Energy Transfer: Cutting Your Payout, Not Mine

/3 Comments/in Midstream Energy Infrastructure/by Simon LackToo few writers covering energy infrastructure admit to the many distribution cuts inflicted on MLP holders. Instead, they identify numerous other problems whose resolution will draw in buyers. Incentive Distribution Rights (IDRs), the payments made by MLPs to their General Partners (GP), have drawn scorn for the past couple of years. Eliminating them is fashionable and now virtually complete, with only a handful of holdouts. Other solutions include self-funding growth projects. Common practice was for MLPs to pay out most of their cash and raise equity for new projects. It worked until the new projects became big. The Shale Revolution was responsible for that. Selling non-core assets is another piece of advice – it’s rarely controversial. Few companies admit that any assets are non-core, until selling them.

All this free advice is directed both publicly and privately to help draw in new investors and lift stock prices. What’s rarely mentioned are the widespread and substantial cuts in distributions that have alienated the income-seeking MLP investor base. Alerian has a chart showing “AMZ Normalized Distributions Paid”, which shows a cumulative 25% cut 2015-17, if you do the math. Dividends on AMLP are down 34% from their high in 2014, although you won’t find this on their website. Promises have been broken, and the buyers know this.

One reason others don’t dwell too much on this issue is that many distribution cuts have been via mergers and simplifications. When a lower yielding GP acquires its MLP, the MLP investors are subjected to a “backdoor” distribution cut through owning a new security with a lower yield than the one they gave up.

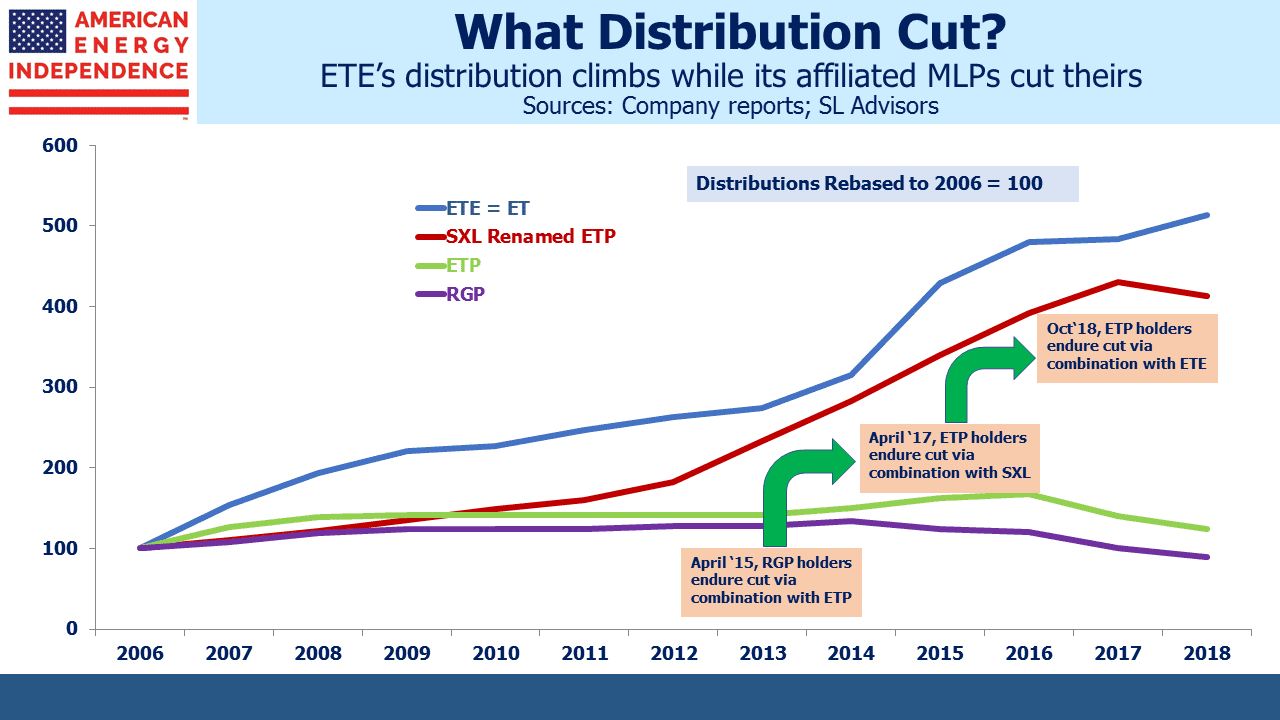

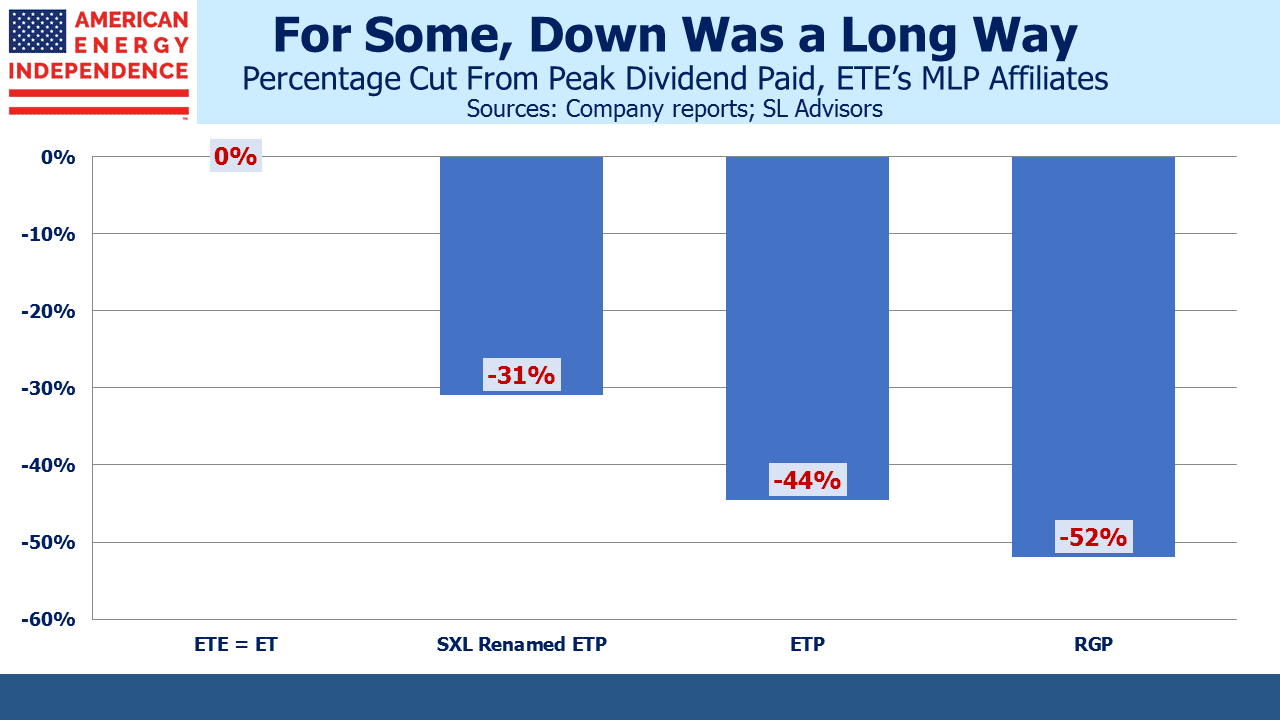

Energy Transfer has excelled at imposing such “stealth distribution cuts”. Over the past four years they’ve rolled four publicly traded entities into one. In each case, the lower-yielding entity acquired the higher-yielding one, resulting in a lower distribution for investors in the acquiree.

What’s striking is to overlay the normalized distribution history of the four entities: Energy Transfer Equity (ETE), Energy Transfer Partners (ETP), Sunoco Logistics (SXL) and Regency Partners (RGP). ETE is the surviving entity, now renamed Energy Transfer (ET).

ETE investors have seen a five-fold increase in distributions since 2006, a 13% compounded annual growth rate. They’ve increased distributions every year. That shouldn’t be surprising, because ETE was always the vehicle of choice for CEO Kelcy Warren and the management team. SXL holders had a good run – in 2016 they folded in higher-yielding ETP but retained the ETP name, which gave them a 14% distribution growth rate to that point. But then they were “Kelcy’d”, as ETP adopted ETE’s lower payout in a subsequent combination, leading to a 31% effective cut. Original investors in ETP and RGP did worse.

ET’s price peaked in 2015 (it was ETE back then), when Kelcy embarked on his ultimately unsuccessful attempt to buy Williams Companies (WMB). It’s a measure of how far sentiment has fallen, in that ETE’s yield briefly dipped below 3% in May 2015. Since then, its distribution has risen from $1.02 to $1.22. They dodged the WMB deal, have reduced leverage, completed the Dakota Access Pipeline and expect to cover their distribution by 1.7-1.9X next year. Nonetheless, today ET yields 8.5%, with an estimated 2019 Distributable Cash Flow yield of 15.9%. No wonder Kelcy Warren is back in buying the stock.

It’s true that ET’s management has earned a reputation for self-dealing. During the protracted WMB merger negotiations , ETE issued very attractive convertible preferred securities to the senior executives, but didn’t make them available to other ETE investors (see Will Energy Transfer Act with Integrity?). Although they won the resulting class action lawsuit, it’s clear that if management can get away with something that benefits them but not shareholders, they will. Even so, the current valuation seems excessively pessimistic.

Kinder Morgan (KMI) and Plains All American (PAGP) drew unwelcome attention for each delivering two distribution cuts to their investors. KMI’s first cut was through combining with their MLP in the technique later used by ETE. They followed this up with a second, unambiguous cut in response to rating agency concerns over leverage. PAGP’s management administered two direct cuts, stunning investors both times. Oneok (OKE), Targa (TRGP), Semgroup (SEMG), and Enlink (ENLC) all folded in their respective MLPs, delivering backdoor distribution cuts to their MLP holders but maintaining their dividends at the GP level. But many others avoided cutting their dividends at all. Antero Midstream (AMGP), Tallgrass (TGE) and Western Gas (WGP) all rolled up their MLPs with no change in payouts.

None of the Canadian midstream companies cut their dividends, reflecting their more conservative approach. This highlights that the distribution cuts were due to the flawed MLP practice of paying out virtually all available cash flow, relying on tapping the capital markets for growth projects. There were a few exceptions, but in general MLP distribution cuts were not due to deteriorating fundamentals in the midstream sector.

MLPs are still cutting payouts. Distributions on AMLP, which is MLP-only and tracks the Alerian MLP Infrastructure Index, are down 6.9% this year. By contrast, distributions on the American Energy Independence Index, which includes the biggest North American pipeline corporations and MLPs and is therefore more representative of the overall sector, are up 6.6%.

