Momentum Crash Supports Pipeline Sector

Breaking News — Drone attack disables Saudi crude ouput

Although we don’t normally highlight the favorable geopolitics of U.S. midstream energy infrastructure, this news does emphasize that much of the world’s crude oil comes from unstable regions. See WSJ story U.S. Insulated From Possible Supply Shock After Saudi Attack

Momentum Crash Supports Pipeline Sector

The action in equity markets last week was beneath the surface. Daily moves in the S&P500 were unremarkable, but a sharp turn in momentum stocks caused lots of churning.

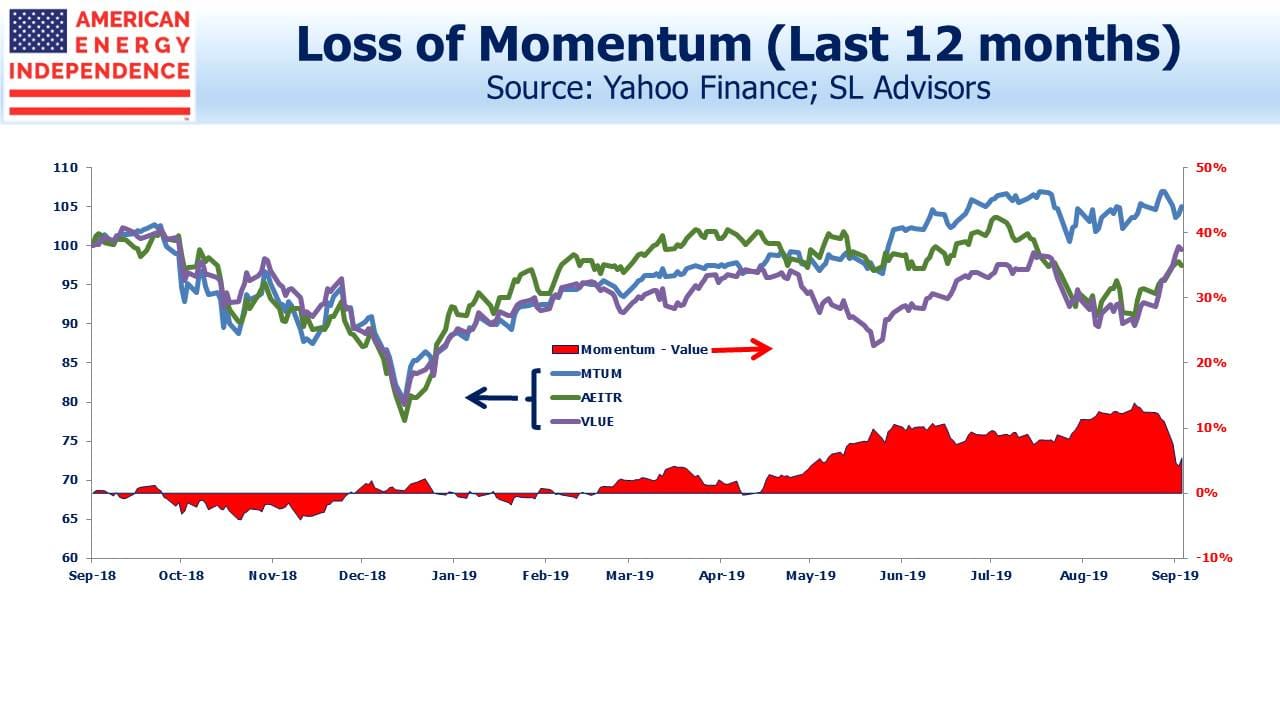

The resulting shift into value was welcome news for energy investors. Momentum and Value had tracked each other reasonably well for the past year until May, when Momentum began to outperform.

Eventually midstream energy infrastructure (defined as the American Energy Independence Index, AEITR), and Value both weakened during the summer. By late August, Momentum had opened up a 14% gap against Value over the prior five months, with similar outperformance against AEITR.

As portfolio managers in the pipeline sector we often struggle to explain the moves in the stocks we own. Apart from earnings season, macroeconomic developments and fund flows dominate. This past period was especially hard to understand because 2Q19 earnings reports were generally as expected.

In September this trend has reversed (see Drop in hot stocks stirs memories of ‘quant quake’), for reasons no clearer than those that preceded it. Value is 8% ahead of Momentum since Labor Day, lifting the AEITR with it.

