Bond Buyers Should Buy Pipeline Stocks

Yields on McDonalds’ Euro-denominated bonds recently joined European sovereign debt in negative territory. It’s a headline writers dream (juicy burgers, not yields…customers and investors pay to do business, etc).

$17TN in publicly traded debt now yields less than zero – 30% of the entire investment grade market. Debates rage about what this means. Bond investors are not accused of being analytically weak – something bad must be over the horizon. As mentioned before, we’re contemplating the idea that such a stubborn retention of fixed income investments reflects a degree of risk aversion towards stocks, for fear of a sharp fall. The searing memories of the financial crisis are within the careers of most market participants. Stocks are always vulnerable to a big sell off. But the preponderance of caution reflected in the scramble for low-risk yet yield-less bonds suggests speculative fever is not rampant. In this view, stocks are cheap.

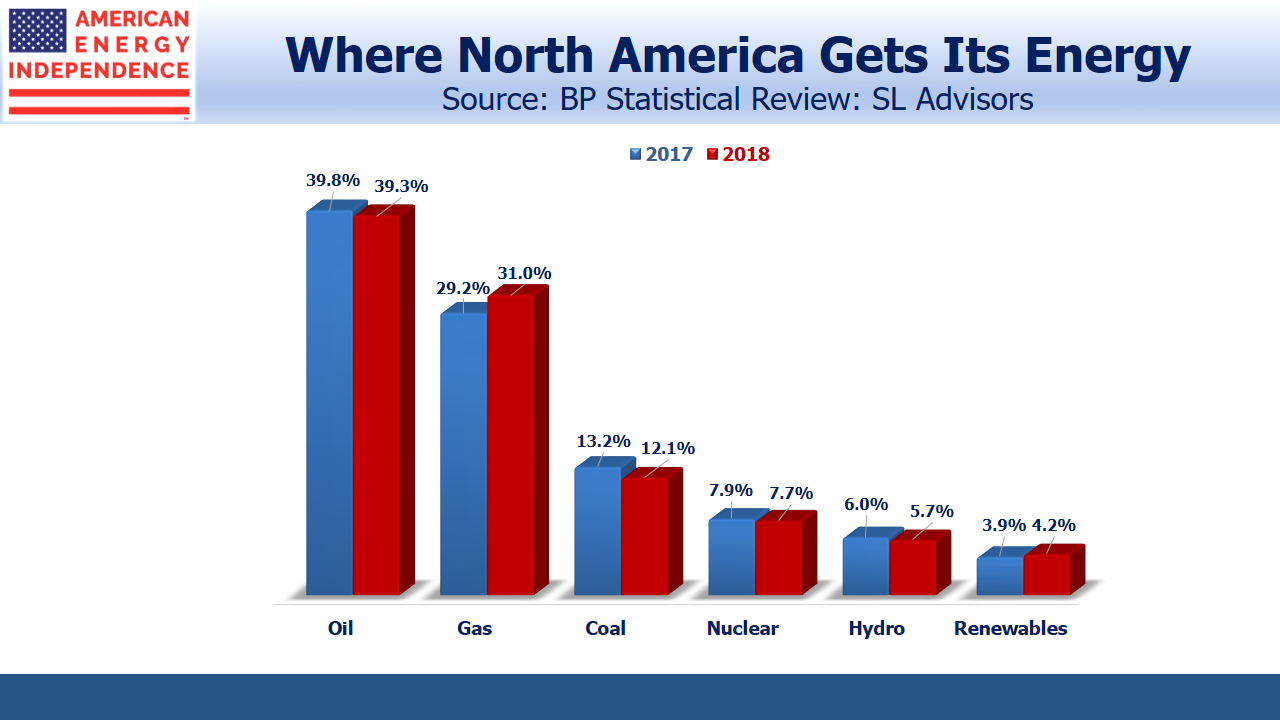

