The Upside Case For Pipelines – Part 1

The world doesn’t need another “what to expect in 2022” outlook piece. Inboxes are full of them this time of year. Therefore, what follows is part 1 of a two-part look at what could create upside surprises for midstream energy infrastructure. The downside is well understood and was experienced in full force quite recently. On March 18, 2020 the Alerian MLP Index (AMZIX) closed down 67% for the year. The broad-based American Energy Independence Index (AEITR) was marginally better at down 63%. There’s no plausible downside scenario that can beat that for a live ammunition drill. Within 19 months the two indices had rebounded 220% and 264% respectively.

What follows is inspired by Byron Wien’s Ten Surprises. These are upside developments that are plausible but not consensus. This blog post will focus on non-commodity price items – Sunday’s will look at scenarios for higher oil and gas.

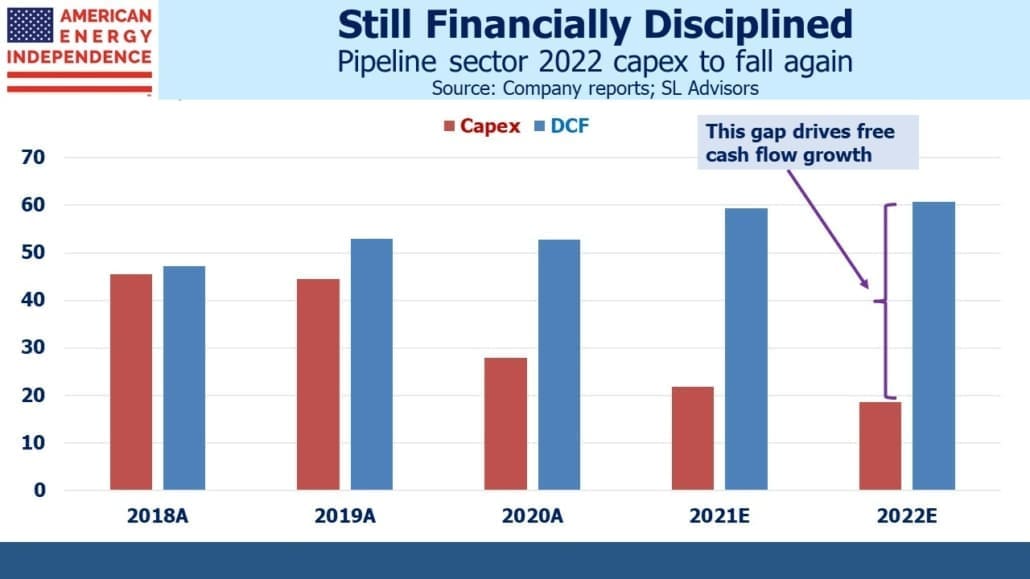

1) Investors become convinced financial discipline will continue

Although growth capex peaked in 2018, the sector continues to be priced as if such prudence will prove temporary. We project that for the companies in our index 2021 spending will be down by more than half from the 2018 peak, and continue lower in 2022. A couple of companies are expected to buck this trend somewhat (Kinder Morgan and Pembina), but generally the direction is down. Lower spending has been the most important factor driving Free Cash Flow (FCF) higher, although rising Distributable Cash Flow (DCF) has also helped.

Although four years of discipline is presumably reflected in the market, we continue to believe that dividend yields above 7% and FCF yields above 11% reflect persistent skepticism, perhaps because of the prior history. This is an industry that long attracted income seeking investors with stable payouts that grew, and modest growth capex. The damage that abandonment of this model and the associated investor base caused still tarnishes its reputation. If the market starts to become convinced this is the new normal, the sector could reprice to the upside.

