Pipeline Sector Extends Outperformance

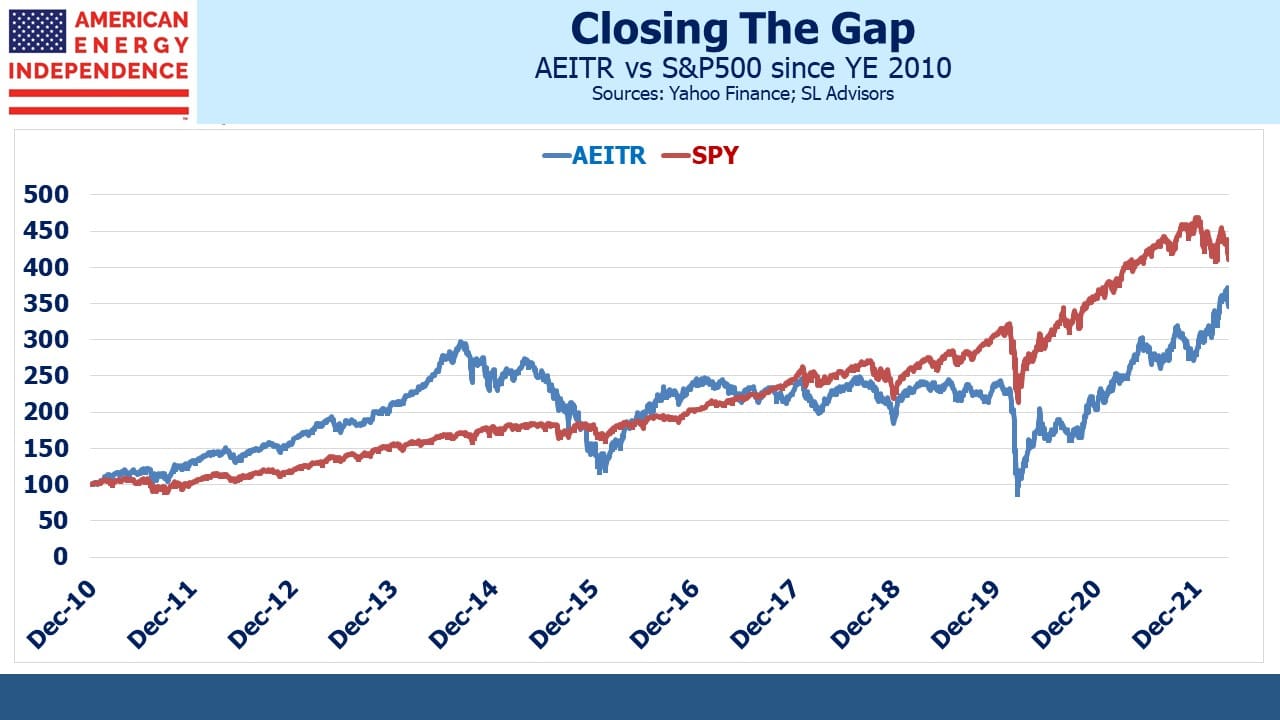

The continued rally in the energy sector is steadily lifting past performance ahead of the S&P500 over multiple timeframes. The American Energy Independence Index (AEITR) now has a higher annual return than the S&P500 over the past one, two and three years. Even over five years the performance gap is closing. The 12.3% pa return on the S&P500 is 3.1% ahead of the AEITR. On the Covid low (3/18/20), the AEITR five year trailing return was –19.2% pa, 23.9% worse than the S&P500. It was a dark moment indeed for pipeline investors, and especially so for those focused on MLPs where the carnage was even worse.

The subsequent recovery has produced some striking relative performance. The one and two year trailing performance figures cause some potential investors to question whether such a move will assuredly be followed by a collapse.

