Buffett Finds Value in Shale

Warren Buffett likes the Permian Basin. This was clear from Berkshire’s (BRK) proposed $10BN preferred investment in Occidental (OXY) should they buy Anadarko (APC). Berkshire’s annual shareholder meeting was followed as usual with a Becky Quick interview on CNBC.

The 8% dividend on the preferred OXY will issue to finance their acquisition could be inducement enough for BRK to commit $10BN. When Becky commented on this Buffett responded “It isn’t great to have an 8% preferred if there isn’t any oil there. It’s a bet on oil prices over the long term more than anything else and it’s also a bet on the fact that the Permian basin is what’s it’s cracked up to be. … You have to have a view on oil over time and Charlie and I have got some views on that.”

This led Becky to ask why BRK didn’t use some of its cash hoard to buy Anardarko for $35BN, to which Buffett replied “Well, that might have happened if Anadarko had come to us.” Buffett was quick to clarify that he wouldn’t jump in to a bidding war with someone who has come to them for financing. Buffett wants more supplicants for similar deals. But it does show that they see value in the Permian Basin, OXY and APC.

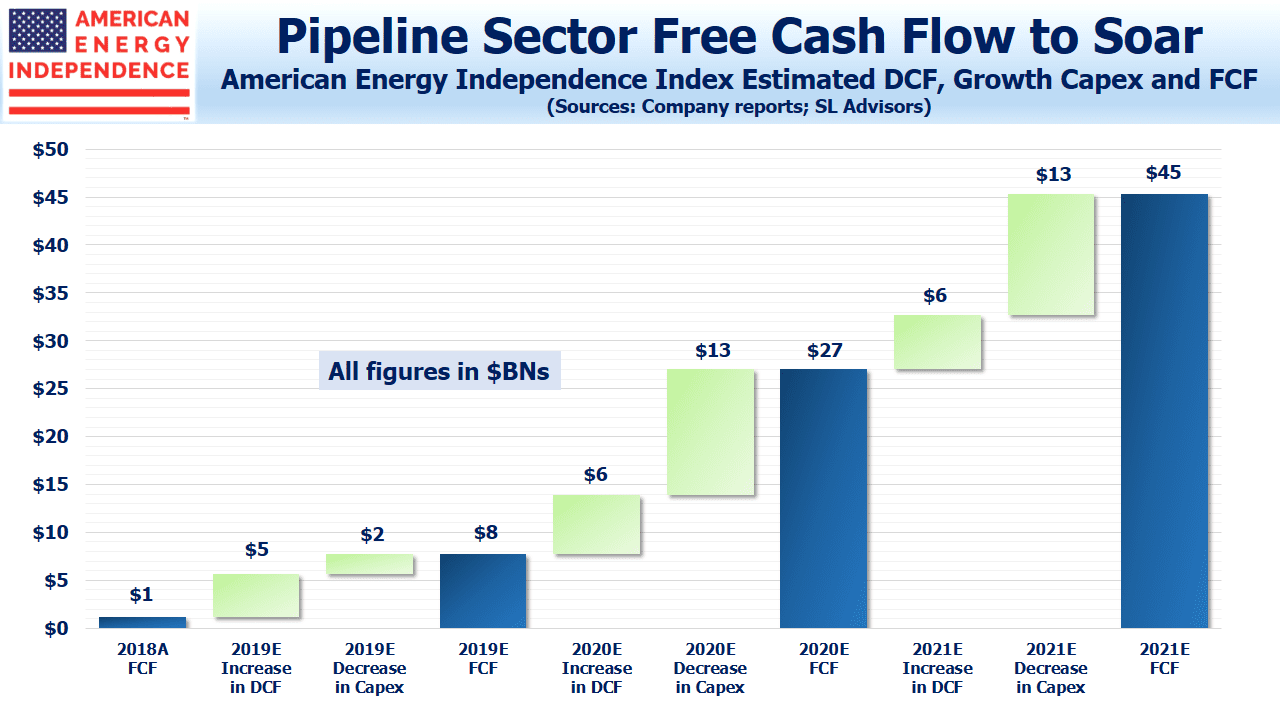

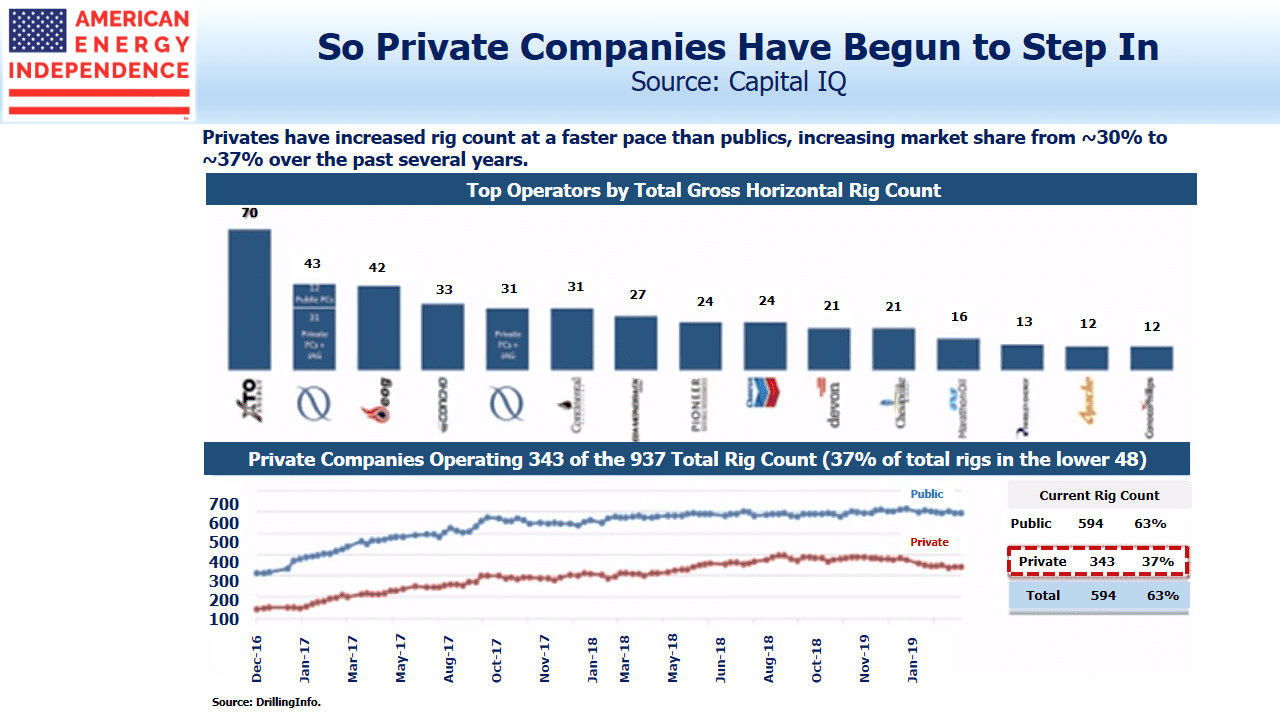

The competition between Chevron (CVX) and OXY to buy APC provides further confirmation of a bullish production outlook among those with the best information. CVX and OXY were the two biggest producers in the Permian last year, each pumping over 300 thousand barrels per day (MB/D). APC did 100 MB/D. They know the region. Rystad Energy believes that a CVX/APC combination would reach almost 1.4 Million Barrels per Day (MMB/D) in output by 2025. A match-up of OXY/APC would get to 0.9 MMB/D. Permian volumes are growing fast, and the influx of additional capital makes this even more likely. Midstream energy infrastructure is a sure winner.

As always, Buffett had some wonderful folksy quips. In discussing his 60-year partnership with Charlie Munger, he noted that they’d often disagreed but never had an argument. Munger sometimes concludes such debates with, “You’ll agree with me soon, because you’re smart and I’m right.”

Try using that at home with your significant other. Let us know how it goes – we’ll publish any credible stories.

