Will The Fed Catch Up With The Curve?

It’s easy to criticize the Fed. They’ve maintained their uber-accommodative monetary policy for probably a year longer than needed. Once the vaccine breakthrough was announced last November, prudence dictated that they anticipate an economic rebound and begin normalizing rates.

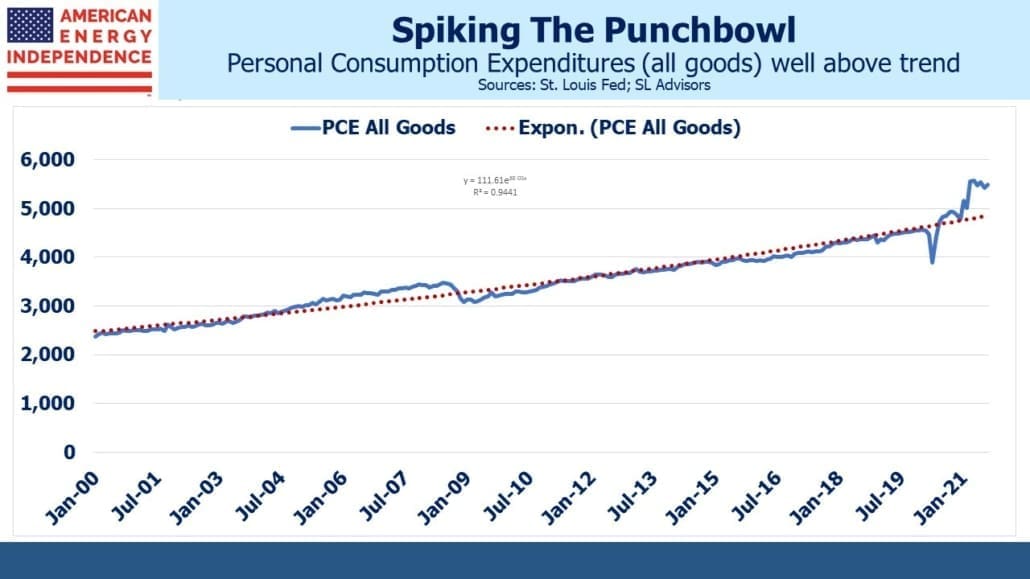

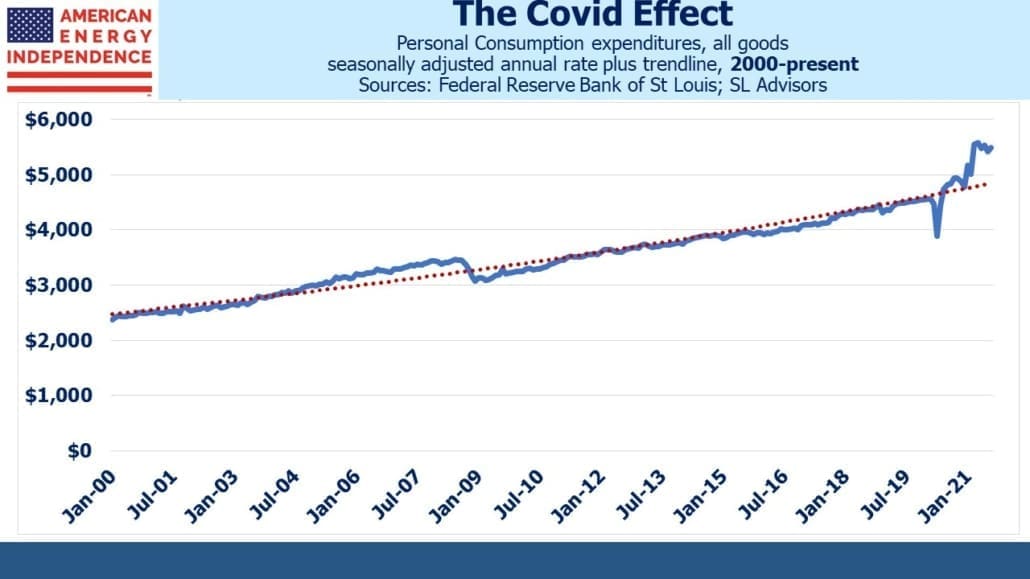

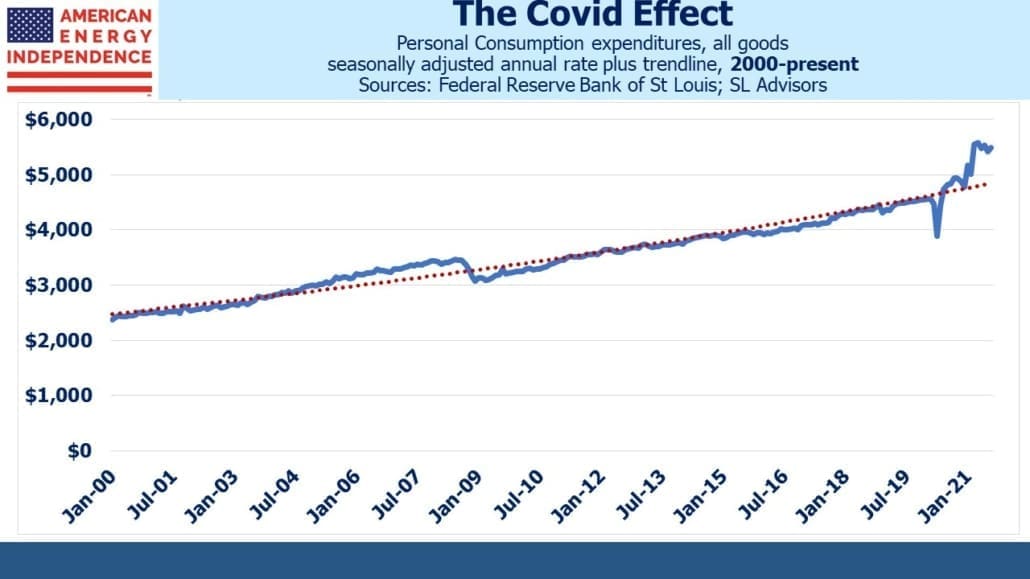

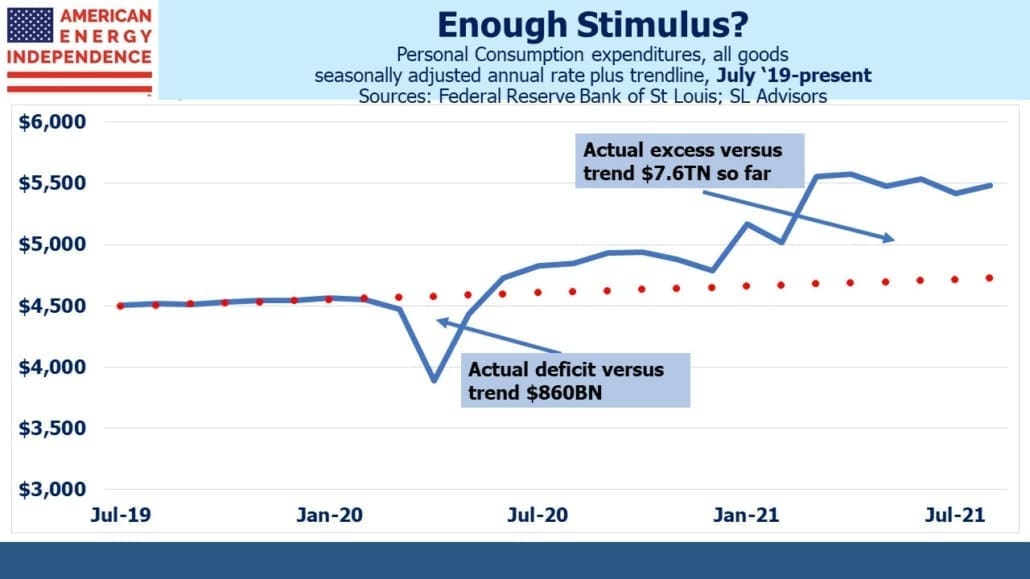

Instead their bond buying has had the effect of partially monetizing Federal debt issued to fund the huge fiscal response to the pandemic. The March stimulus package was clearly an additional $1.9TN in buying power that consumers collectively didn’t need, which is why personal consumption expenditures on goods are running well above the long term trend.

The relevant quote from former Fed chair William McChesney Martin, Jr., as lifted from his written speech is, “The Federal Reserve…is in the position of the chaperone who has ordered the punch bowl removed just when the party was really warming up.” Instead, current chair Jay Powell and his colleagues have been pouring in the Absolut.