2) Pragmatism guides the energy transition

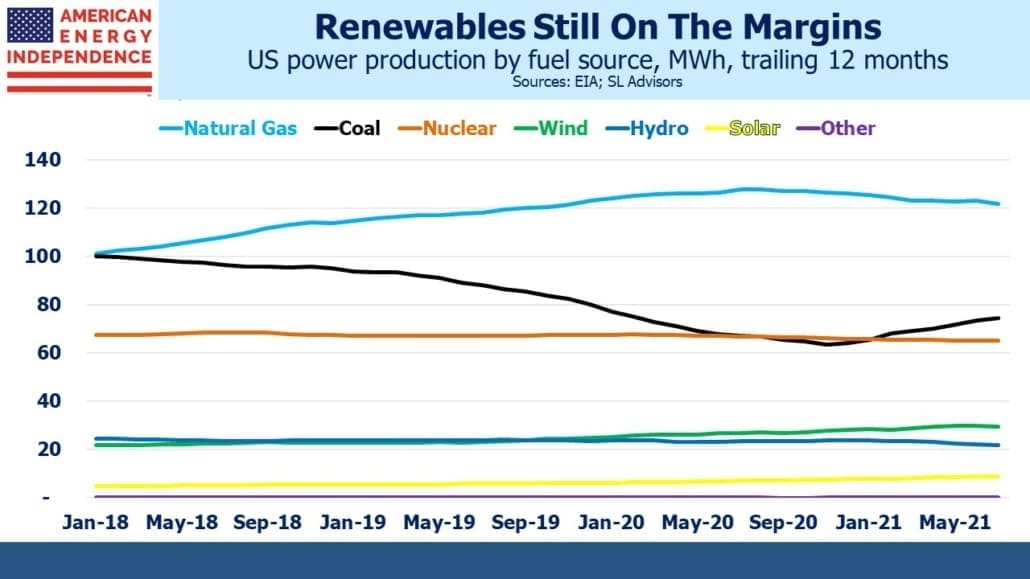

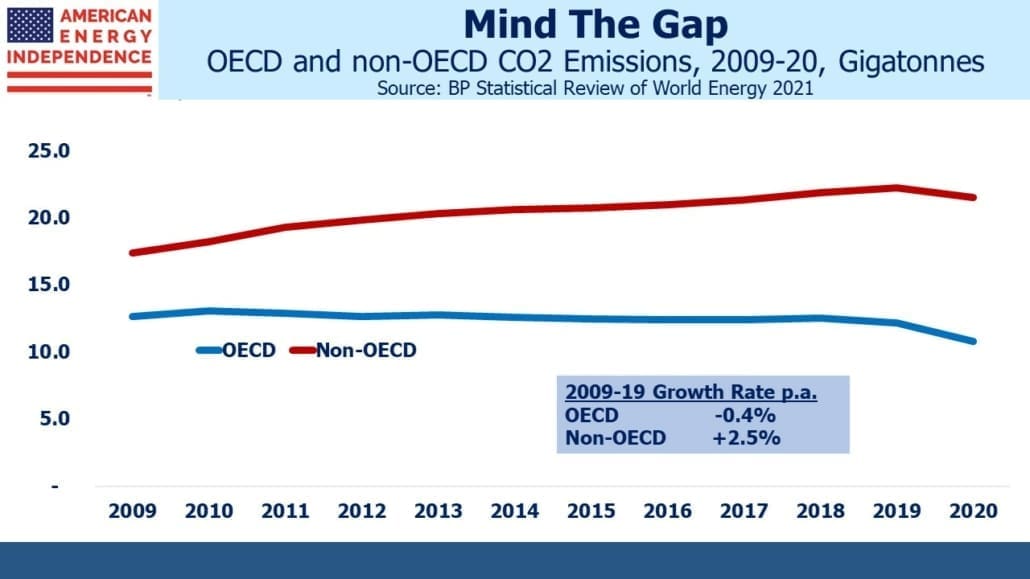

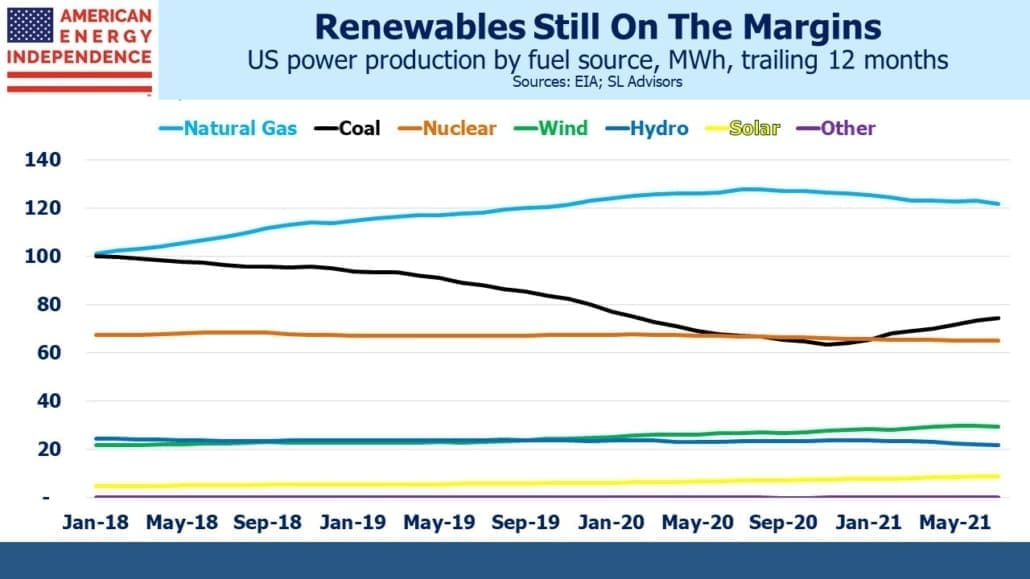

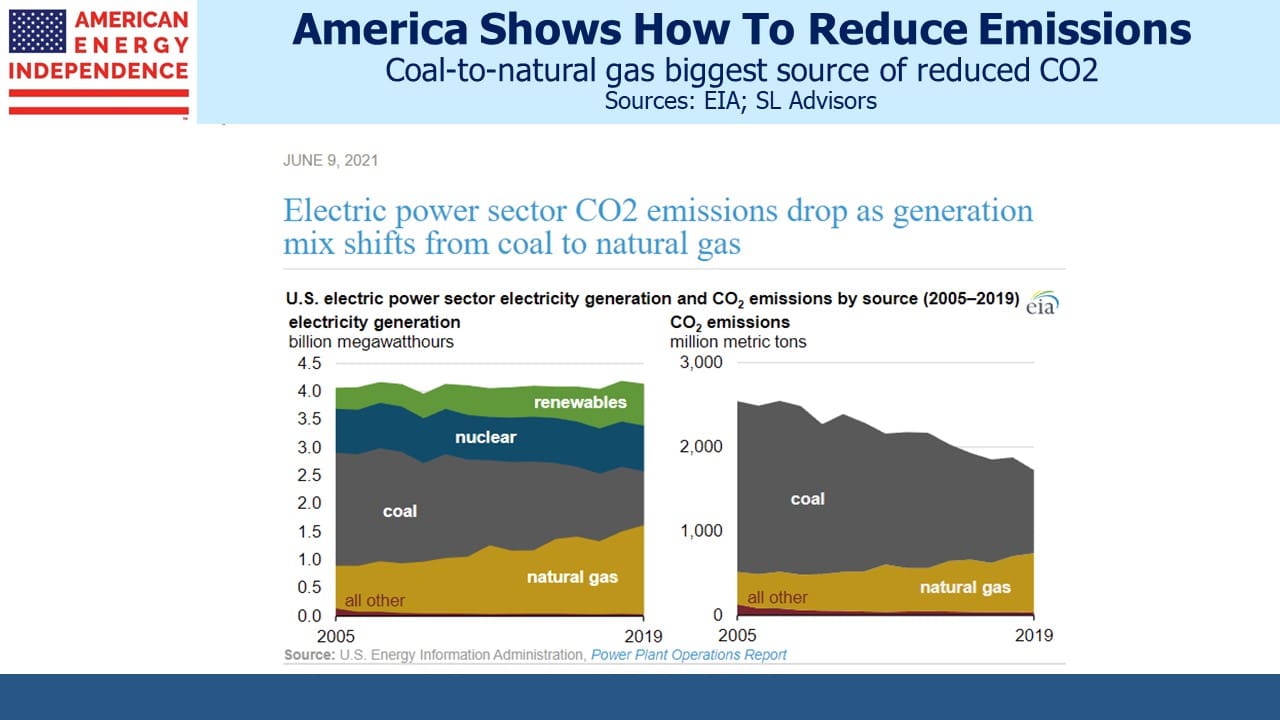

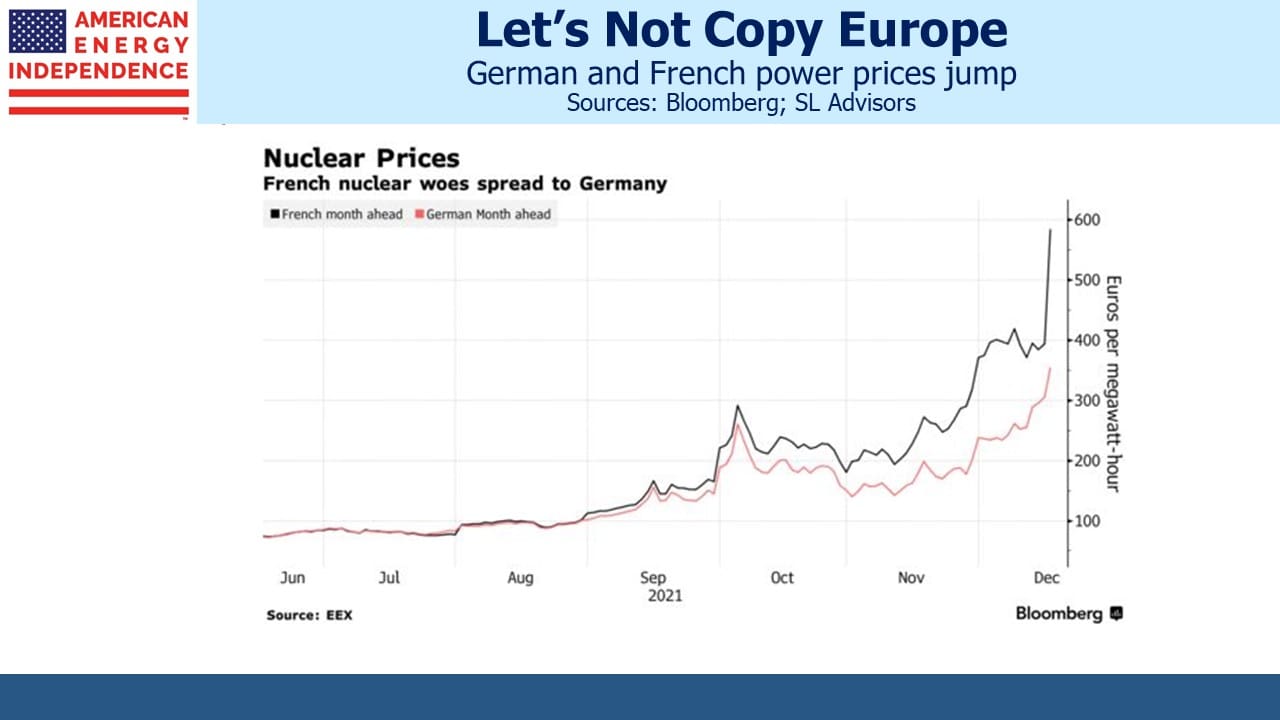

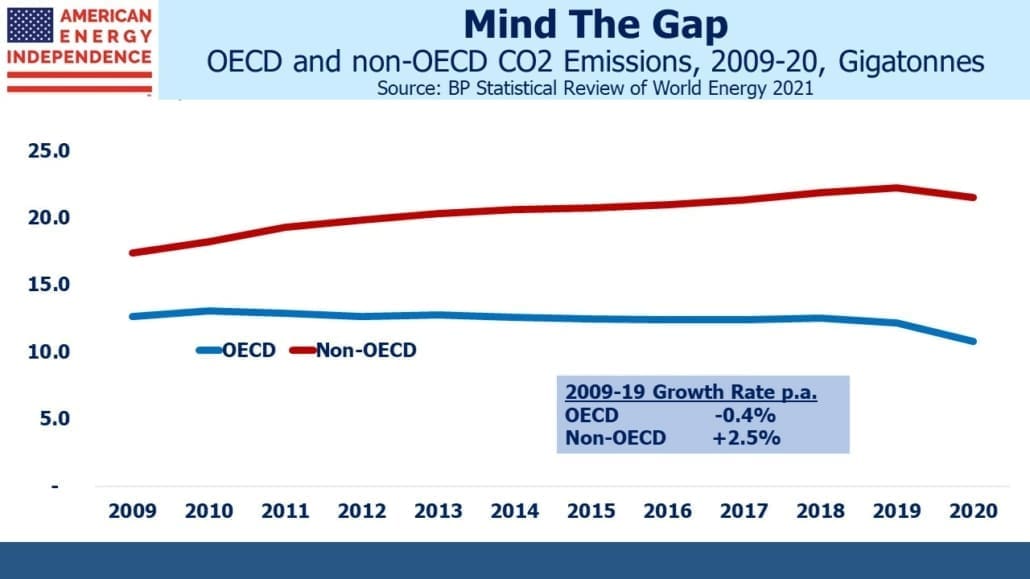