We are invested in AMGP, ENLC, ET, KMI, OKE, PAGP, SEMG, TGE, TRGP, WGP and WMB. We are short AMLP.

SL Advisors is the sub-advisor to the Catalyst MLP & Infrastructure Fund. To learn more about the Fund, please click here.

SL Advisors is also the advisor to an ETF (USAIETF.com).

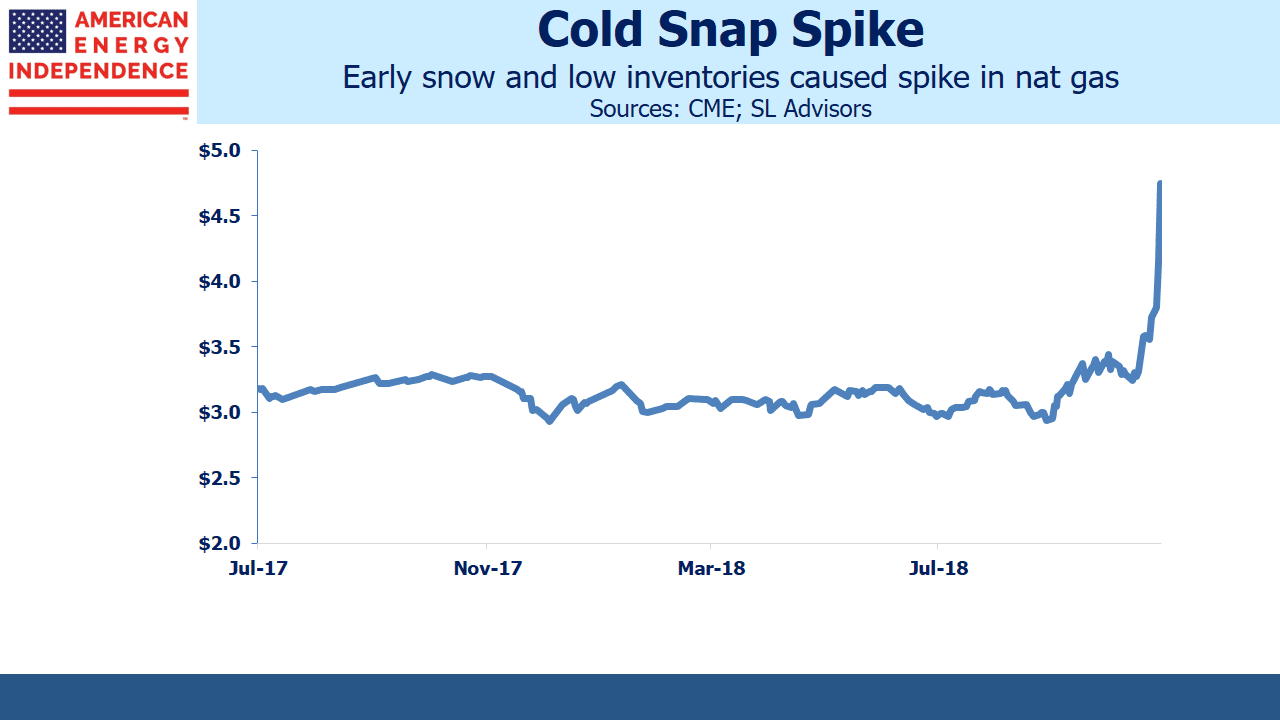

FANG Goes Bang

/1 Comment/in Global Issues/by Simon Lack“FAANG” stocks (Facebook, Amazon, Apple, Netflix and Google, now called Alphabet) were rising for most of the year. For investors who didn’t find that exciting enough, BMO Capital Markets Corp helpfully issued the MicroSectors FANG+ 3X Leveraged ETN (FNGU). As the name suggests, it gives you three times the daily return on these, plus another five for good measure (Alibaba, Baidu, NVIDIA, Tesla and Twitter). That I don’t personally know any buyers reveals more about the sedate company I keep, because there’s clearly a ready market for leveraged ETNs. Last week DGAZ, Credit Suisse’s ETN designed to provide 3X the downside to natural gas, collapsed as natgas soared, losing 81% of its value over the past month.

The Fact Sheet for FNGU warns it’s, “not suitable for investors with longer-term investment objectives.” What other investor types are there? Because such securities maintain constant market exposure, they have to rebalance every day. Leverage magnifies the effect of compounded returns. A stock that rises and falls by 1% on alternate days will lose half its value in 13,860 days. If it moves 2% this only requires 3,465 days, while 5% takes 553 days. You get the picture. One can think about the half-life of these leveraged products – how long would it take them to lose 50% given historic volatility. With daily moves in natgas of 1.2%, DGAZ had a half-life of 1,087 days. The recent spike in prices has hastened its demise.

It’s not only DGAZ buyers who lost big. The author of The Complete Guide to Option Selling posted a video on YouTube in which he tearfully explains why his hedge fund has just been wiped out by the “rogue wave” in natgas.

Leveraged ETFs and ETNs have their critics, and scarcely need one more. SEC officials have individually criticized them but stopped short of withholding approval.

The point is that the violent losses in FNGU highlight far more substantial recent losses for investors in the underlying stocks, and more broadly in growth-style investing. Since the 2016 Presidential election, equity returns have been dominated by a narrow group of growth stocks. At its peak in June, the FANG+ index had risen by 125% from its election-day level. Although the FANG+ group has been in retreat since then, the S&P500 Growth ETF (SPYG) continued to outperform. As recently as late September, SPYG had risen by 52% since the 2016 election, beating the S&P500 Value ETF (SPYV) by 22%.

Since then, SPYG’s lead over SPYV has been halved. We are approaching correction territory, defined as a 20% pullback from the highs. FANG+ is already there, at -23% from its June high. The Nasdaq Composite Index not far away, down 15% from its high set in August. while SPYG is -12%. The S&P500 has pulled back 10%, with SPYV falling a more modest 8%.

There’s a shift under way. With growth investors certainly having had the better of things in the past couple of years, there are still profits to protect. But it’s rarely easy valuing former highfliers when momentum is turning. Value stocks by definition have firmer valuation support. In addition, their investors are less likely to sell in a falling market. They own what they do because they like the valuation, and are less dependent on others liking it more to generate a return. Low volatility stocks, having lagged the S&P500 by 5% for the year through September, are now outperforming the S&P500 by 4%.

This leads to one of today’s great value opportunities – U.S. pipeline stocks. The names in the American Energy Independence Index offer a 10.9% yield on 2019E Distributable Cash Flow (DCF, which is free cash flow ex-growth capex), up 13% over 2018. This is analogous to the Funds From Operations (FFO) commonly used in real estate, as we showed in a recent blog (see Kinder Morgan: Still Paying for Broken Promises). The index has a current dividend yield of 6.25%, and we expect dividends to grow 8% next year.

Growth stocks may resume their upward trajectory, but the recent volatility has shown how quickly two years of outperformance versus value can quickly reverse.

SL Advisors is the sub-advisor to the Catalyst MLP & Infrastructure Fund. To learn more about the Fund, please click here.

SL Advisors is also the advisor to an ETF (USAIETF.com).

Oil and Gas Take Center Stage

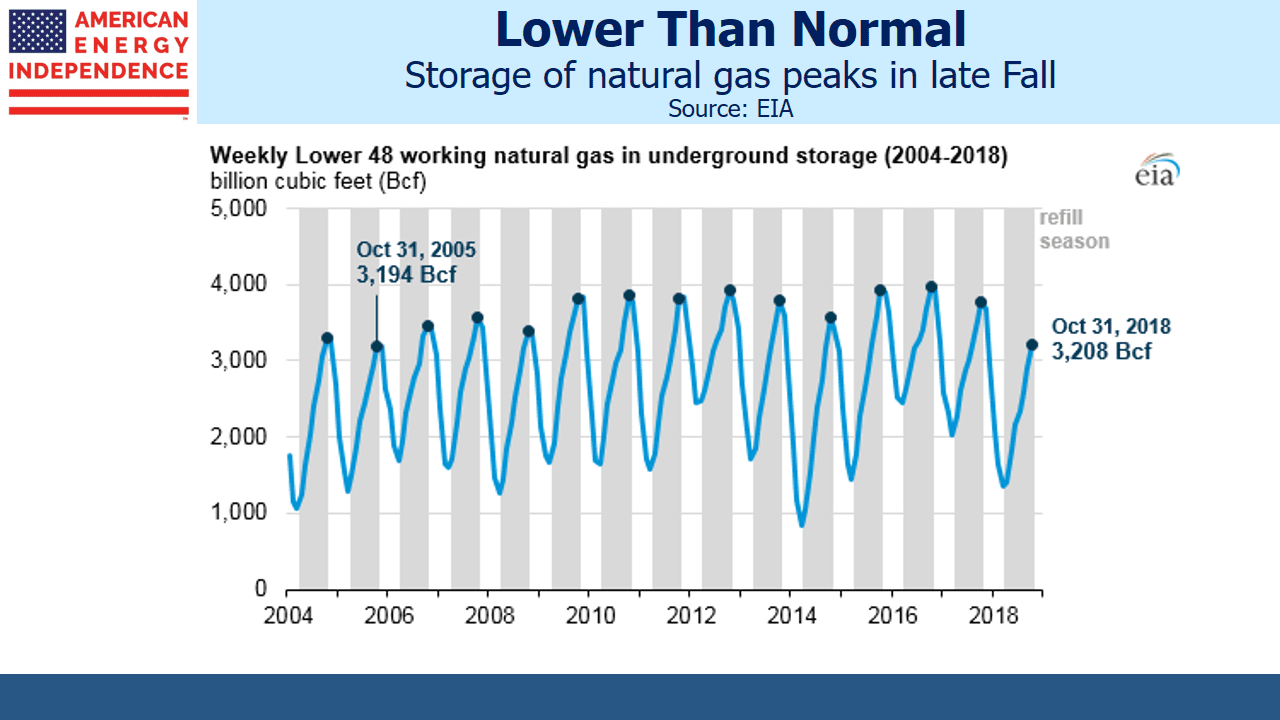

/1 Comment/in Midstream Energy Infrastructure/by Simon LackIf pipeline stocks moved with natural gas rather than crude oil, their long-suffering investors could look back on a good week. On Tuesday crude was down $5 per barrel for the week, before recovering $2 by Friday. It’s tumbled $20 since early October, bringing Brent Jan ’19 to $66. By contrast, the Jan ’19 natural gas contract stormed out of its $2.90 to $3.50 per Thousand Cubic Feet (MCF) range that has constrained it all year, almost reaching $5 on Wednesday. Rarely have oil and gas been so disconnected.

