Pipelines’ New Look

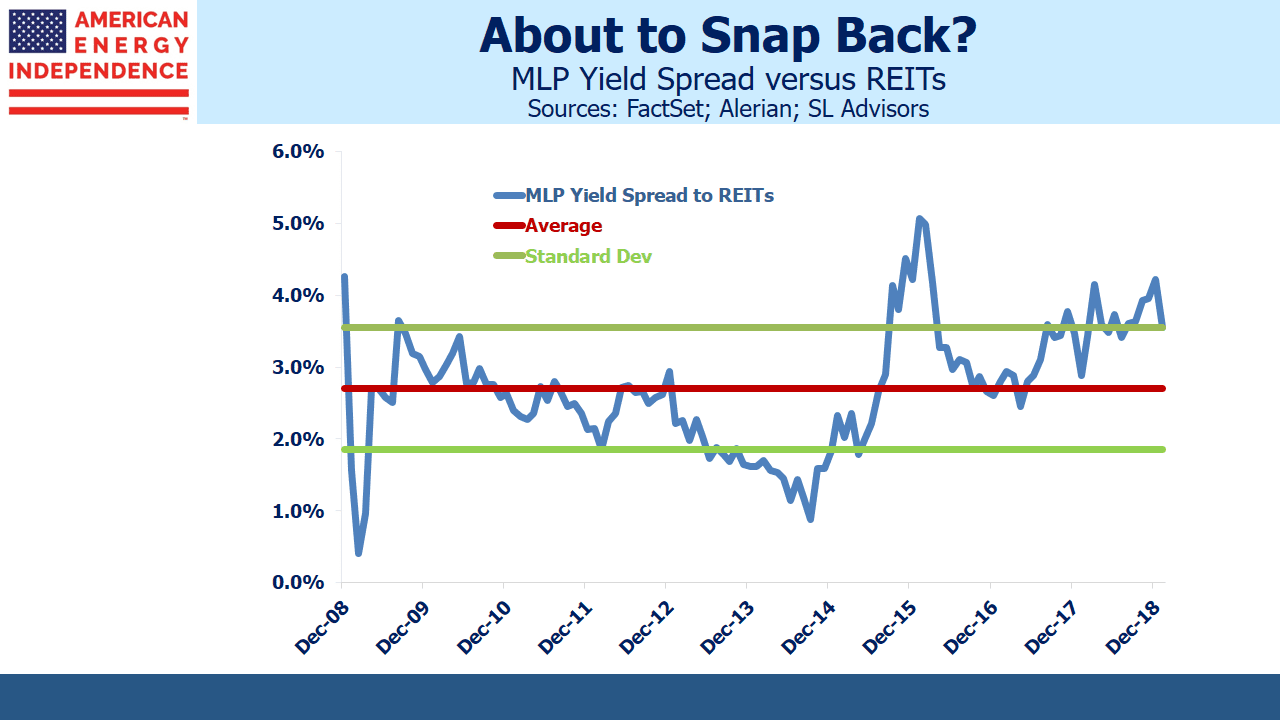

The point of a public equity listing is to be able to access public markets for financing, to use the stock as a currency for acquisitions, and to provide liquidity for investors. A company’s cost of equity moves inversely with its stock price, just like bond yields and prices. Access to cheap equity is vital for companies that have growth projects, including most energy infrastructure companies. MLPs continue to face a comparatively high cost of equity.