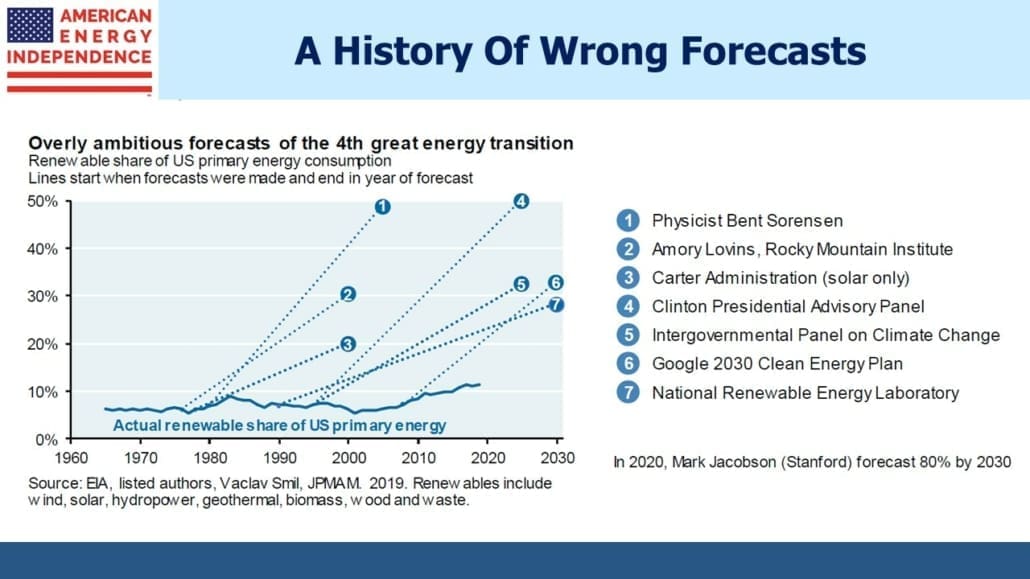

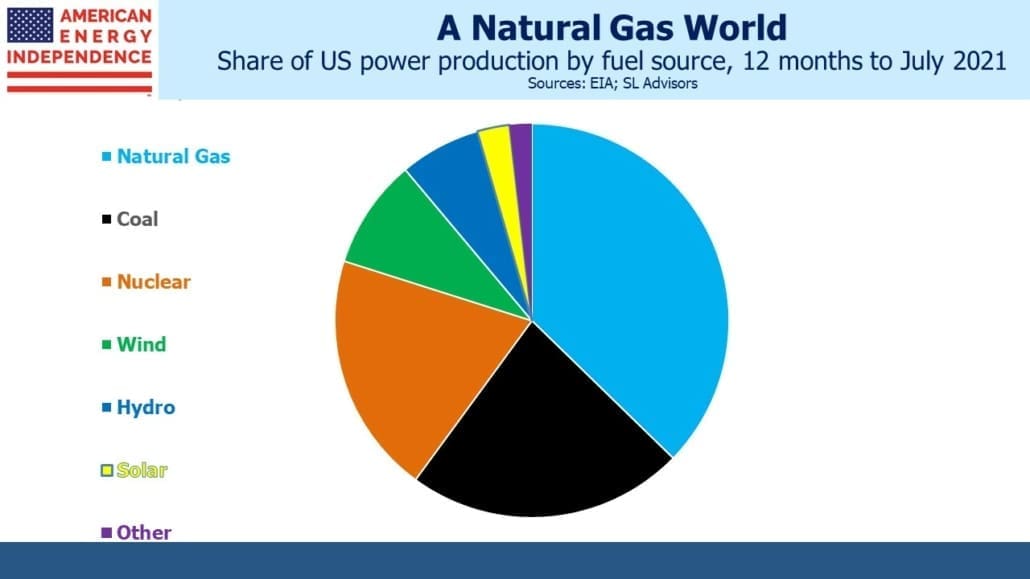

There’s little doubt that solar and wind will grow. But there aren’t many examples of intermittent power delivering the cheap energy and attractive jobs that progressives keep promising (listen to our podcast Incoherent Energy Policy). Failures are becoming more visible and costly – sky-high prices for Liquified Natural Gas (LNG) in Europe and Asia are the latest example of the recklessness of turning public policy against existing energy supplies while new ones remain inadequate.

