Natural Gas To Remain Top Energy Source For Decades

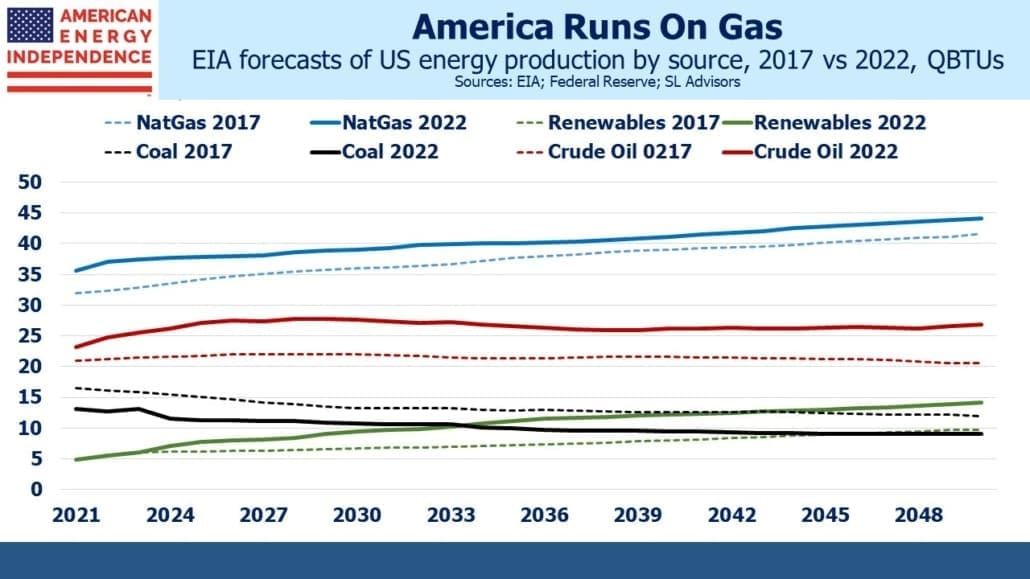

Last week the US Energy Information Administration (EIA) published their 2022 Annual Energy Outlook. Solar and wind output are expected to grow at 4% pa, reaching 12% of our total energy production by 2050, triple their share today. This is an impressive growth rate, although less than the media coverage of renewables would suggest. It’s higher than in the EIA’s 2017 annual outlook, which looked for solar and wind to have a 9% market share by 2050.