The energy sector moves to the rhythm of crude. It’s is a global commodity, relatively easy to transport, which allows regional price discrepancies to be arbitraged away. Oil can move by ship, pipeline, rail or truck. Transportation costs vary from a few dollars per barrel for pipeline tariffs or waterborne vessel to $20 or more by truck. Although Canada’s dysfunctional approach to oil pipelines has led to deeply depressed prices, in most cases transport costs are a portion of the cost of a barrel.

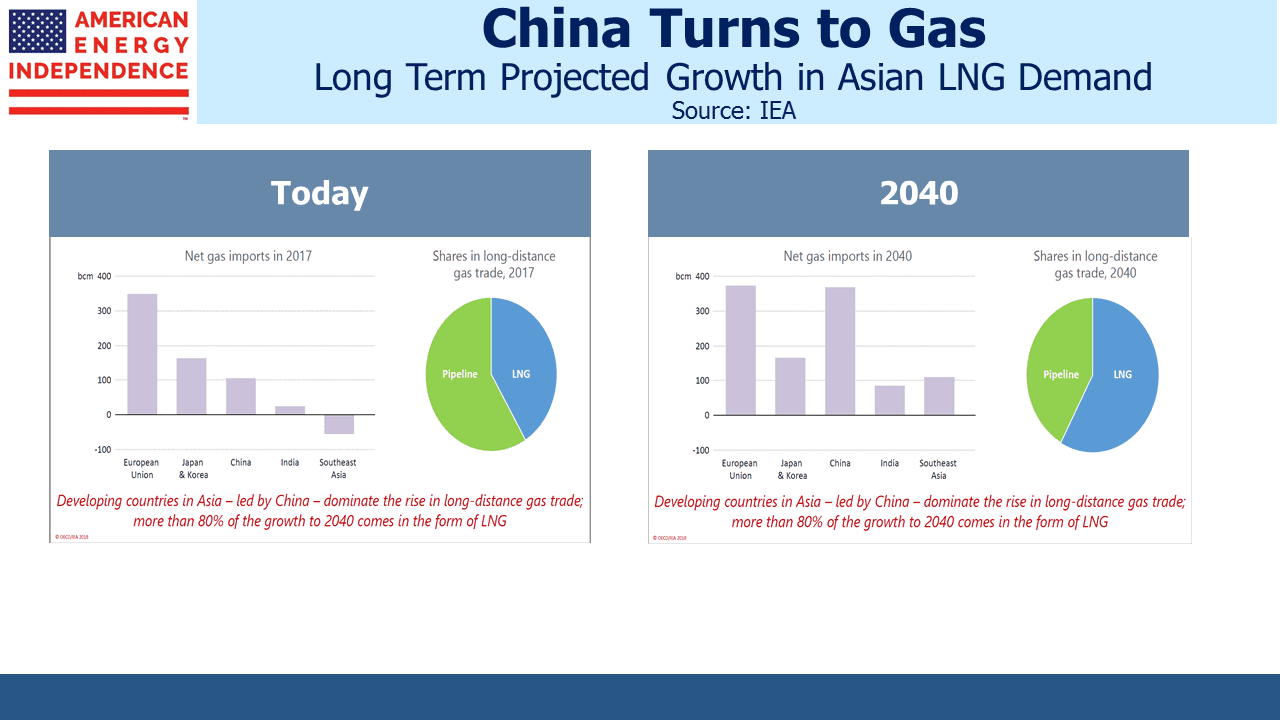

By contrast, natural gas (specifically methane, which is used by power plants and for residential heating and cooking) generally only moves through pipelines or on specially designed LNG tankers in near-liquid form. Long-distance truck transportation isn’t common because liquefying methane to 1/600th of its gaseous volume requires thick-walled steel tanks. Methane moved as Compressed Natural Gas (CNG) is only 1% of its normal volume (i.e. requires 6X more storage volume than LNG) which generally renders long-haul truck transport uneconomic. LNG shipping rates from the U.S. to Asia are $5 or more per MCF, more than the commodity itself. The 10-15,000 mile sea journey is worth it because prices in Asia are $8-15 per MCF, compared with normally around $3 per MCF in the U.S.

The result is that natural gas prices vary by region far more than crude oil.

There are price discrepancies within the U.S. too. The benchmark for U.S. natural gas futures is at the Henry Hub, located in Erath, LA. This is where buyers of $5 per MCF January natural gas can expect to take delivery. By contrast, 700 miles west in the West Texas Permian basin, natural gas is flared because there isn’t the infrastructure to capture it. Gas is flared because it’s worthless. Mexican demand is coming, but construction south of the border is running more slowly than expected.

The price dislocation in U.S. natural gas highlights the ongoing need for additional pipeline and storage infrastructure. Price differences in excess of the cost of pipeline transport translate into pipeline demand. Although the spike in Jan ’19 natural gas futures reflects a temporary supply shortage that can’t be alleviated by a new pipeline given multi-year construction times, such events are generally good for midstream energy infrastructure businesses.

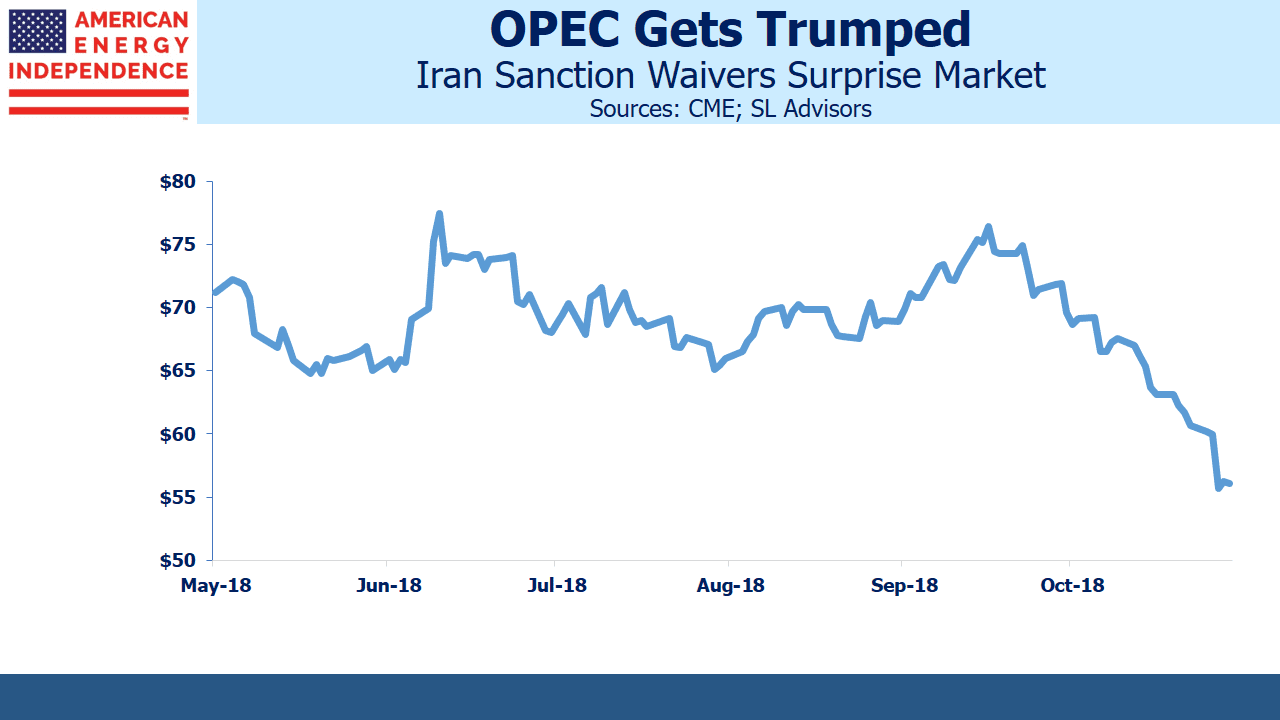

The oil price dislocation was at least partly due to hedging of option exposure by Wall Street banks that had sold put options to producers, such as Mexico. It has very little to do with midstream infrastructure. Having fretted for months over U.S.-imposed sanctions on Iran, the market was surprised by waivers that are softening the blow for Iran’s oil customers. It’s likely to create a reaction (see Crude’s Drop Makes Higher Prices Likely).

Long term forecasts of natural gas demand are less varied than for crude oil, and are driven by Asian consumption at the expense of coal for electricity production. Crude oil demand forecasts vary more, generally because of differing expectations for electric vehicle sales. Although both are growing, a bet on natural gas looks the safer of the two.

Nonetheless, crude oil moves the energy sector and U.S. pipeline stocks tag along. On Tuesday when crude oil was -6.6%, the S&P Energy ETF (XLE) and Williams Companies (WMB) both slid 2.3%. Jan ’19 natural gas was +9.1%. WMB derives virtually all its value from transporting and processing natural gas and natural gas liquids. Its inclusion in XLE probably causes it to move with the sector more than its business would suggest.

3Q18 earnings for pipeline companies have been largely equal to or better than expectations. The fundamentals remain strong – investors continue to ask when sector performance will reflect this. Although the recently declared dividend on the Alerian MLP ETF (AMLP) is 34% below its 2014 level, we expect corporations will start increasing dividends, with the American Energy Independence Index likely to experience 10% growth in 2019.

We are long WMB and short AMLP.

SL Advisors is the sub-advisor to the Catalyst MLP & Infrastructure Fund. To learn more about the Fund, please click here.

SL Advisors is also the advisor to an ETF (USAIETF.com).

Crude’s Drop Makes Higher Prices Likely

/0 Comments/in Global Issues/by Simon LackCrude oil just set a record of sorts, by falling for eleven consecutive days (as of this morning). Fears that sanctions on Iran would cause a supply shortage, leading to a price spike, now seem unfounded. Not long ago, many were surprised at the high degree of compliance. France’s energy giant Total’s CEO said it was, “…impossible for big energy firms to work in Iran.”

The big stick America wields on this issue is access to the U.S. financial system. If a company is deemed to be trading with Iran, it can find itself unable to conduct financial transactions in US$. This is a surprisingly powerful tool, since a substantial amount of trade is conducted in our currency. Total concluded that being unable to transact in US$ would be too disruptive to contemplate.

In the summer, the U.S. appeared to be taking an uncompromising approach, and Iranian crude exports were forecast to fall from 2.5 Million Barrels per Day (MMB/D) to as little as 1 MMB/D. Crude oil futures correspondingly rose. Pressure was put on Saudi Arabia to provide offsetting increased output, as the Administration fretted over high gasoline prices before the midterms.

More recently, waivers granted by the White House to eight importers of Iranian crude have calmed fears of a price spike. China and India, who are both continuing to buy Iranian crude as a result, imported over 1 MMB/D last year. As a result, the January ’19 Brent Crude month futures contract has slid from $86 in early October back to $68 where it was in the Spring. For now, it seems that the Iranian sanctions aren’t that significant.

