4Q Earnings Wrap

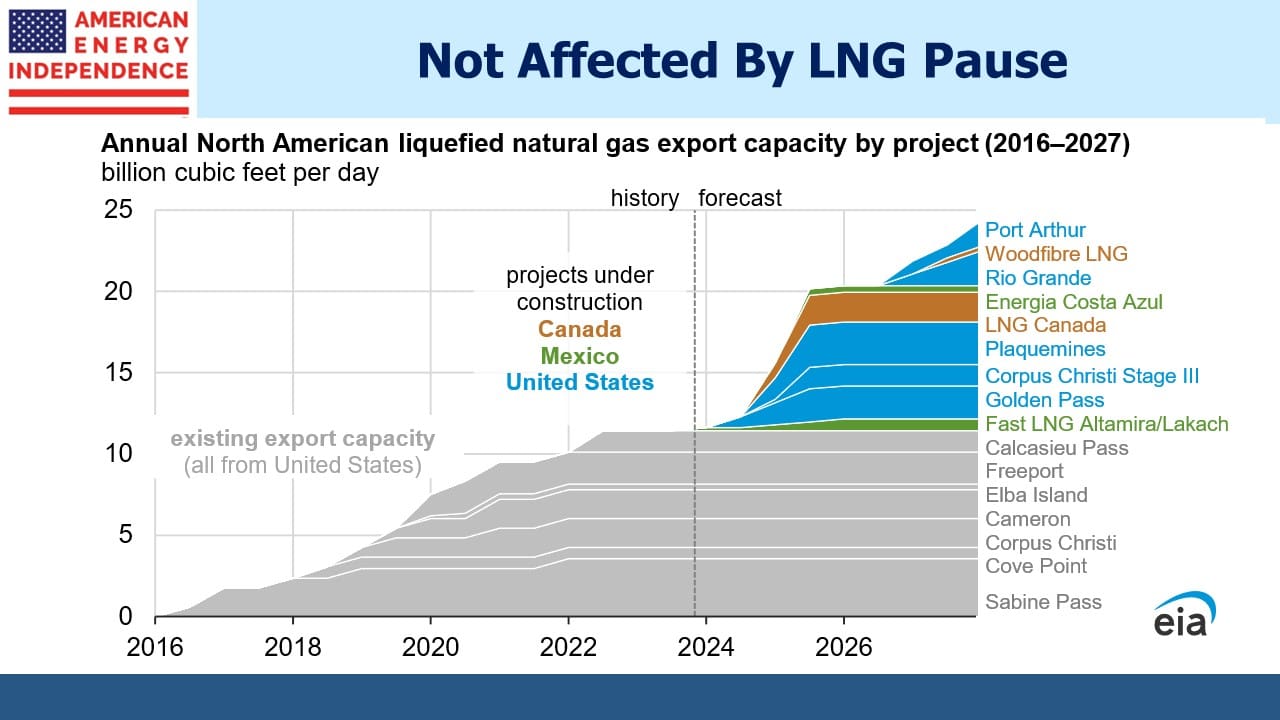

Earnings for 4Q23 are almost complete. Most companies came in at or a few per cent ahead of market expectations. Cheniere (CEI) beat sell-side estimates by 11%, continuing a remarkable run. They are targeting a 1:1 ratio between buybacks and debt reductions and based on their long run desired share count should be retiring 12-13% of outstanding shares over the next few years.

CEI’s FY2023 EBITDA came in at $8.77BN. The stock dipped last week as 2024 EBITDA guidance came in a little below expectations at $5.5-6.0BN. Last year they benefitted from large regional price differences in natural gas on the portion of their LNG capacity not committed under long-term agreements. They have not assumed the same opportunity this year. Despite CEI’s flat stock performance over the past year, JPMorgan and Wells Fargo continue to rate them Overweight. It’s one of our bigger holdings.

Plains All American (PAGP) came in 10% ahead of expectations as their crude oil and Natural Gas Liquids segments both reported strong results. They increased their distribution by 19%.

