Midstream Dances To A Different Tune

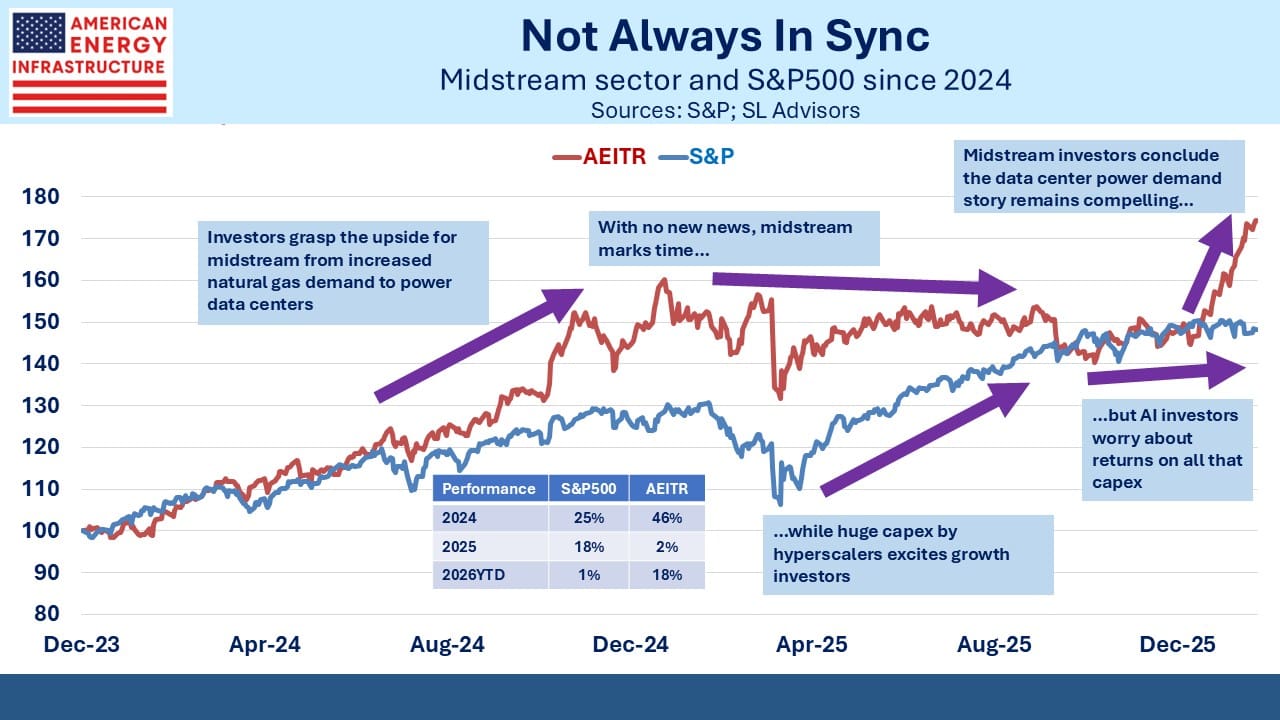

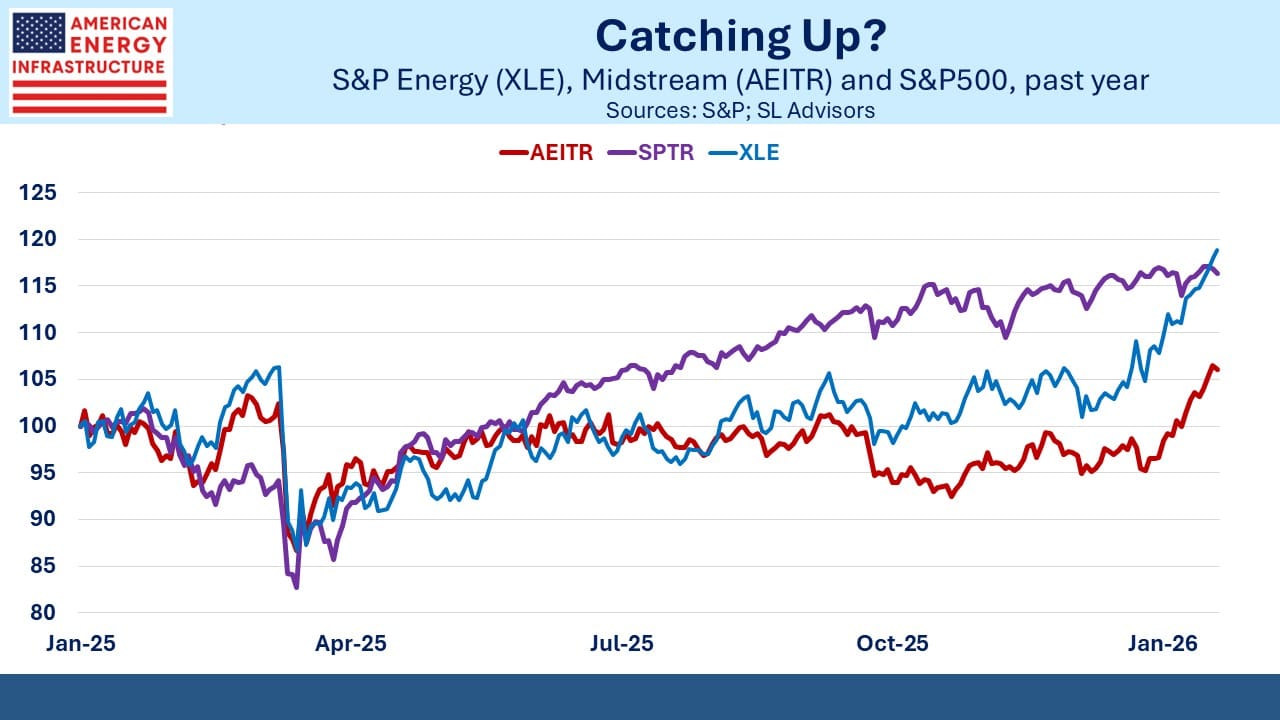

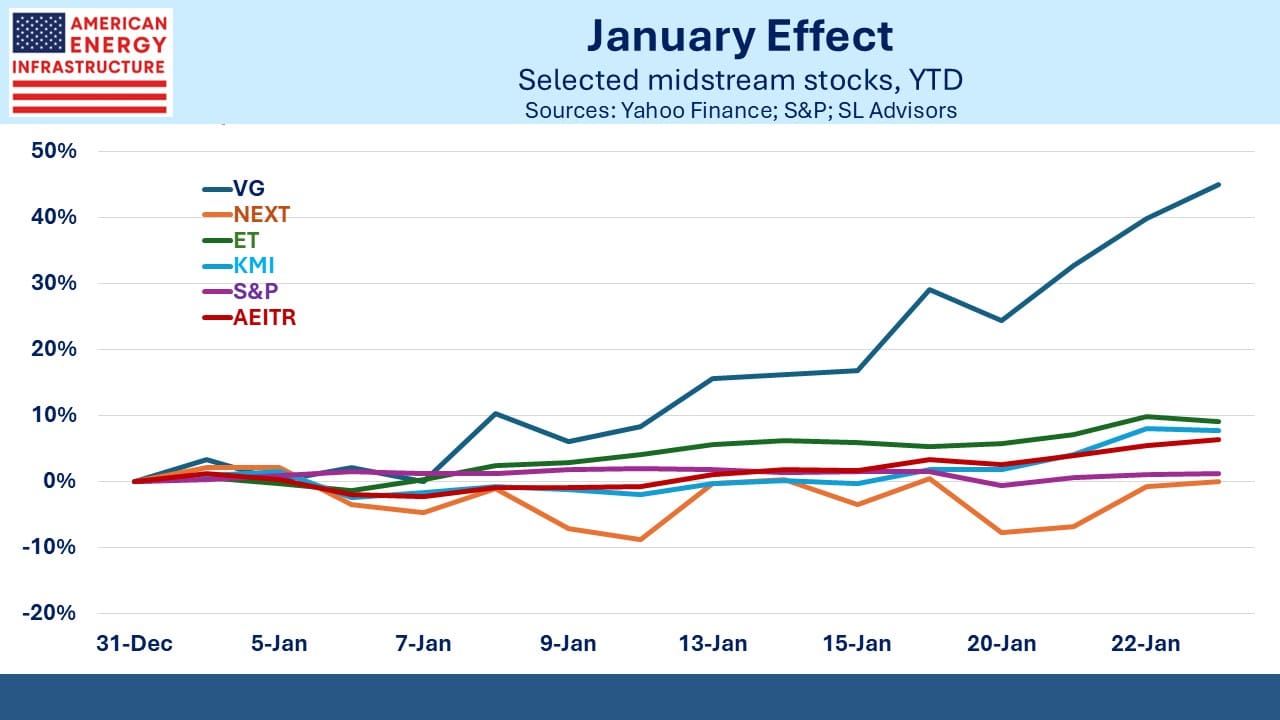

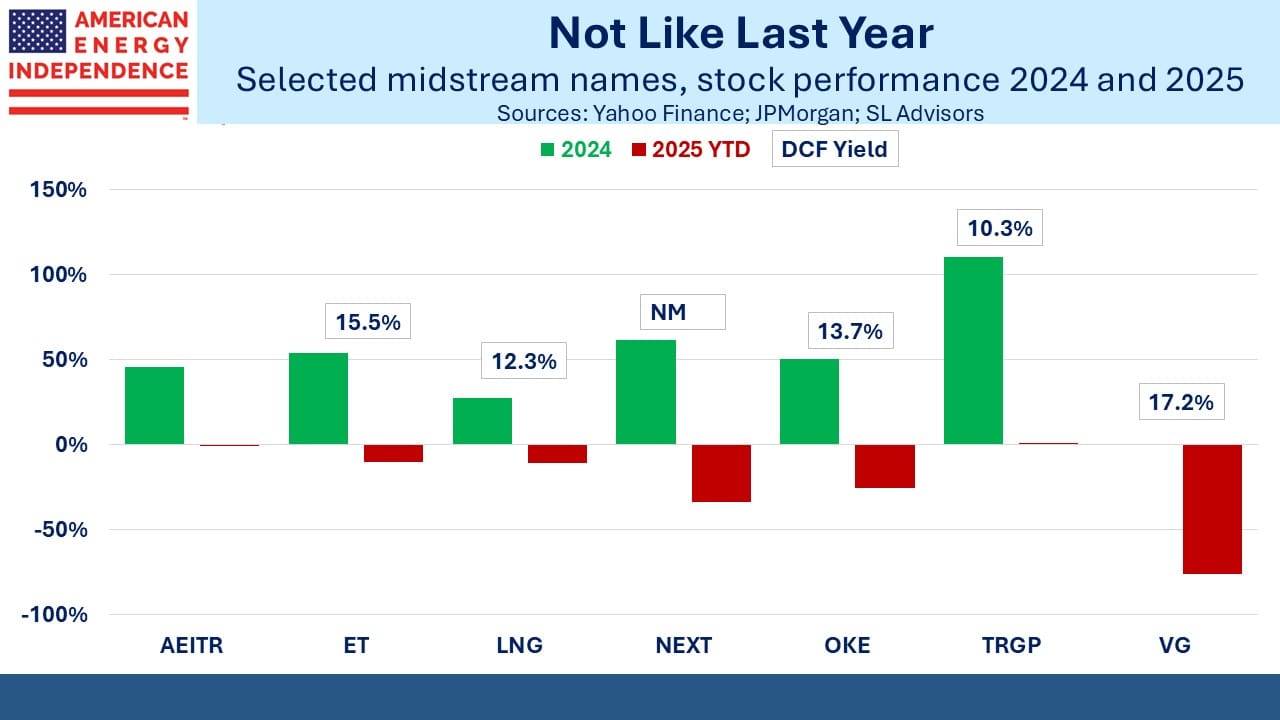

The performance of midstream last year didn’t align with the fundamentals. This is clear when you consider the periods either side (2024 and 2026YTD). Last year, the sector lagged and many investors became frustrated with the underperformance versus the S&P500, which really means versus the big AI hyperscalers.

