Bond Buyers And Tariffs

Although the US is energy independent and a net exporter of petroleum products, we still import certain blends of crude. Canadian tar sands oil is the heavy type for which American refineries are configured as is Mexican oil. Shale oil is lighter. So we buy what we are set up to handle and sell what we’re not. This is just one example of the complex set of trade ties that bind the North American continent together.

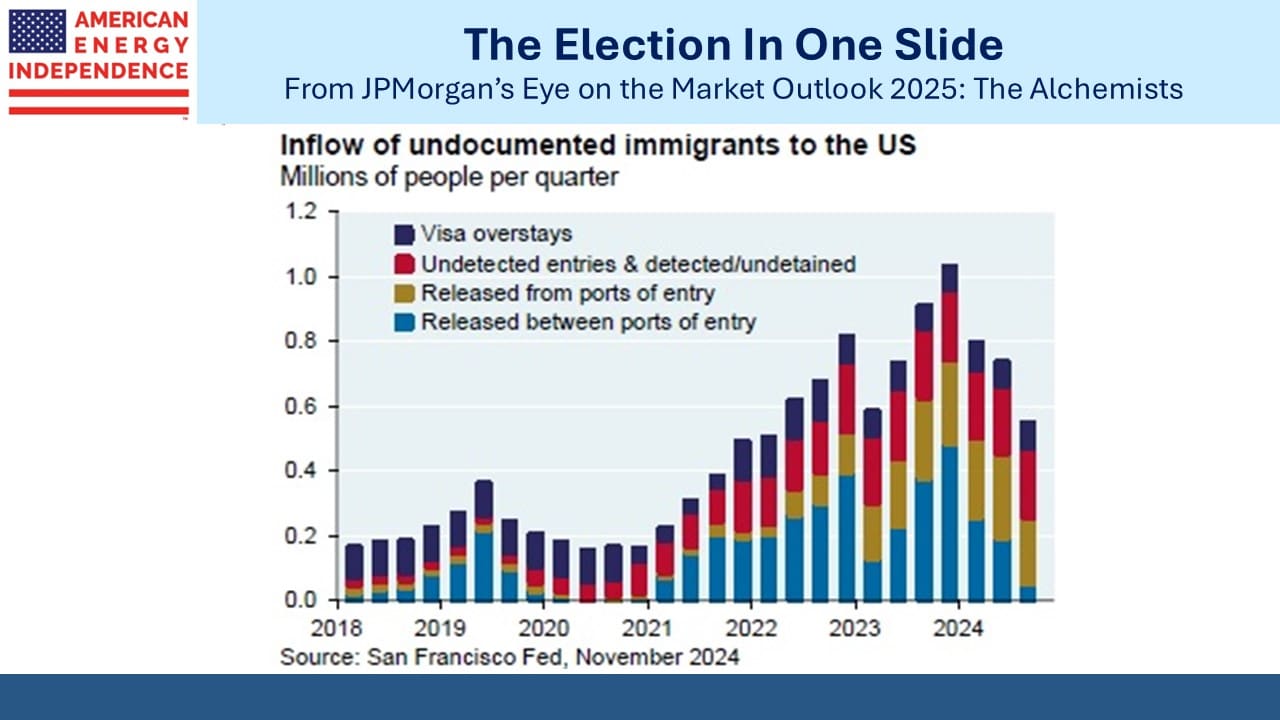

There’s unlikely to be any economic benefit from tariffs, which can also correctly be termed import taxes. They can further non-economic goals, such as Mexico’s agreement to station 10,000 troops on our border to prevent illegal immigration. Opinions vary as to whether they’re inflationary, although most analysts agree that they’re a net negative on GDP growth. Much depends on whether retaliation leads to a ratcheting up and extended period of trade friction.

Based on the rhetoric leading up to Saturday’s announcement, they’ll be more impactful on Canada and Mexico than the US. Both countries’ currencies initially weakened vs the US$. Theoretically our trading partners could fully absorb the cost of the tariffs. In practice, as with sales taxes, it will be split between producers and consumers.

Goldman Sachs estimates that the 10% import tax (ie tariff) on Canadian crude will be 2/3rds absorbed by Canadian producers and 1/3rd by US refineries which will presumably pass this on to consumers via price hikes for gasoline and other refined products. Last year we imported 3.8 Million Barrels per Day (MMB/D) of crude and 0.3 MMB/D of refined products from our northern neighbor. Mexico provides just under 0.5 MMB/D of oil.

Canada has long struggled to get its crude oil from Alberta to export markets. They don’t have any good alternatives to shipping to the US for now. The Keystone Pipeline which runs south to the Gulf of America (Chevron recently adopted this new name) runs at close to 100% capacity. It’s why TC Energy tried for years to build the Keystone XL, which Biden ultimately quashed when he took office in 2021.

The Transmountain pipeline runs west to British Columbia. Its expansion project was completed in 2024 at substantial increased expense and after long delays by the Canadian federal government who bought it from Kinder Morgan in 2018 (see A Closer Look At Canada’s Newest Pipeline). This also operates at close to full capacity. Crude oil can move by rail, but that’s substantially more expensive and not as safe. In 2013 a train carrying crude exploded in Quebec, killing 47 people (see Canada’s Failing Energy Strategy).

Canada’s crude oil options are limited.

The Administration’s goals with tariffs aren’t completely clear. Canada’s not a big source of illegal immigration or fentanyl, and there’s zero chance Canadians want to be the 51st state. Trump has claimed that we subsidize Canada in the form of our deficit with them, but that’s not the right way to think about the purchase of goods in a free market.

If the US is pursuing a narrower trade deficit, a consequence not so far considered publicly is its impact on our fiscal deficit. Over the past twelve months our trade deficit is $879BN. Those US$ that foreigners accumulate have to be invested back in the US, and a significant portion wind up in treasury securities. Canada owns $374BN. Japan owns $1.1TN and China $769BN. If our trade deficit shrinks, foreign countries will have fewer US$ to invest back in the US.

Absent a lower fiscal deficit, US savers will need to provide more of the financing which will require higher bond yields. Today’s interest rates are inadequate to induce sufficient domestic saving. Coupled with this is that an extended period of trade conflict intended to reduce our trade deficit will probably cause some countries to deem US bonds less attractive anyway for political reasons. China has been lowering its US holdings in recent years as trade tensions have risen.

There’s little reason to expect any improvement in the fiscal outlook. Elon Musk’s Department of Government Efficiency will hopefully uncover some savings, but nothing is likely to change about the trajectory without policy changes. Strong GDP growth is our best near term option.

A weaker economy due to trade friction might lower bond yields. Tariffs might be inflationary. But we’ll need people to buy our bonds, and if there are fewer foreign buyers we’ll need to own more here, which will require lower consumption and more saving by US households.

In an unintended consequence, it may turn out that running a trade deficit keeps interest rates lower than they would be otherwise. We may be on track to find out.

We have two have funds that seek to profit from this environment:

Energy Mutual Fund Energy ETF