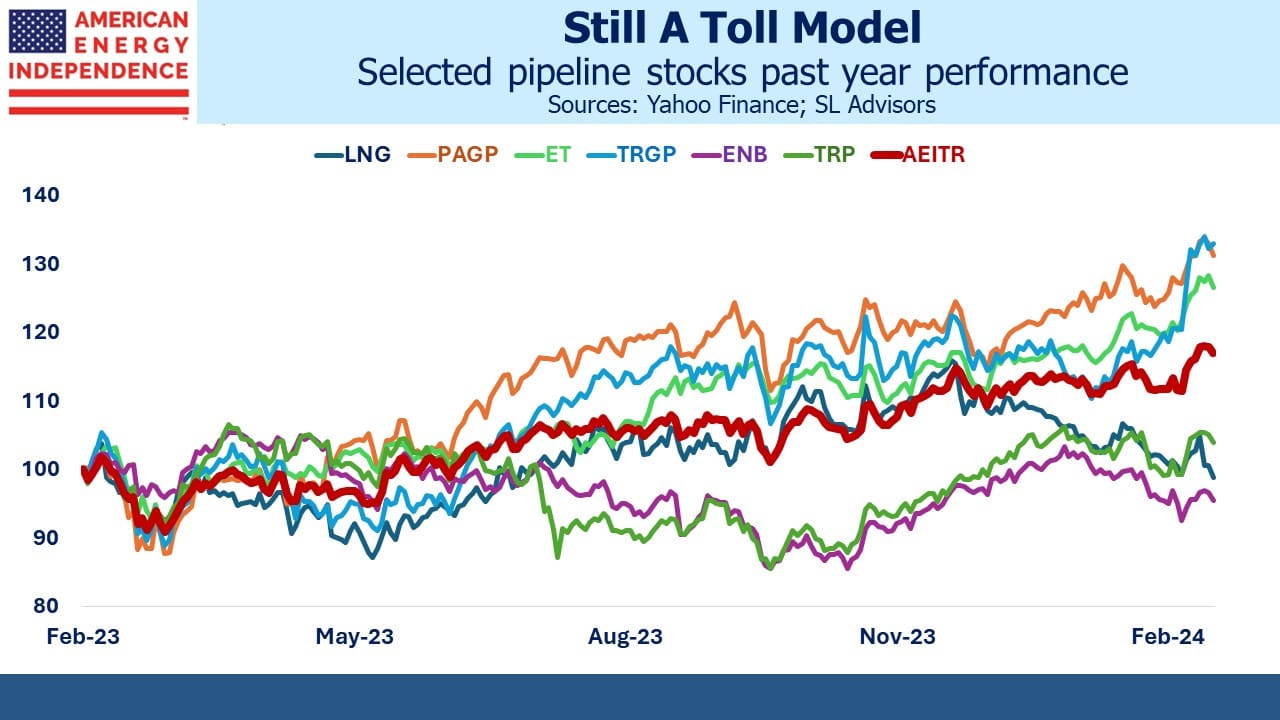

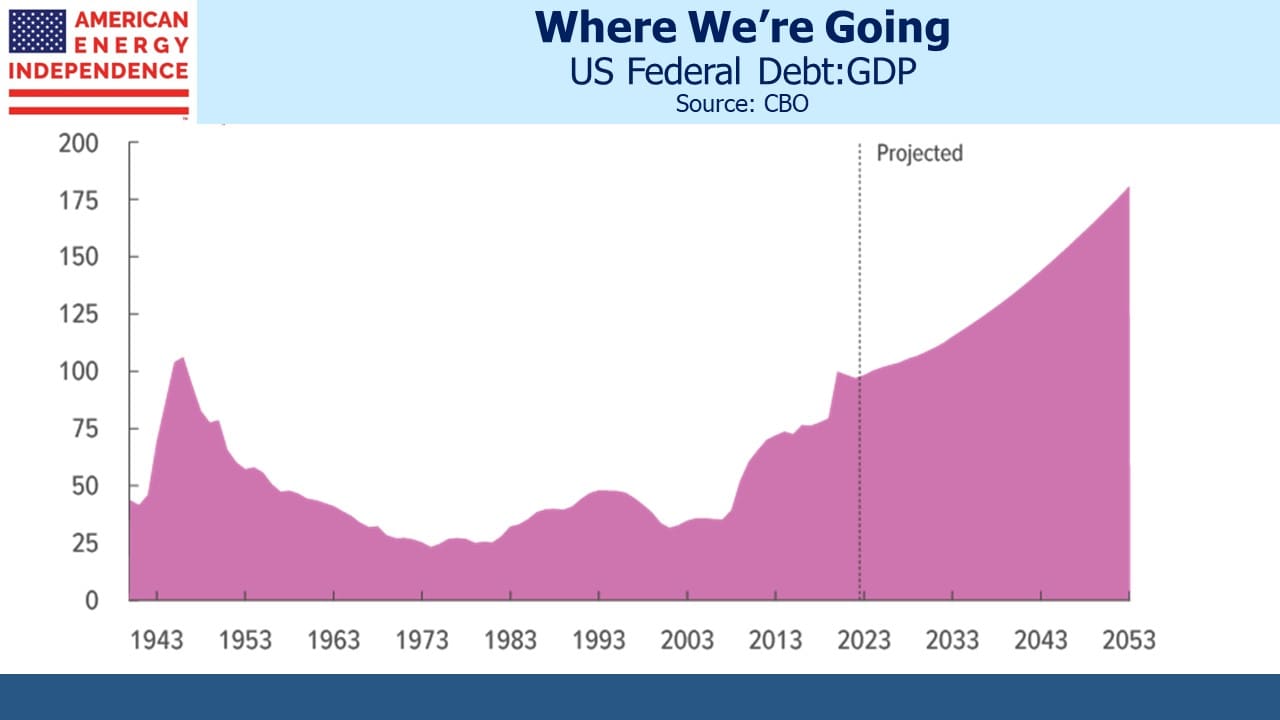

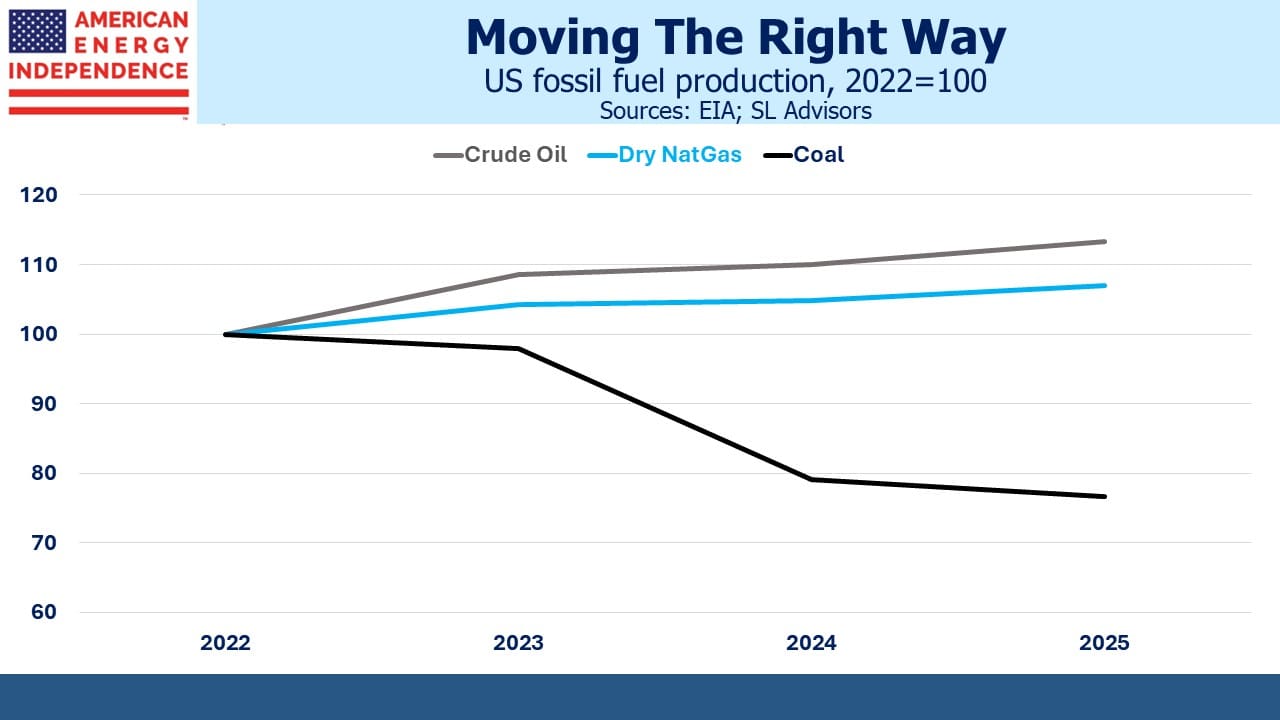

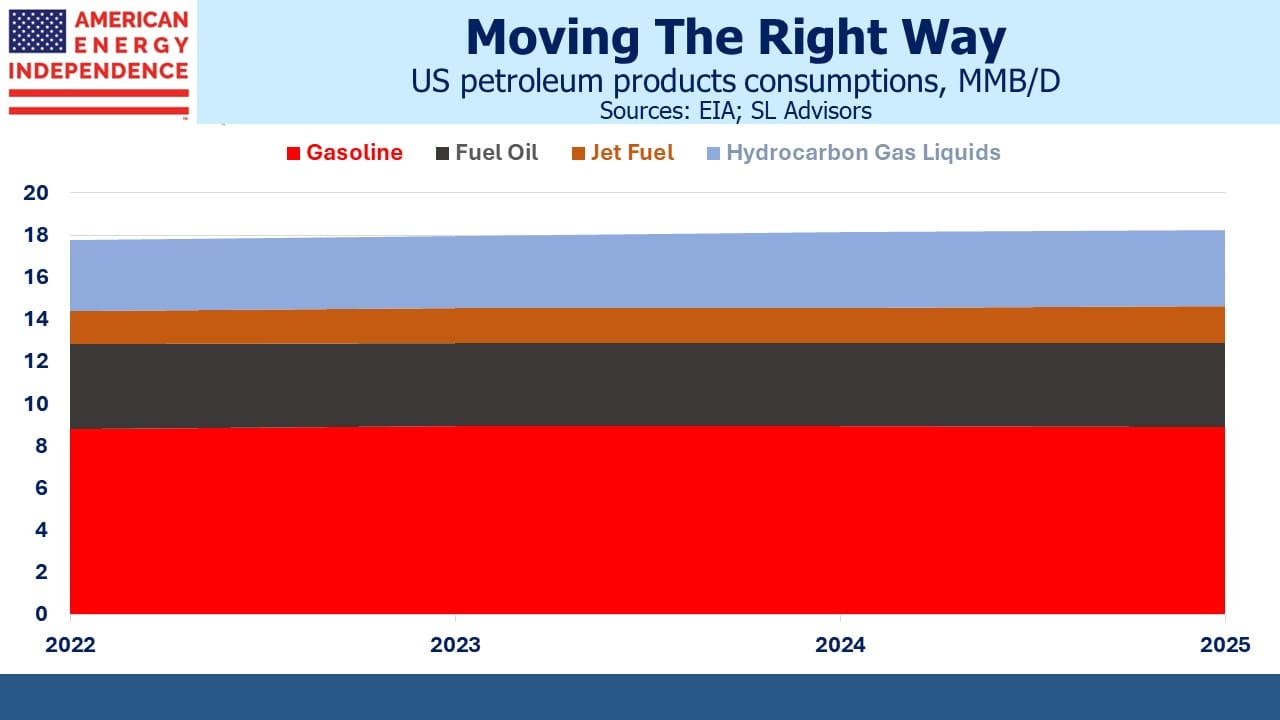

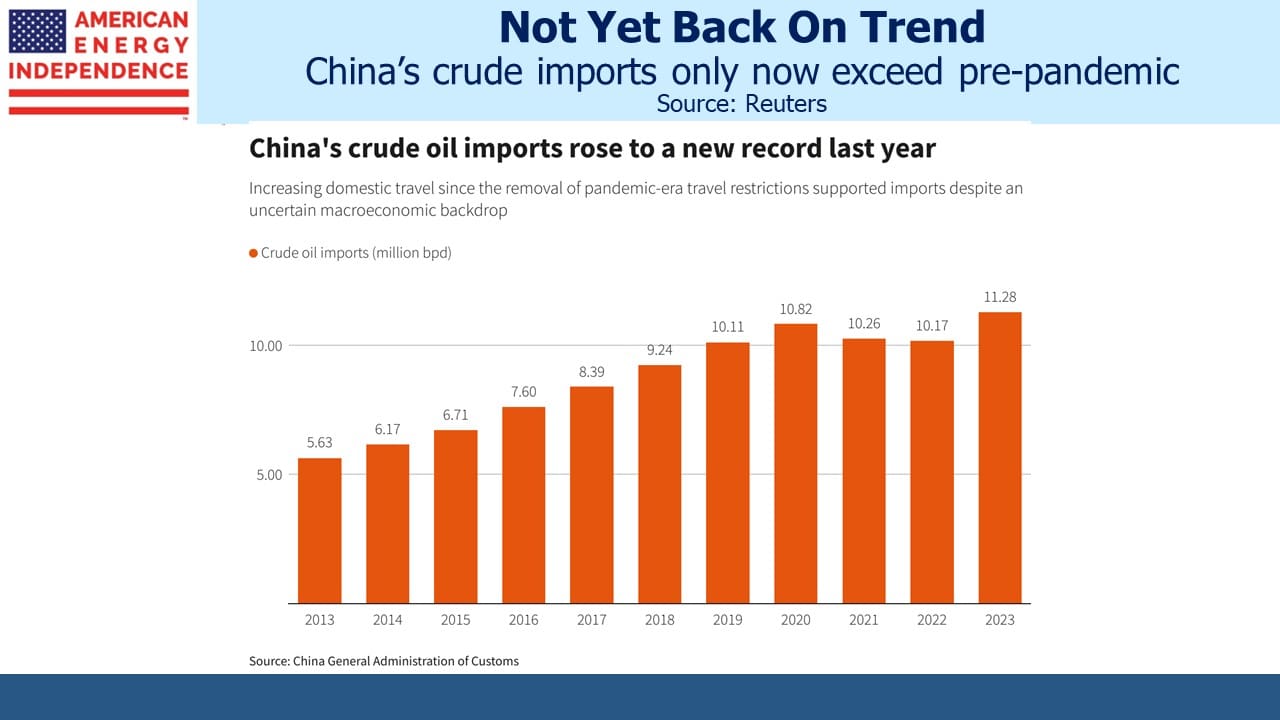

PAGP stock has performed strongly in the past year, +31% versus the American Energy Independence Index (AEITR) at +17%. We tend to underweight crude oil businesses in favor of natural gas where we believe the long-term growth prospects are more assured. Nonetheless, the softening of US demand for electric vehicles will encourage the view that US crude oil demand is not going to fade away.