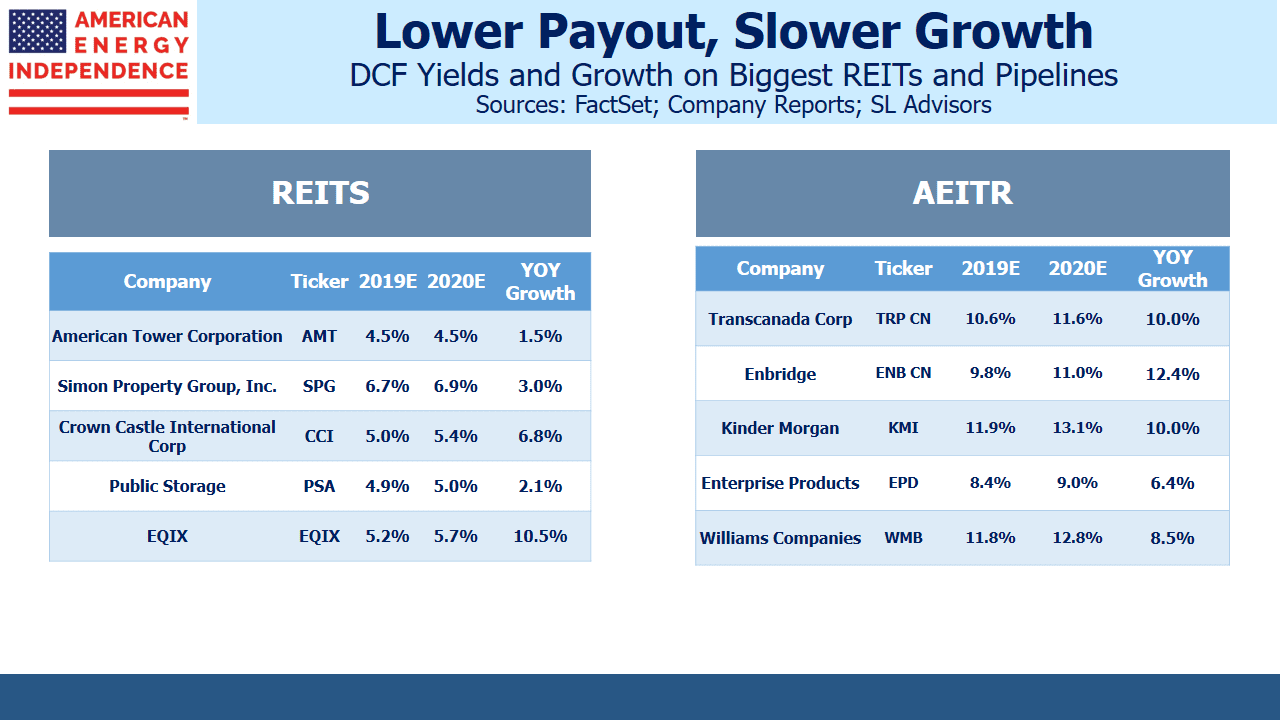

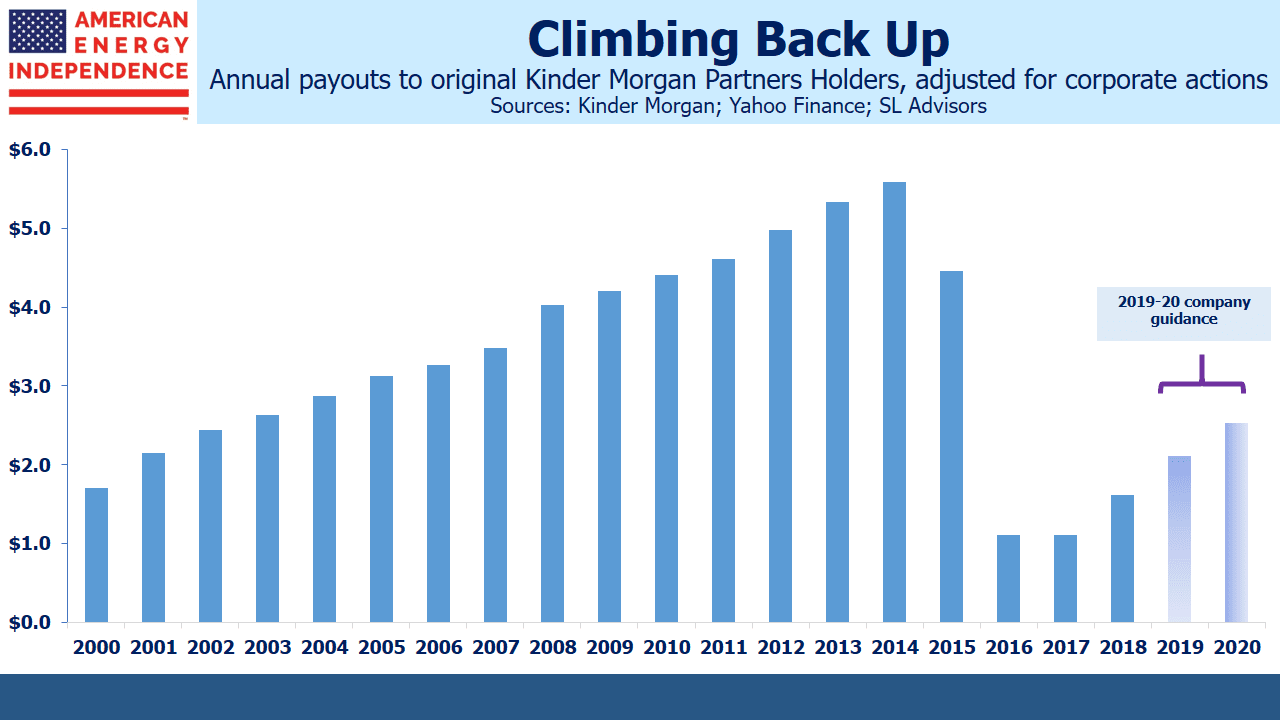

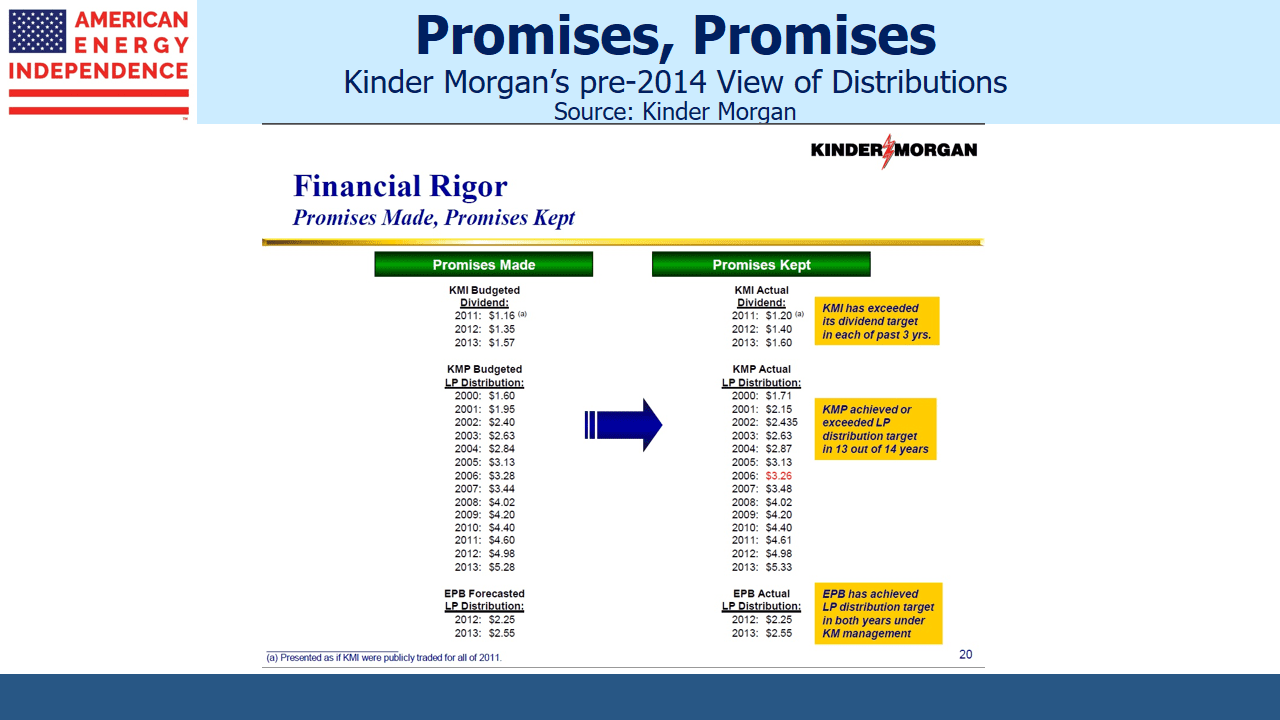

It’s one of the reasons why we believe over the past few years many of the biggest MLPs have “simplified”, which has often meant they’ve abandoned the MLP structure to become a regular corporation (a “c-corp”). An important objective behind each of these restructurings has been to lower their cost of equity. Kinder Morgan (KMI) led this move in 2014, when their desire for external capital to fund their backlog of growth projects collided with the interests of their income-seeking holders. Investors in Kinder Morgan Partners (KMP) weren’t much interested in plowing their distributions back into secondary offerings, so KMP’s yield rose to levels that made equity issuance uneconomic (see 2018 Lessons From The Pipeline Sector).

