Life Gets Complicated For The Fed

Making eurodollar futures interesting is not among Fed chair Jay Powell’s goals, but he’s achieved it nonetheless. From just after their June FOMC meeting through Thursday, the market has lopped over 0.50% off the projected rate cycle. The cycle peak has even been brought forward, from March 2023 to this coming December. The FOMC’s Statement of Economic Projections (SEP) has rates peaking at the end of next year, a forecast Powell described as “probably the best estimate of where the Committee’s thinking is still.”

Thursday’s GDP report showing a second consecutive quarter of GDP contraction further complicates matters. With the economy probably operating at beyond full employment, we’re hardly in a recession although signs of slowdown are there to see. The most important factor that will determine this rate cycle peak is the FOMC’s inflation/unemployment trade-off. The inflation figures should start improving, because old data will recede beyond twelve months, which will improve year-on-year measures of CPI.

JPMorgan’s Michael Kelly believes the Fed should be extremely patient in seeing inflation drop, suggesting that a pace of 1-2% annual reductions over several years should suffice. Conversely, the credibility argument suggests that a faster pace of falling inflation is critical to maintain expectations anchored at 2%. The rate cycle implied by these contrasting views is very different.

The range of outcomes is unusually wide. Rapid yield curve adjustments reflect heightened interest rate volatility and uncertainty. Behavioral finance teaches that overconfidence is a common mistake. Bond traders with humility are likely to be the most successful.

The current inversion in the eurodollar futures curve, mirrored in the spread between two and ten year treasuries, offers an asymmetric risk/return to this market observer. We’re already priced for substantial risk of recession. A soft payroll number or benign inflation release will quickly push the yield curve towards a more positive shape. Even by the value-less standards of today’s bond market, ten year treasury yields at 2.7% offer nothing to the discerning investor.

The Fed’s ponderous rate of balance sheet normalization omits auctioning off some of the mortgage-backed securities (MBS) they acquired through last year. When the Federal government can borrow at 6% below current inflation, that is both highly stimulative and reflective of sharply slower GDP growth. Forecasting interest rates is exceptionally hard right now.

Advice to the Fed is plentiful and not nearly as useful as figuring out what they will do. In time they may conclude that long term rates need to rise to achieve their objective. Policy remains highly stimulative, and short term rates matter less than bond yields. Auctioning MBS would slow growth more effectively. Quantitative Tightening as practised by the Fed, allowing bond holdings to passively run off, is not the analog to the active buying of bonds that was Quantitative Easing. Barry Knapp of Ironsides Macroeconomics correctly noted that Powell should have received questions on this topic during Wednesday’s press conference.

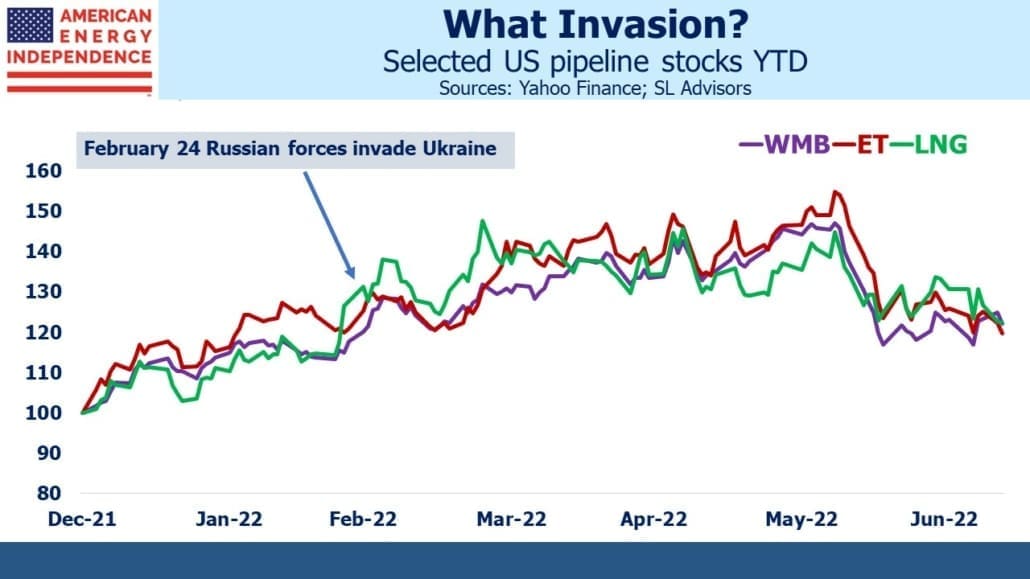

Switching to pipelines, the American Energy Independence Index (AEITR) briefly touched its pre-Ukraine level for last week. Pipeline earnings so far have been good. Although recession fears caused the sector to pull back earlier in the month, we expect to see continued evidence of strong fundamentals as other companies provide updates. The AEITR is +27% over the past year, compared with the S&P500 which is down 6%.