Energy Transfer’s (ET) 4Q EBITDA came in close to consensus at $3.6BN. However, 2024 EBITDA guidance was slightly below expectations while capex was somewhat higher. The stock remains attractively priced in our view, and any disappointment over the guidance was short-lived. It’s up 26% over the past year, including that high dividend which currently yields 8.4% and is covered 2X by Distributable Cash Flow (DCF). ET is rated Overweight at JPMorgan and Wells Fargo.

Targa Resources (TRGP) is another strongly performing stock, +33% over the past year including its low dividend which currently yields 2%. TRGP is well positioned to transport NGLs from the Permian to export terminals on the Gulf coast, providing an integrated service to customers with multiple opportunities to add value.

JPMorgan expects 9%+ EBITDA growth this year and next. With management committed to returning 40-50% of cash from operations to shareholders via dividends and buybacks, there is plenty of room for TRGP to increase its quarterly payout.

The Canadians have been lagging the sector because of market concerns about their capex. Enbridge’s (ENB) C$19BN acquisition of three utilities from Dominion last year wasn’t well received. They’ve raised 85% of the funds needed through debt, equity and asset sales. ENB stock is -4% over the past year, meaningfully underperforming the sector. Their 7.8% yield is 1.4X covered by DCF. Analyst opinion is mixed – JPMorgan is Overweight while Wells Fargo is Underweight.