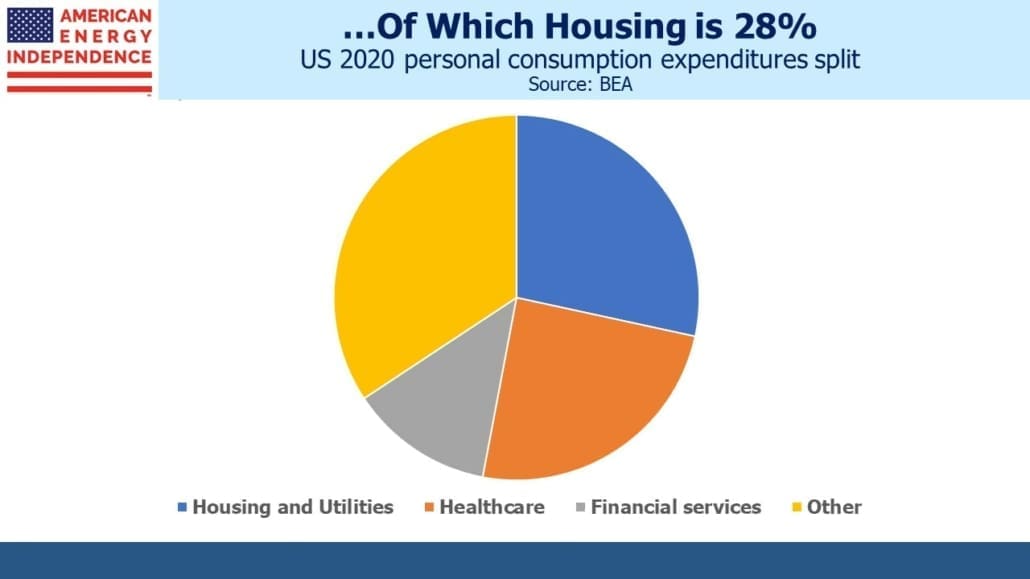

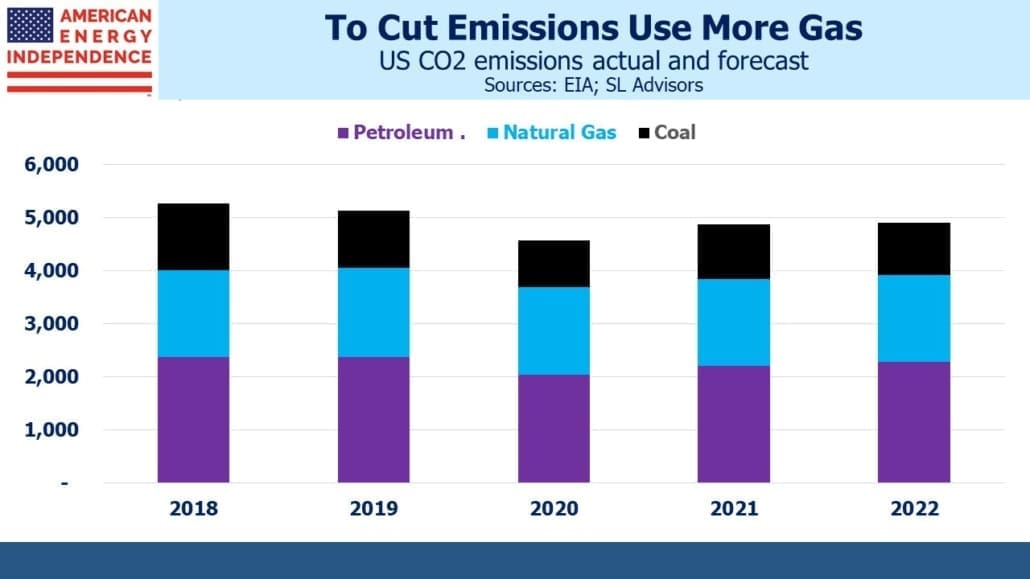

Practical solutions may gain traction, including acknowledging a slower energy transition, increased use of nuclear, favoring natural gas over coal and boosting incentives for hydrogen, and for carbon capture and storage from the use of existing, reliable energy. Looking at the figures instead of the media’s breathless coverage, renewables are insignificant yet disruptive.