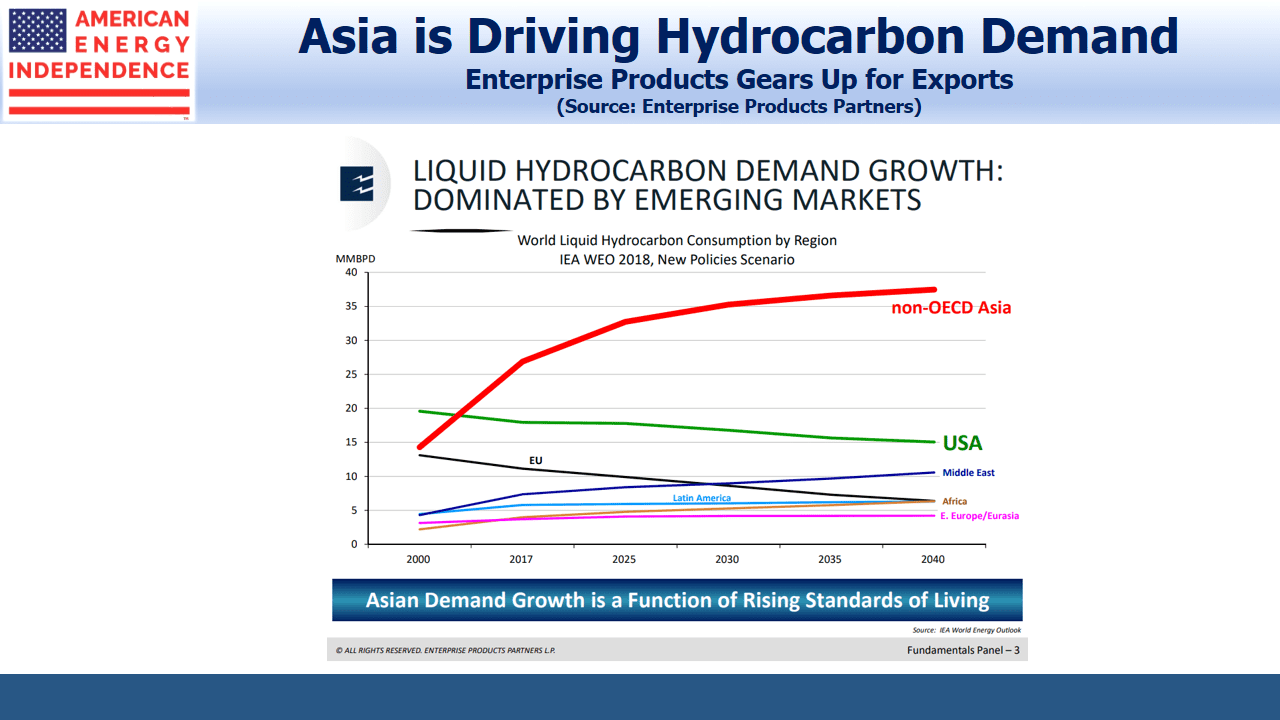

Buffett and Munger aren’t overly concerned about the latest ratcheting up of trade tensions. They believe both sides will benefit from concluding a deal. We agree that trade tensions are unlikely to be a factor entering 2020 when Trump is running for re-election (see The Trump Put). One easy way to reduce the trade deficit is for China to increase it’s purchases of raw materials from the U.S. This could include huge amounts of LNG, natural gas liquids such as propane, and light crude oil that they desperately want and need.

If the dispute is drawn out, planned Chinese purchases of U.S. Liquified Natural Gas (LNG) are at risk. But LNG is fungible, and U.S. exports could displace trade to other Asian countries whose shipments would in turn head to China. Cheniere Energy (ticker: LNG) and Chinese energy firm Sinopec are planning a 20 year LNG deal once the trade negotiations are concluded.

While a full-blown trade war that severely damages global GDP growth can have a meaningful impact on oil demand and oil prices, a resolution should boost demand and clear the way for Chinese buyers to sign long-term contracts from U.S oil and gas exporters.

Moreover, the U.S. just dispatched aircraft carrier Abraham Lincoln to the Persian Gulf so as to, “send a clear and unmistakable message to the Iranian regime…” The Shale Revolution has improved America’s ability to press our interests since we are so much less dependent on Middle East oil. Trump is not one to shy away from a fight. We won’t forecast how events with Iran will play out – but domestic energy investments are one of the safer places to be if there is conflict with Iran.