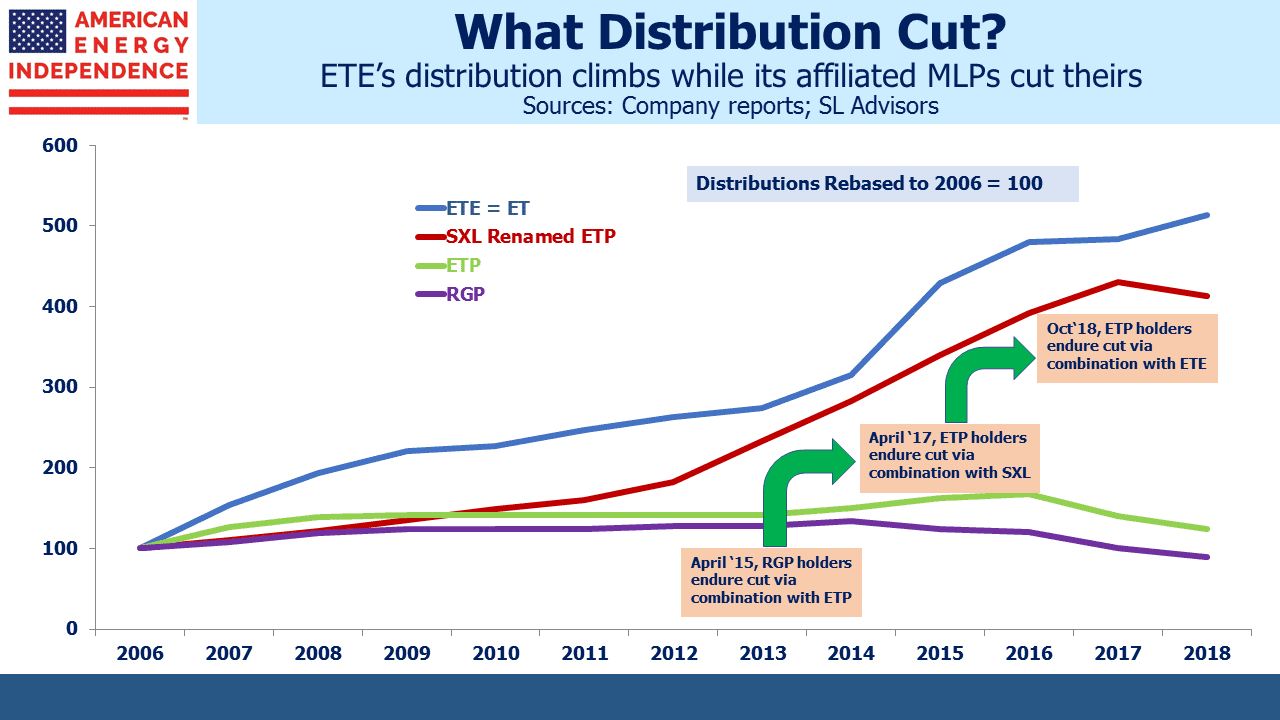

KMI decided to combine with KMP, creating unexpected tax bills for holders and leading (eventually) to two distribution cuts. The goal was to access a broader set of investors. Fewer than 10% of the money allocated to U.S. equities can invest in MLPs. Taxes and K-1s generally limit buyers to U.S. high net worth individuals. KMI wanted to reach U.S. pension funds, global sovereign wealth funds, and other significant buyers. They had outgrown the old, rich Americans, who used to own their stock. If you ever talk to a former KMP investor, you’ll learn how much bitterness this caused (see Kinder Morgan: Still Paying for Broken Promises).

Other MLPs followed, and today midstream energy infrastructure is more corporations than MLPs. The list includes Enbridge (ENB), Oneok (OKE), Pembina (PBA), Targa Resources (TRGP), Semgroup (SEMG), Transcanada (TRP) and Williams (WMB). None of these are in an MLP index.