Saudi Arabia probably expected the U.S. to be stricter in following through on sanctions, and was surprised by the waivers. They have just reduced December exports by 0.5 MMB/D. The Saudis surely expected to be selling oil at higher prices a month ago. Recent data shows that Saudi exports to the U.S. have been falling, and floating storage (i.e. crude on tankers in transit) is the lowest in four years. Some believe that Saudi Arabia is unable to sustain production above 10.6 MMB/D or so without damaging their oilfields.

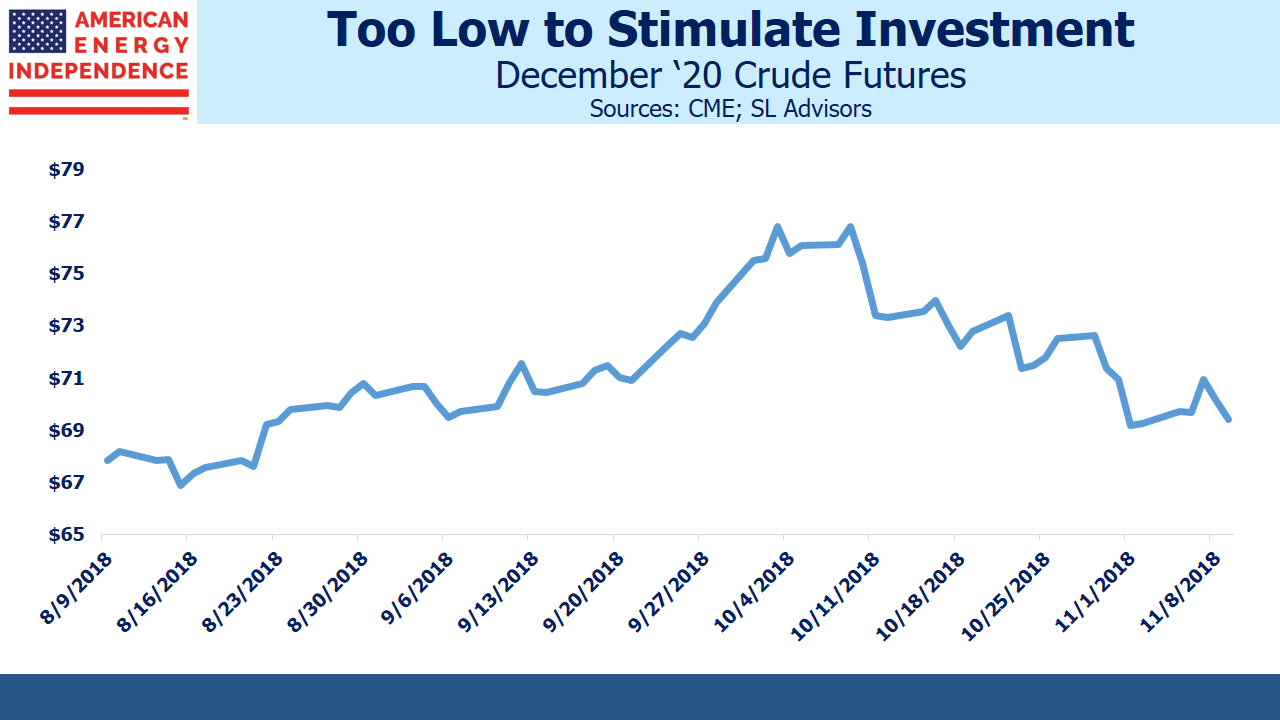

Although the gyrations of the front month futures contract have commanded attention, crude prices farther out have moved much less. The December ’20 futures contract fell from $76 to $70. Fear of sanctions had caused backwardation (near contracts higher than farther out ones), and this has corrected.

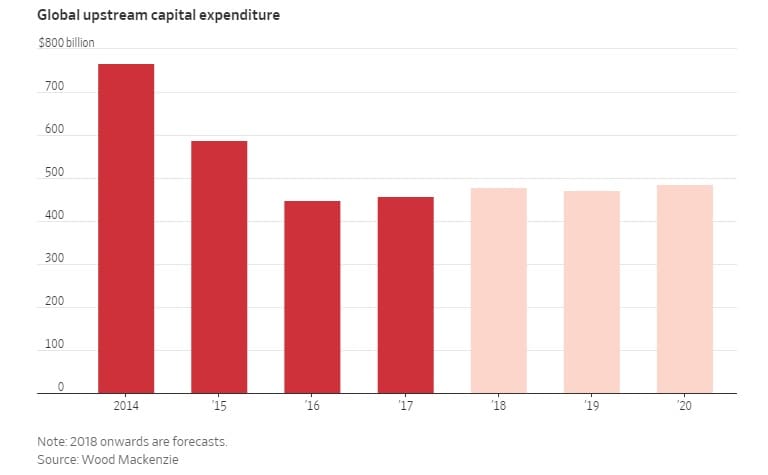

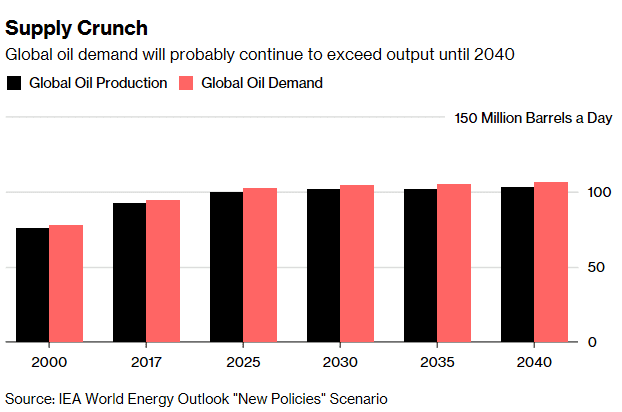

Investments in conventional oil production are driven by the price of crude expected to prevail over the life of the project. The front month gets the attention, but it doesn’t drive the decision. Because new oil projects take several years to reach production, many in the industry continue to worry that falling investment levels will eventually cause higher prices. The International Energy Agency (IEA) recently released their World Energy Outlook. They warn of a looming supply crunch, with the world seemingly too reliant on increasing U.S. production to meet demand growth. Investment spending collapsed during the 2015-16 industry downturn, and remains more than one third lower than it was in 2014. Discoveries of conventional hydrocarbon reserves are correspondingly down.

Crude oil along the futures curve is still at levels that have drawn repeated warnings of future supply shortfalls. Moreover, Saudi Arabia is finding that the U.S. administration ultimately wants low prices, with Trump recently tweeting, “Hopefully, Saudi Arabia and OPEC will not be cutting oil production. Oil prices should be much lower based on supply!” Expecting Americans to tolerate higher pump prices so as to pressure Iran is an unlikely strategy for any president to pursue. But Saudi Arabia needs higher prices to balance their budget. These conflicting goals will continue to impact oil prices.

Low investment means higher prices are likely over the intermediate term; perhaps sooner, based on the drop in Saudi exports.

Valuing MLPs Privately — Enterprise Products Partners

/3 Comments/in Midstream Energy Infrastructure/by Simon LackMLP valuations show that the trust of the traditional MLP investor has been lost, perhaps irretrievably. In Kinder Morgan; Still Paying for Broken Promises, we showed how that company’s history of investor abuse via two distribution cuts and an adverse tax outcome continues to weigh on its stock price. In Magellan Midstream: Keeping Promises But Still Dragged Down by Peers, we showed how even well-run companies that have honored promised distributions remain hampered by the abuse of others in the sector. The Alerian MLP ETF (AMLP) lowered its quarterly dividend again last week, by 7.5%. It’s now 34% below its 2014 high. The persistent cheapness of pipeline stocks reflects understandable wariness by MLP investors, who bought for the tax deferred income and had it partially removed.

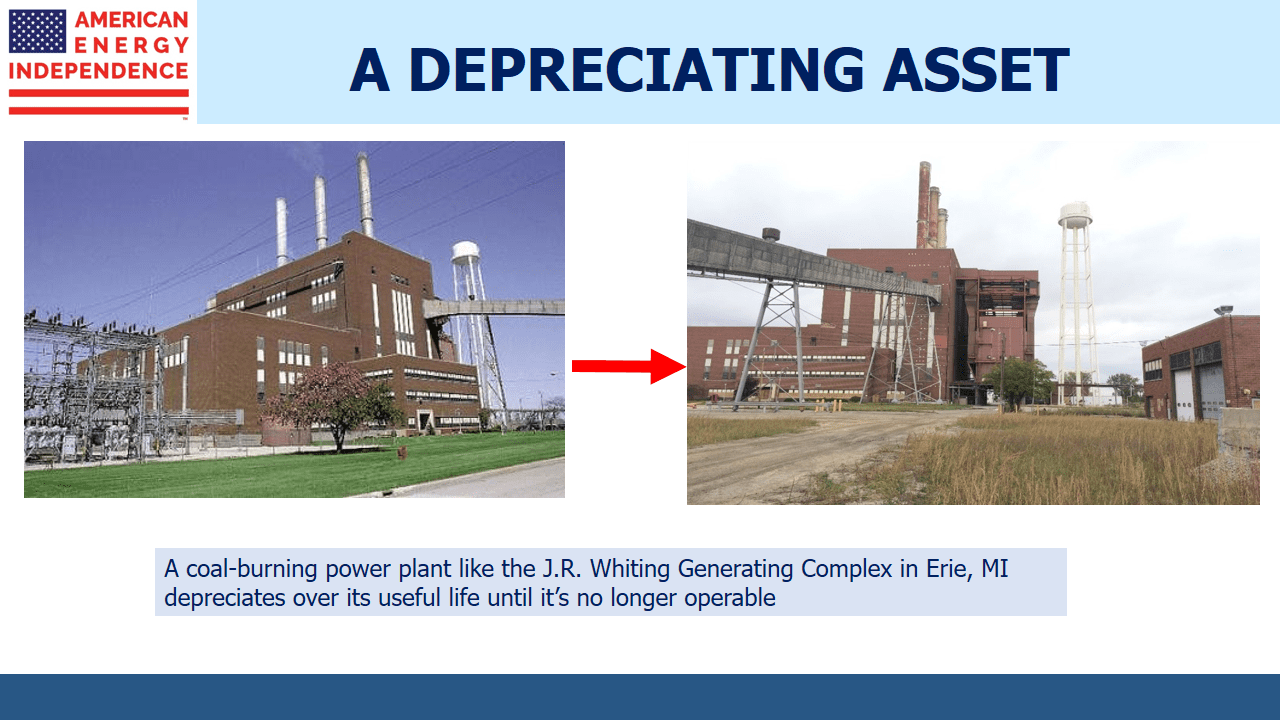

Valuing such stocks on yield alone inadequately captures the past history of distribution cuts. Another common metric, EV/EBITDA (Enterprise Value/Earnings Before Interest, Taxes, Depreciation and Amortization), is a blunt tool making little distinction between appreciating versus depreciating assets, or long term versus short term contracts.