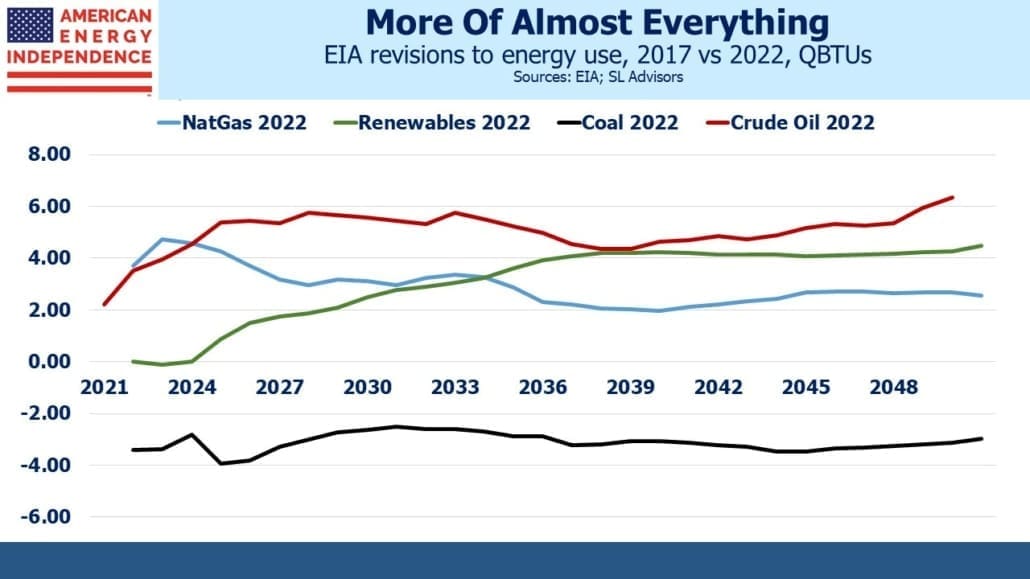

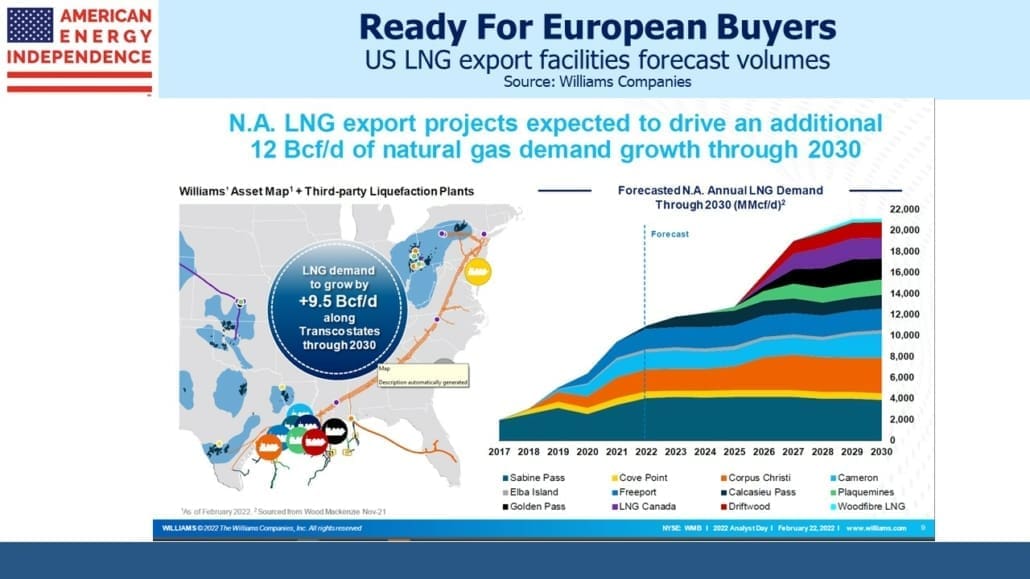

In other revisions, the EIA has also boosted its forecast of natural gas production, which is now expected to grow by 8 Quadrillion BTUs (QBTUs). This puts 2050 production at the equivalent of 121 Billion Cubic Feet per day (BCF/D) versus a forecast of 89 BCF/D for 2022.

Many will be surprised to learn that the energy equivalent increase in natural gas production through 2050 is close to the increase from solar and wind (9 QBTUs). This reflects cheap natural gas, the slow pace of energy transitions and continued growth in domestic energy consumption, which is expected to increase by 7 QBTUs, from 99 to 106. In effect solar and wind will do a little more than cover increased demand.

Another surprise will be the revisions to crude oil production. Over the past five years, the EIA has boosted its 2050 forecast of US oil production by the equivalent of almost 3 million barrels per day. This is more than revisions to solar/wind, or natural gas. Coal is the one area where they’ve lowered expected production.

