Renewables: More Capacity, Less Utilization

The U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA) is generally apolitical – they’re not championing any single energy source. That may change under the new Administration, and they may become a shrill for renewables, but so far, they largely report data.

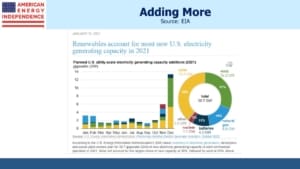

Yesterday their website carried Renewables account for most new U.S. electricity generating capacity in 2021, highlighting that 70% of the 39.7 Gigawatts (GW) of new capacity to be added is solar and wind.

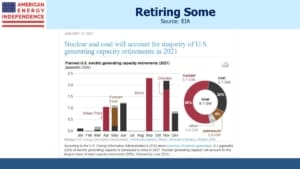

Recently they also ran with Nuclear and coal will account for majority of U.S. generating capacity retirements in 2021. The continued drop in coal is good news – its elimination is the fastest route to reduced emissions globally. This trend is unfortunately moving in the opposite direction in China and India, but at least in the U.S. we’re getting it right.

The drop in nuclear is not helpful in terms of lowering emissions, since it produces none. A realistic path towards fighting climate change includes using more nuclear, rather than relying fully on solar panels and windmills.

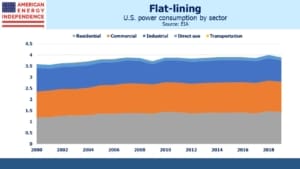

What’s notable is that we’re adding 39.7GW of generating capacity while retiring 9.1GW, for a net gain of 30.6GW. Total U.S. power generating capacity is 1,100 GW, so we’re adding around 3%. But U.S. power consumption for the past decade is flat. Energy intensity, the amount of energy consumed per $ of GDP, has been falling for decades in developed countries, reflecting ongoing energy efficiencies and the steady decline of manufacturing’s share of economic output.

So why is the U.S. increasing its energy capacity?

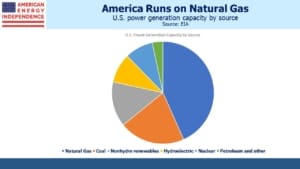

The 39.7GW being added is certainly expected to be used – otherwise the capital wouldn’t have been invested. Most likely, it reflects the lower utilization of renewables, which typically runs 20-30%. By contrast, baseload natural gas power plants run at 90% of capacity, with nuclear higher still.

The dismal truth that, for all the excitement about solar and wind, it takes more than 1 GW of solar capacity to decommission 1GW of coal power. This lower utilization is beginning to show up in the figures. The U.S. is net adding capacity while consumption is flat. Maybe enormous growth in electric vehicles will shift energy consumption from petroleum to electricity, but it’s likely we will gradually utilize less of our power generating capacity as the mix shifts.

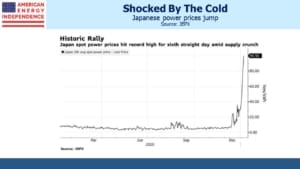

Comparing the cost per GW of different power sources doesn’t account for differences in utilization, which therefore flatters renewables. The need for back-up power to offset their intermittency is also normally overlooked.

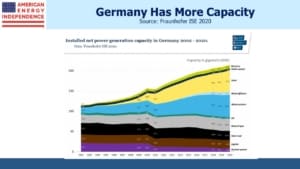

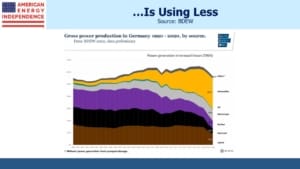

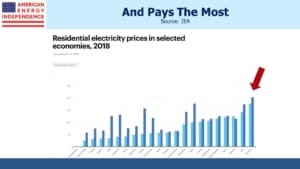

Germany has pursued renewables aggressively, adding capacity even while demand has been falling. Because of this, they also have among the highest electricity prices in the world. More of their power generation sits idle than in the past, because the windpower they’ve been adding has lower utilization. Watching the “Energiewend” (Energy Transition) has been instructive for the rest of us (see It’s Not Easy Being Green).

At least they’re not as bad as California, the state with America’s most expensive and least reliable electricity (see California’s Altruistic Carbon Policy).

Outside of California, electricity is cheap in the U.S. Some may believe there is plenty of room for prices to rise. If we are serious about climate change, prices should rise. Germany’s example shows where this can go. It’s not yet part of the climate change debate in America. It should be.

We are invested in all the components of the American Energy Independence Index via the ETF that seeks to track its performance.