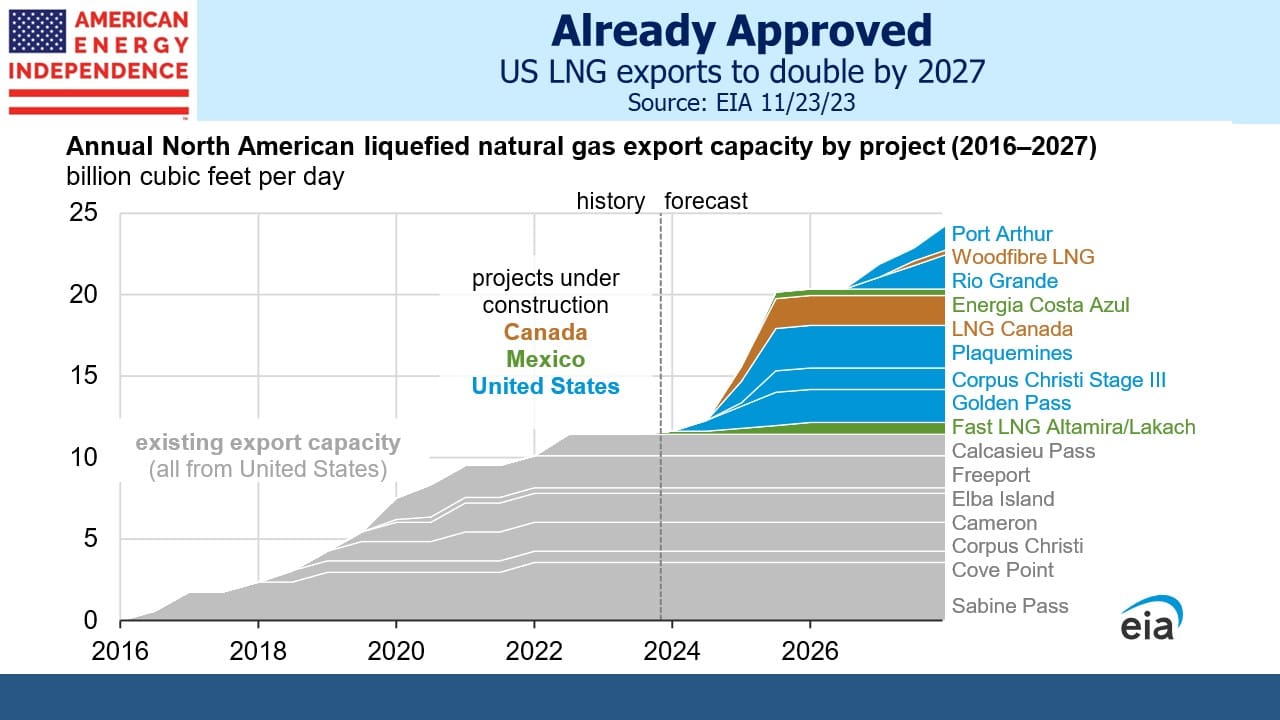

TC Energy (TRP) has also lagged the sector, +4% over the past year. Their capex has been higher than investors would like over the past couple of years, but projects are nearing completion and spending is coming down. Coastal GasLink was completed late last year and will provide natural gas to LNG Canada’s export terminal in Kitimat, BC for export to Asian customers. The Southeast Gateway project will connect customers in Mexico with domestic supply. It is scheduled to be completed next year. This year capex is forecast to be C$8-8.5 and closer to C$6BN next year. Their 7% dividend yield is 1.5X covered by DCF.

Overall earnings confirmed the predictability of cashflows in the midstream sector. It is often described as a “toll-like” business model. The pandemic-induced collapse in 2020 challenged this description, but performance since then has shown that the description remains apt. Attractive dividends with ample coverage from DCF is common across the sector.