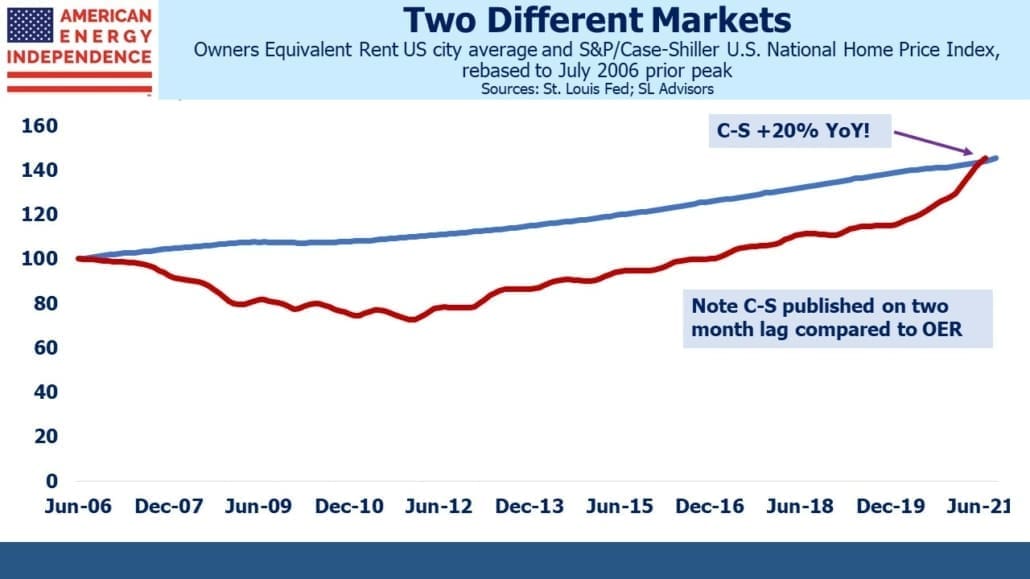

Housing is another example. The FOMC must be the only group of Americans unaware that suburban residential real estate is red hot, making it more expensive for the two thirds of American households who choose to own their home to find shelter. Owners’ Equivalent Rent (OER) allows them to pretend that nothing untoward is happening, in willful defiance of the S&P/Case-Shiller U.S. National Home Price Index (C-S).

By coincidence, since the last housing peak in July 2006 both indices have increased by approximately the same amount. The real estate market has felt a lot different to consumers versus the number crunchers at the Bureau of Labor Statistics who produce OER. They might even argue that this shows OER is a decent proxy for housing. However, the C-S is +20% over the past year.

The Fed is still buying $40BN of mortgage-backed securities every month. Even though they’re winding down, at their current tapering pace they won’t be completely out of the market until June.

