Hedge Funds: Still Fleecing Investors with Expensive Mediocrity

A decade ago, the collapse of Lehman Brothers marked the psychological low of the 2008 Financial Crisis. Equity prices bottomed a few months later, in March 2009. Hedge funds had nimbly managed their way through the 2000-02 dotcom collapse, which led to substantial inflows over the next six years. By 2008 AUM had quadrupled, as less discerning investors piled in. In my 2012 book The Hedge Fund Mirage; The illusion of Big Money and Why It’s Too Good to be True, I showed that although early hedge fund investors had done very well, they weren’t that numerous.

The strong returns from the 1990s through 2002 had come with a much smaller industry. Consequently, hedge funds were far too big when the 2008 collapse came, and losses wiped out all the prior years’ profits. It meant that in the history of hedge funds, aggregate investor gains were offset by other investors’ losses. Hedge fund managers had profited; the clients had not. If all the money that’s ever been invested in hedge funds had been put in treasury bills instead, the results would have been twice as good. The Hedge Fund Mirage Turns Five showed that the book’s prediction of continued disappointment was right.

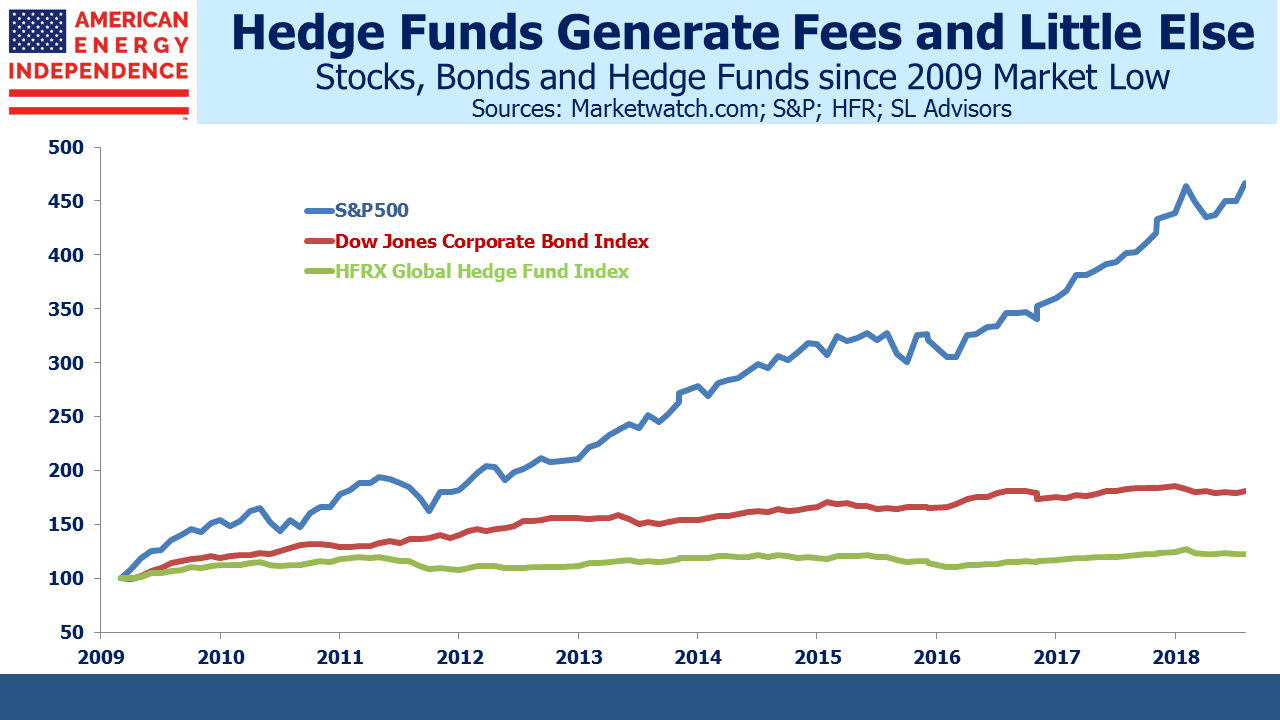

Having rudely reminded investors in 2008 that they take risk, one might think that hedge funds would have gained from the subsequent rebound in risky assets. Endure the downside, participate in the upside. Since the low in 2009 the S&P500 has returned 17.9% p.a. With dividends reinvested, it’s increased almost fivefold. Although it’s unfair to expect hedge funds to beat long-only stocks at that level, they’ve missed by such a margin that one wonders who still seriously recommends an allocation to the sector. The Dow Jones Corporate Bond index has delivered 6.4% p.a., three times the 2.1% annual return of hedge funds, even with a decade of ruinously low rates. Although worse investments are hard to find, hedge funds handily beat a fund launched in 2009 to follow Dennis Gartman’s newsletter recommendations.

Nonetheless, hedge fund managers have continued to do handsomely. Some of the smartest asset managers run hedge funds and they are highly talented at separating clients from their wealth via fees (see The Alpha Rich List Got 15% of Everything). Try thinking of anyone who became wealthy by being a hedge fund client.

Hedge fund AUM fell by half through the 2008 crisis, through investment losses as well as withdrawals from investors. Eventually some institutions saw through the false promises and left for good (see CalPERS Has Enough of Hedge Funds). But such is the attraction of investing with highly paid people that money flowed back in. Hedge fund promoters adapted their pitch. AR magazine, which published my original article on paltry returns, drew its name from covering the Absolute Return industry. When results showed that positive returns weren’t always assured, the goalposts were shifted and Relative Returns became the new mantra. But results turned out to be relatively worse than anything else. The shameless consultants moved to Uncorrelated Returns, which has turned out to be enduring since they’ve lagged just about everything outside of Venezuela. The July 2013 front cover of Bloomberg Businessweek needed few words.

It’s therefore no surprise that David Einhorn’s fund Greenlight is making its owners far richer than its clients. Investors in his $1.7BN flagship fund have endured almost four years of miserable performance, with a drop of 36% since November 2014. Like virtually all hedge fund managers and the industry overall, Greenlight was better when it was smaller.

Don’t blame David Einhorn. It’s a common story and he’s only the most recent former star to crash to earth. Einhorn must sincerely believe in his ability. Blame the enablers, the consultants and other advisors who drive clients to hedge funds. They still fail to recognize that high returns come from limited opportunities, and that competition from increased AUM drives them down. Last year Ted Seides (then, but no longer, co-CIO at Protégé, a fund of hedge funds) famously lost his 2007 $1million bet with Warren Buffett that hedge funds would outperform the S&P over the subsequent decade – and that was made before the financial crisis decimated stocks (see Buffett’s Hedge Fund Bet).

Protégé owner Jeff Tarrant later argued that a decade of lunches and dinners with Buffett following the bet made it money well spent – and based on what an auctioned Buffet lunch goes for, he has a point. But drawing attention to hedge fund performance is rarely a good marketing strategy, so the Ted Seides bet was ill-advised. The poor guy must have actually believed he’d win, betraying a gaping absence of investment acumen and common sense.

There are some thoughtful hedge fund investors around that add value for their clients. A few of them are friends of mine. They’re the ones who recognize the conflict of size with performance, adapting their portfolios to avoid the crowd. But the majority of hedge fund promoters orbit the truly talented to whom they only aspire, promising their gullible investors gold over the rainbow that they must know really isn’t there.