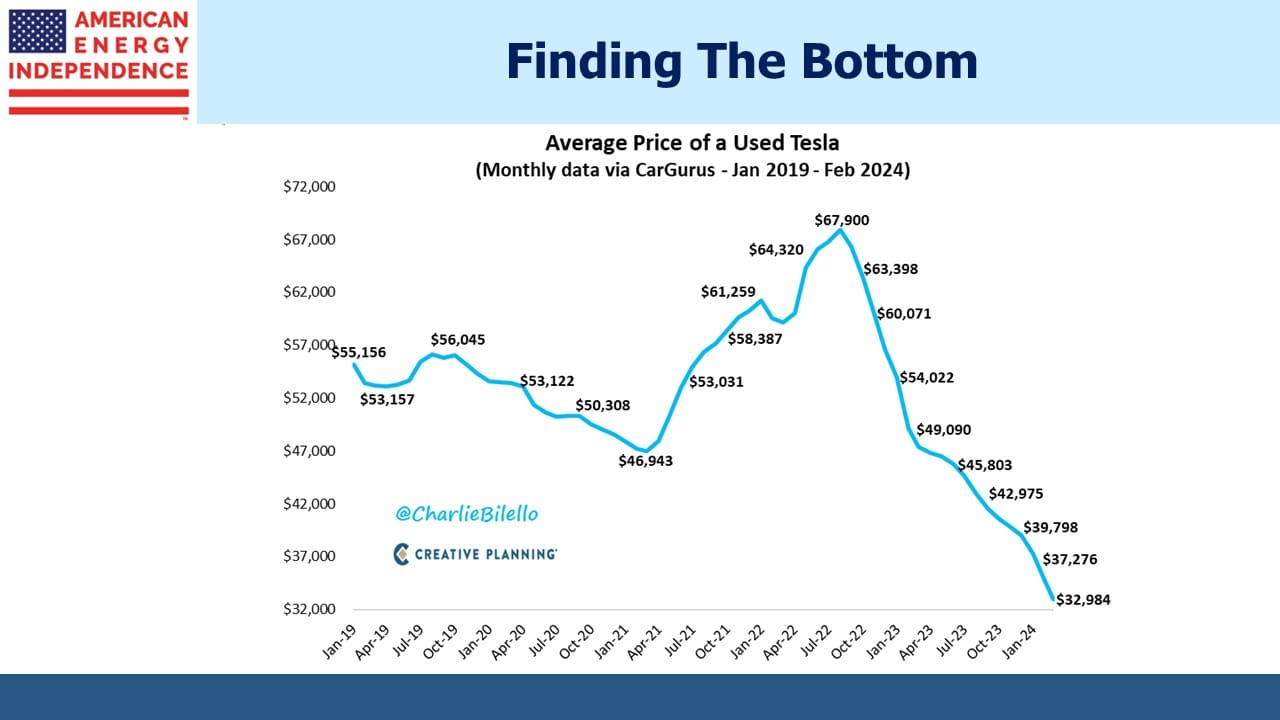

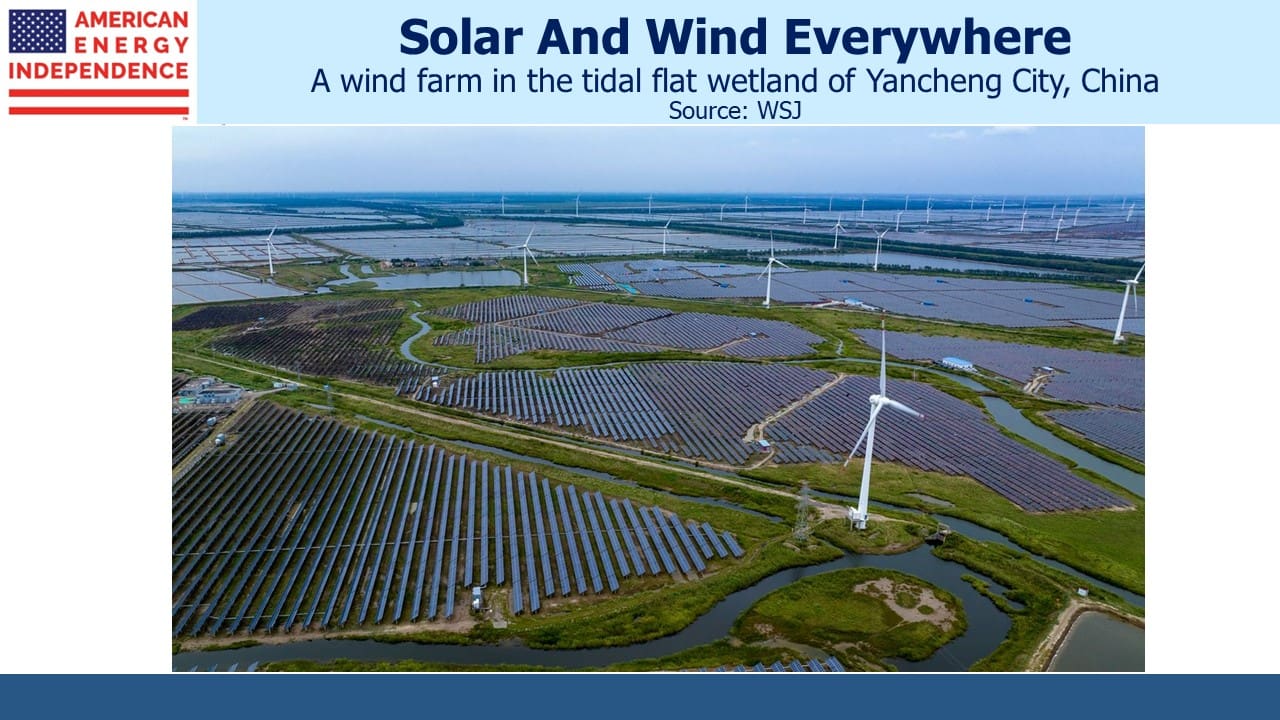

I was struck by a chart the other day showing a sharp drop in the price of used Teslas. A couple of years ago wait times of as much as a year were common for buyers to take delivery of their new vehicle. Nowadays it’s a few weeks, and sales have slowed so that Electric Vehicles (EVs) are taking dealers longer to shift than conventional cars.

The halving of resale values for EVs reflects consumer realization that they’re nice to drive but