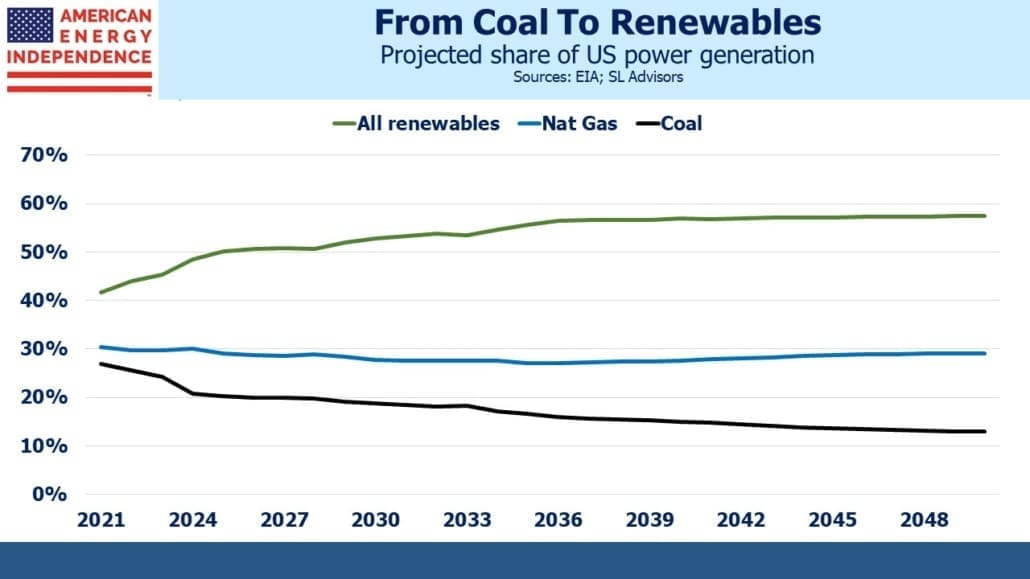

There are other surprising trends. The non-fossil fuel share of electricity production is expected to increase relatively slowly through 2050, from 42% to 58%. This adds back hydropower and nuclear, both sectors unlikely to grow much. The best locations for hydropower were identified and used long ago, while nuclear plants face debilitating opposition. There are signs climate extremists in Europe are becoming more amenable to nuclear, a welcome sign of pragmatism versus the purist view that requires running everything with solar and windmills.

The natural gas share of power generation is not expected to change much – from 30% to 29%. Coal will absorb most of the losses, representing the most realistic path to reducing emissions. By contrast, Germany recently brought forward the deadline by which they plan to reach 100% renewable power, from 2040 to 2035. The US is on track to reach 56% by then after which little change is forecast.