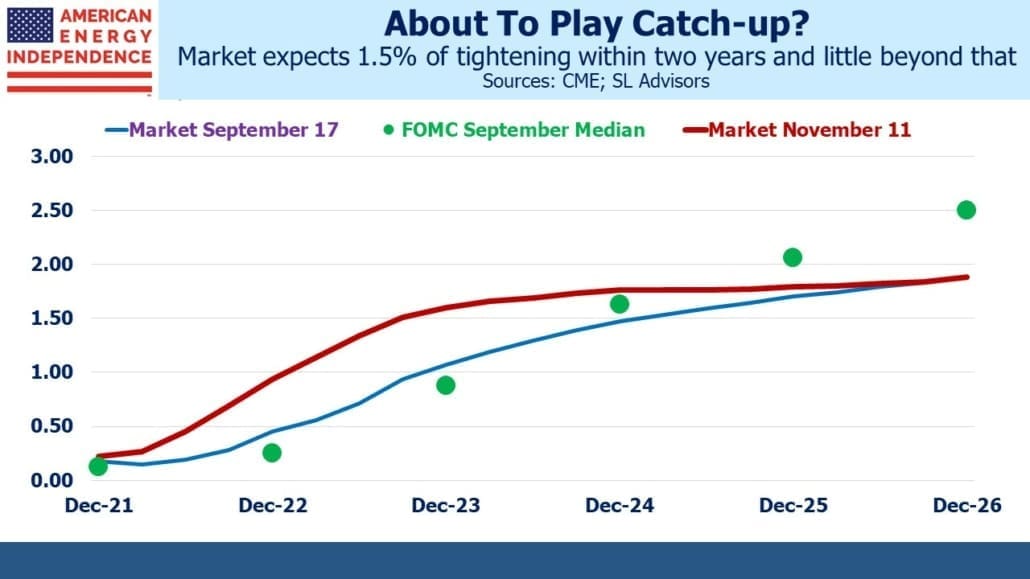

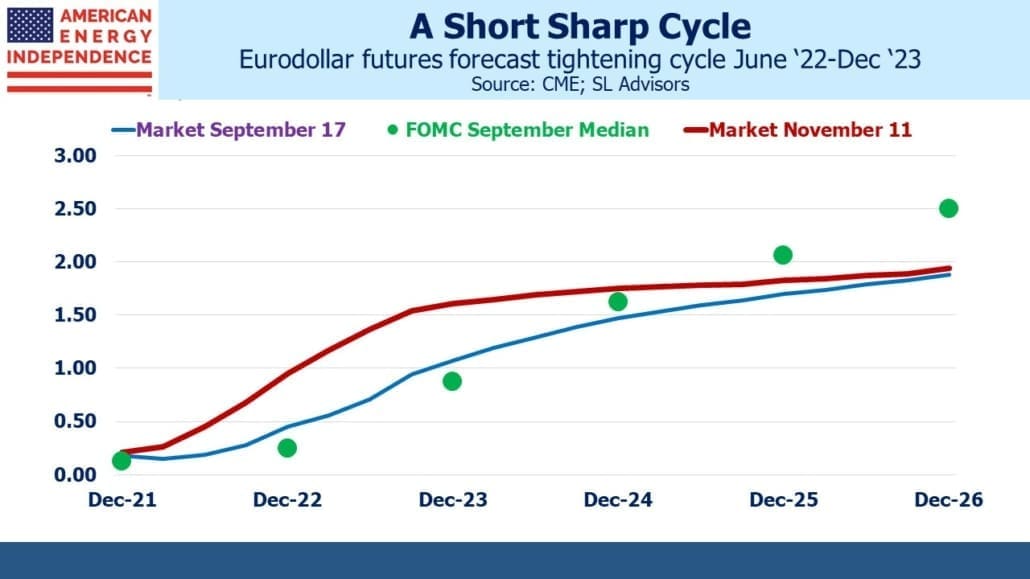

It’s easy to criticize the Fed. Markets have priced in a significantly more rapid tightening than the most recent FOMC projection materials, with almost no public comments from officials that such was likely. With inflation running at 6.2% it’s easy to see why.

So it’s interesting to consider the defense of the Fed, one that the Fed chair may offer once Biden has announced his choice.

Reports that the White House is considering replacing Powell with Lael Brainard are likely all optics, and although some commentators perceive Brainard as more dovish, the FOMC has maintained the monetary gusher without much public dissent. They’re all doves.

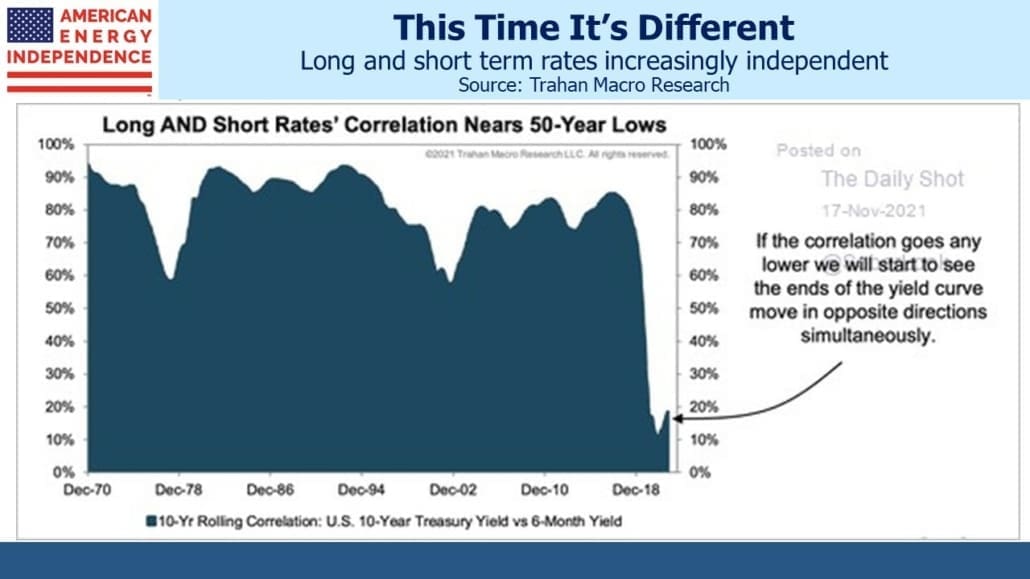

It starts with financial markets – one of the more interesting recent charts is the one showing an unprecedented drop in the correlation between short term and long term rates. The bond market used to be a real-time measure of Fed policy, but inflation expectations and monetary policy seem to play less of a role than in the past. This may be why the correlation has dropped.

Anchored by central bank buying and other return-oblivious investors, bonds seem impervious to rising consumer prices.