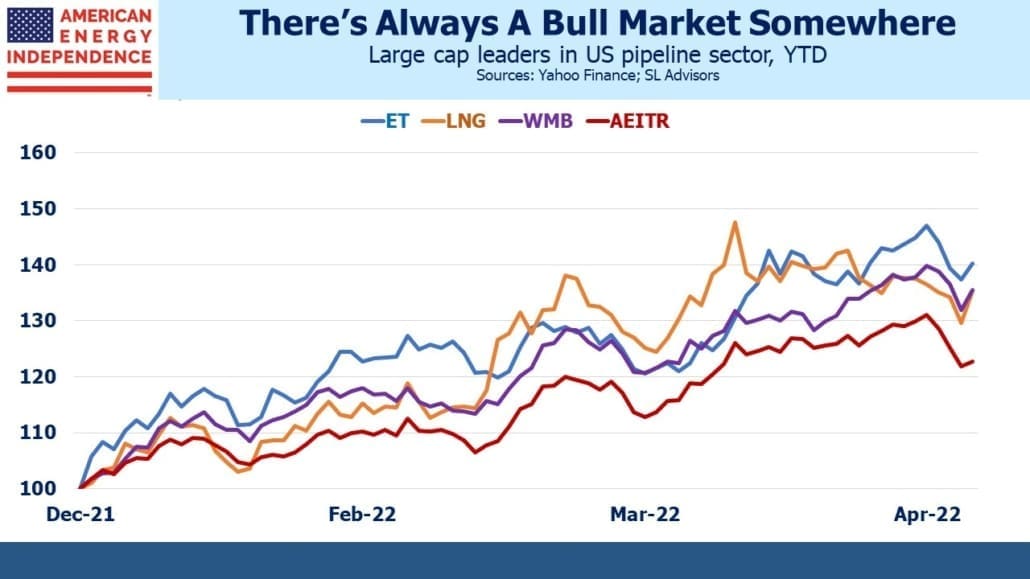

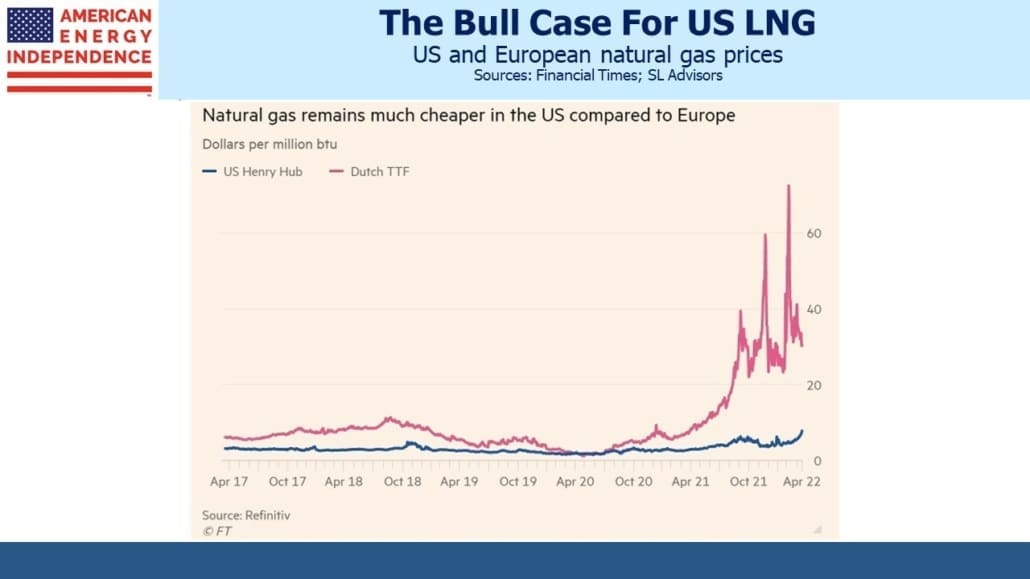

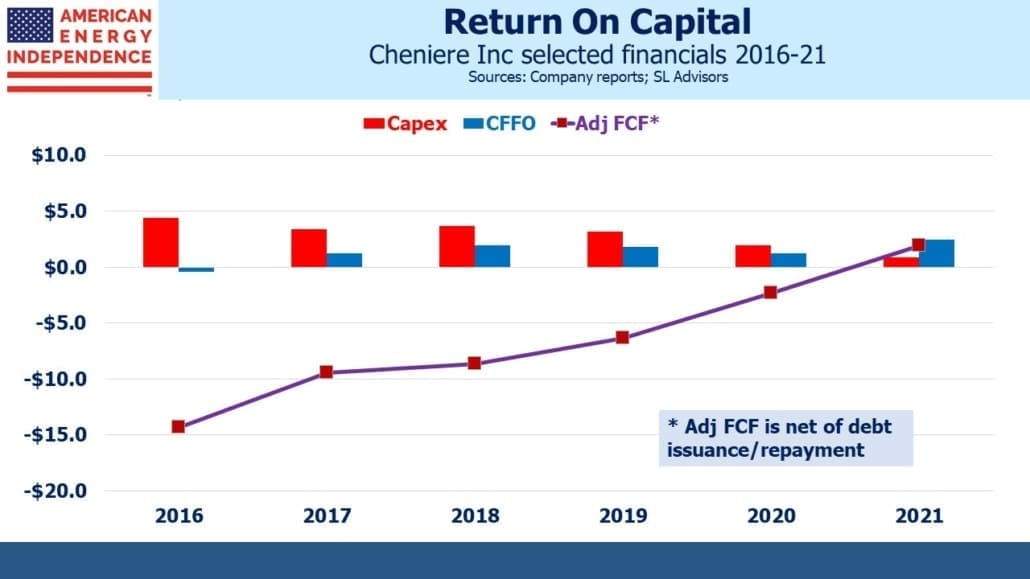

The fundamentals remain very good. 1Q22 earnings generally beat expectations, in some cases (ie Cheniere) by a huge margin. Financial discipline continues to constrain growth capex, aided by pipeline protesters whose efforts further dissuade spending on new projects. Hug a protester and offer to drive them somewhere.

The Covid recession and recovery dominate recent performance history. But it’s worth remembering that the pipeline industry had already shifted away from spending for growth in favor of increasing free cash flow before that. By late 2019, pre-Covid, we felt the sector was poised to outperform because the growth years and MLP distribution cuts of the Shale Revolution had alienated so many investors.

Two months ago, the pre-Covid return (ie from 12/31/2019) on the AEITR moved ahead of the S&P500. As of Thursday, the AEITR is 8.3% ahead of the market. Surging inflation and Europe’s sudden desire for energy security are two important tailwinds for energy stocks. But the sharp drop and quick recovery that Covid inflicted on the pipeline sector is looking increasingly aberrant. It will always be part of the sector’s history. Becoming comfortable that it won’t repeat is a hurdle facing many potential new investors.

Closed End Funds (CEFs) have a longer history of providing MLP exposure to retail clients than even the deeply flawed Alerian MLP ETF (AMLP, see MLP Funds Made for Uncle Sam). For example, the Cushing MLP & Infrastructure Total Return Fund (SRV) sports an inglorious fifteen year history of relentless capital destruction. It now trades at less than one tenth of its IPO price. In 2015 we were moved to note its sorry eight year performance of delivering less than a quarter of the return of its benchmark (see An Apocalyptic Fund Story). Although consistent performance has rendered its diminutive size ($70 million AUM) no longer a significant source of revenue to manager Swank Energy Income Advisers, it still serves to warn CEF investors of the damage leverage and poor management can inflict.