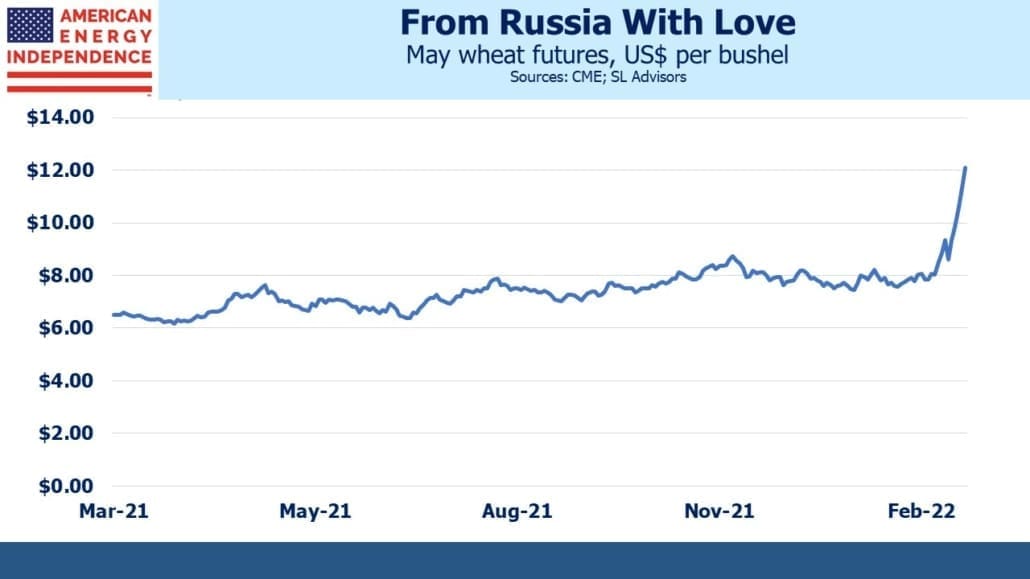

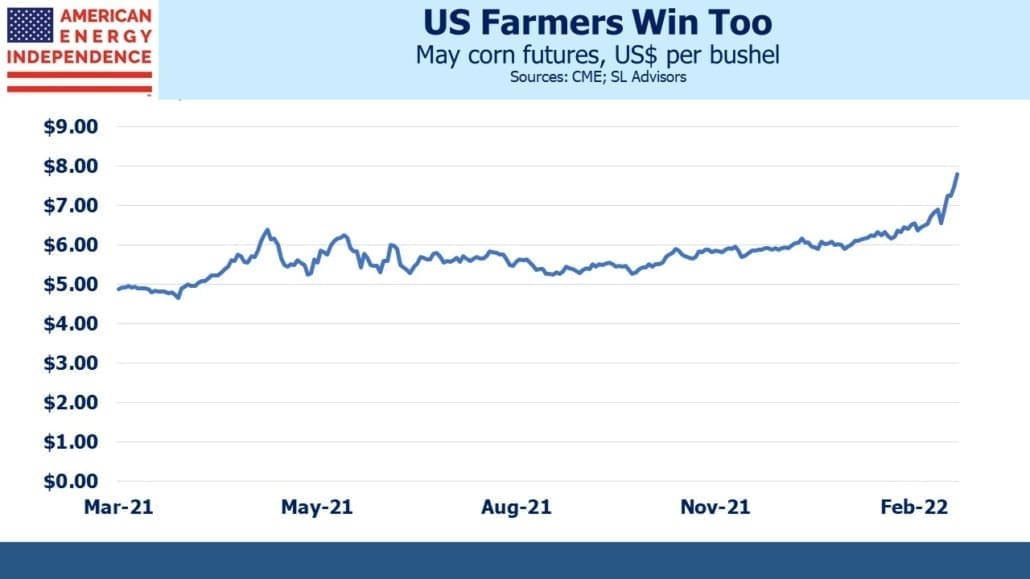

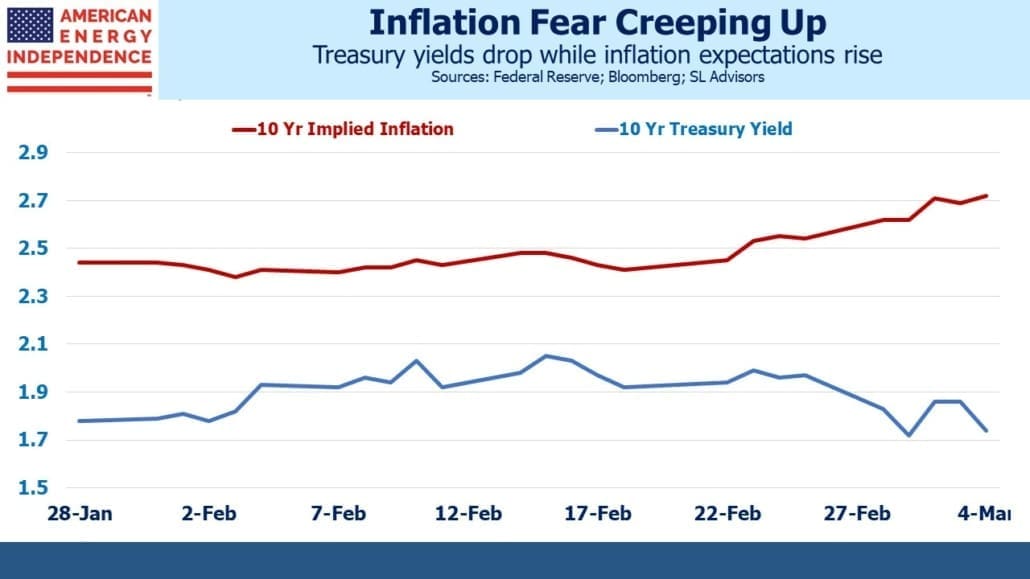

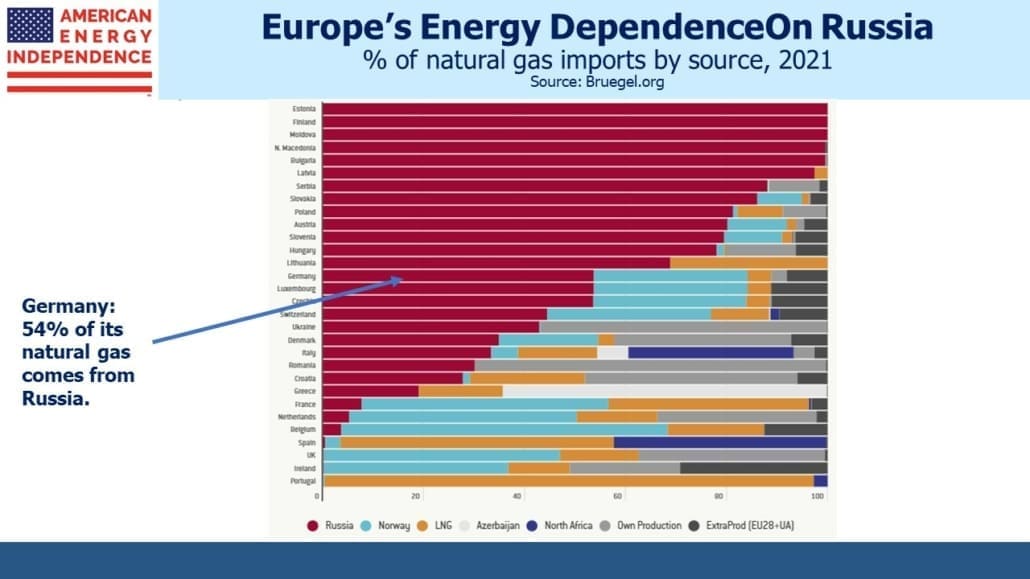

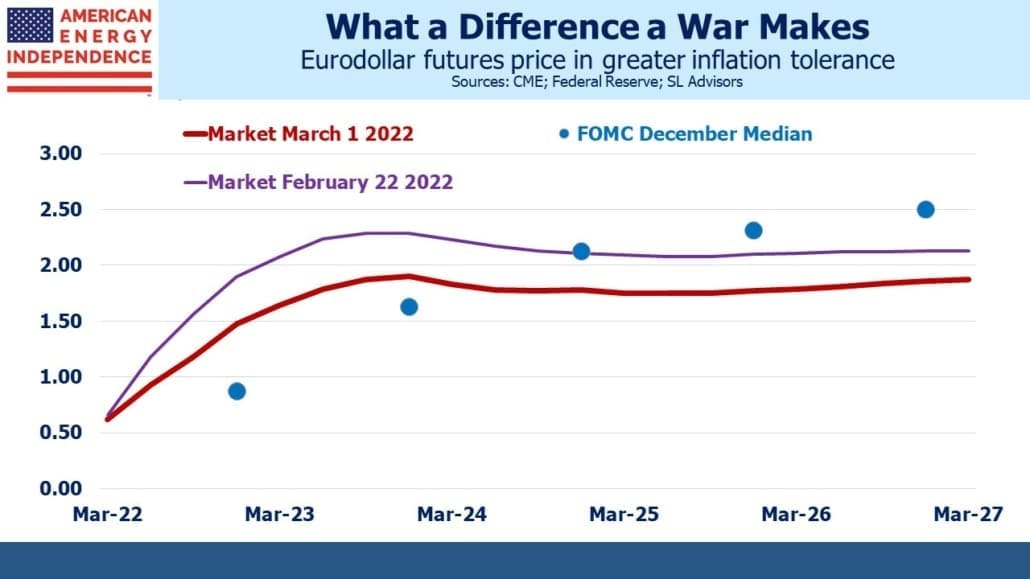

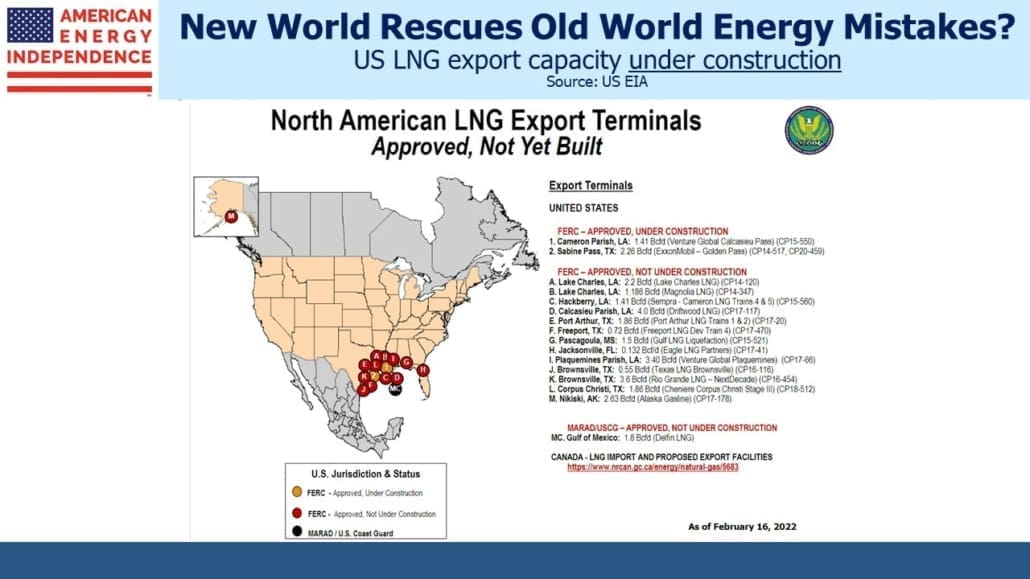

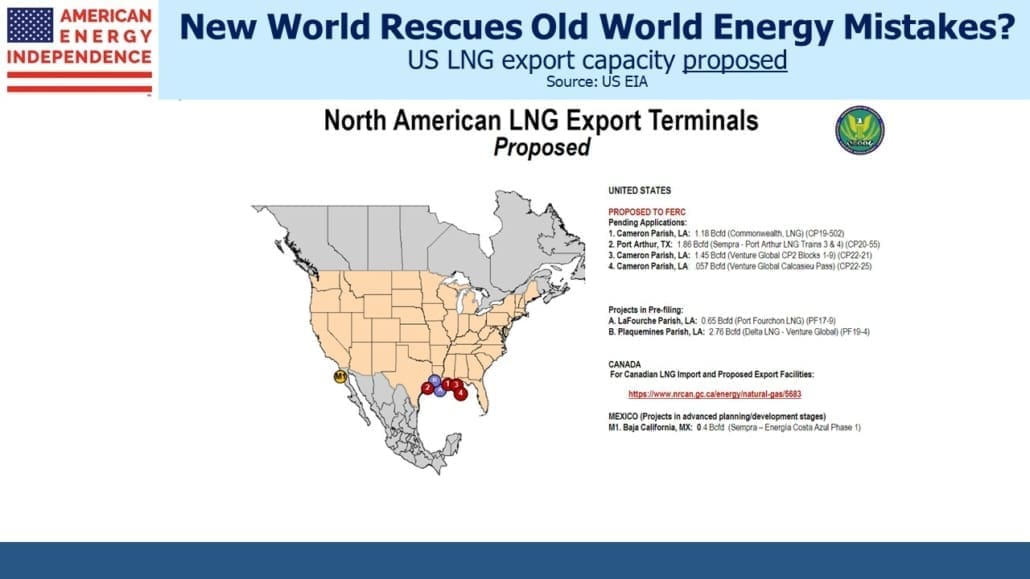

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has suddenly made Europeans more aware of energy security. Renewable