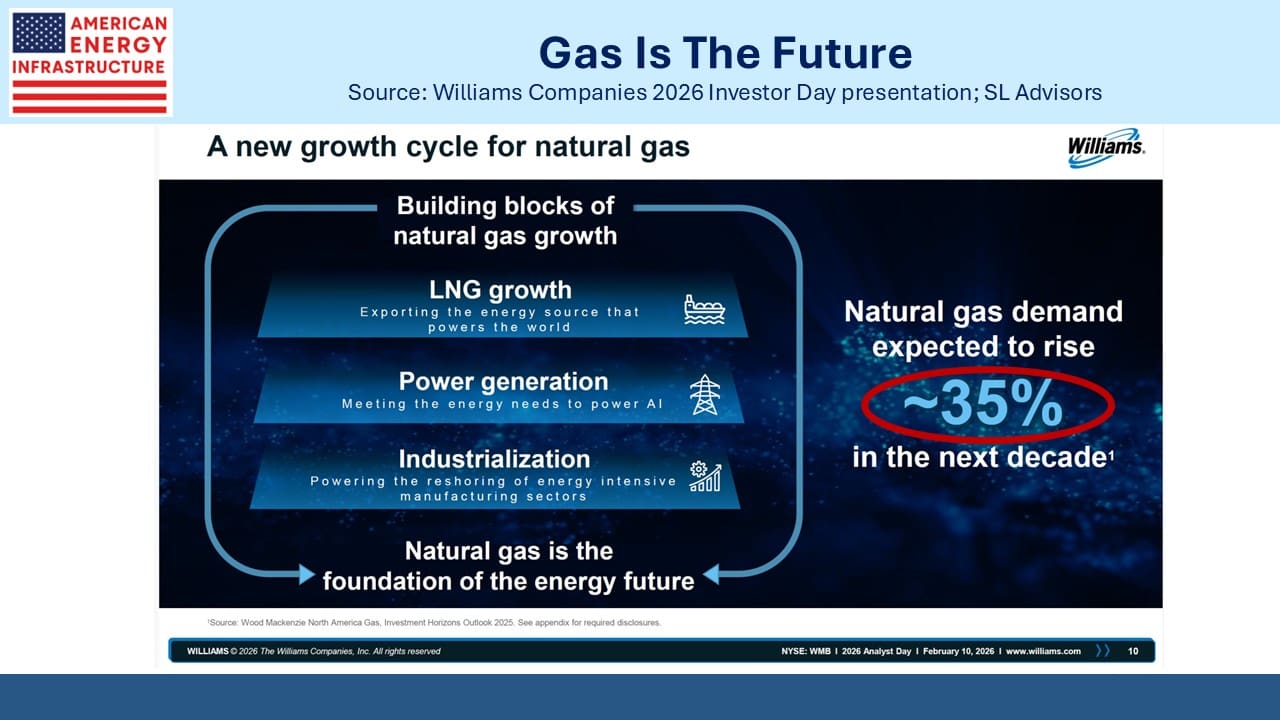

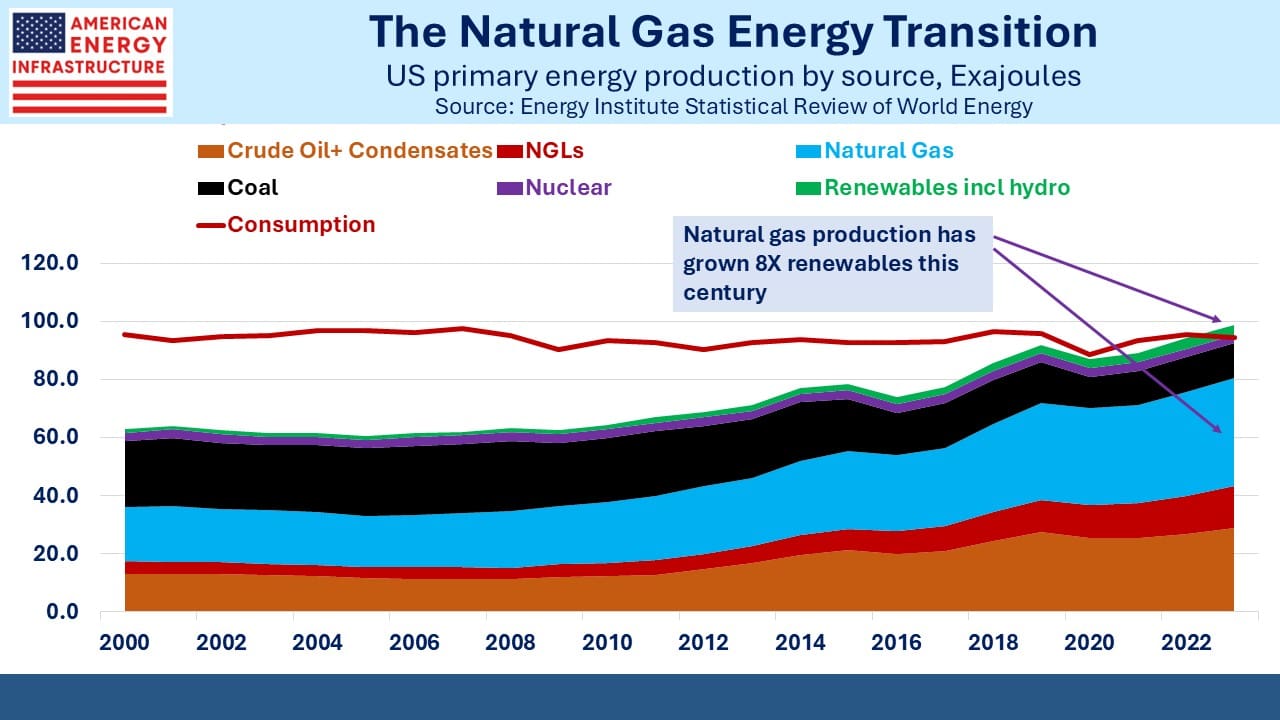

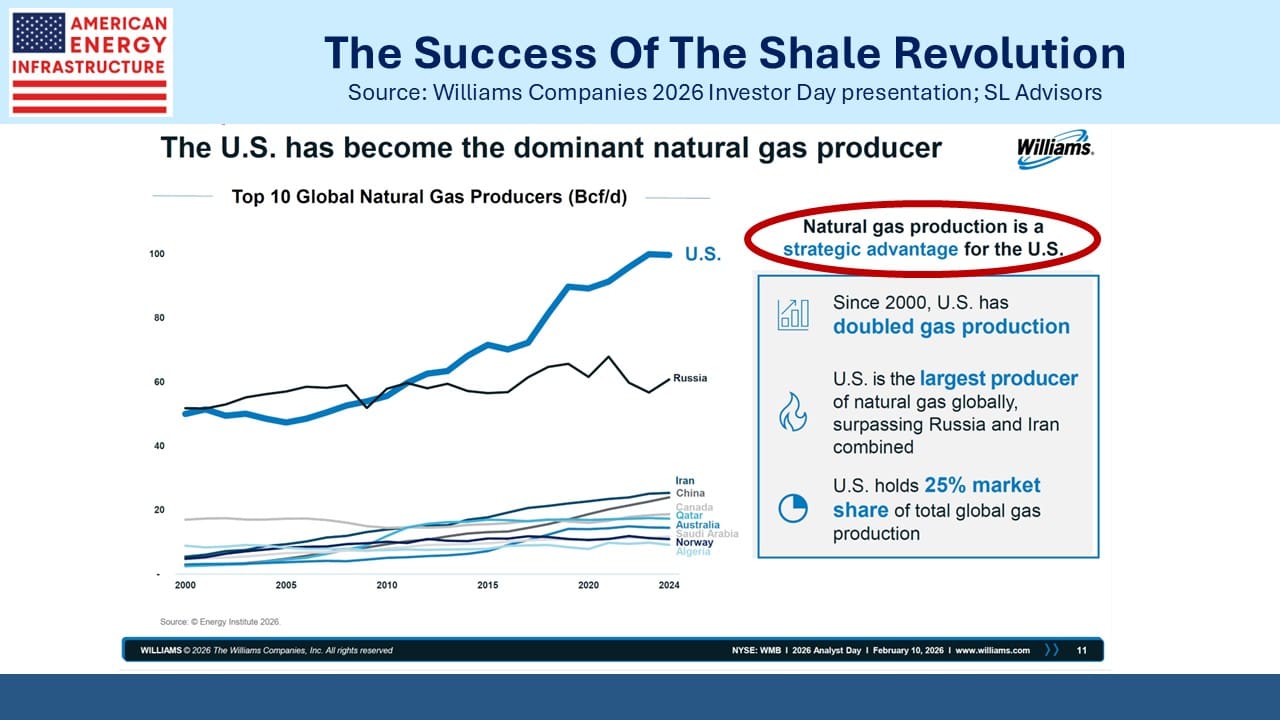

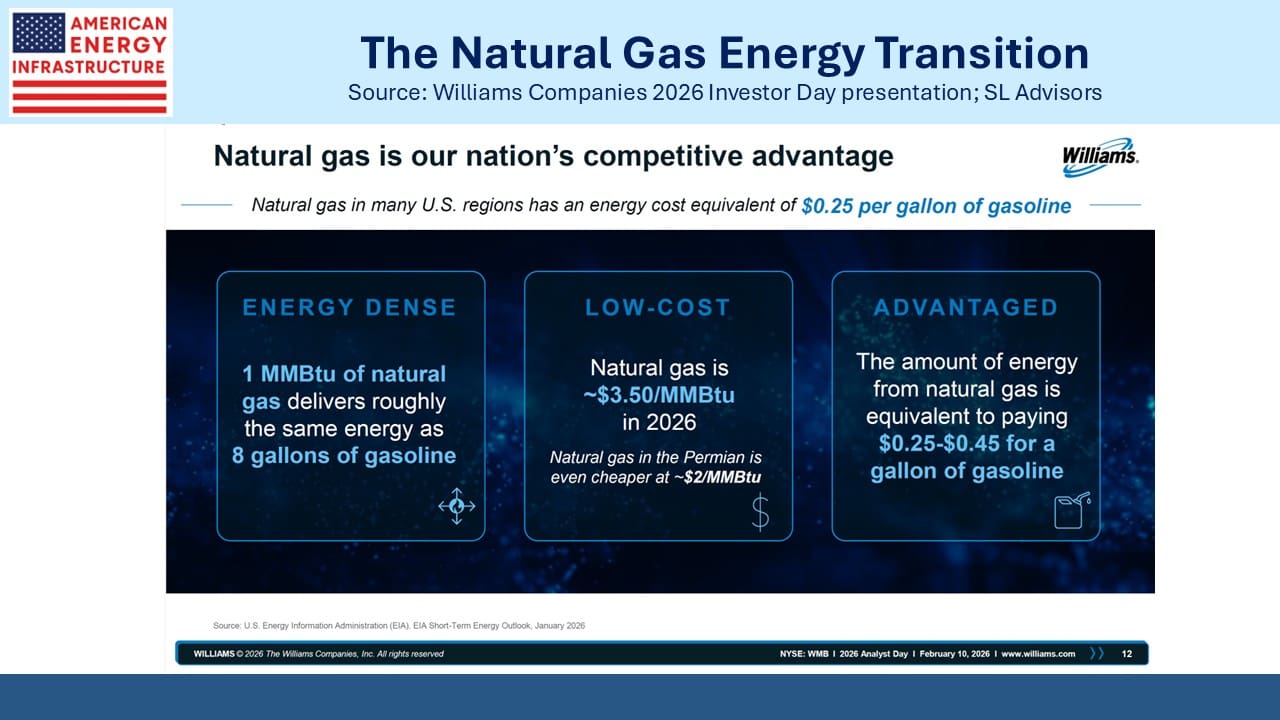

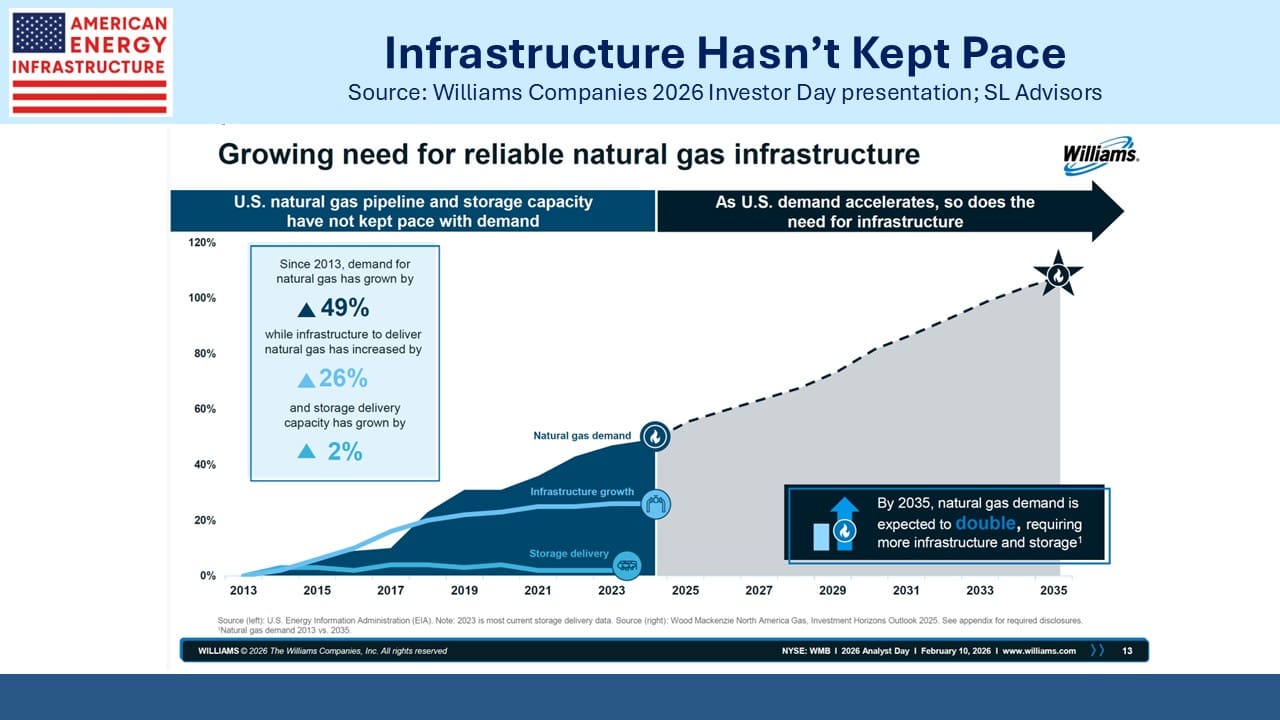

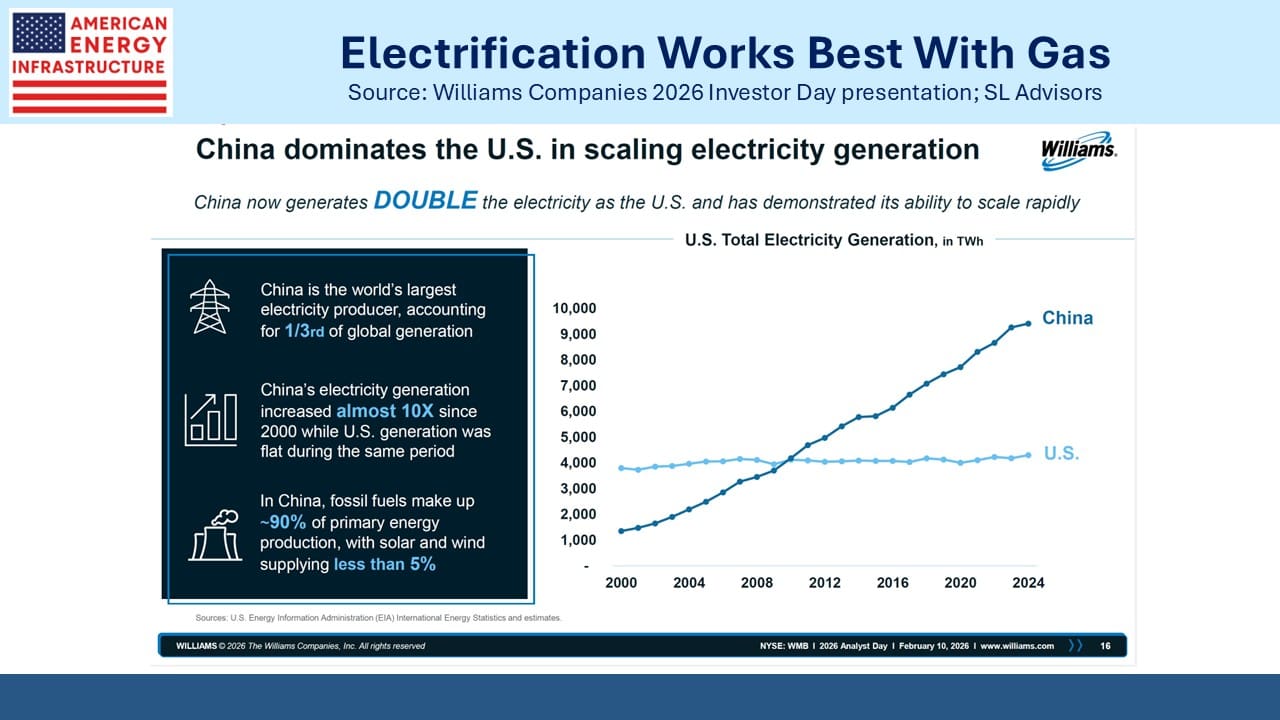

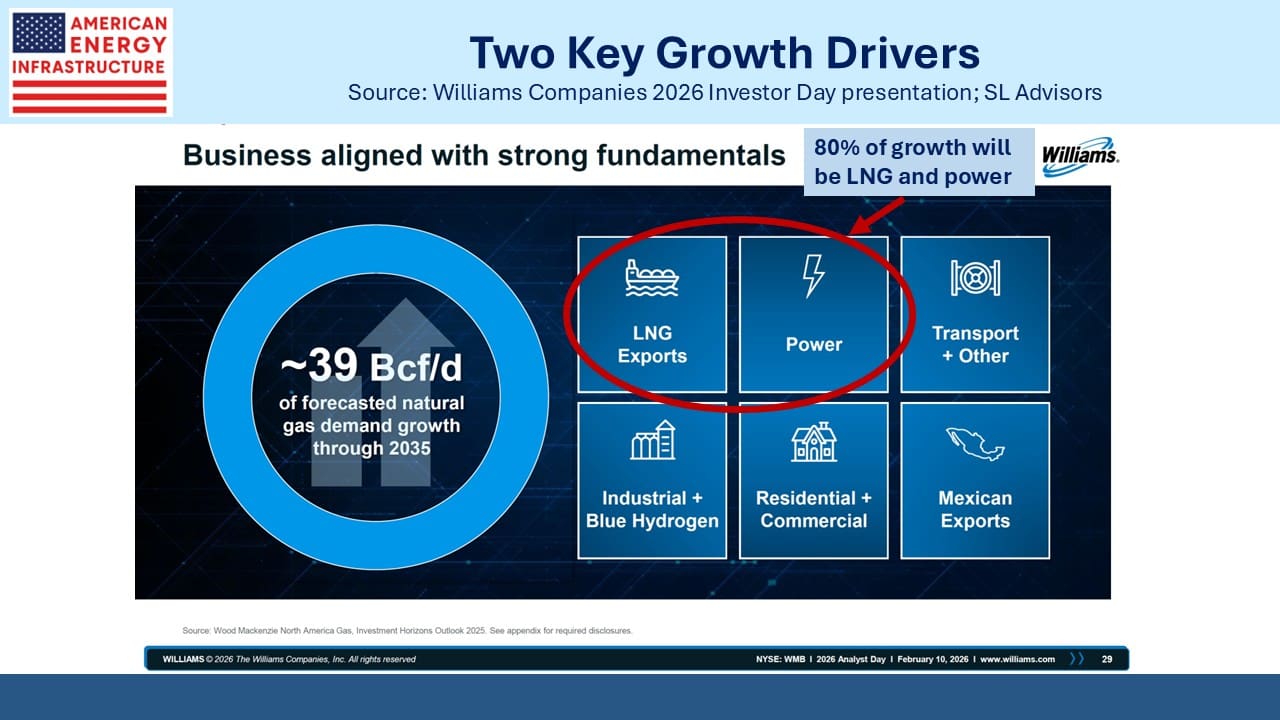

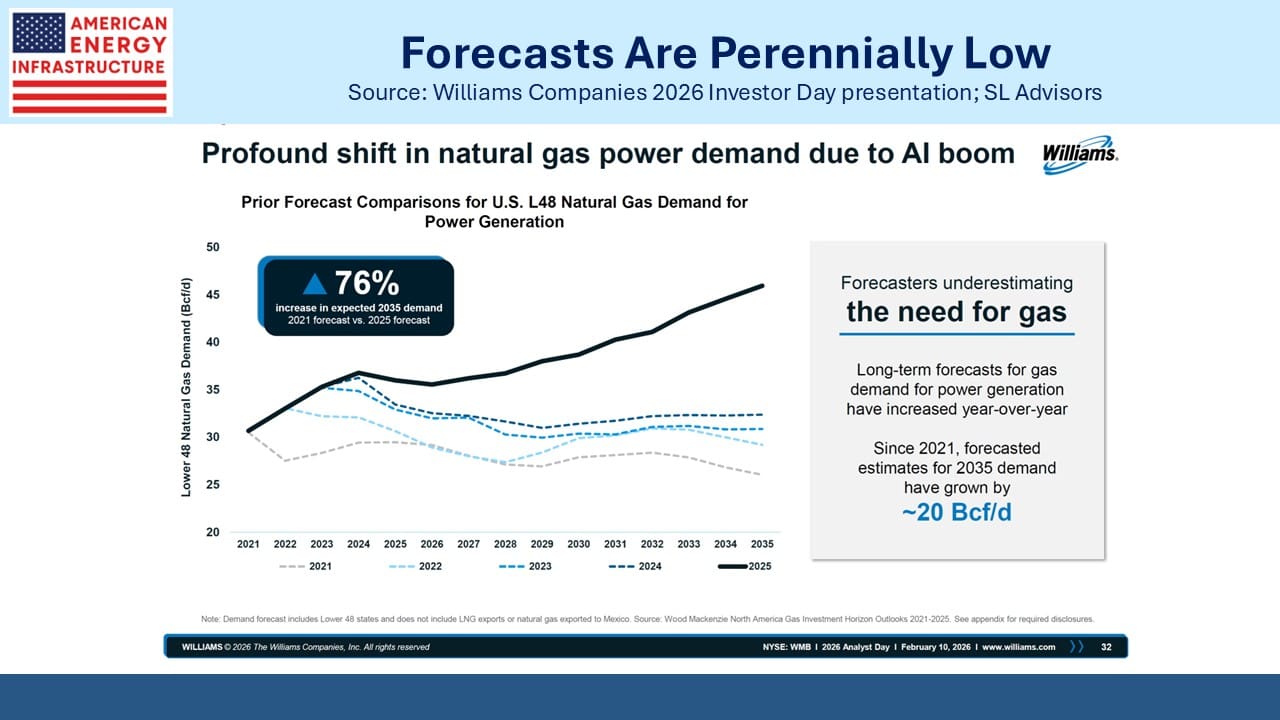

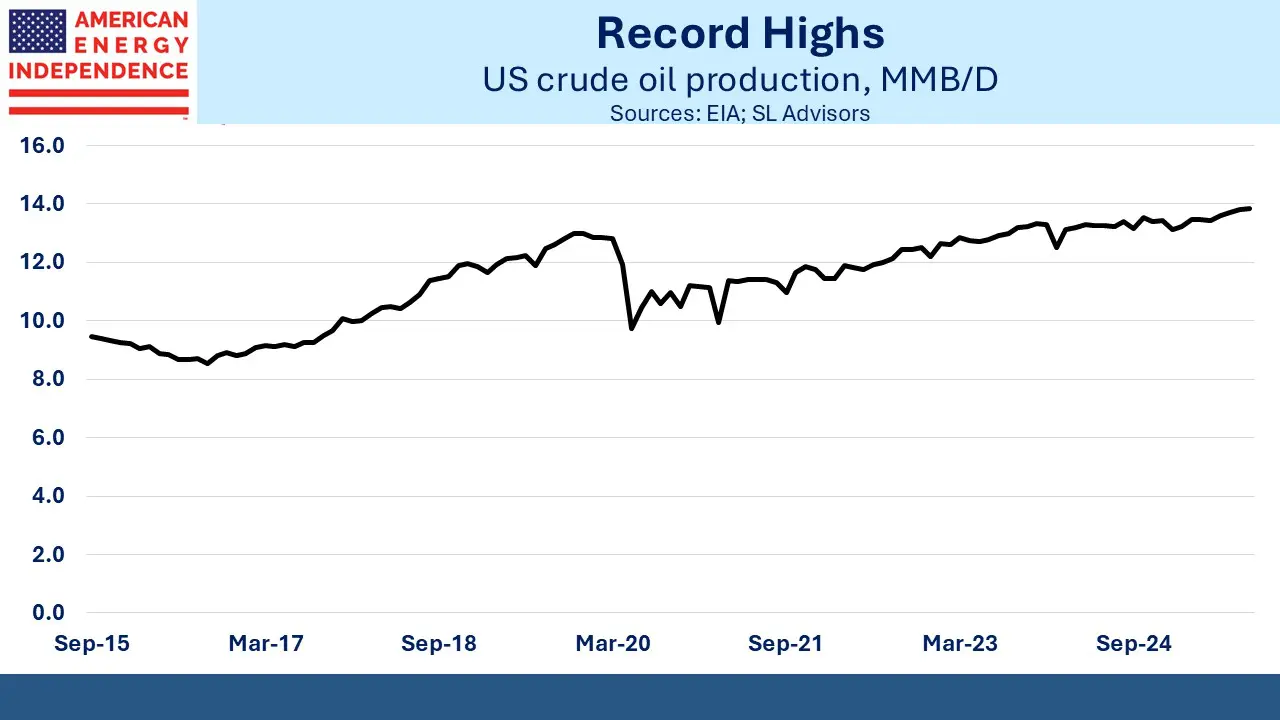

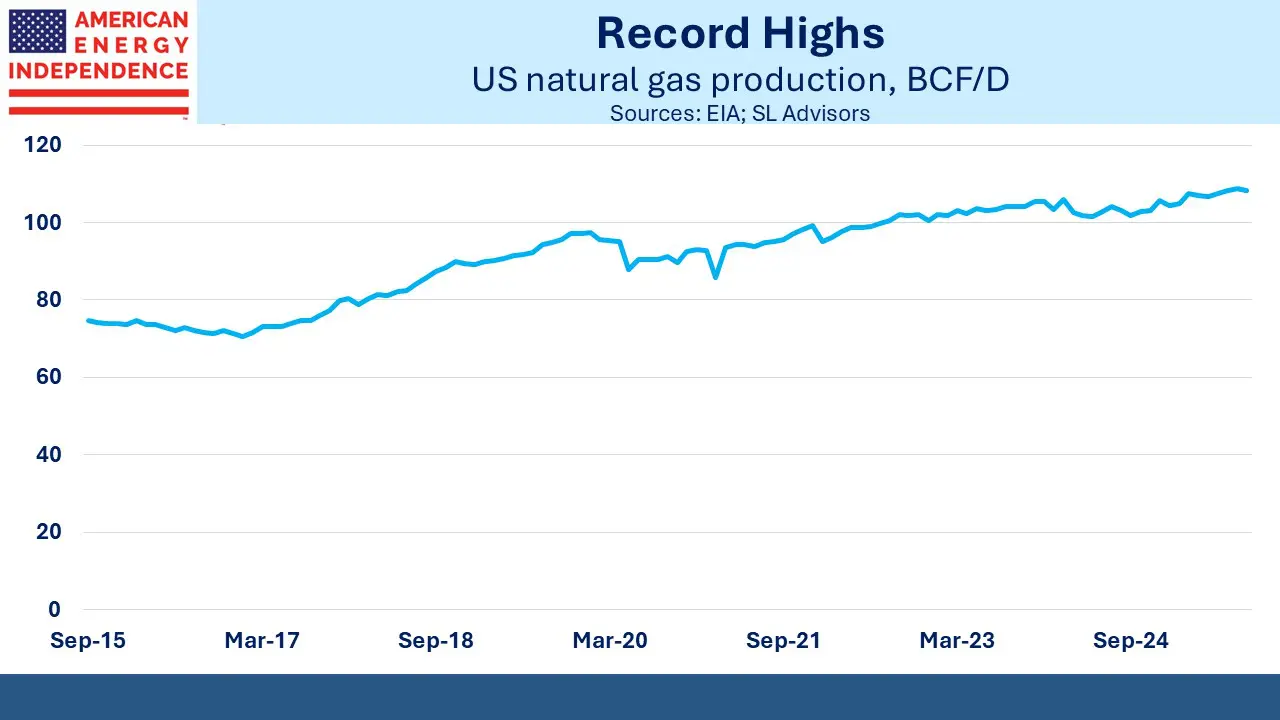

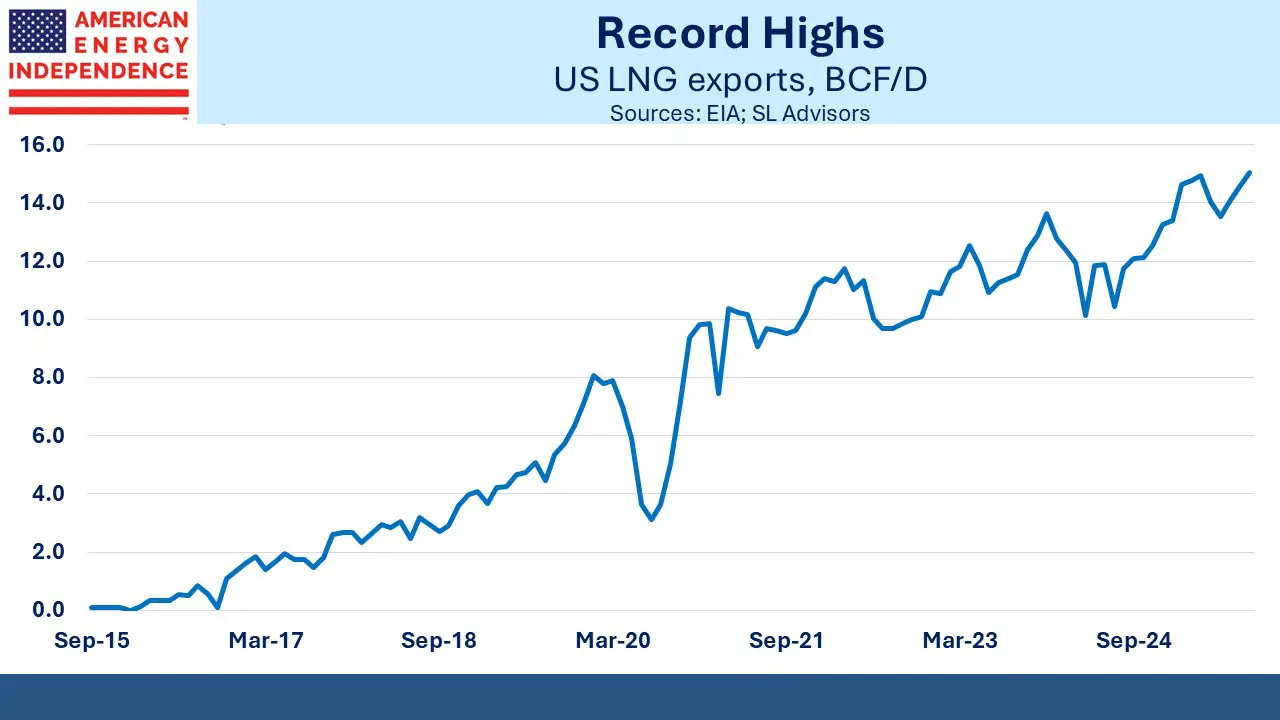