Private equity buyers tend to look at cashflows. Using Enterprise Product Partners (EPD) as an example, Discounted Cash Flow (DCF) analysis reveals underappreciated value. DCF is often used to refer to an MLP’s Distributable Cash Flow, cash available for paying distributions to investors. To avoid confusion, in this article we will only use DCF as initially defined, the present value of future cashflows

EPD is the largest MLP. It is one third owned by the Duncan family and its well respected management team is ably led by Jim Teague. Their pipelines, storage assets and processing facilities handle crude oil, natural gas, natural gas liquids (NGLs) and refined products. They have a huge presence in along the gulf coast and include vertically integrated businesses that, for example, capture, moves, fractionate and export ethane.

EPD’s P/E ratio is unremarkable. Based on a consensus estimate of $1.67 for 2019, they trade at 16X, approximately the same multiple as the S&P500.

EPD’s EV/EBITDA is 11X. By comparison, KMI is 9.4X (penalized for past transgressions) while Oneok Inc (OKE) is at 14.7X, still feeling the love after last year’s successful conversion from an MLP to a corporation. Magellan Midstream (MMP), subject of last week’s blog, is 12.6X. On this measure, EPD could be described as moderately cheap versus its peer group.

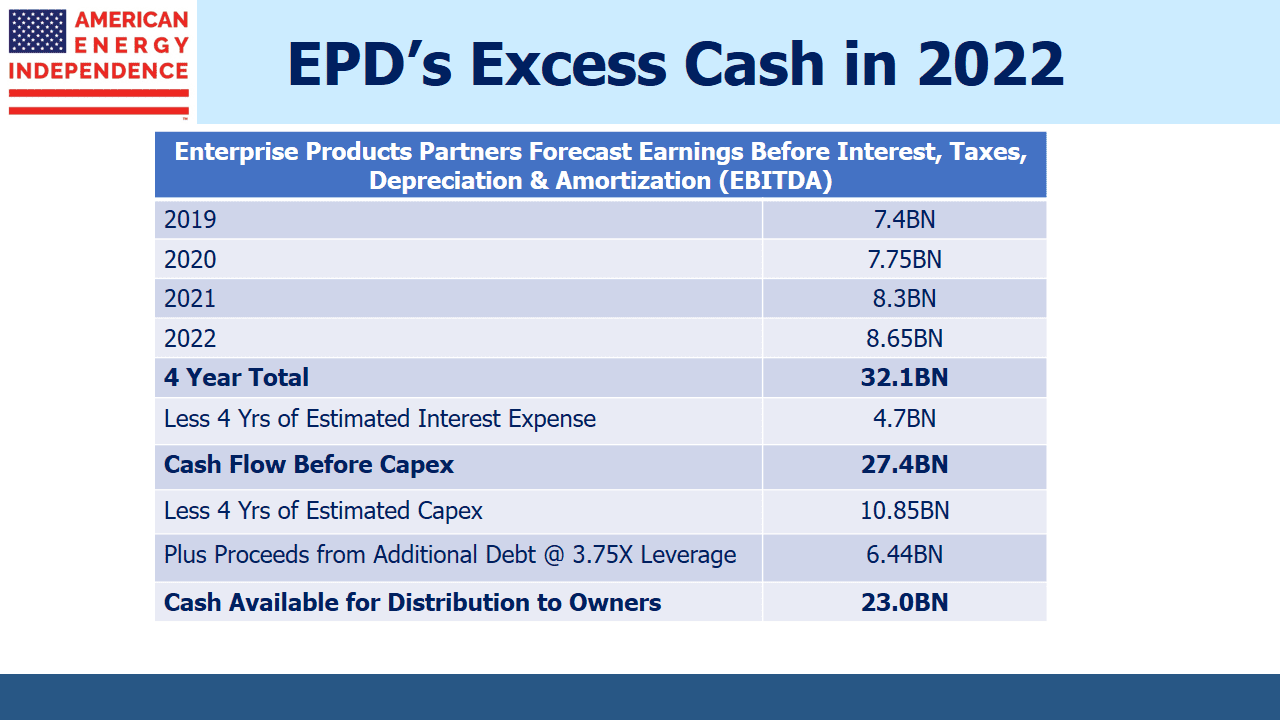

While those traditional measures of valuation are unexciting, DCF analysis reveals a truly undervalued asset. Below is simplified look at cash flow analysis based on consensus EBITDA estimates:

2018: $7.0BN

2019: $7.4BN

2020: $7.75BN

2021: $8.3BN

2022: $8.65BN

===========

2019-22 Total $32.1BN

Financing EPD’s $26BN in debt costs $1.17BN (4.5% borrowing rate) annually. This year they’ll generate around $5.83BN in cash before taxes (which they don’t pay as an MLP). Depreciation and Amortization are non-cash expenses that typically don’t reflect the growing value of their assets, which is why earnings multiples such as P/E aren’t that useful.

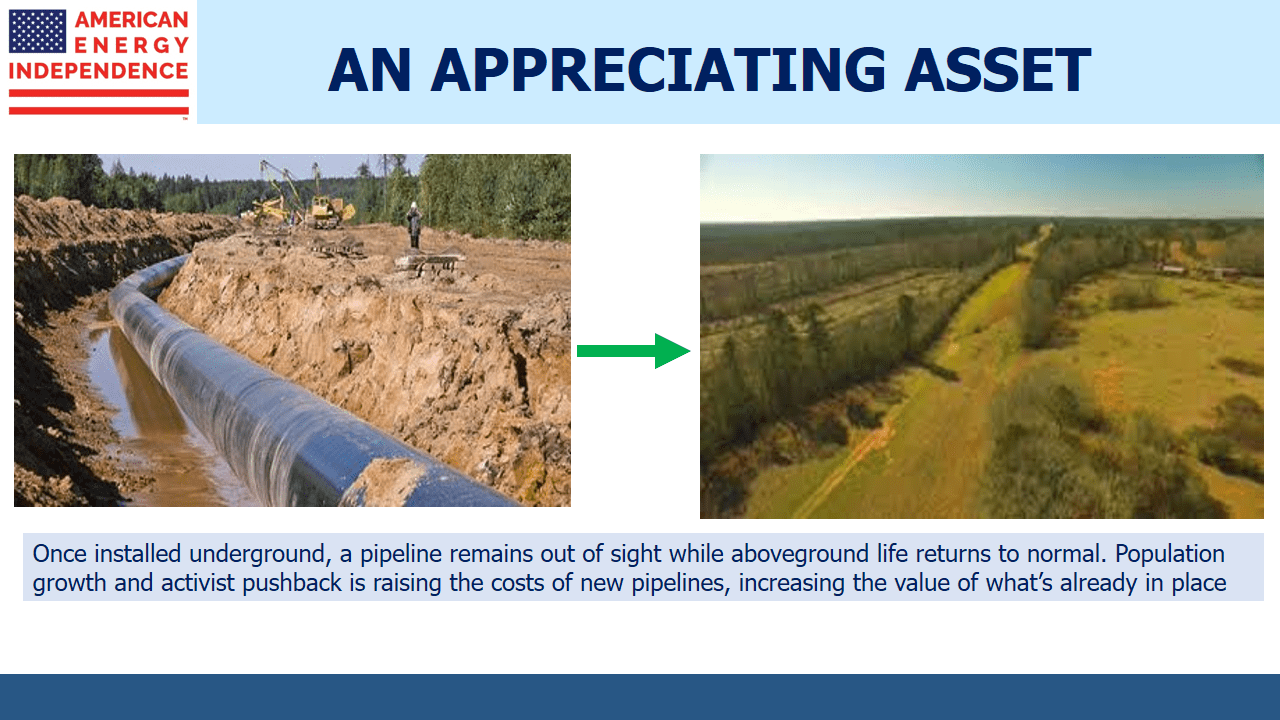

For example, EPD owns underground salt caverns in Mont Belvieu, used for storing NGLs. This is wholly different than, say, a coal-burning power plant, which is why EV/EBITDA comparisons with utility stocks make little sense. Pipelines, when properly maintained, generally appreciate in value. As communities grow up around and over them, and other pipelines link into them, it becomes prohibitively expensive to build competing infrastructure.

With a Debt:EBITDA ratio of <4.0X, EPD is comfortably investment grade with a strong balance sheet. This allows them to rely on debt to finance their backlog of new projects. The Shale Revolution continues to create demand for new infrastructure in support of America’s growing production. Companies like EPD are financing and building it.

EPD’s backlog of new projects over the next four years is estimated at $9.5BN and they’re expected to spend $1.35BN in maintenance capex, which is money spent on their existing assets to maintain their capability.

Because their EBITDA is growing, by 2022 they’ll be able to carry debt of $32.44BN (2022 EBITDA of $8.65BN multiplied by their 3.75X desired Debt/EBITDA multiple – the low end of their guidance range of 3.75 to 4.0x Debt/EBITDA). That’s $6.44BN more than their current debt, which means they could, if they chose, borrow to finance ~60% of their $9.5BN in new projects and $1.35BN in maintenance capex, allowing more cash to be returned to equity holders. Only $4.4BN needs to be sourced from cash generated, so there is no need to issue dilutive equity.