power is almost always domestic, so increasing this makes sense on top of buying more LNG from other countries including the US. But so far Germany’s headlong rush towards windpower hasn’t been something to emulate. We’re fortunate that the US isn’t moving at the same speed. It would only serve to accommodate China’s persistently increasing emissions. Russia isn’t helping much either.

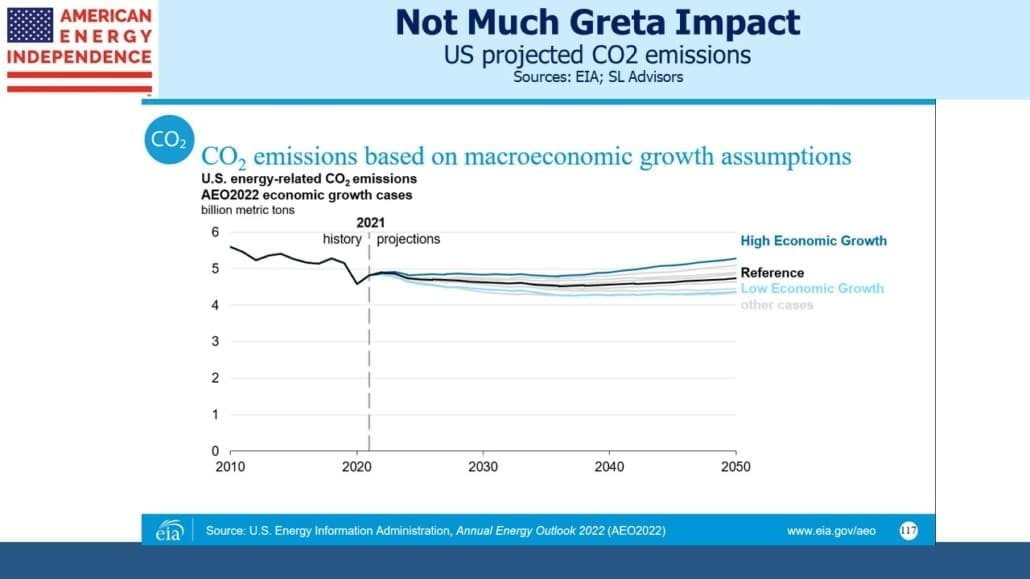

The EIA’s outlook on emissions shows generally steady state for the next three decades – a slight dip through 2035 followed by a modest increase. High oil prices and slower growth might cause a bigger reduction – a combination we are likely to experience based on recent events. But until voters accept higher-priced energy as necessary to reduce emissions, we’re unlikely to see much change.