In 2024 midstream investors grasped the need of data centers for more power, and how this would inevitably lead to increased natural gas demand since it’s cheap, reliable and abundant in the US.

Companies such as Williams (WMB) developed Behind The Meter (BTM) solutions under which a dedicated gas supply feeds a power plant that provides electricity to the data center. This avoids connecting through the grid and potentially driving up prices for all consumers, an issue that’s drawn much unwelcome attention recently.

Oddly, this positive sentiment didn’t persist into 2025 in spite of the AI story leading the overall market higher. Data centers still needed power and the role of gas-oriented midstream companies such as Energy Transfer (ET) and Kinder Morgan (KMI) in providing BTM solutions.

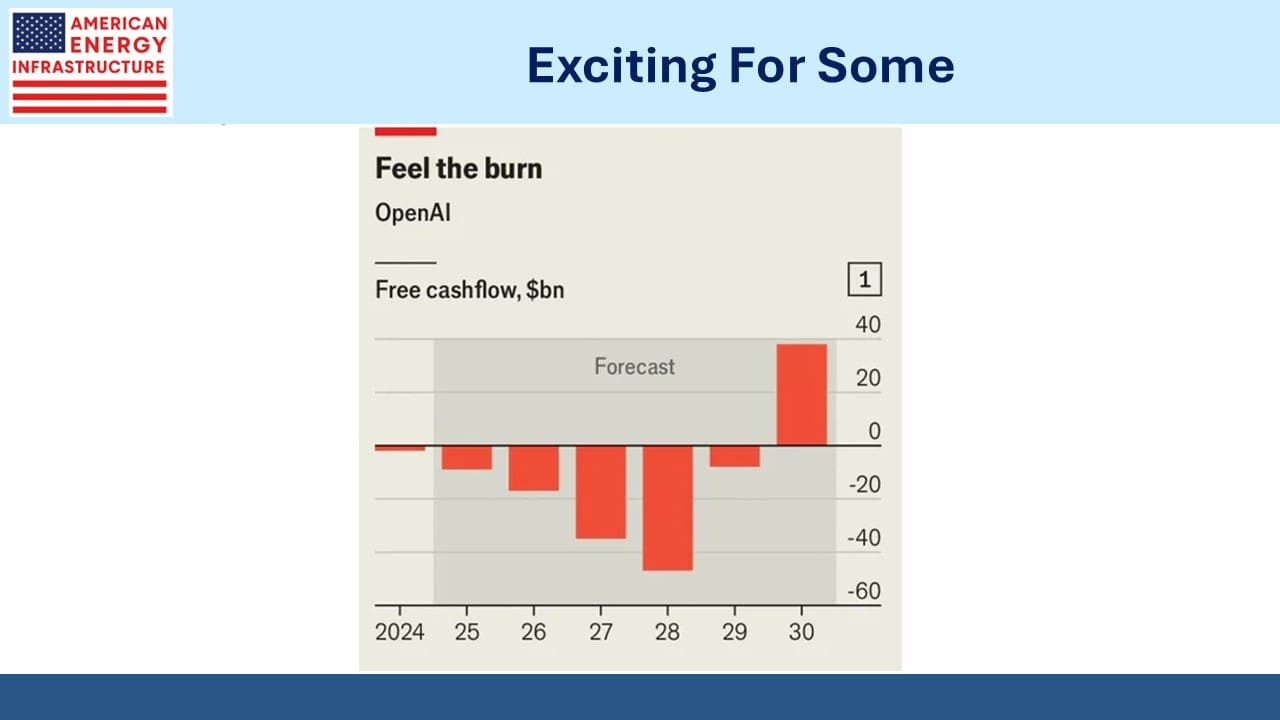

Not that many years ago, the big IT firms were sitting on enormous cash piles and faced pressure from investors to deploy or return it. The AI revolution has at least provided a use for some of that cash.

This year’s concerns about spending have caused sector rotation from growth to value. Midstream, along with energy stocks more broadly, has benefited. Over the past year or so, midstream performance has been driven by sentiment shifts leading to sector rotation more than changing fundamentals for the pipeline sector itself.