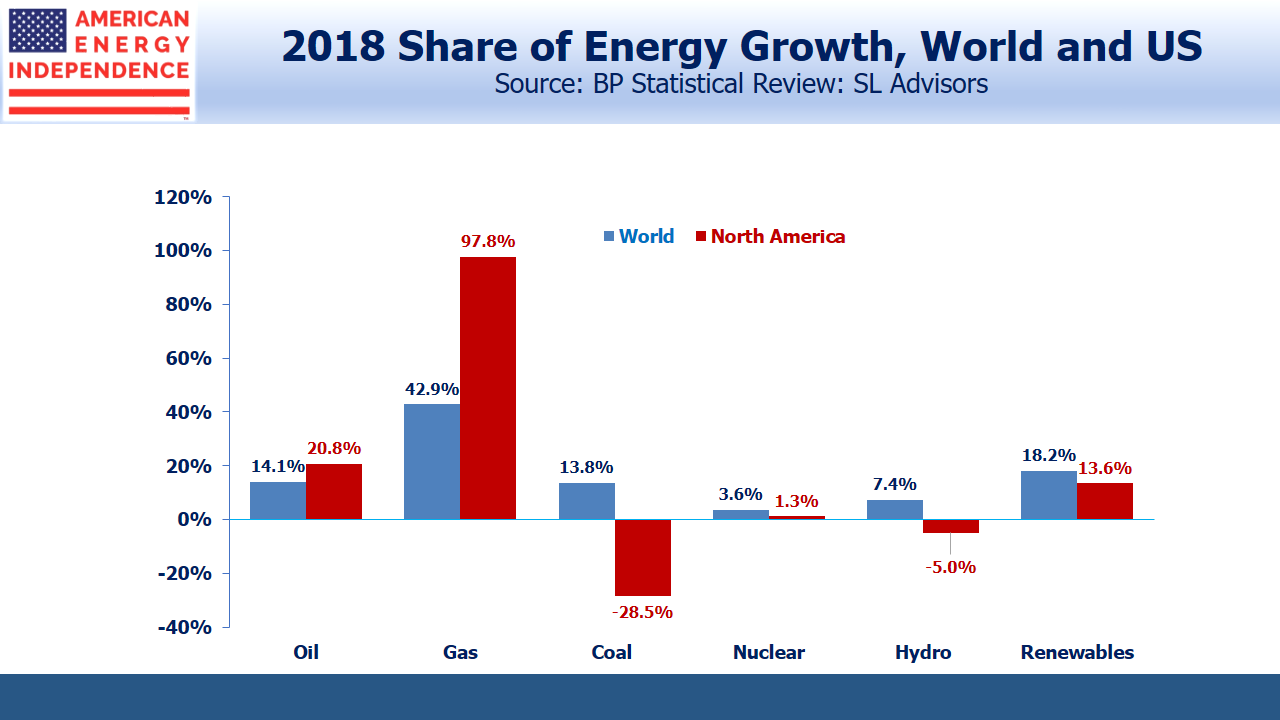

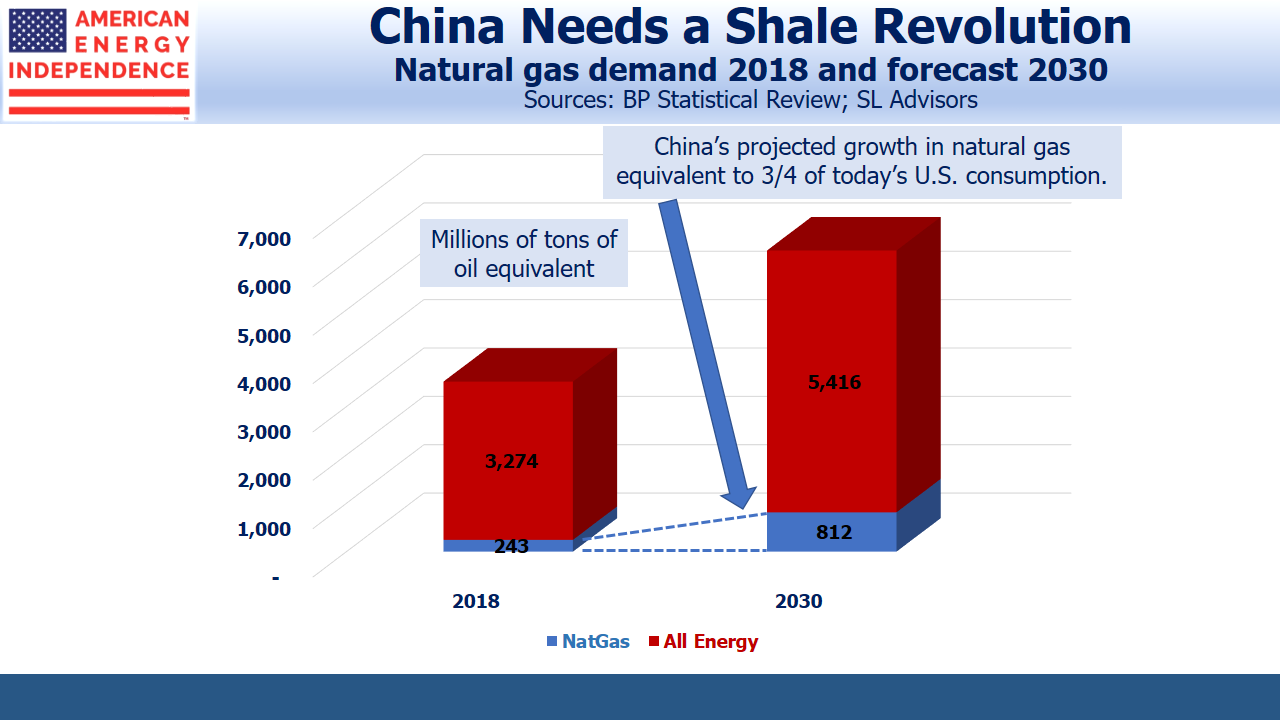

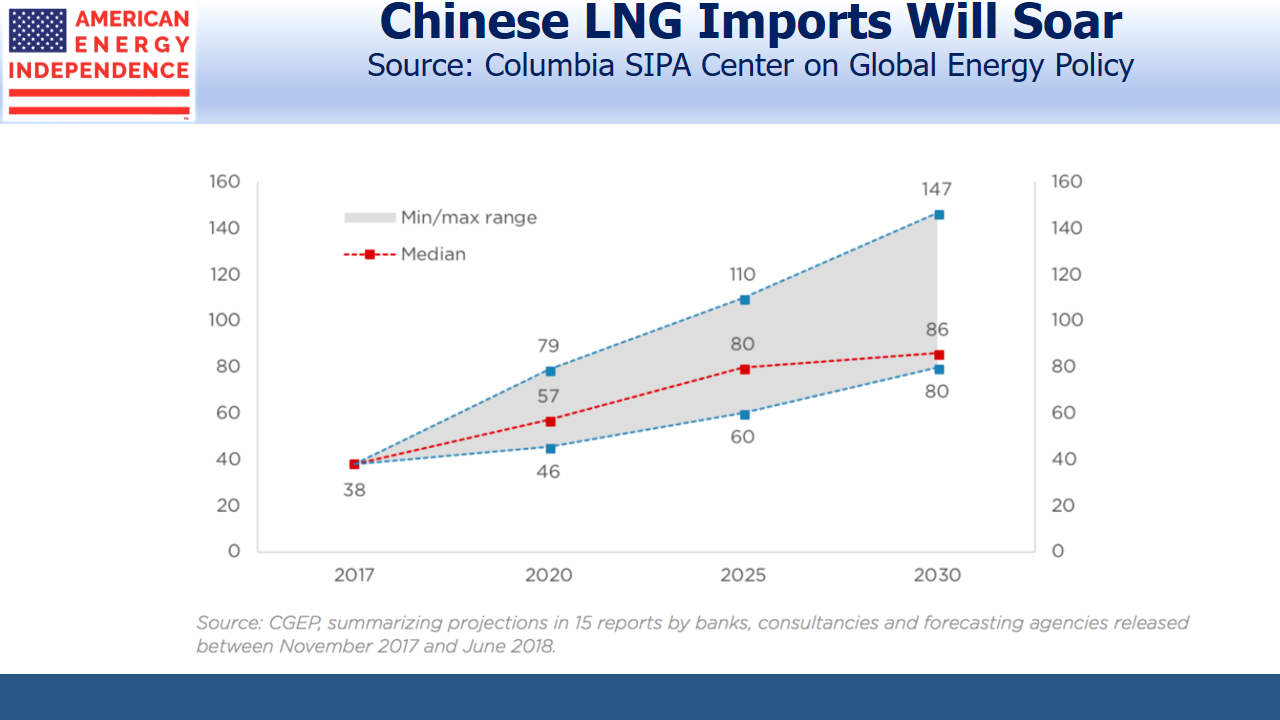

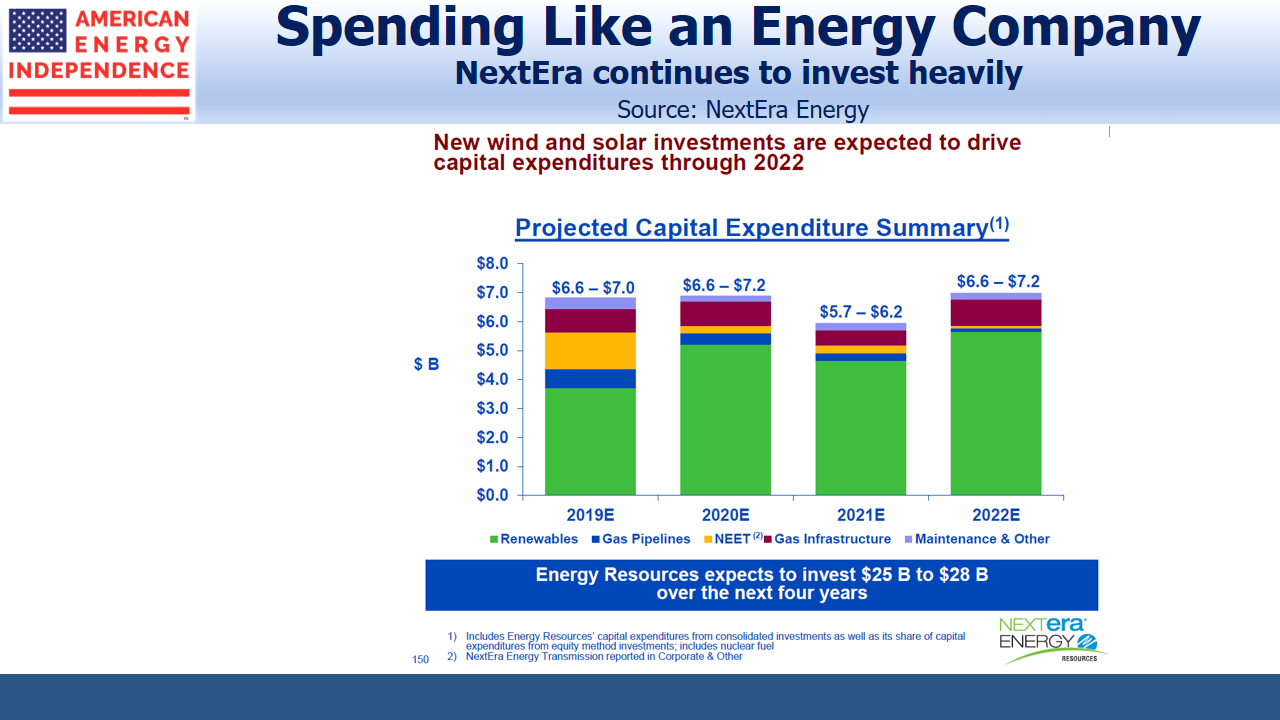

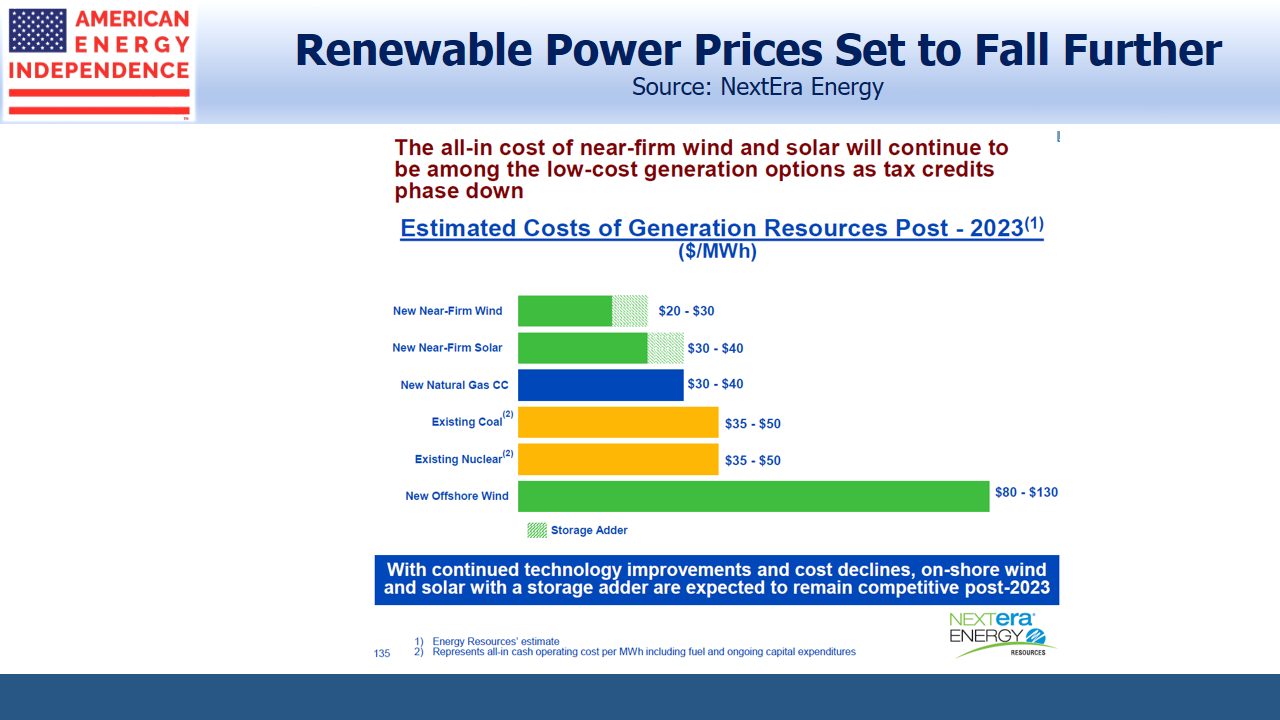

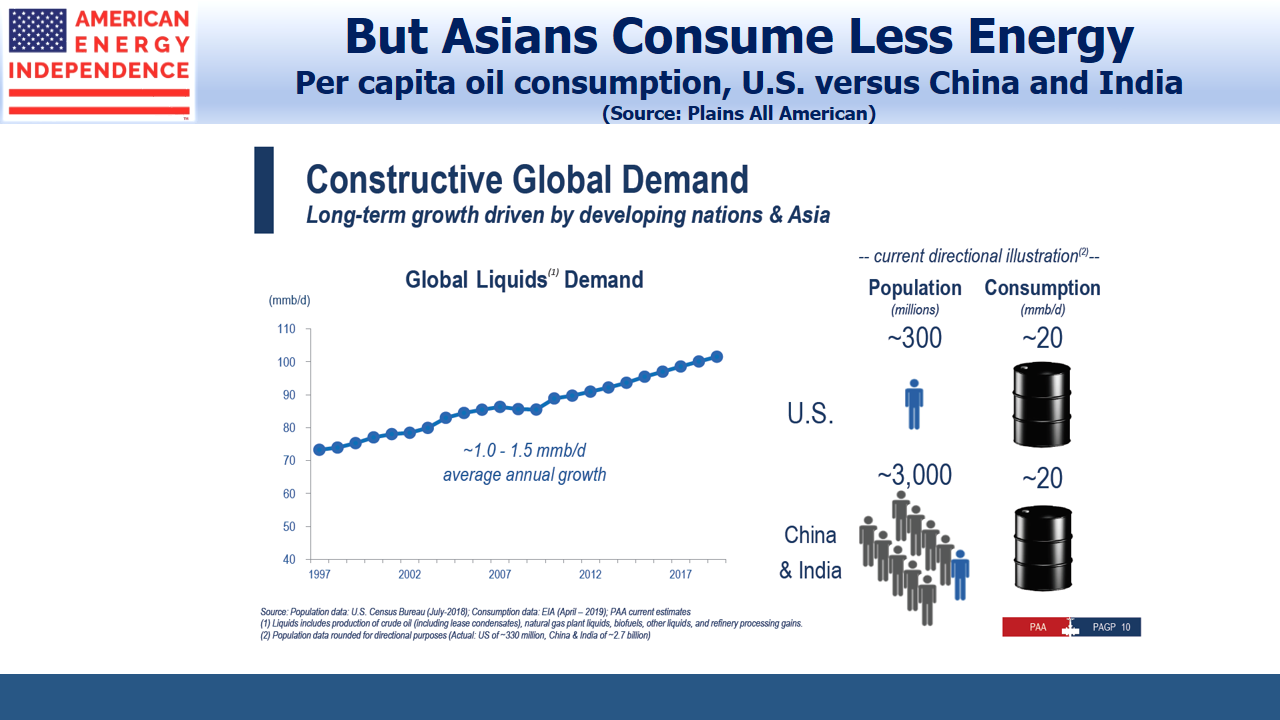

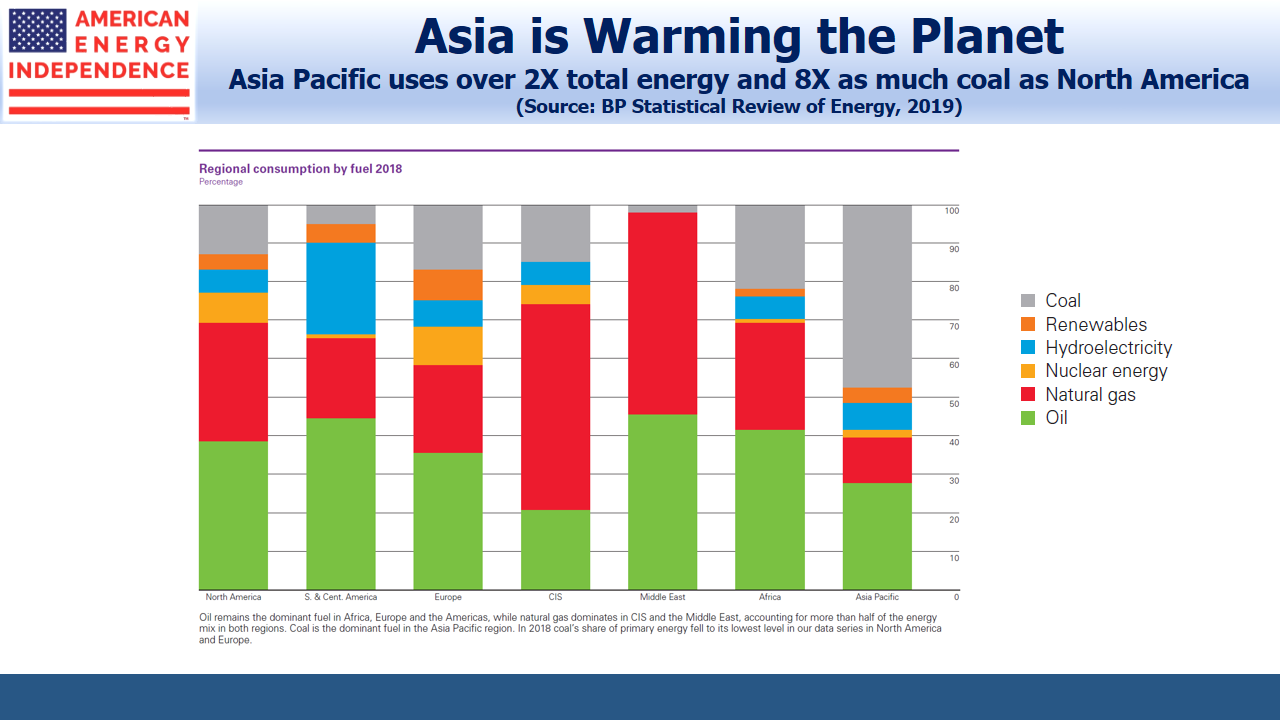

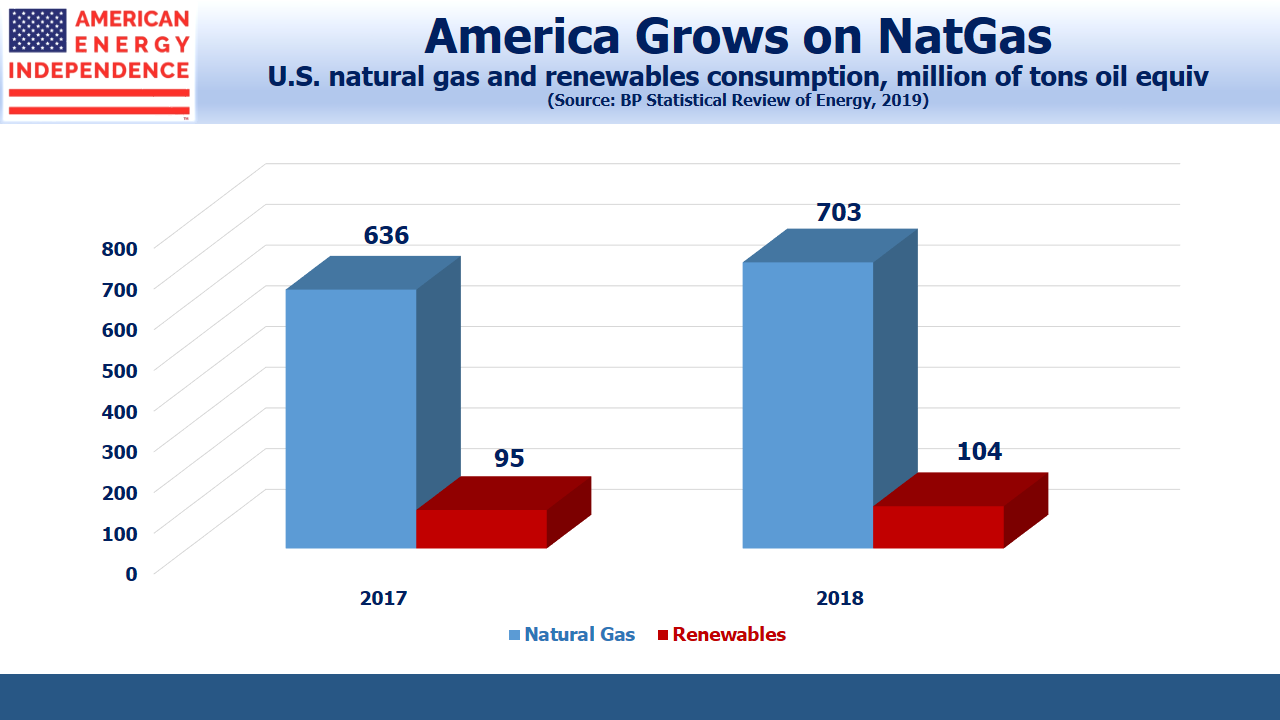