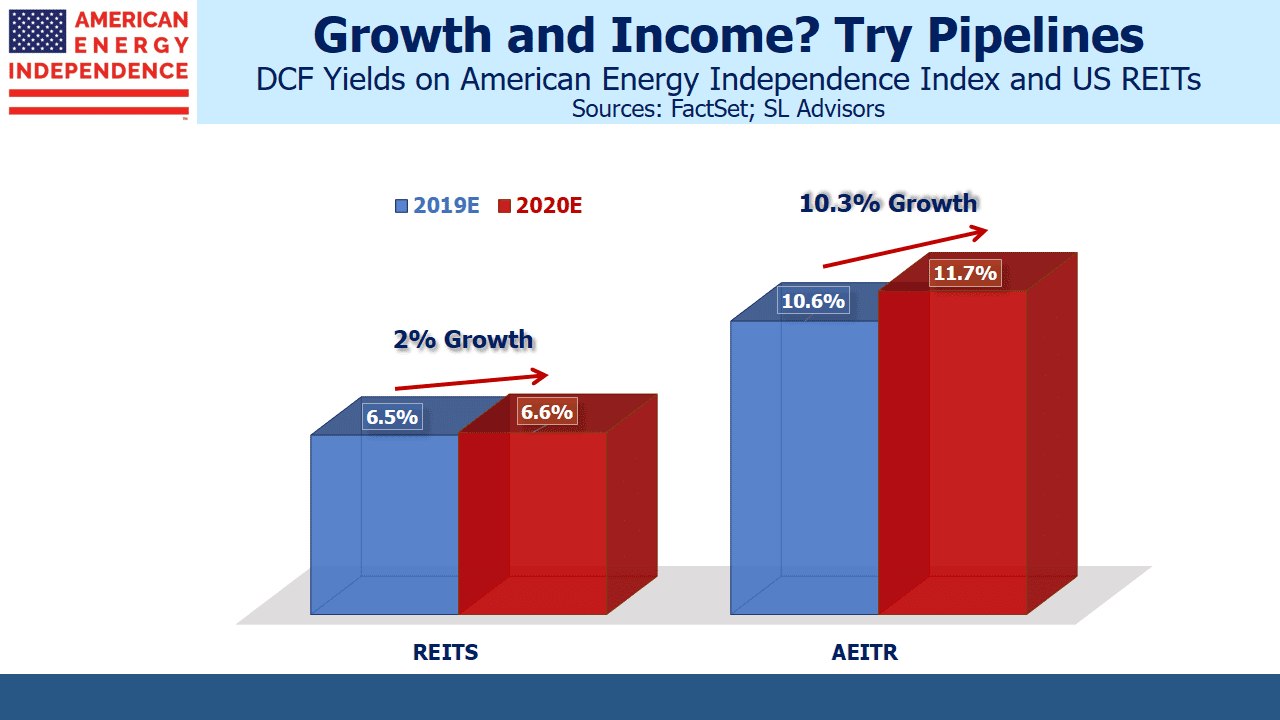

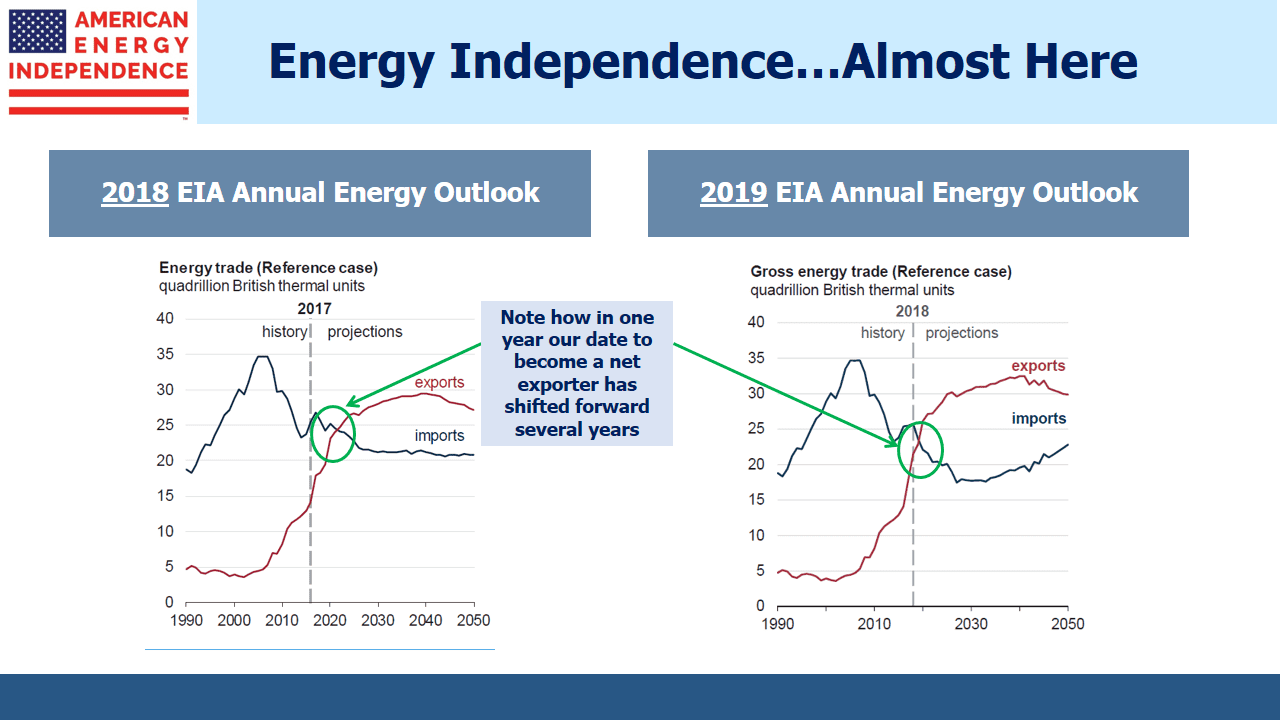

In late 2017 we created the investable American Energy Independence Index (AEITR). It’s a market-cap weighted index of North American energy infrastructure companies. It includes some MLPs, because the structure still works for those not in need of external equity. But MLPs are kept at 20%, reflecting their diminished role.

