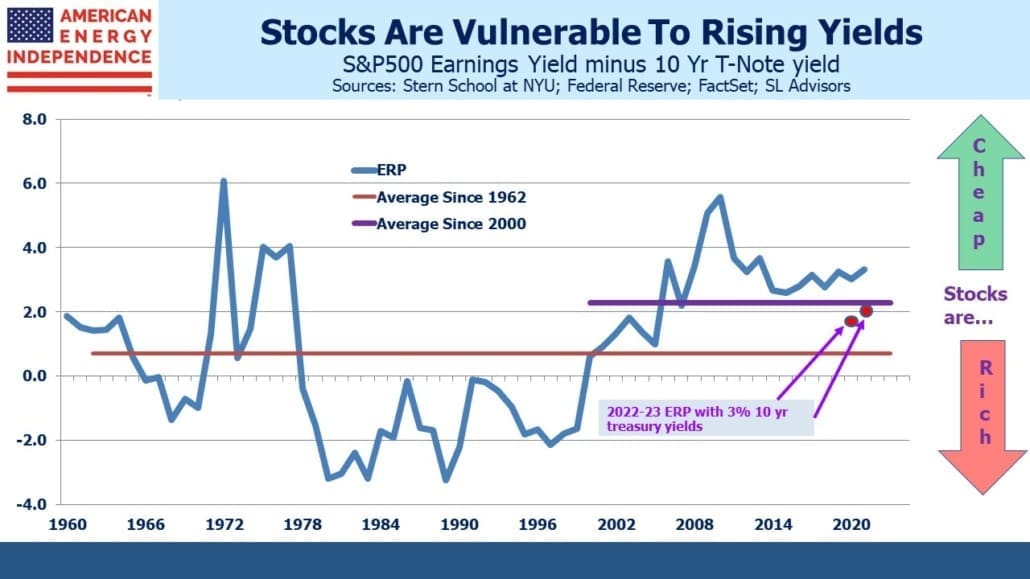

Demand for inflation protection remains strong. Treasury Inflation Protected securities (TIPs) are an example – real yields (i.e. after inflation) are still negative. Big investors are starting to adjust their long term inflation expectations. For example, Blackrock expects inflation to average 3% over the next three years, and five year TIPs are priced for 2.8%. As Americans come to accept that the days of 2% inflation are behind us, it’ll be increasingly difficult for the Fed to bring it back down.

The demand for real assets such a midstream energy infrastructure is driven in part by investors who want protection against the Fed’s new tolerance for a little faster inflation. 3% over the long run is a safer bet than 2%.

We have three funds that seek to profit from this environment:

Energy Mutual Fund Energy ETF Real Assets FundPlease see important Legal Disclosures.