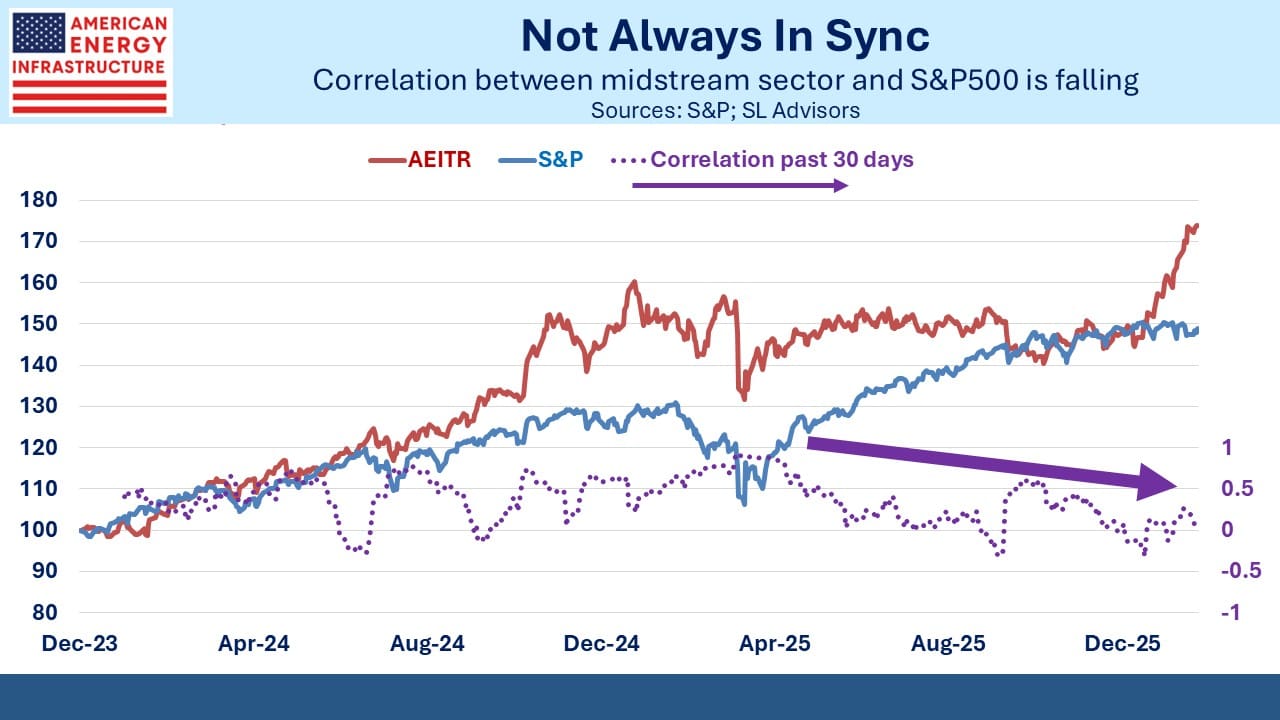

The result is that the correlation between the American Energy Infrastructure Index, representing the midstream sector, and the S&P500 has been falling over the past year, defined here using daily returns over the prior month. This year at times it’s been negative, and it’s fair to say that midstream and the stock market have no meaningful correlation.

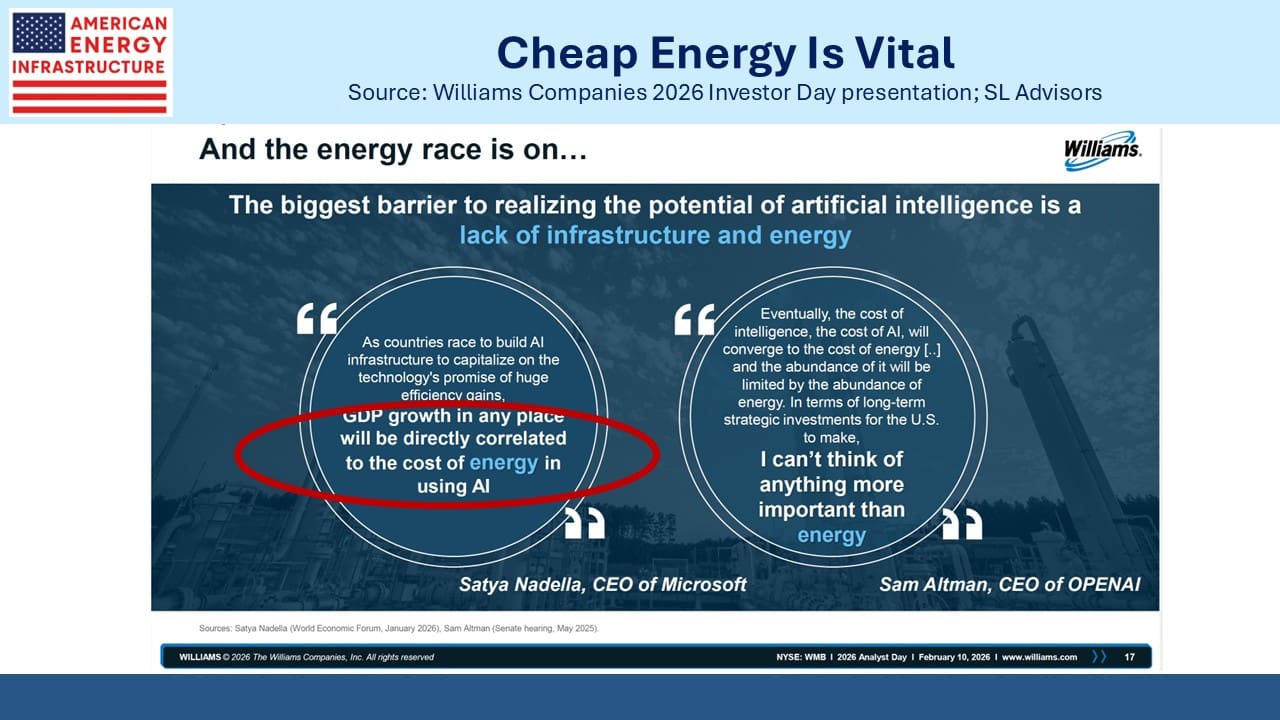

Fundamentally, it shows that the concern about returns on AI-related capex doesn’t extend to the companies who will provide the natural gas infrastructure to power centers. Hyperscalers are expected to spend $450BN on AI capex this year. But BTM deals will typically require long term contracts that ensure an adequate return on the infrastructure, similar to the take-or-pay contracts commonly used for pipeline capacity.

It means midstream can act as a useful diversifier in a portfolio. The underlying fundamentals are strong, but in addition it’s not that exposed to the shifting sentiment among growth stock investors.

The low correlation with the market is less useful when overall returns are strong. But the tide is shifting as concerns grow about the scale of the hyperscalers’ capex plans.

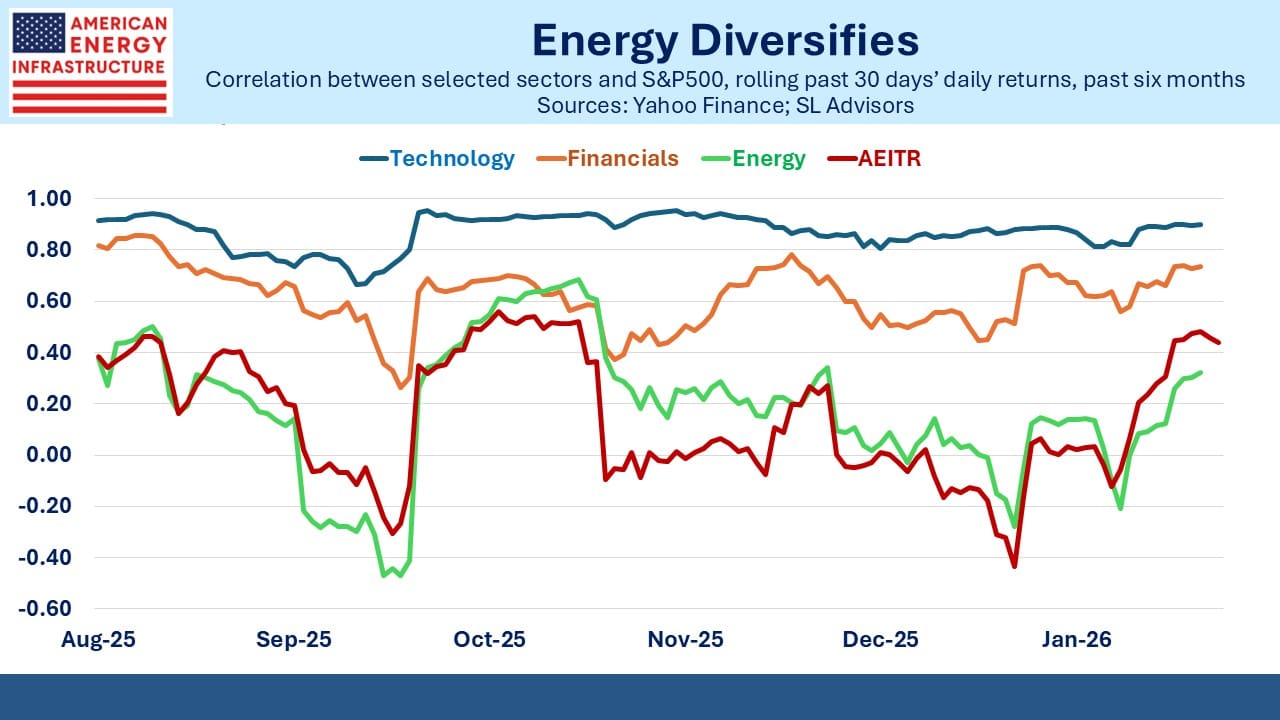

Technology has been highly correlated with the S&P500, at above 0.8 for the past several months and often above 0.9. Energy along with the pipeline sector has generally not been correlated. This frustrated investors when tech stocks were hot, but it’s now turning out to be a more valuable feature.