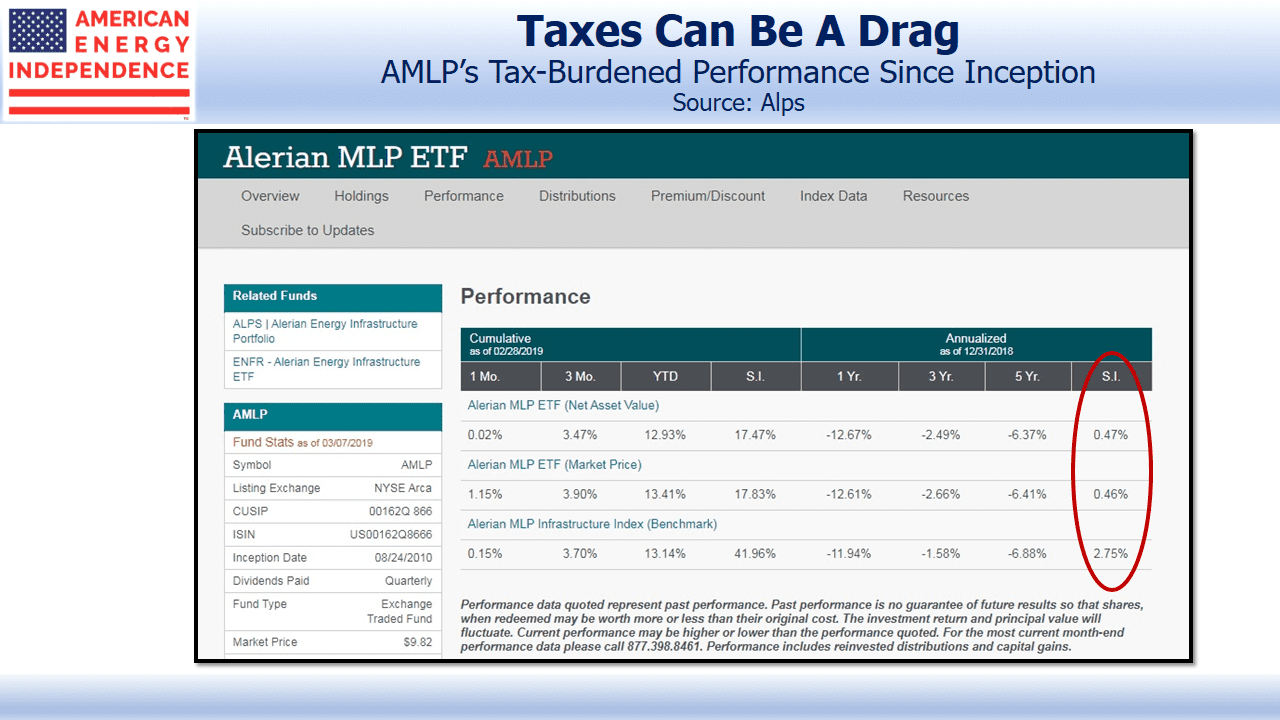

The AEITR’s limit on MLPs also means that funds linked to it aren’t subject to corporate tax. A flawed tax structure has been a substantial drag on performance for MLP-dedicated funds. For example, the Alerian MLP ETF (AMLP) has a since inception return of 0.47% p.a., compared with its index of 2.75%. It’s delivered less than a fifth of its index since 2010, in part because of a structure that requires it to pay corporate tax. Nobody would create such a fund today.

See MLP Funds Made for Uncle Sam for more detail.

The Alerian MLP indices are becoming outdated, because they represent what the pipeline business used to be, before MLPs started converting to corporations. An MLP-only approach to energy infrastructure misses most of the sector. MLPs aren’t going away, they’re just becoming less important.