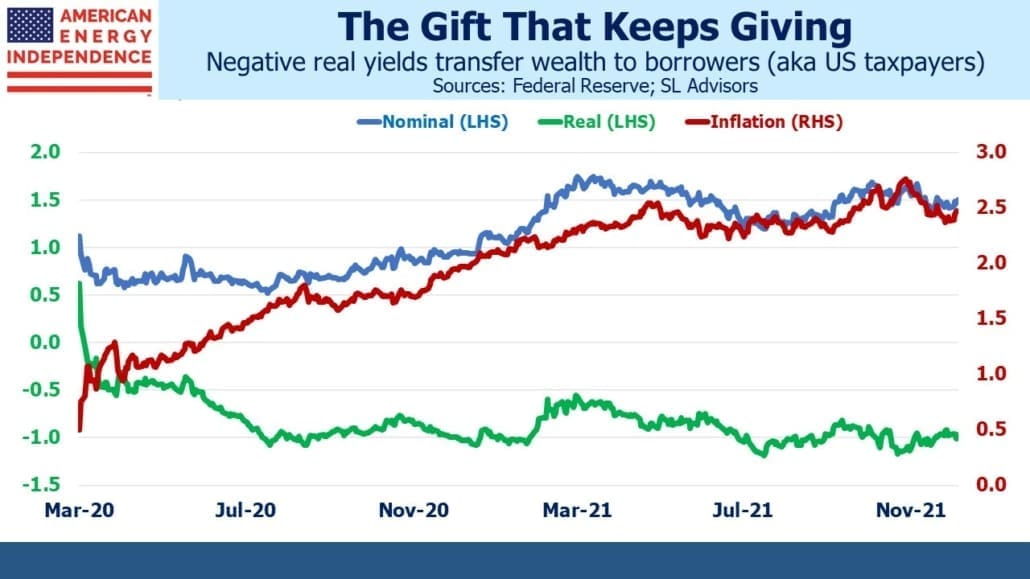

3) Real yields continue to fall

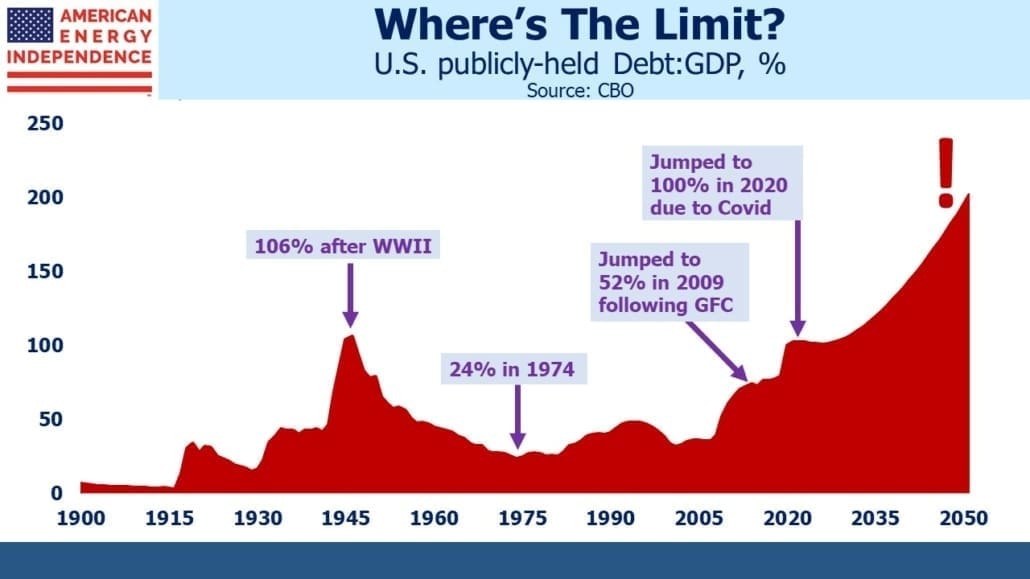

Ten year TIPs yields of –1.0% already seem impossibly low, but there is no theoretical limit to how far they can fall. This may temper an otherwise inevitable increase in bond yields, by projecting higher inflation expectations without a rise in nominal yields. The fall in real yields traces back decades and there’s no reason to think it stops here. It represents an enormous wealth transfer from those who must own sovereign debt — foreign central banks, pension funds and others with inflexible investment mandates. The beneficiaries are borrowers, chiefly the US government and by extension, taxpayers. It’s why our dire fiscal outlook continues – there is little discernible cost.

If these current trends continue the appeal of stable income with inflation protection, which real assets (including pipelines) offer, could become irresistible. Fixed income remains a completely losing proposition.