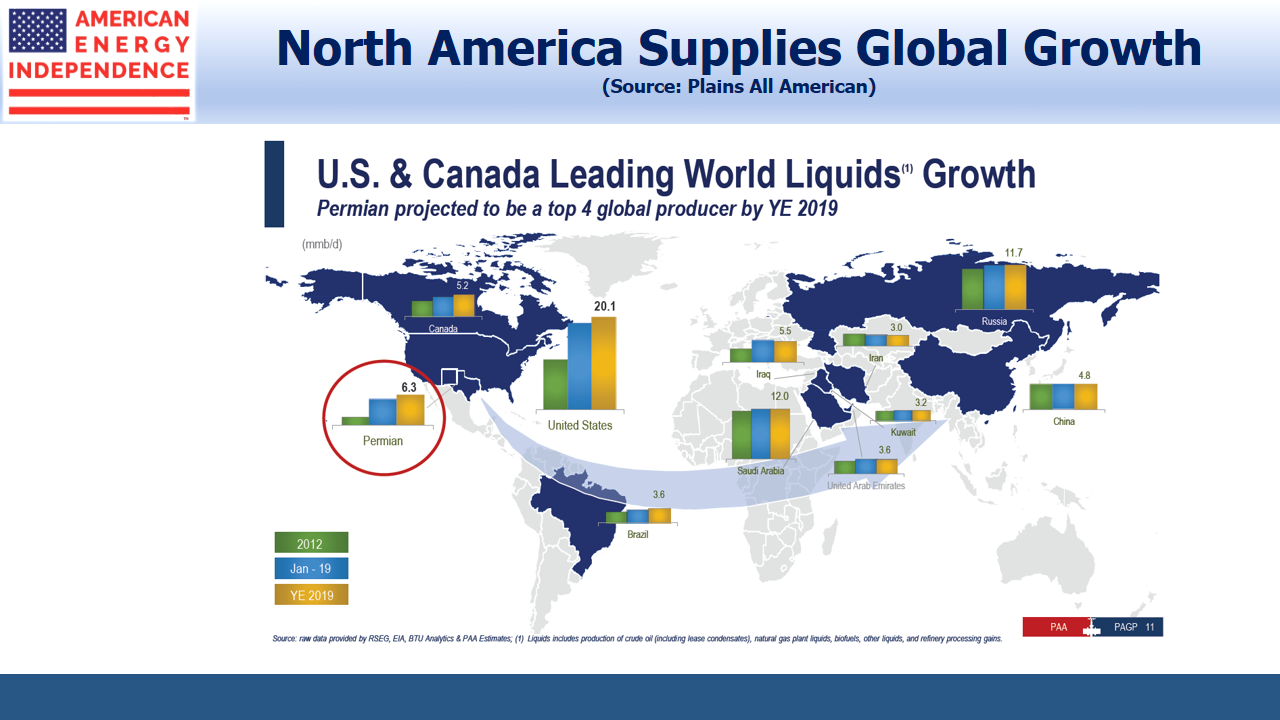

The energy sector has provided unattractive risk/return of late. It’s why it’s so cheap. One of the reasons for poor sentiment could be climate change. 82% of the world’s energy comes from fossil fuels, and the average of serious 20-year forecasts sees this at around 80% in 2040. Reading articles on renewables can consume much of a day, every day, while those expecting the 82% share to stay roughly the same are a rare breed.

If equity valuations on midstream energy infrastructure stocks reflect a widespread belief that oil and gas pipelines will soon be as useful as a VHS recorder, bonds issued by these same companies should offer commensurately high yields.