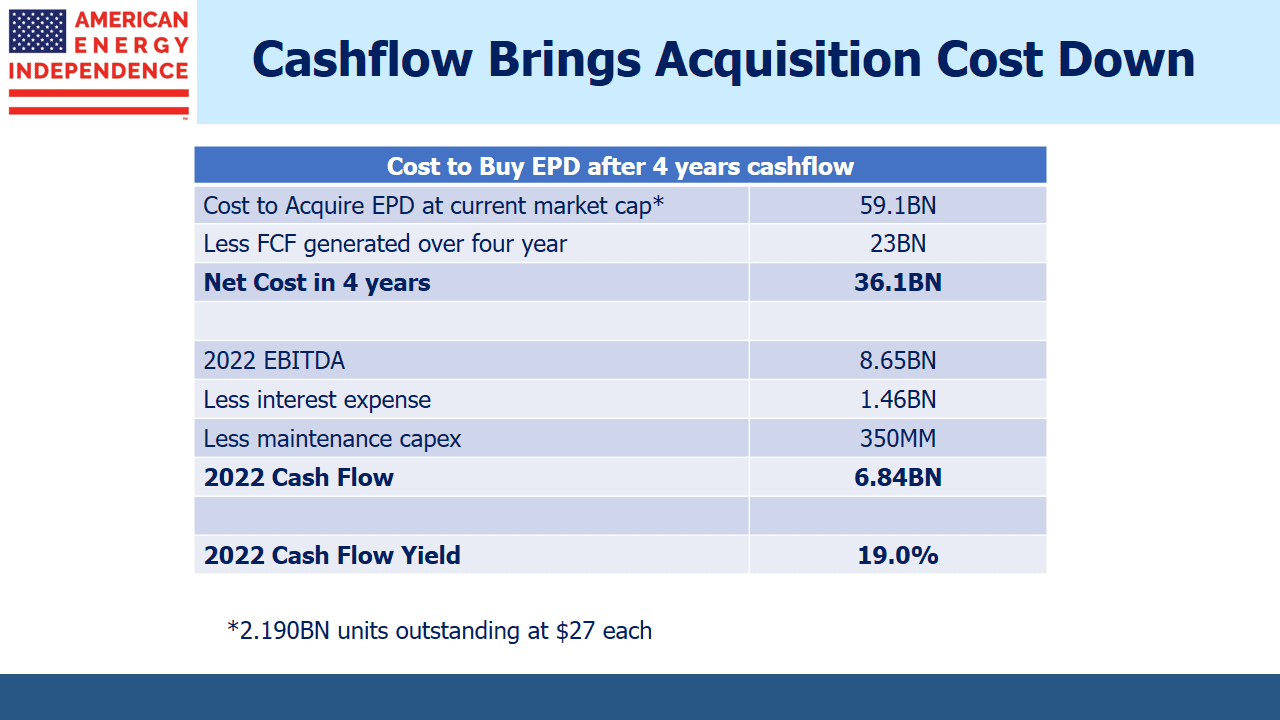

Since new projects can be self-financed, it simplifies the valuation of the business. Suppose you had $59BN in cash with which to acquire the company at its current market capitalization (although as you’ll see, it’s doubtful the Duncan family would sell).

Over four years, the business will generate $32.1BN in EBITDA, less its interest expense of $4.7BN (4 times $1.17BN) and new investments funded from cash flows of $4.4BN, leaving $23BN. Returning this excess cash reduces the purchase price to $36BN by 2022. Deduct annual interest expense of $1.46BN (since there’s now more debt because of the growth projects) and maintenance capex of $350M, and the business is generating $6.84BN in cash, annually. On the $36BN purchase price, that’s a 19% cash flow yield.

Even half that cash flow yield would be attractive, which would value EPD 20% above its current market cap after paying out ~40% of its market cap in cash.

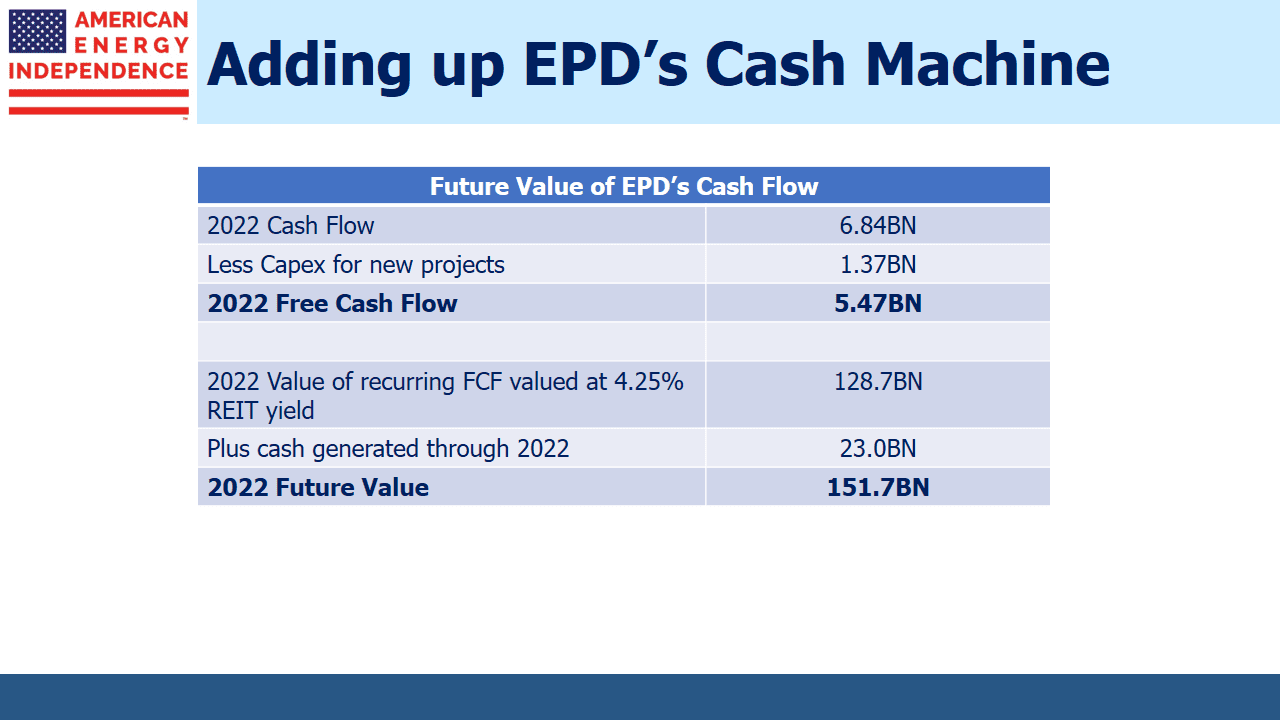

Future growth projects add further to the potential value. New energy infrastructure projects generally have required returns from as low as 10-12% to 20%+, depending on the degree of risk. Suppose EPD is able to reinvest 20% of its $6.84BN in annual cash, or $1.37BN, into new projects that have an expected unlevered return of approximately 14.3%. This equates to an EBITDA multiple of 7X (i.e. $100 invested to earn $14.30 is a multiple of 100/14.3, or 7) which is in the middle of the expected range for EPD’s current projects of 6-8X. Sticking to their 3.75X leverage multiple, they could finance 54% of the project with debt (i.e. 3.75X desired debt multiple divided by 7X project multiple). The rest would come from equity, which would be sourced from current cashflow.

The result would be an investment of $1.37BN in equity ($6.84BN times 20%) along with $1.58BN in debt, for a total of $2.95BN. The 14.3% expected return on the $2.95BN project would generate $421MM annually, contributing to future EBITDA growth. After interest expense of $71MM (same interest rate of 4.5% assumed throughout) and maintenance capex of $21MM (estimated to be 5.0% of EBITDA), there would be $329MM of incremental cash flow for distribution.

By 2022 the business would have $5.47BN in annual distributable cash flows ($6.84BN in cash after interest & maintenance capex less the $1.37BN for new projects). Distributions to the owner would be growing at 4.8% annually. This comes from taking the $329MM generated by new projects, multiplied by an 80% payout ratio, since we’re assuming 20% of cashflow gets reinvested back in the business ($329 times 80% divided by $5.47BN = 4.8% growth rate).

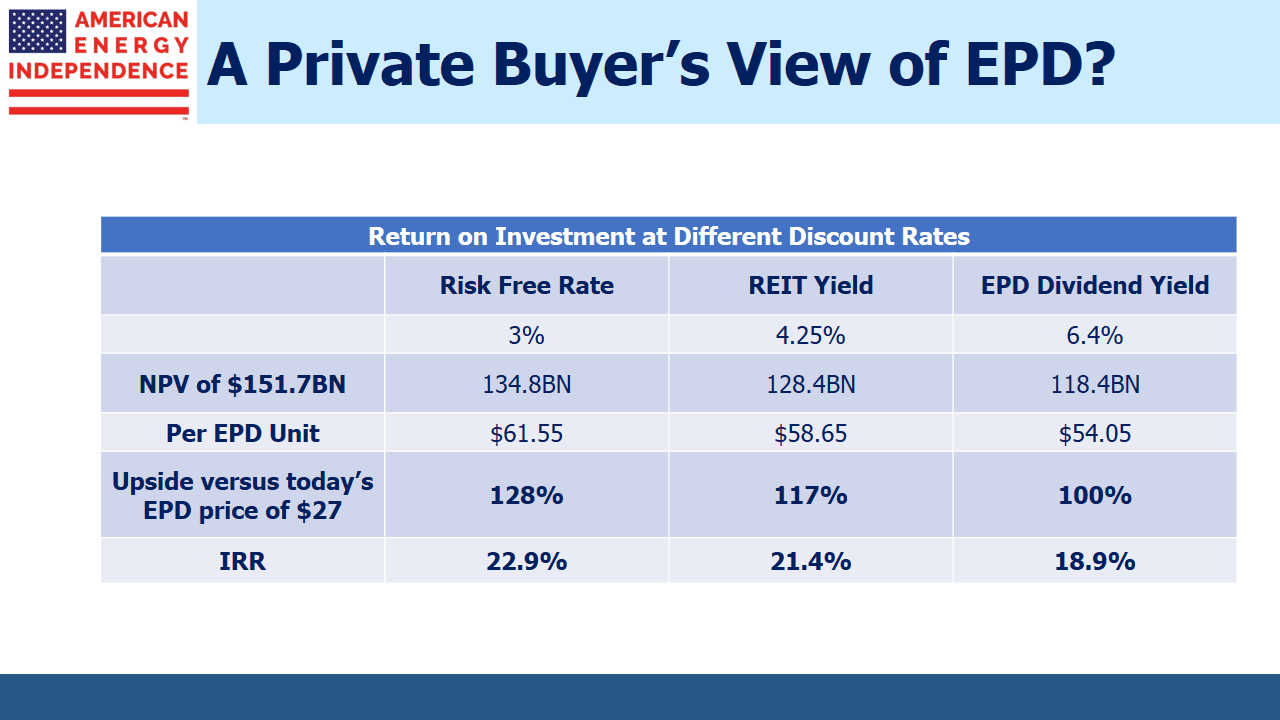

By comparison, Utilities have a dividend yield 3.5% and REITs 4.25%, both with similar growth rates. If EPD was simply valued at the same yield as REITs, the $5.47BN in 2022 cash flow would be worth $128.7BN. Add back the $23B in cash received to that point gets to $151.7BN. Discounted back to today at the risk free rate of 3%, gives a market value of $134.8BN. Divide by EPD’s current share count of 2.19BN units gives a price of above $60/unit, more than double today’s unit price.

Cash flow analysis presents a very different picture of MLP valuation than looking at conventional multiples such as P/E or EV/EBITDA.