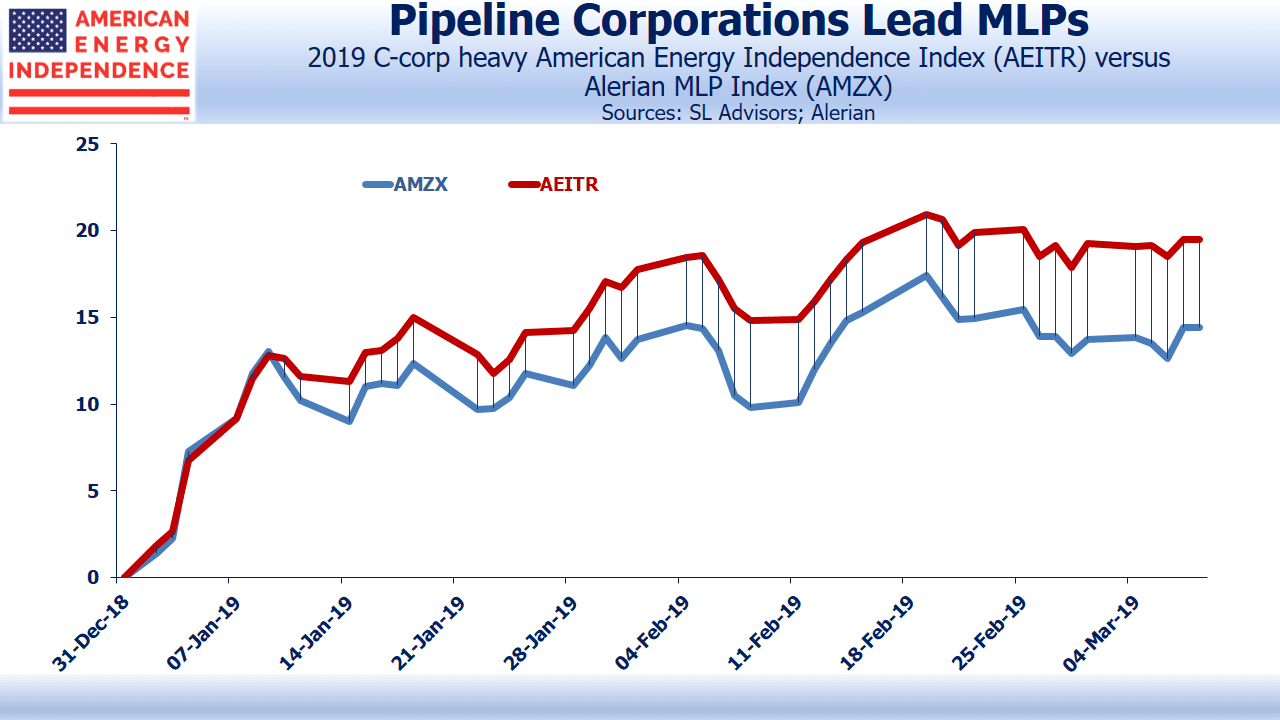

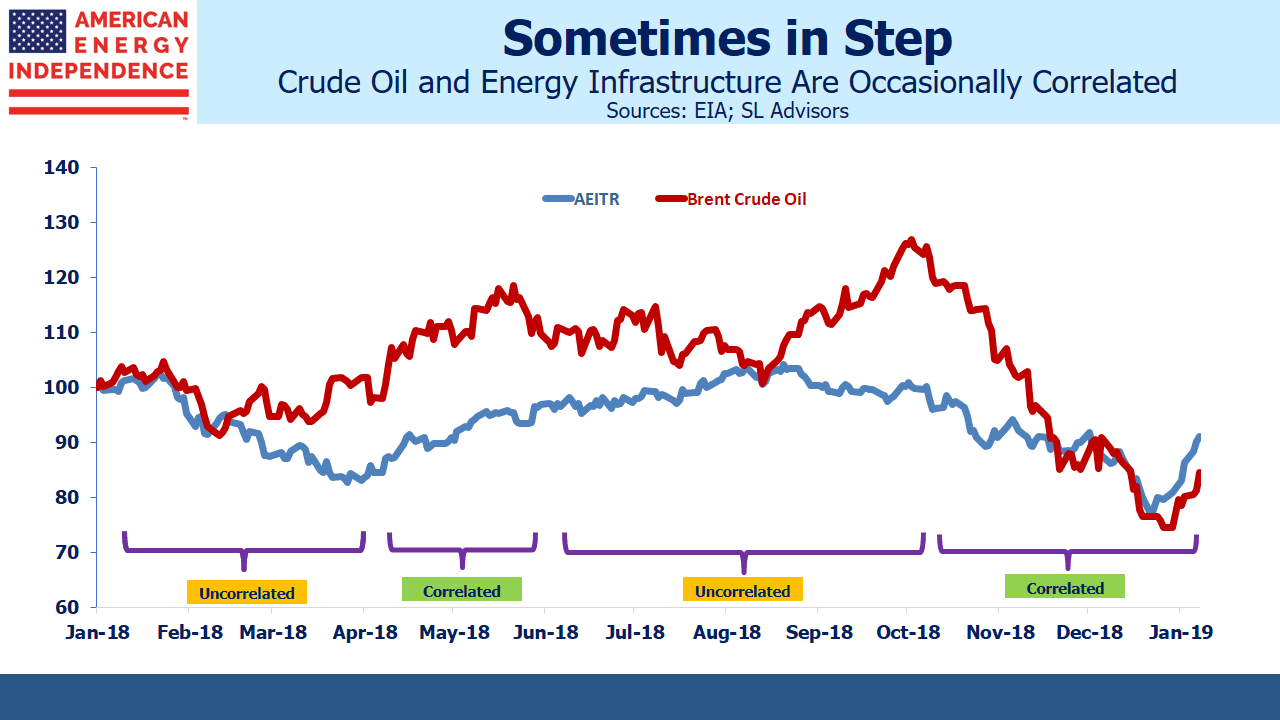

For the former MLPs who converted so as to lower their cost of capital, stock performance shows that these were good decisions. The AEITR’s 80% allocation to corporations makes it more representative than the Alerian MLP Index (AMZX). Performance differences between the two are driven by how corporations are doing relative to MLPs. This year, AEITR is 5% ahead.