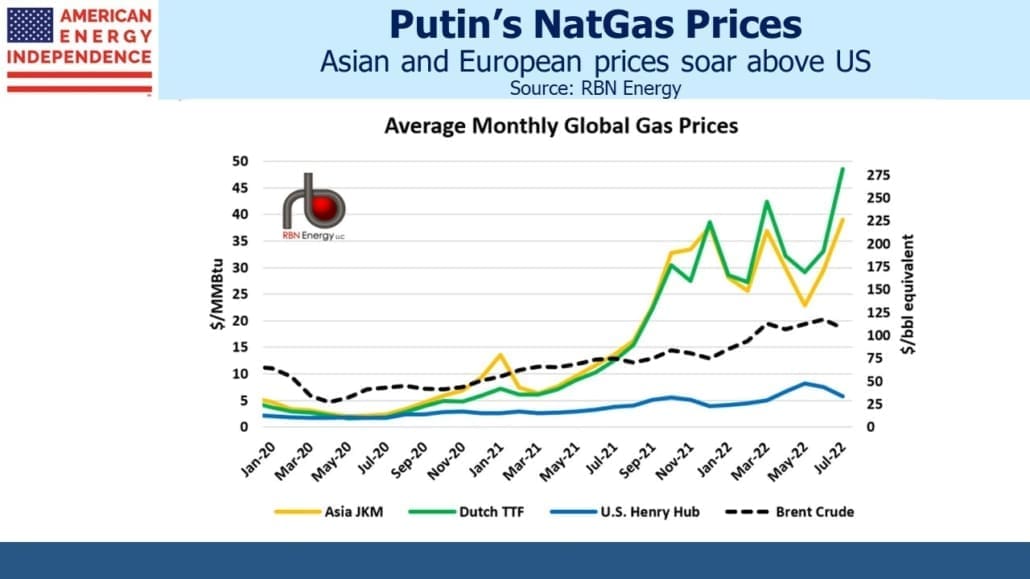

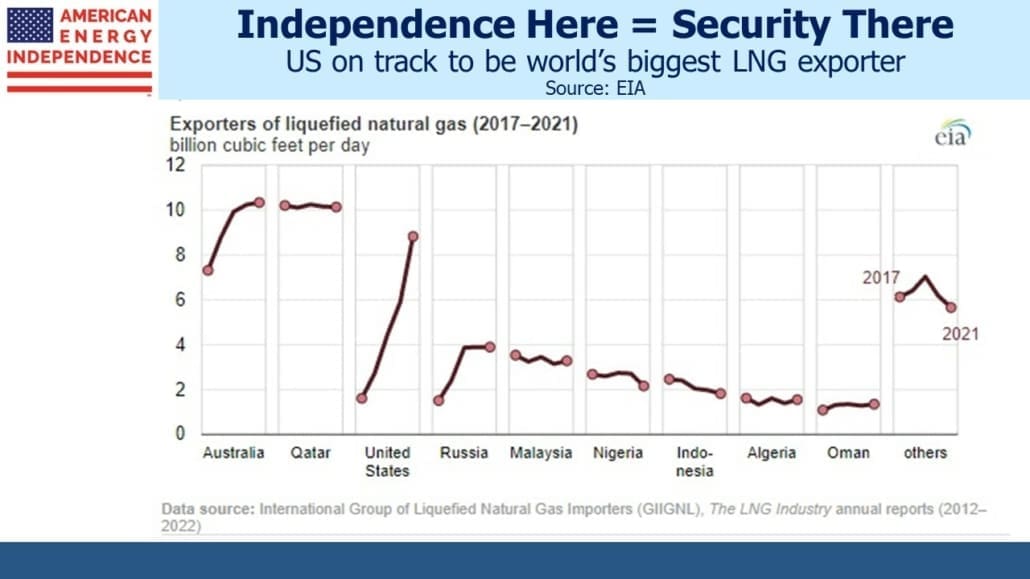

Putin continues to play a strong energy hand well. Natural gas flows to Germany on Nord Stream 1 are now 20% of capacity with the Russians blaming bureaucracy and western sanctions for the shortfall. By maintaining some flow of gas, Russia is maxkmizing German uncertainty around future flows and their ability to avoid rationing this winter. This continues to highlight the good long term prospects for exports of US Liquefied Natural Gas (LNG).

NextDecade announced another sale and purchase agreement, this time with Exxon Mobil to supply one million tons per annum of LNG over 20 years. The US became the world’s biggest exporter of LNG in the first half of this year, a mantle it’s unlikely to lose anytime soon. US natural gas remains a solid bet on Europe’s recently discovered need for energy security.

At the LPL conference last week several investors asked how the pipeline sector would respond if Republicans were to regain the White house in 2024, along with control of Congress which may even flip this coming November. Energy executives cheered Trump’s election in 2016, but energy investors have less fond memories of his administration. The shale bust ushered in financial discipline, augmented by Democrat policies on climate change that are unwittingly pro-investor.

Our affection for climate protesters and their ability to curb growth capex naturally causes some to wonder whether their possible loss of ascendancy might encourage more growth spending, jeopardizing divided hikes and buybacks. We think such an outcome is unlikely. Investment horizons are longer than the electoral cycle, and investors have welcomed the steady increase in distributable cash flow which provides 2X dividend coverage across the sector.

We have three funds that seek to profit from this environment:

Energy Mutual Fund Energy ETF Real Assets FundPlease see important Legal Disclosures.