Neither political party has offered appealing solutions – Progressives implausibly want the whole world to run on solar and windmills. Conservatives see little appetite among voters to pay more to reduce emissions. US states play a big role, which has led to more modest steps reflecting popular ambivalence on the issue.

That contrasts with the Administration’s stated goal of cutting CO2 emissions in half by 2030, although they haven’t yet provided any details on how they plan to do that. The infrastructure bill that recently passed included $8BN in funding to establish four hydrogen hubs, which would enable greater use of the clean-burning fuel by the power and industrial sectors. Hydrogen is 2-3X the price of US natural gas, but the right economic incentives would boost its role. The EIA projects almost no hydrogen use even by 2050. Europe is farther ahead because natural gas prices before the Ukraine war made it competitive.

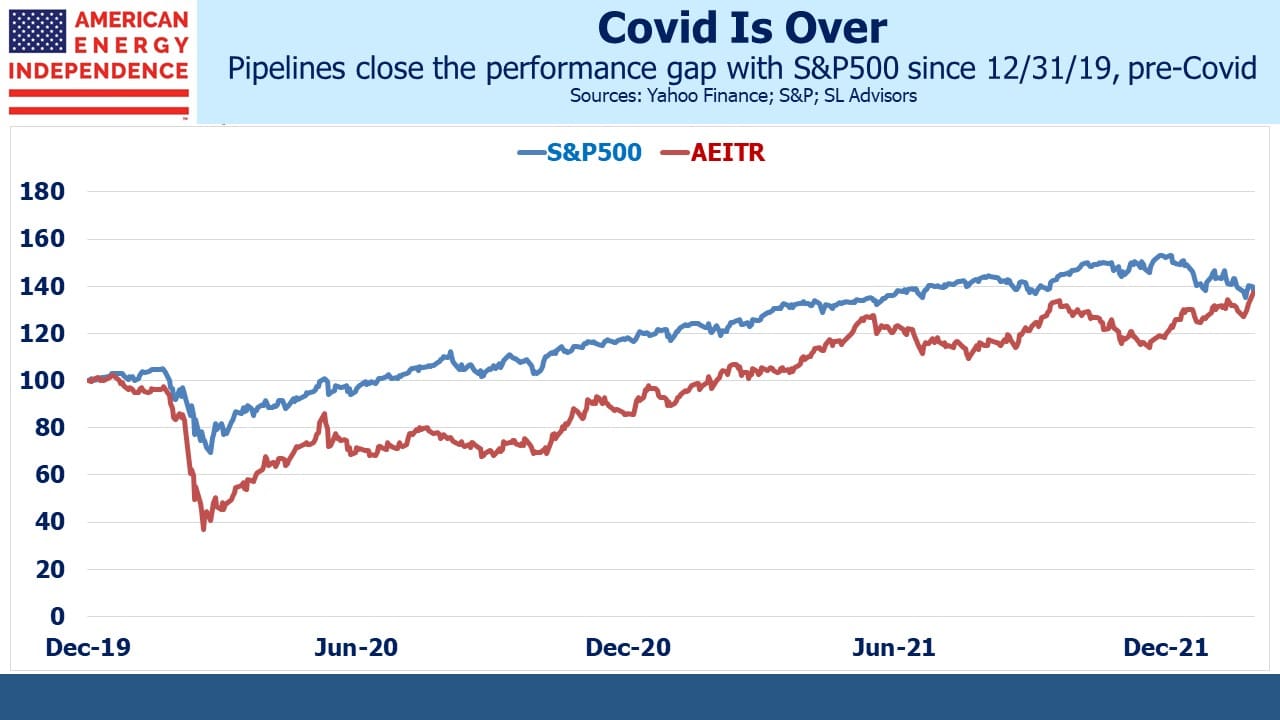

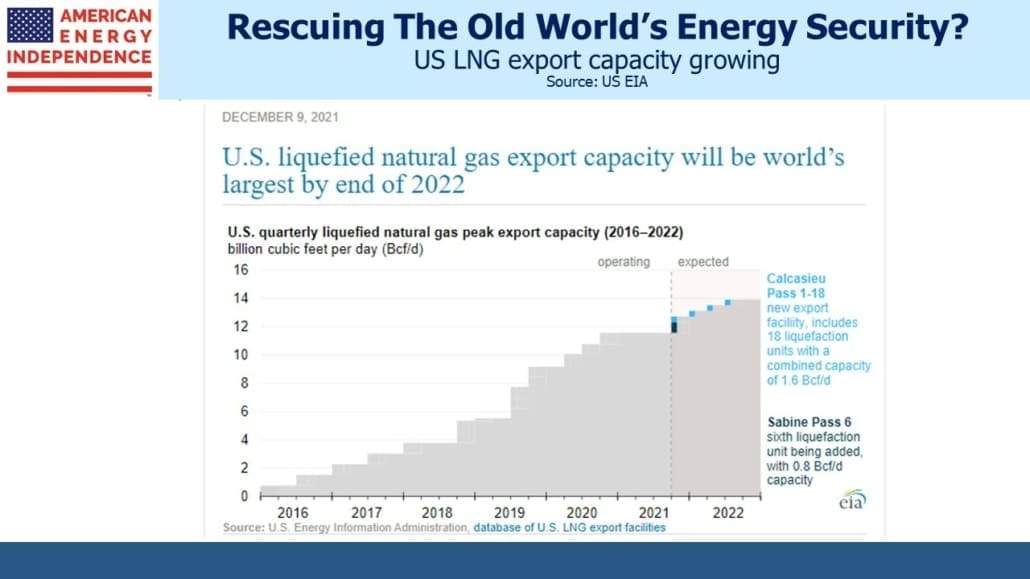

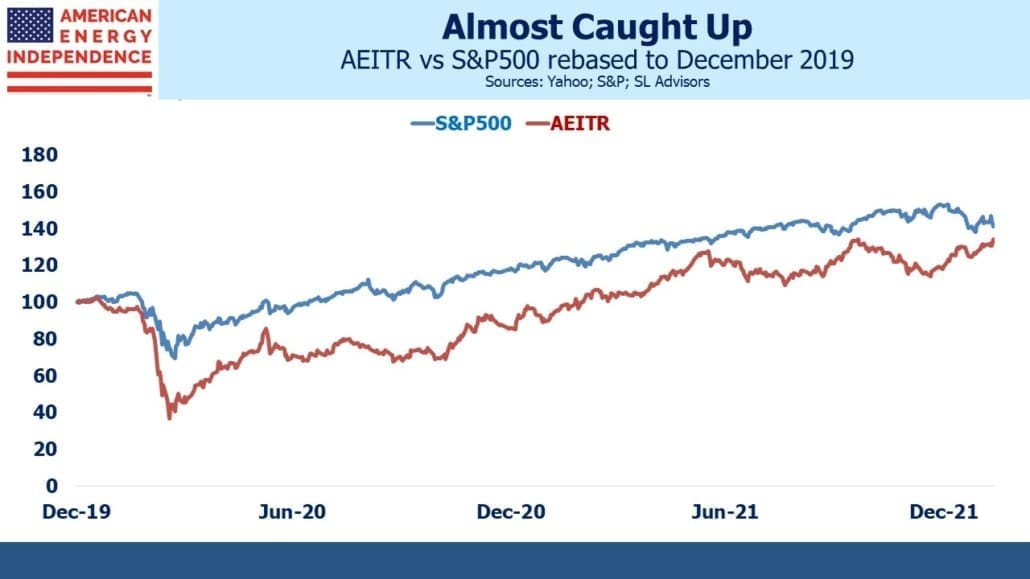

The EIA annual outlook reminds that US natural gas output has a bright future, likely to grow for decades. It’s why we invest in the sector – the economics are more attractive than renewables, helped by the widely-held erroneous belief that fossil fuels are going away. Over the past five years the EIA has revised fossil fuel production up by more than renewables. Europe’s sudden realization that they need to import more LNG isn’t factored into the EIA’s report, prepared as it was before Russia’s invasion.

Investors are starting to recalibrate their expectations, like the EIA.

We have three funds that seek to profit from this environment:

Energy Mutual Fund Energy ETF Real Assets FundPlease see important Legal Disclosures.