charging is inconvenient. Cold weather reduces their battery range, as does age. As suggested in this video (see Stop Paying For Overpriced EVs), these are the reasons they ought to be cheaper than an equivalent gas-powered car. Reduced resale value boosts annual depreciation, increasing the cost of ownership.

EVs are gradually finding a more appropriate price point.

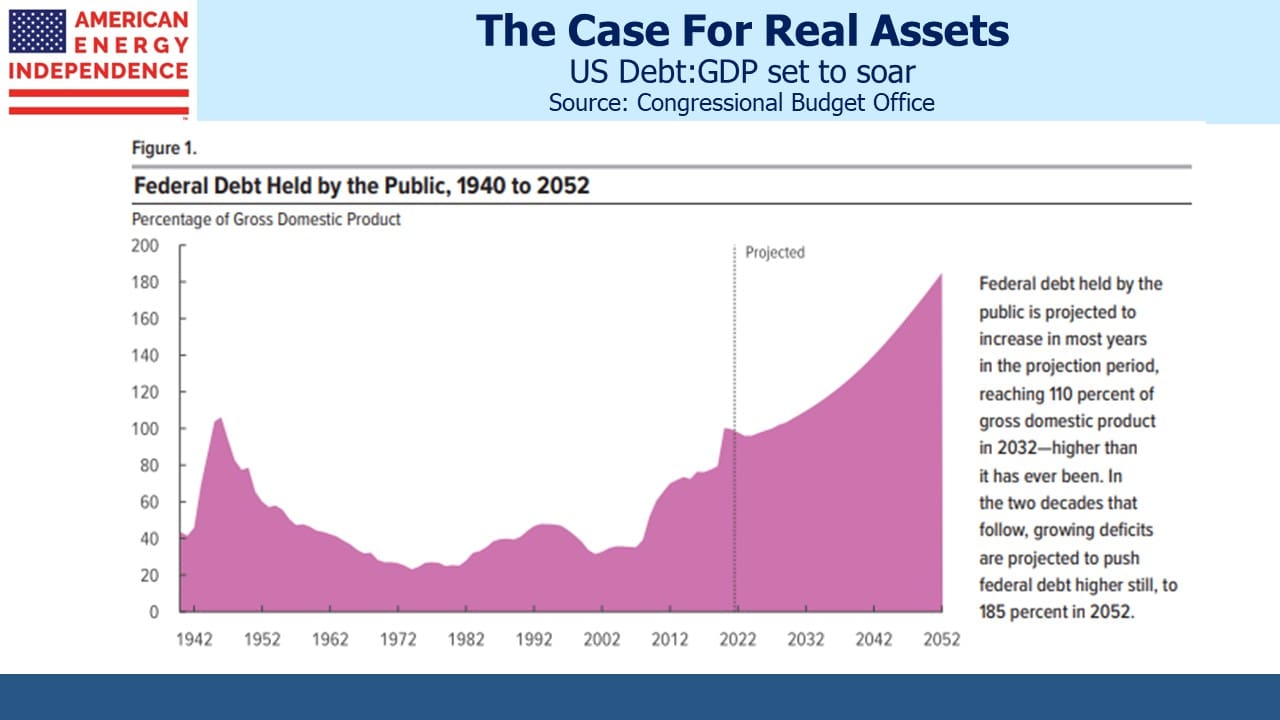

We have three have funds that seek to profit from this environment:

Energy Mutual Fund Energy ETF Real Assets Fund