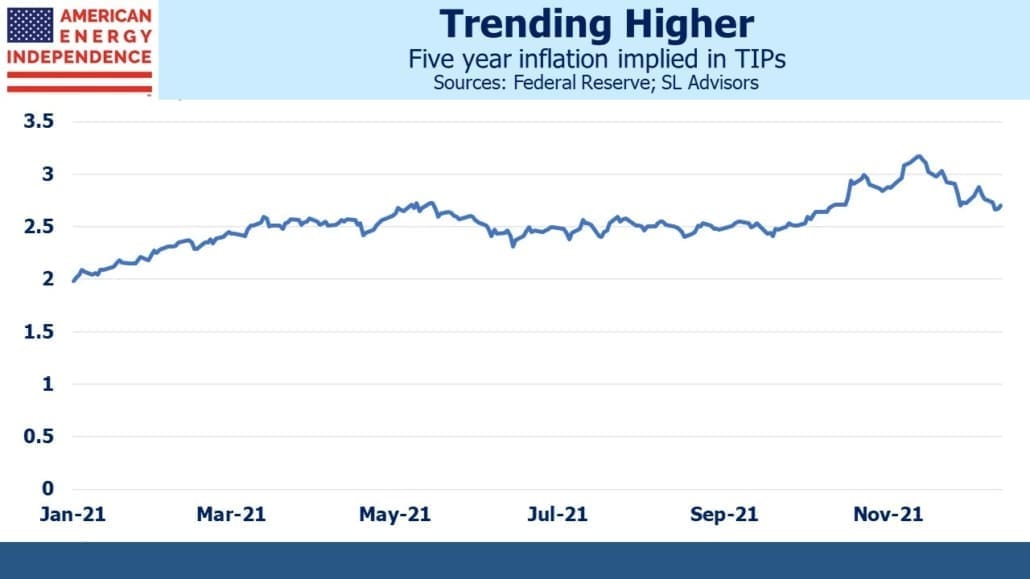

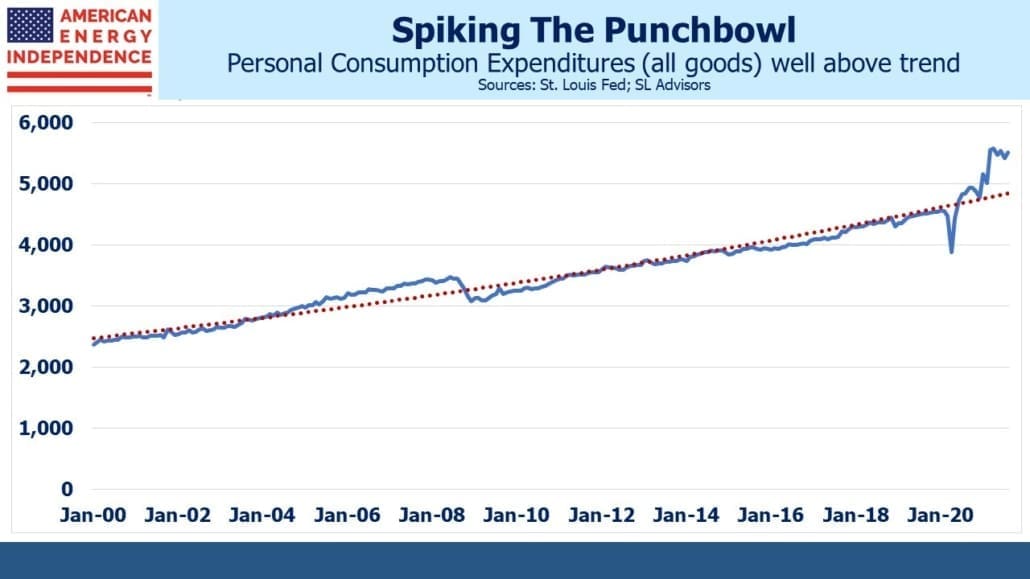

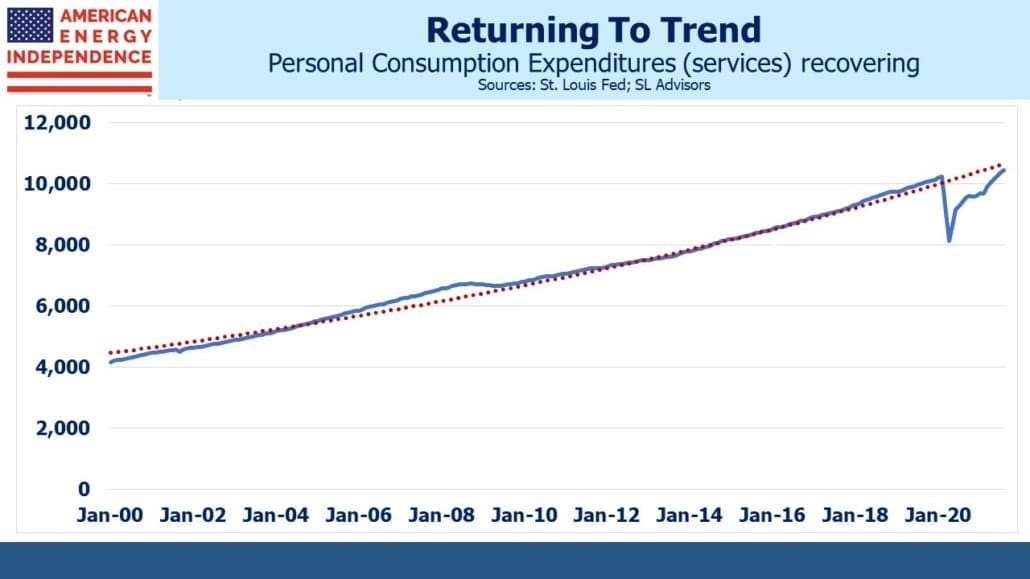

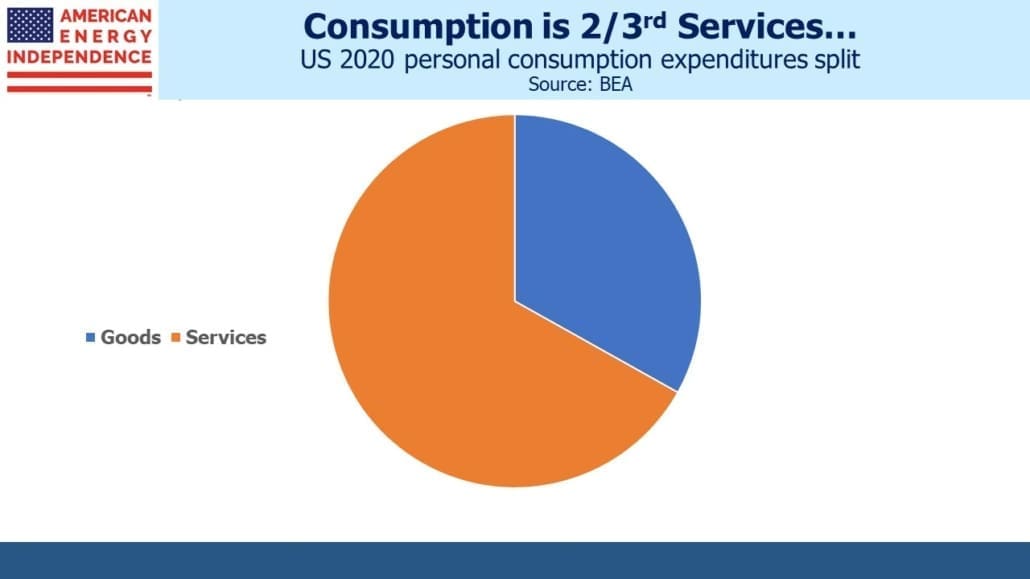

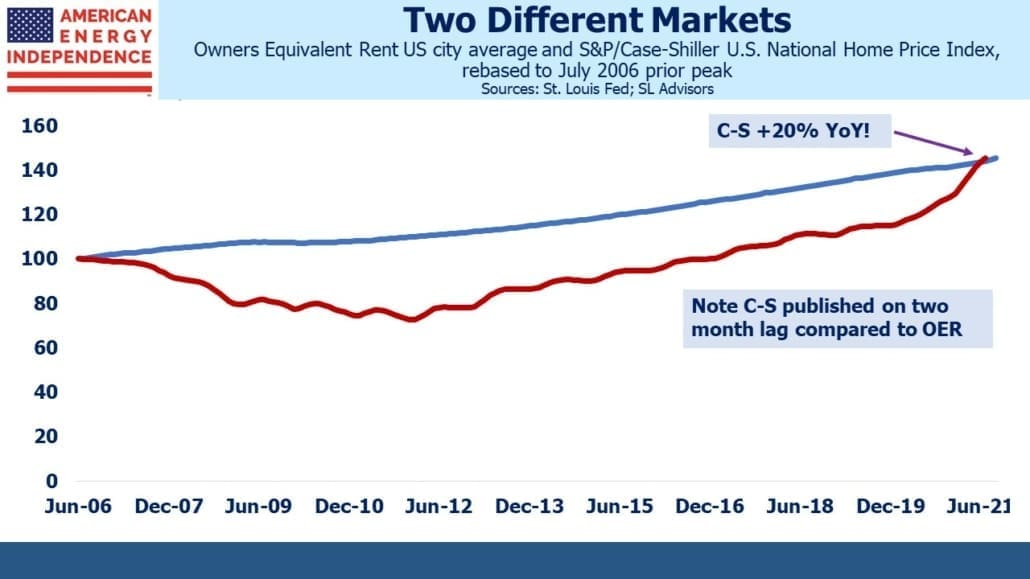

4) Inflation surprises to the upside

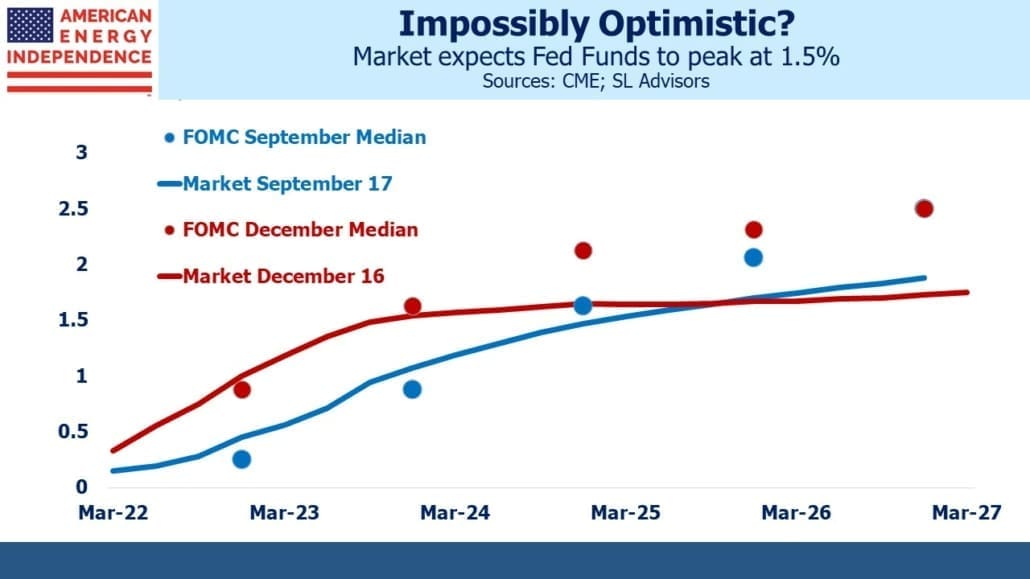

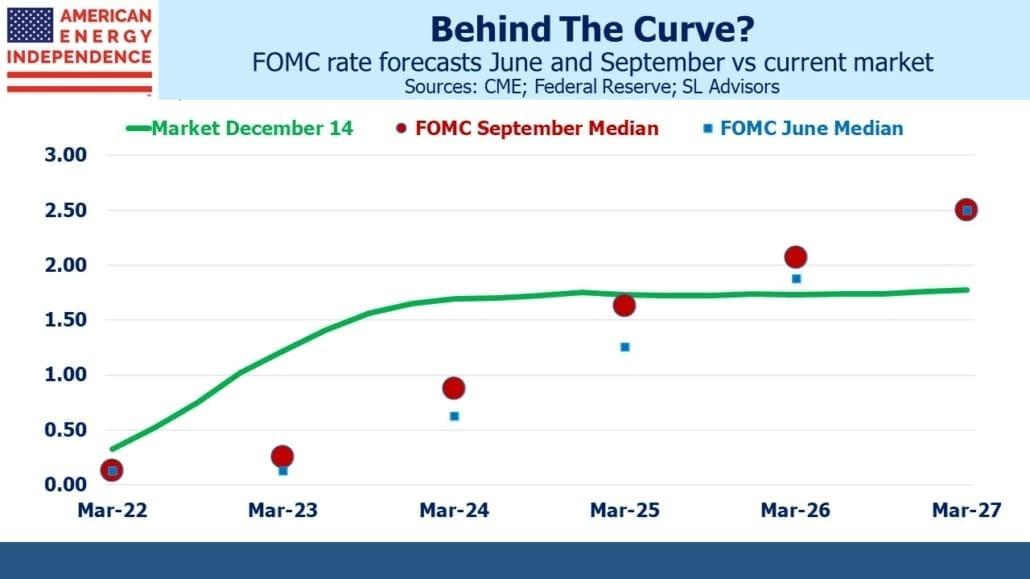

Most forecasters expect inflation to fall substantially in 2022. However, there are plenty of indications that Americans expect it to remain elevated. Low bond yields mean the yield curve could invert with as little as 1.5% of tightening by the Fed. This traditional precursor of a recession is likely to create offsetting concern about employment.

Having helped cause inflation, the Fed’s tools will as usual be blunt and they’ll face the unenviable choice between throwing people out of work or tolerating inflation closer to 3%. The return to 2% inflation over the long run is by no means assured. Real assets such as pipelines would benefit.

5) Republican mid-term gains squash any anti-energy sector legislation

Build Back Better remains alive and could pass in a further reduced form with climate change policies. Whether Joe Manchin and the White House reach agreement or not, this is probably the progressives’ last opportunity to implement the less extreme elements of their wish list.

A shift of the House back to Republican control, or the loss of one Democrat senator would leave executive actions as the only remaining tool. Perhaps this would even lead to a more substantive dialogue about the energy transition – one that acknowledges the cost and seeks to justify it, doesn’t falsely claim thousands of new jobs and explains why it’s in our interests to continue reducing emissions while most emerging economies are growing theirs. A thoughtful debate about how to manage the possible risks of increased emissions is overdue.

6) Sector fund flows turn positive

Sentiment is no longer negative and is showing signs of cautious optimism, at least based on the dozens of calls we’ve had in recent weeks. Fund flows turned negative in February 2020, and just turned positive two months ago. The sector has enjoyed a strong rally without significant retail participation. If the trend on inflows persists that could provide a significant boost.

Any one of these factors could push pipeline stocks higher. There remains plenty of opportunity for upside surprises.

We have three funds that seek to profit from this environment:

Energy Mutual Fund Energy ETF Real Assets FundPlease see important Legal Disclosures.