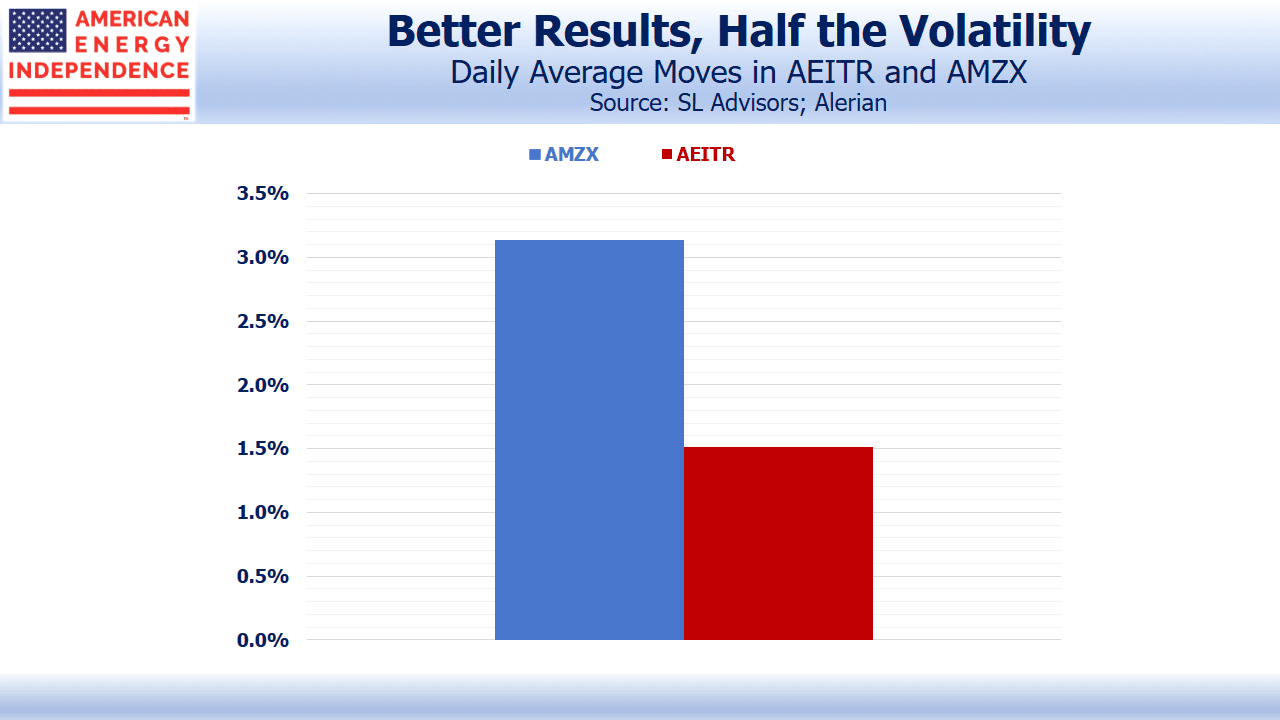

What’s also encouraging is that it’s coming with lower volatility. Since AEITR’s creation in October 2017, it has had average daily moves of 1.5%, half that of AMZX. This makes sense, because the corporations that make up 80% of AEITR have a wider pool of investors. It’s precisely why MLPs have been converting. A more diverse set of buyers means a deeper market, which lowers the risk for investors and thereby lowers the cost of capital for those companies.

So far, we haven’t heard of a company that regrets its decision to drop the MLP structure in a simplification, and those that remain get questions on every earnings call about their possible plans to simplify. There are some well run, attractive MLPs, including Enterprise Products Partners (EPD), Magellan Midstream Partners (MMP), Energy Transfer LP (ET), Western Gas Partners (WES), and Crestwood Equity Partners (CEQP). But the evidence is mounting that the adoption of a corporate structure and the global investor base that comes with it is beneficial.

We are invested in ENB, EPD, ET, KMI, MMP, OKE, PBA, SEMG, TRGP, TRP, WMB.

We are short AMLP.

SL Advisors is the sub-advisor to the Catalyst MLP & Infrastructure Fund. To learn more about the Fund, please click here.

SL Advisors is also the advisor to an ETF (USAIETF.com)