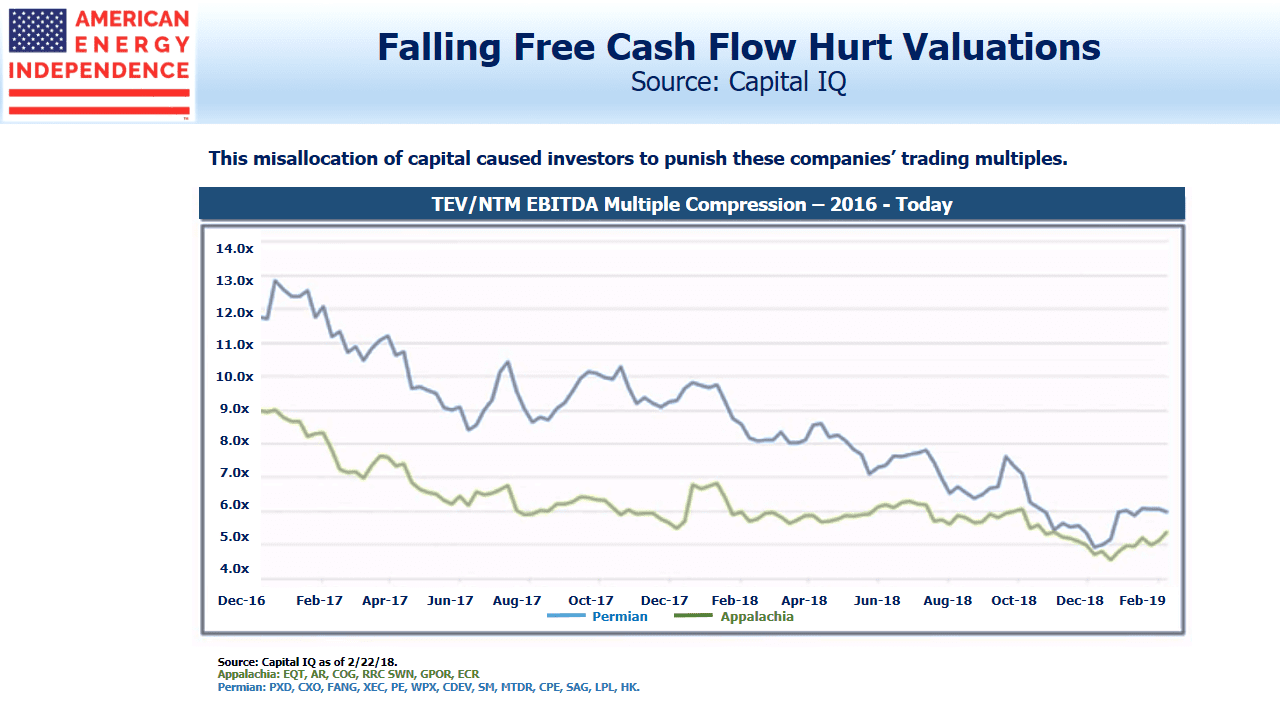

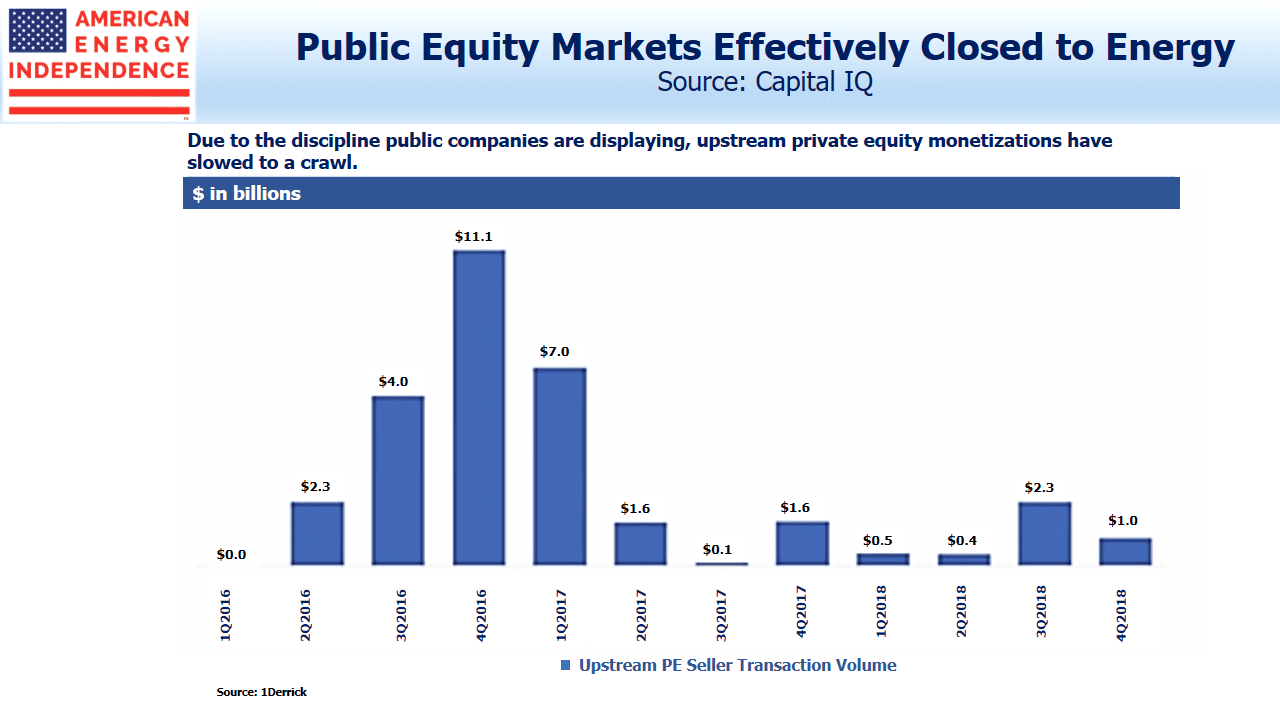

With historically low valuations for the energy sector, record oil & gas production, and solid growth prospects, the weekend’s news is showing energy to be one of the most overlooked areas in the market.

We are long BRK.

SL Advisors is the sub-advisor to the Catalyst MLP & Infrastructure Fund. To learn more about the Fund, please click here.

SL Advisors is also the advisor to an ETF (USAIETF.com).