The problem for public market investors is that EPD units come with a K-1. This generally rules out tax-exempt and foreign institutions, as well as non-U.S. individuals. The remaining investor base is narrow, consisting of older, wealthy Americans who want stable income. This group is still smarting from the 34% drop in MLP payouts, as reflected in AMLP. The MLP model may not be broken, but the trust of many of the traditional MLP investors is, which in effect means the same thing.

Cash flow analysis is how private equity buyers tend to value companies, although EPD is probably too big for such a take-private transaction. This illustrates why private equity firms often outbid the large midstream public companies for assets, despite the latter’s enormous competitive advantages of linking to existing integrated systems, and the associated synergies of maximizing utilization across their assets.

We are invested in EPD, KMI, MMP and OKE. We are short AMLP

What the Midterms Mean for Stocks

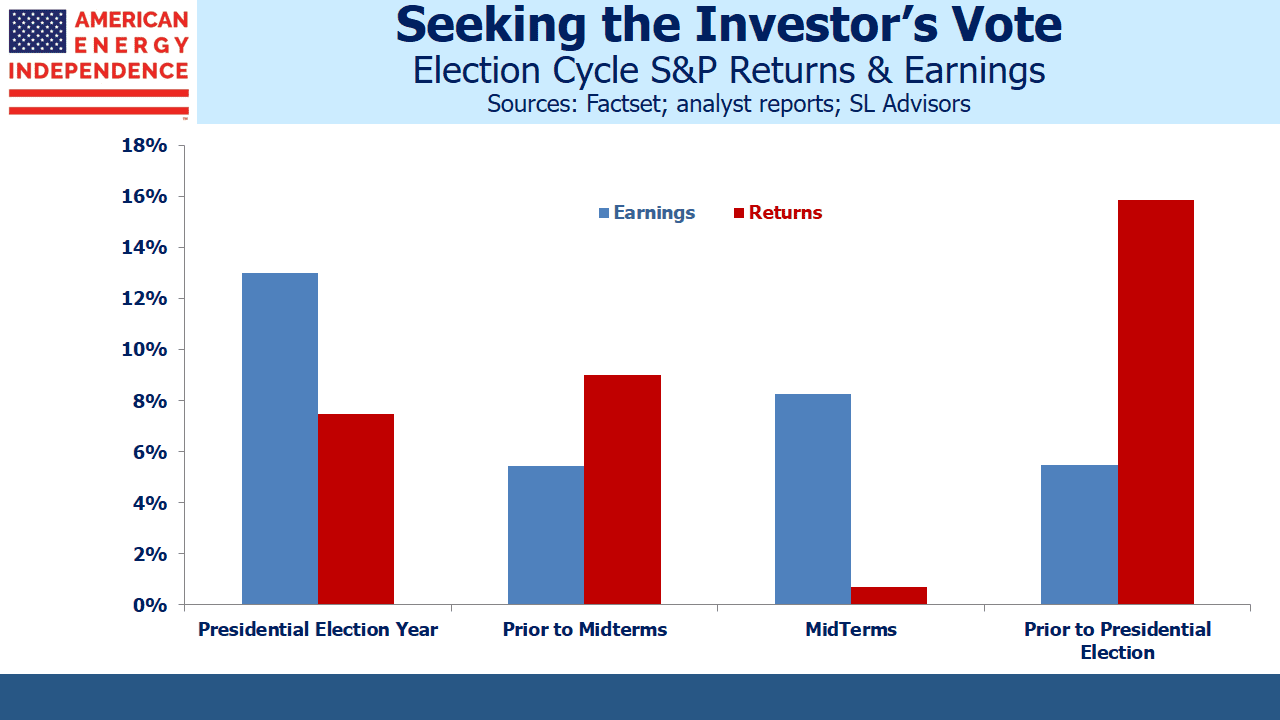

/0 Comments/in Global Issues/by Simon LackEquity returns are historically strongest in the year following the midterms. Conspiracy theorists will judge that politicians in office focus on market-friendly moves that aren’t limited to government spending in order to stay in power. Whatever the reason, the effect is quite remarkable. Since 1960, the S&P500 has risen by 15.9% on average in the third year of a Presidential cycle, almost twice the 8% average across all years.

When equity returns in the year following midterms have been poor, the White House has often changed hands. In 2015 stocks were flat and Trump’s victory followed. Eight years earlier, modest losses in 2007 provided Obama with his opening, and the 2008 financial crisis confirmed the pattern.

Many people feel that a divided government is preferable since it requires both parties to compromise in order to achieve anything. With the House of Representatives shifting to Democrat control, legislation will require support from both parties. However, the numbers don’t support this, with such returns in the year following midterms 1% lower if one of the two houses of Congress is controlled by the party not in the White House.

So history suggests 2019 should be a good year for stocks.

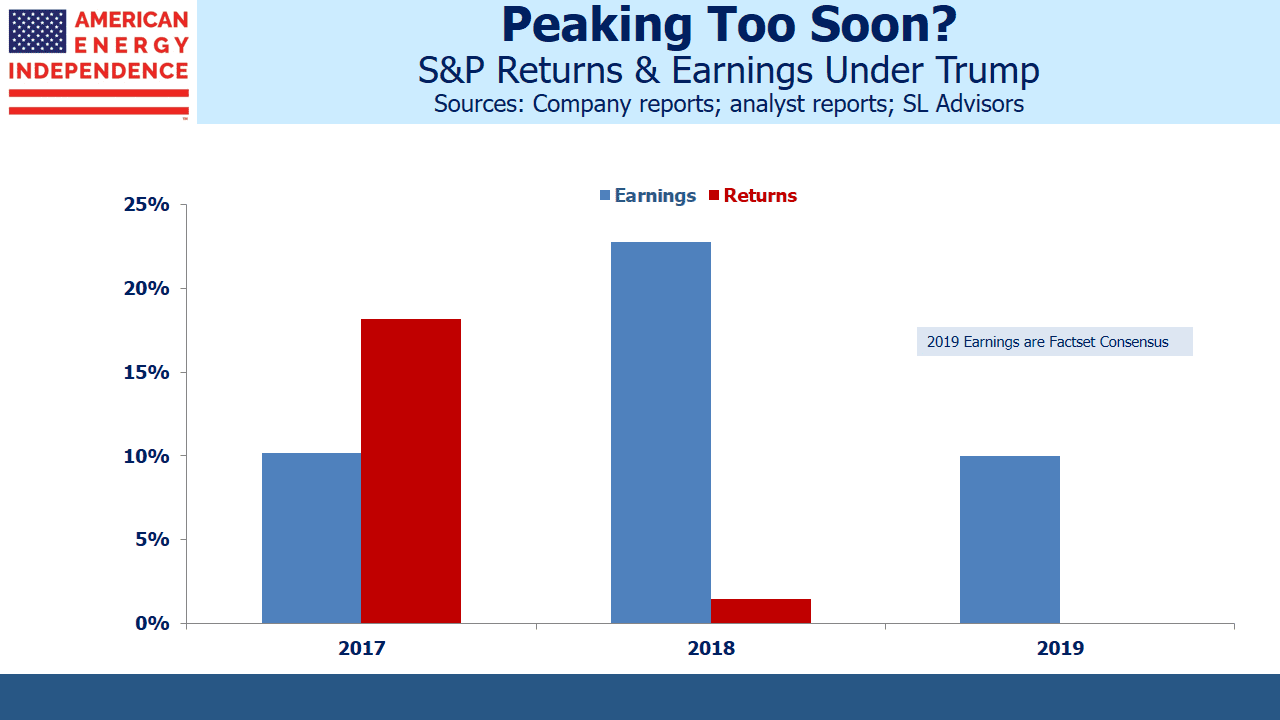

But much about the Trump presidency is different. Looking at S&P500 earnings by year presents a different picture. Earnings growth in a midterm year is 8.3%, approximately the average. Earnings tend to be strongest in Presidential election years. That’s partly what drives good returns following midterms, because investors look ahead to stronger profits the following year.

2018 S&P earnings are coming in at +22%, fueled by the cut in corporate taxes. That’s likely to be the strongest profits year of the four year cycle, and it’s come two years ahead of what typically happens.

So it’s possible the election cycle effect may have already peaked; last year’s 18% rise in the S&P500 was looking ahead to this year’s jump in earnings. The new administration completed tax reform following its first full year in office.

Factset is forecasting 10% earnings growth for 2019 – still higher than the 50+ year average albeit down sharply from this year.

In addition to the votes for elective office, many states included ballot questions for voters to consider.

Colorado included a proposal (Proposition 112) that would mandate a 2,500 foot setback for oil and gas development (including gathering & processing plants and pipelines) from “vulnerable” areas (residential neighborhoods, schools, parks, sports fields, general public open space, lakes, rivers, creeks, intermittent streams or any vulnerable area). Analysis showed that it would essentially ban oil & gas development on non-federal lands. It was a keenly contested issue, with one side claiming that energy extraction is endangering air quality while the other noted the jobs at risk from such a move.

Voters rejected it 57 to 43, which is a relief for Colorado’s oil and gas industry. Strikingly, Weld County, home to most of Colorado’s drilling, voted against 112 by a resounding 75/25. If the people closest to it are so strongly in favor of its continuation, it’s not clear why a statewide ballot was the right approach.

Proposition 112 was in any case likely unconstitutional, since leaseholders losing their property (i.e. their foregone right to drill for oil and gas in affected areas) would have sued the government for compensation. It illustrates why direct democracy is such a clumsy instrument, since “yes/no” public questions aren’t easily translated into coherent legislation. Politicians in the state had previously failed to act, which created enough public support to get the question on the ballot.

Even though Proposition 112 lost, it reflects the ambivalence of many regions over the development of America’s hydrocarbon reserves. The energy sector spent money on commercials highlighting the threat to the local economy, given 112’s stifling provisions. Colorado’s legislature is now likely to take up the issue and pass legislation intended to address the concerns of the proposals supporters. It means existing energy infrastructure already in service has a little more value, given increasing challenges to development.

Magellan Midstream: Keeping Promises But Still Dragged Down by Peers

/1 Comment/in Midstream Energy Infrastructure/by Simon LackMany MLP management teams have pursued growth at the expense of honoring their promise of stable distributions. We think the sector’s persistently high yields need explaining. Last week’s blog post (Kinder Morgan: Still Paying for Broken Promises) drew thousands of pageviews and over a hundred comments on Seeking Alpha.

Although Kinder Morgan (KMI) got there through a series of steps, ultimately they redirected cashflows from distributions to new projects. From an NPV standpoint, financial theory holds that investors should be indifferent to how a company deploys its cash as they can always manufacture their own dividends by selling some shares.

Markets don’t work that way. Capital investments are not an expense, they’re a use of cash. But the dividend cuts required to fund them were treated as a drop in operating profit by investors. KMI should have understood this, because for many years prior to 2014 they sought investors who valued stable dividends. KMI then decided they no longer wished to appeal to those investors, and their valuation still reflects the betrayal. The bitterness of many investors is on full display via the comments on last Sunday’s blog.