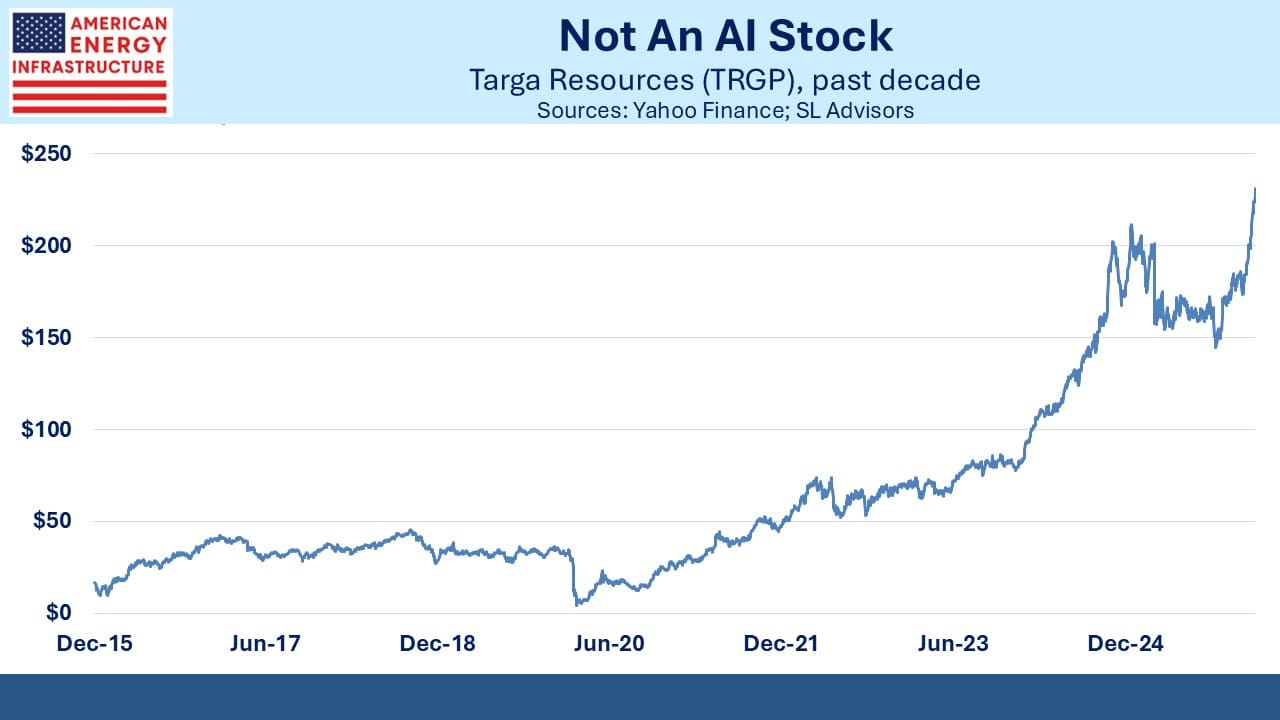

For long term performance, the Targa Resources (TRGP) chart is quite a sight. My partner Henry and I have often debated the merits of this position. In late 2020 I flippantly called TRGP a “perennial misallocator of capital” (see Pipeline Buybacks and ESG Flexibility) as they initiated a buyback program with the stock price at $15 (Friday’s close was $231).

Former CEO Joe Bob Perkins frustrated many investors when he dismissed critics of their capex plans, saying their opportunities were really “capital blessings.”

Fortunately for our clients, Henry’s articulate defense of retaining our TRGP position was invariably convincing.

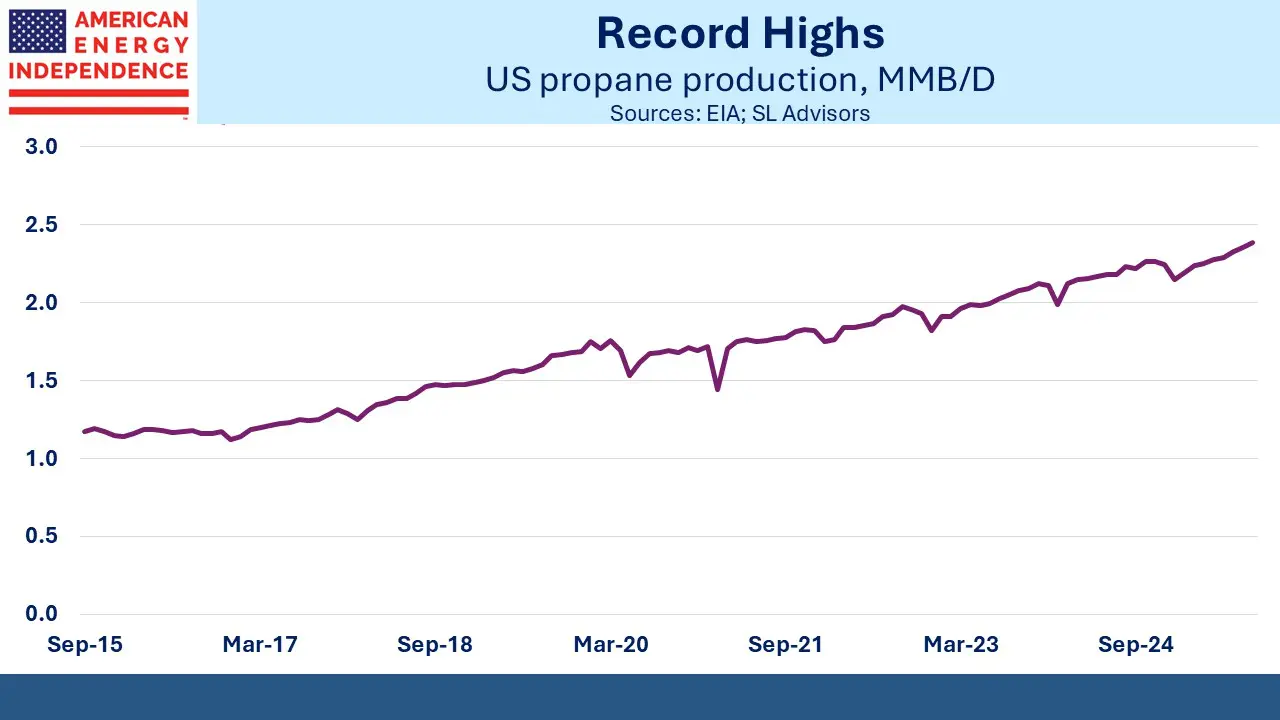

At the worst of the pandemic, TRGP lost 86% of its value from its previous high two years earlier. It subsequently rebounded to 38X that level. TRGP has developed a vertically integrated business in the Permian basin focused on natural gas and natural gas liquids (i.e. ethane and propane).

In early 2023 they acquired the remaining 25% of the Grand Prix NGL pipeline in Texas that they didn’t already own from Blackstone. Full ownership allowed them to improve their margins. Their stock is up 3.5X since then. Their quarterly dividend has grown from $0.35 to $1, although given the stock performance this still leaves it with paltry 1.8% yield.

But in recent years they’ve been buying back stock in similar amounts to their dividend payout. Last year they spent $755MM and the prior year $642MM. Distributable cash flow growth is solidly in the teens.

TRGP is quite a story.

Last week we had the opportunity to catch up with long-time friend and investor Dave Pasi and his charming wife Diane. At the risk of upsetting our friends up north, al fresco dining is thriving in Naples, FL. Dave was pushing his clients to add to their midstream positions last year, advice that looks especially good right now.

We have two have funds that seek to profit from this environment:

Energy Mutual Fund Energy ETF