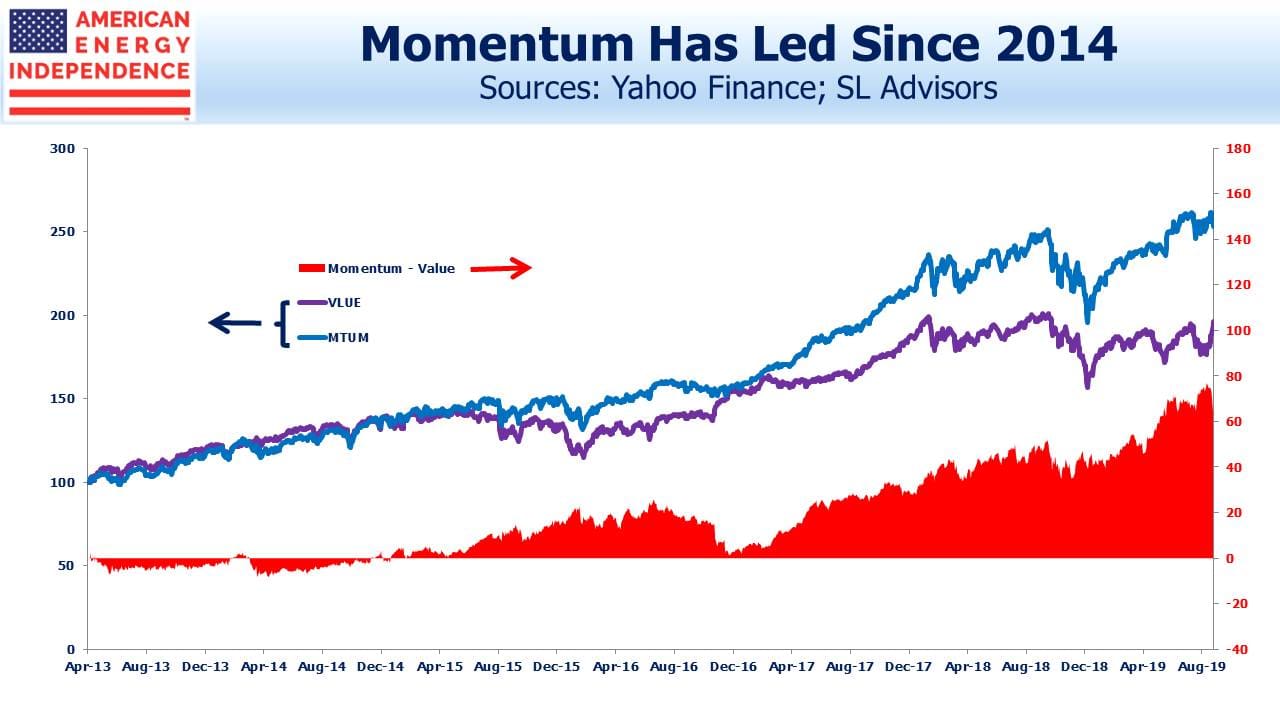

What’s behind this? Large pools of capital are deployed based on factor bets like Momentum and Value, relying on research that ascribes long term equity returns to them. Momentum has been outperforming Value for several years – since the peak in oil in 2014, which partly explains negative sentiment towards the energy sector since then.

During the summer, the difference in relative performance jumped sharply, leading to the recent correction. Perhaps slowing global growth has caused a reassessment of high fliers. It increasingly looks as if trade tariffs, which are simply import taxes, are spreading a chill across the world economy.

Momentum has slipped 9% against Value since August 29. This is an unusually fast correction. In 2016, Value outperformed Momentum by 10%. This lifted MLPs, with the Alerian MLP Index returning 18% that year.