CEFs were generally not a big factor in the Covid bear market, but they did play an outsized role in the MLP collapse, which hurt the entire midstream sector. Operating a single sector fund with leverage reflects an opinion that the companies in that sector should be operating with more debt than they currently do. In effect, it’s a rejection of the collective wisdom of all the CFOs and rating agencies that have arrived at the prevailing capital structure in use.

Since the stocks within a sector will tend to be highly correlated with one another, there’s little diversification benefit which might otherwise justify the increased risk profile. Single sector closed end funds use leverage to increase the dividend they can pay. But maintaining that leverage requires them to add to their holdings in a rising market – and to reduce them in a falling one.

When MLP prices collapsed in March of 2020, MLP CEFs had no choice but to delever, which required selling. They exacerbated the fall in prices for the pipeline sector.

The reason investors shouldn’t expect a repeat is because the consequent value destruction left all the MLP CEFs smaller. They’re no longer managing as much money, because of locked in losses, so wouldn’t have as much to sell even if we endured a repeat of March 2020. The managers of sector-specific CEFs with leverage combine poor judgment with hubris. They include Goldman Sachs, Tortoise, First Trust and Swank.

Many MLP CEF holders who hung on in the belief that what falls so far must surely rebound will have been disappointed. The 17 MLP CEFs listed on Nuveen’s website are on average still down 37% from their level at the end of 2019, pre-Covid. The AEITR has fully recovered its losses with an 18.5% pa positive return.

The two lessons are: (1) don’t invest in single sector CEFs because the leverage will eventually create permanent losses, and (2) because MLP CEFs provided evidence of #1 in 2020, they can’t repeat. So prospective investors in midstream energy infrastructure can regard the worst of the March 2020 brief collapse in pipeline stocks as unlikely to repeat.

We have three funds that seek to profit from this environment:

Energy Mutual Fund Energy ETF Real Assets FundPlease see important Legal Disclosures.