Ten year treasuries at 1.6% are hardly onerous unless you think you’re entitled to a return on your money, a requirement bond investors have abandoned. TIPs yield –1.1%, so the ten year inflation expectation is 2.7%. This is somewhat higher than the Fed’s 2% target but not out of control, and not inconsistent with the Fed’s optimistically transitive narrative.

The recent shift in tightening expectations has been almost exclusively reflected in the short end of the curve. The precise market forecasts offered by eurodollar futures show that traders expect any tightening to be completed within two years or less, with stability thereafter. Ten year treasuries yield the same 1.6% as they did in May.

The Fed’s $8.5TN balance sheet has helped depress bond yields, but now the buying will slowly stop and the market knows that. There’s no shortage of other return-insensitive buyers for debt of a profligate government, starting with Japan ($1.3TN) and China ($1TN).

Interest rates are the transmission mechanism by which lenders receive compensation for inflation. In a world of negative real yields, perhaps the economy can tolerate some inflation.

The buoyant stock market is another financial market indicator that current and expected inflation aren’t creating any big problems. Quarterly earnings show that many companies seem able to pass through higher costs to their customers.

There are numerous signs that the jobs market is strong, with September job openings of 10.4 million just below August’s record of 10.6 million. Workers are increasingly willing to quit for a better job, and companies routinely complain of difficulties hiring enough qualified workers.

Unusually, inflation has become a political problem before becoming a markets problem. More common, for those of us old enough to remember tightening cycles, is for bond yields to rise, compensating investors for the risk of higher inflation and pressuring stocks. The administration, usually subtly, pushes back.

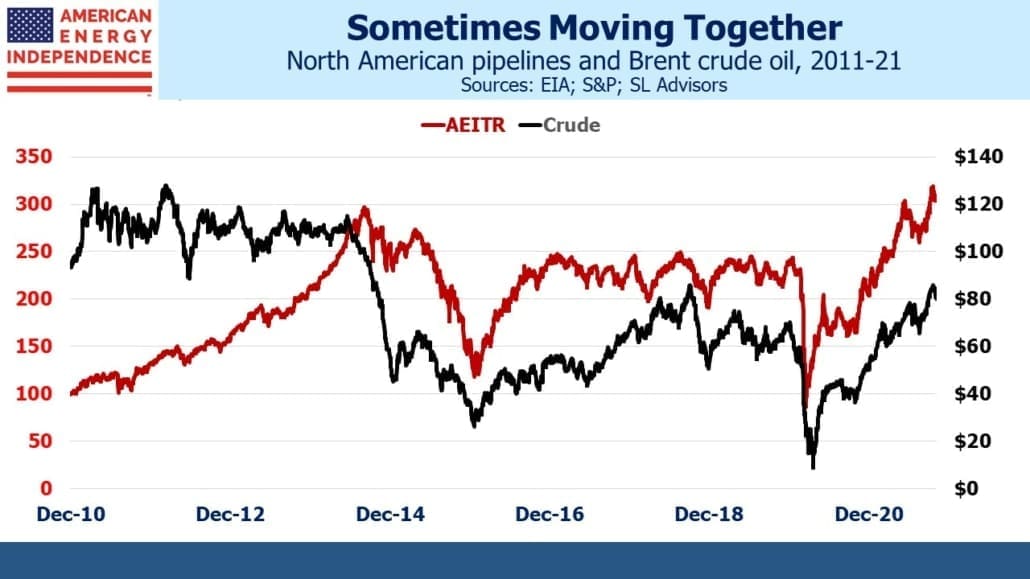

Today talk of inflation is everywhere, but anyone invested in stocks is still ahead of the game. For my part, stopping at a gas station has become a cause for unseemly celebration as I happily fork over an extra $40 while smiling at the bull market in pipeline stocks.

Borrowers are also benefiting from continued low rates.

The point is, today’s inflation is not an economic problem but a political one. Raising rates so as to drive up the unemployment rate won’t produce more truck drivers and will only appease the talking heads who are the visible pressure for action. An FOMC that has willingly monetized debt, synchronized easy policy with enormous fiscal stimulus and promoted a housing bubble doesn’t look like a group to willingly cause economic damage by hiking rates precipitously.

The FOMC will likely move slowly, because there’s plenty of justification for doing so. However, vice-chair Richard Clarida suggested on Friday a speedier tapering, which would allow faster tightening in line with current market prices. We think the FOMC’s dovish tendencies will incline them to move slowly – the market is priced for a more aggressive response.

We have three funds that seek to profit from this environment:

Energy Mutual Fund Energy ETF Real Assets FundPlease see important Legal Disclosures.