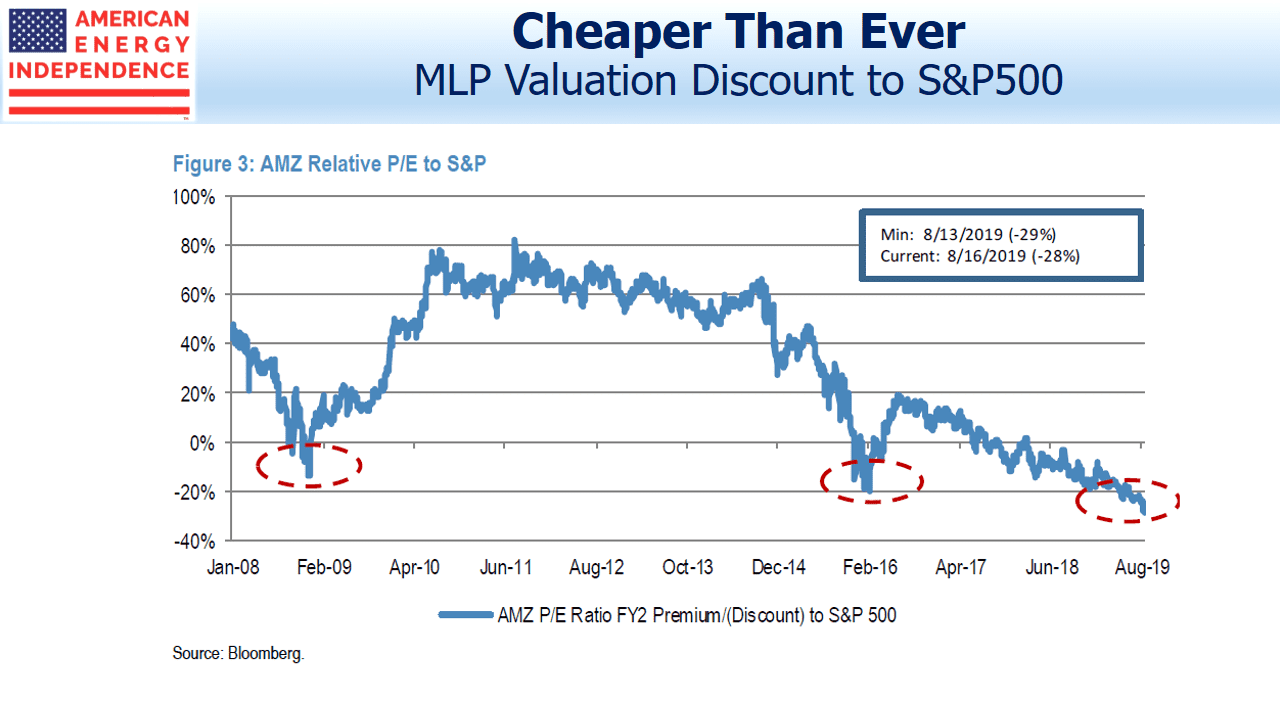

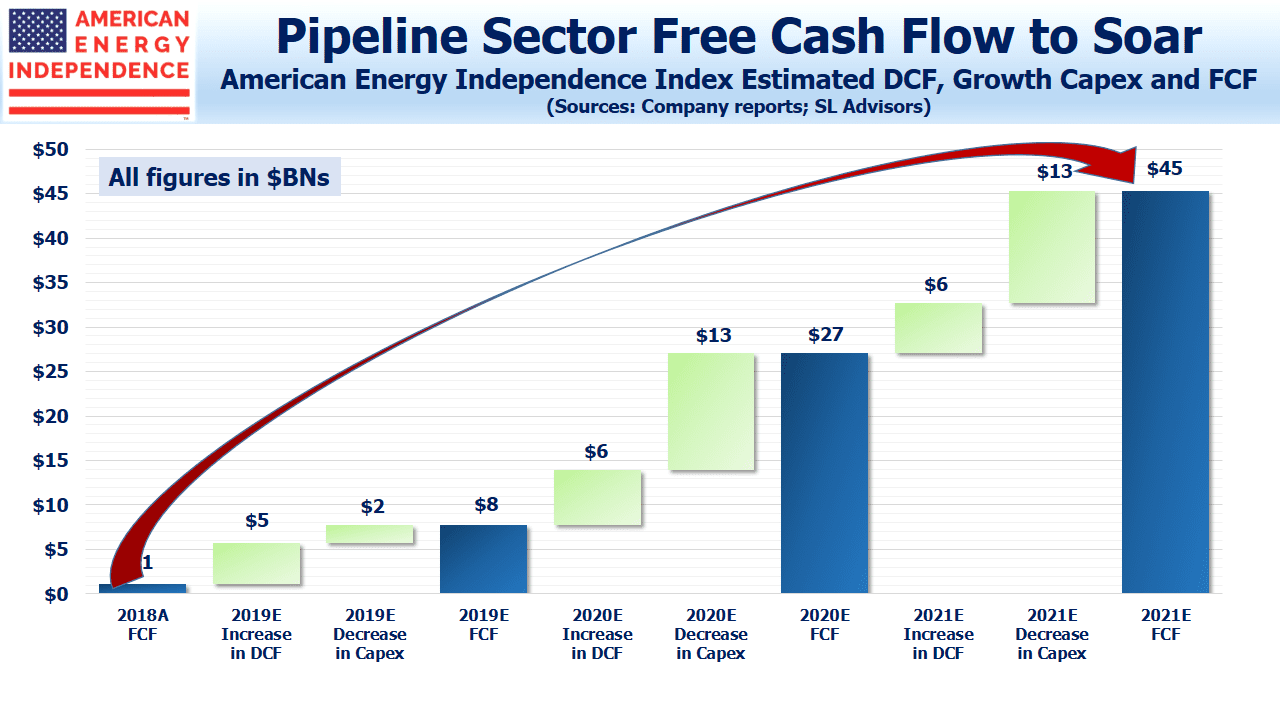

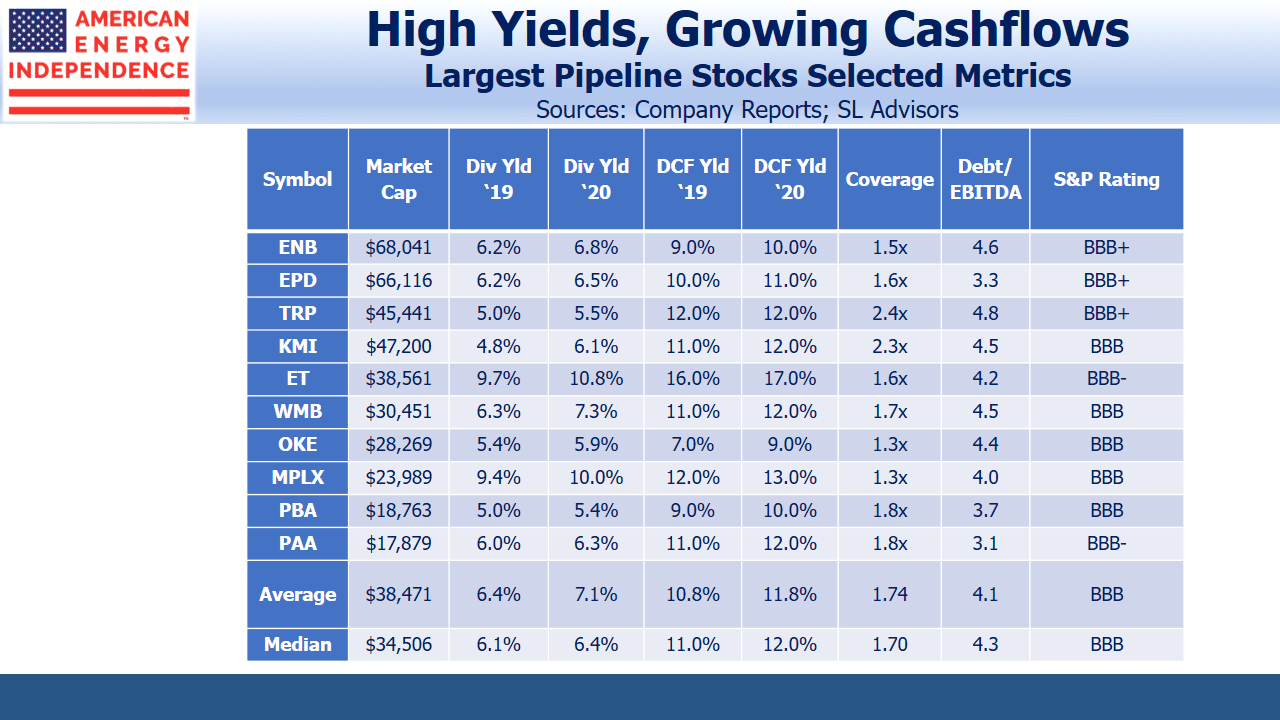

If Value starts to regain favor, investors will find plenty of cheap stocks among midstream energy infrastructure.

Blackstone — Tallgrass

Two weeks ago Blackstone offered to acquire the 56% of Tallgrass Energy (TGE) it didn’t already own. The $19.50 per share price was below the $22.47 at which Blackstone had bought 44% earlier this year. But the sideletter allowing TGE management to sell at $26.25, regardless of the price received by other TGE shareholders, is unethical.

As we noted in Blackstone and Tallgrass Further Discredit the MLP Model, the deal exposed an ethical gulf between the prevailing standards at asset managers and the public companies we invest in. If we treated our investors the way TGE proposes to, our careers would be brief.

What’s surprising is the silence among other TGE investors as well as sell-side analysts. Few wish to risk upsetting either Blackstone or Tallgrass by pointing out the obvious. This failure to speak out is itself a disservice to clients.

Although there have been no further announcements since the proposal was made public, TGE’s stock has edged above the deal price. Some traders are betting that Blackstone will sweeten its offer. If that turns out to be the case, we’ll be happy to have helped.

We are invested in TGE