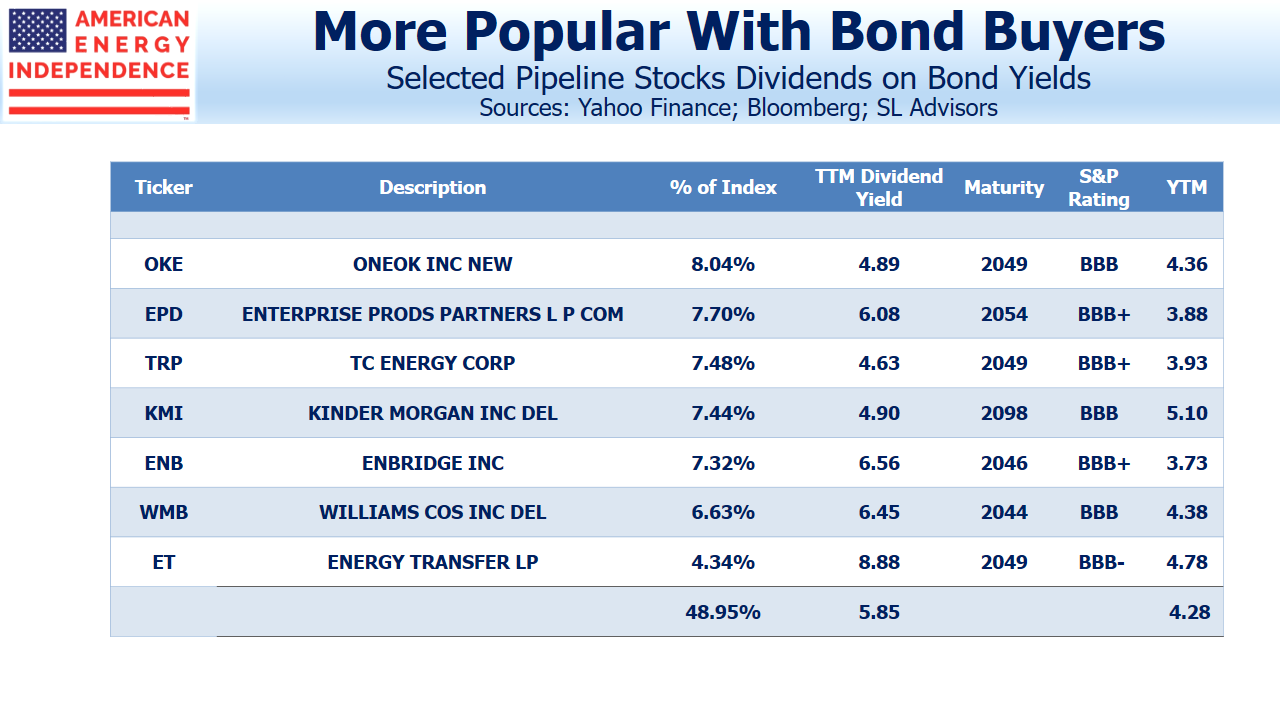

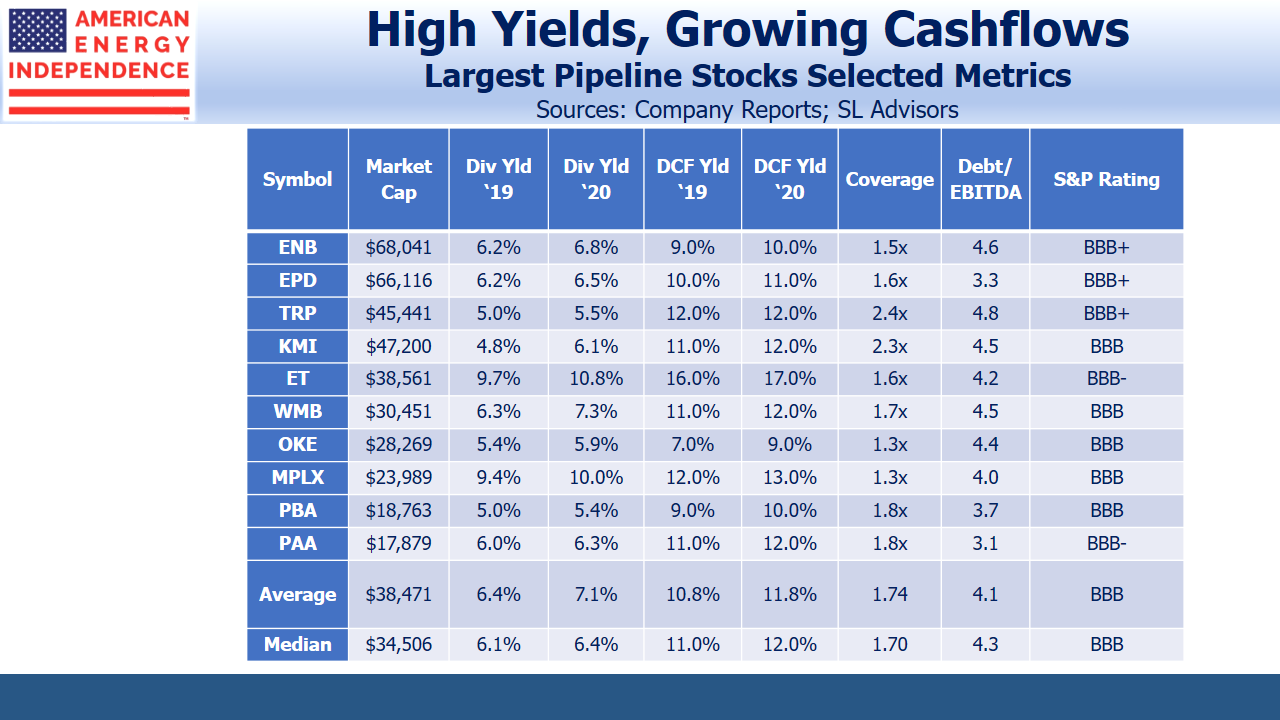

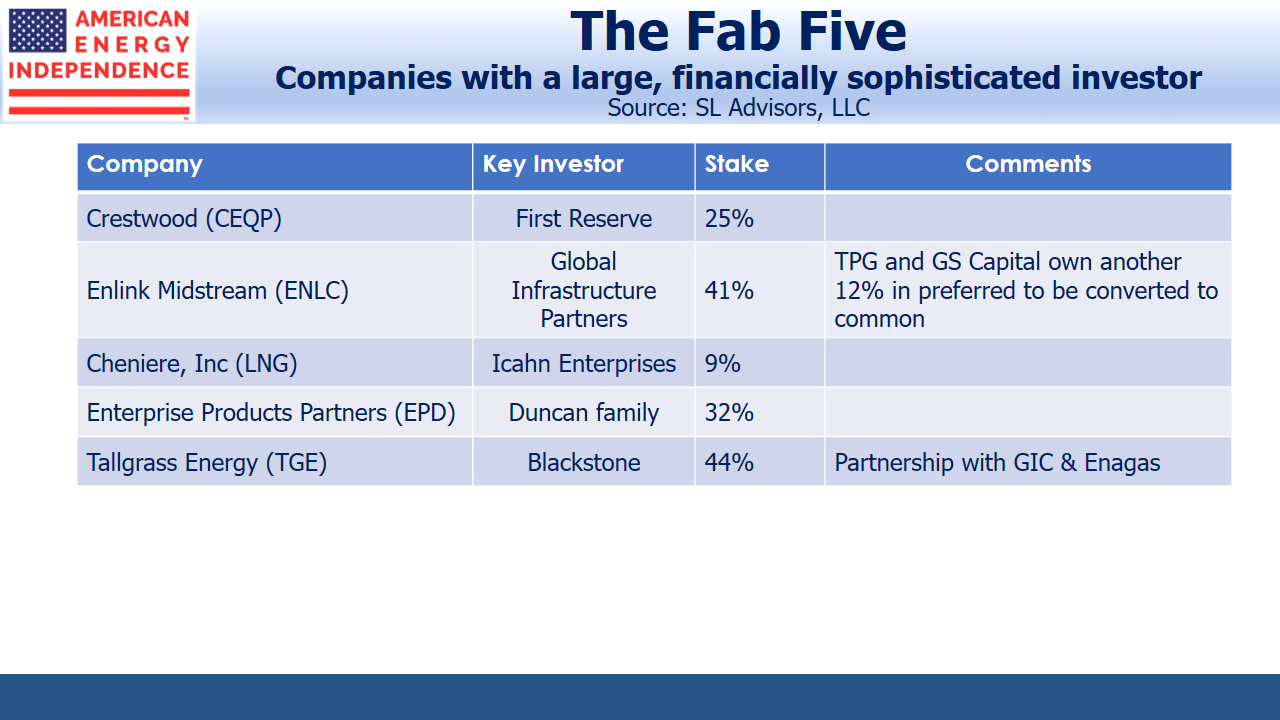

But they don’t. A review of yields on the investment grade bonds of U.S. issuers in the American Energy Independence Index averages 3.7% (using the weights of the index). Although yields of any kind are hard to obtain nowadays, the 3.9% yield on 2054 bonds issued by Enterprise Products Partners (EPD) suggests a high expectation of being repaid in full. This in turn requires pipelines and related infrastructure to maintain their critical role in America’s energy supply for at least another four decades. EPD’s stock yields over 6%. Its distribution is growing and buybacks are likely. Try and conceive a scenario in which the holder of the 2054 bonds will, over any plausible investment horizon, do better than the equity investor.

Kinder Morgan (KMI) has bonds maturing in 2098, in effect perpetual debt, yielding 5.1%. Although this is modestly higher than the stock’s 4.9% dividend yield, next year’s expected 25% hike will fix that. Although the 2098 bond issue is a tiny $26MM, they have $33BN outstanding, much falling due after 2040. The holders of KMI 2098 bonds no doubt congratulate themselves for doing better than investing in French energy giant Total (TOT), who recently issued perpetual Euro debt at 1.75% (see Blinded by the Bonds). But if they like KMI’s 80 year bonds, they’d have to prefer the equity.

The investment grade issuers in the table represent half of the American Energy Independence Index. Their long dated bonds yield 4.3% — profligate by today’s standards, but nonetheless too low to reflect anything other than confidence of full repayment over the decades ahead. The holders of these bonds must regard equity buyers as having abandoned all reason in allowing dividend yields to drift so high.

If fixed income buyers like midstream energy infrastructure, eventually equity buyers will find reason to follow.

We are invested in EPD and KMI.

SL Advisors is the sub-advisor to the Catalyst MLP & Infrastructure Fund. To learn more about the Fund, please click here.

SL Advisors is also the advisor to an ETF (USAIETF.com).