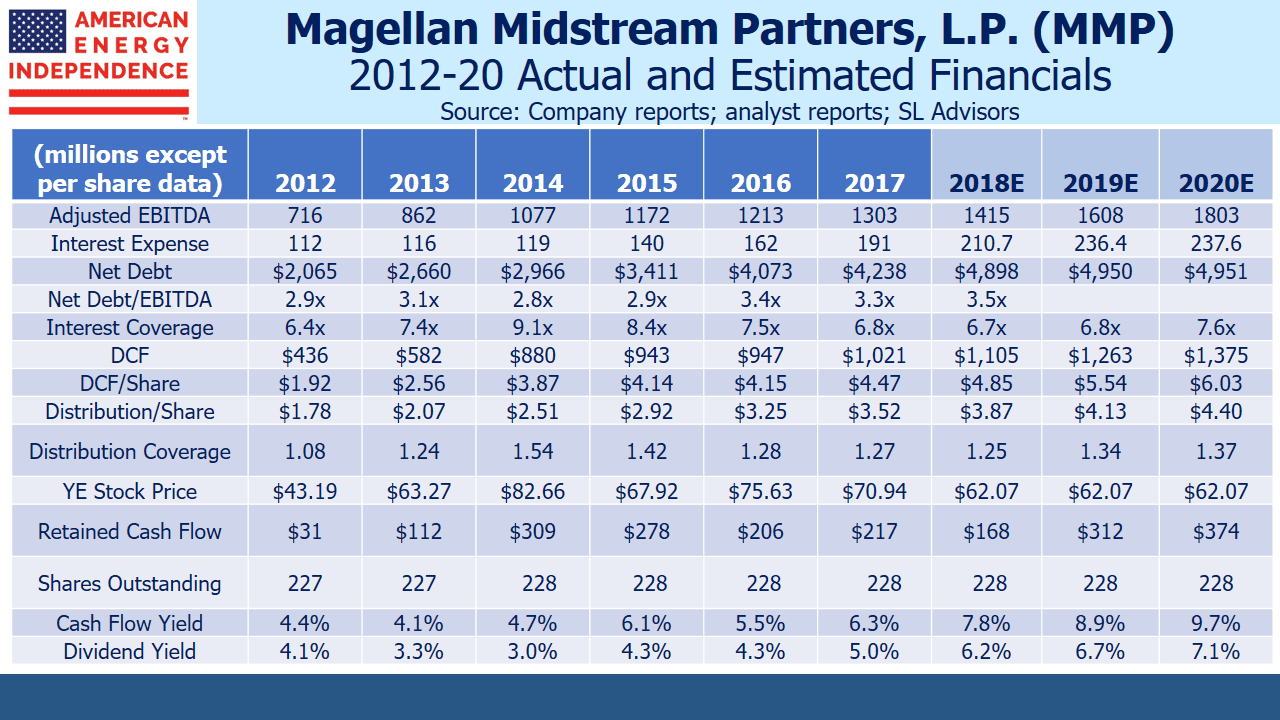

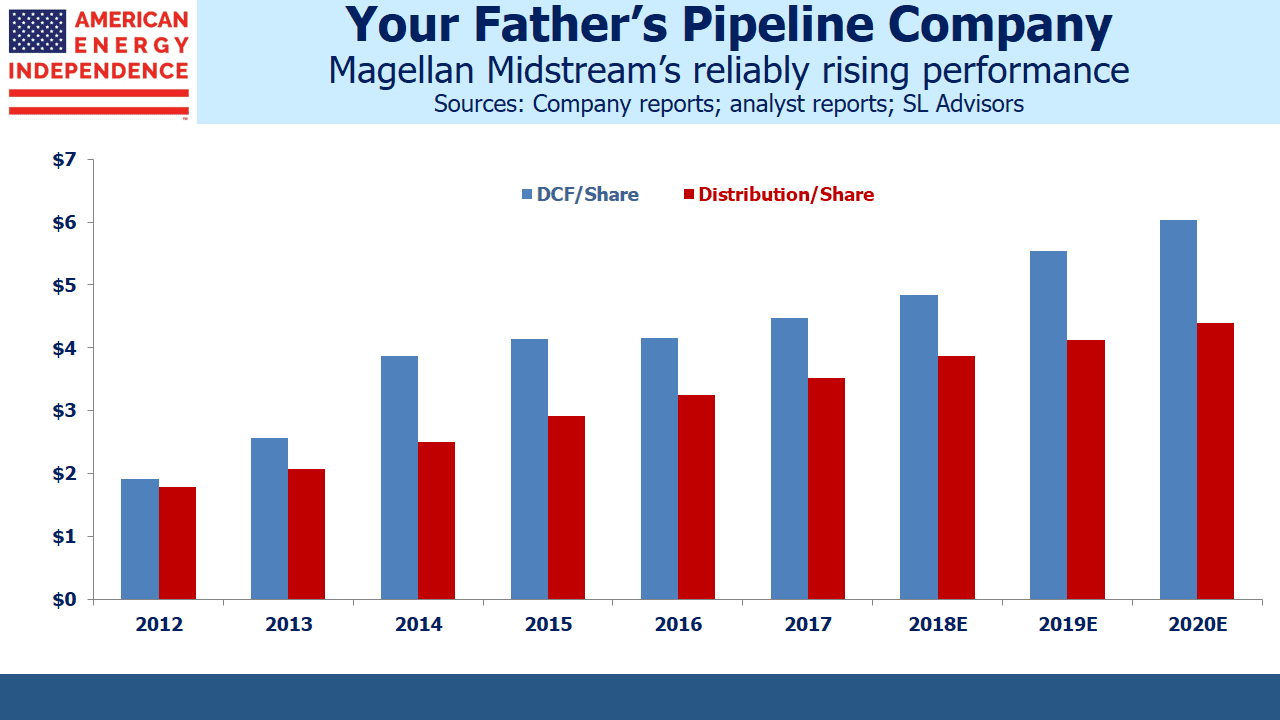

KMI’s problem of an undervalued stock is self-inflicted – but what about other MLPs who have been faithful to their income-seeking investor base? Magellan Midstream (MMP) does all the right things:

- Grows Distributable Cash Flow (DCF) annually

- Raises its dividend (distribution), annually

- Finances its growth projects with internally generated cash, thereby avoiding dilutive secondary offerings of equity

- Maintains a strong balance sheet with Debt:EBITDA consistently below 4X

Such judicious capital management has probably caused MMP to pass on growth opportunities that others have chosen. Energy infrastructure analysts widely hold that the sector remain undervalued. Dozens of MLP distribution cuts are at least part of the reason – so a company that has remained steadfast should stand out.

But while MMP’s unwavering embrace of its principles has helped, it hasn’t been enough to truly separate them from their less reliable peers.

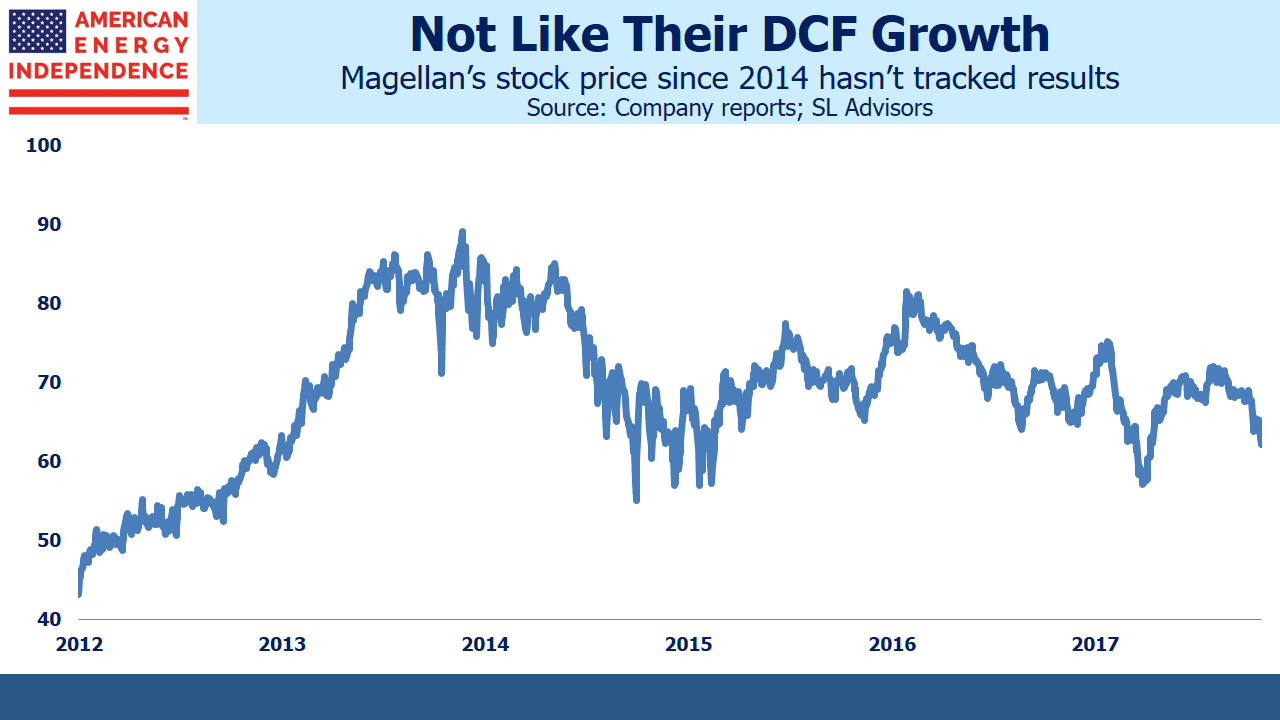

MLPs peaked in 2014. Since then, MMP has raised per unit EBITDA by 31%, per unit DCF by 25% and distributions are up 54%. Distribution coverage remains healthy at 1.25X.

MMP’s leverage has risen, from 2.8X to 3.5X, but will drop back next year as new projects come into production. Even at 3.5X it is comfortably below the 4X that most of their peers target.

Magellan’s management team hasn’t issued equity or made dilutive acquisitions. They’ve done just what they promised by increasing cash flows & distributions while maintaining a strong balance sheet. And yet, MMP’s stock price is 26% below where it ended 2014.

MMP’s yield is more than 2% below the AMZ, reflecting a valuation premium relative to the MLP index. But the entire sector is laboring under the history of dozens of distribution cuts, which have lowered the payout on the Alerian MLP ETF by 30%. MMP’s valuation has moved in the opposite direction from its steadily improving operating performance in recent years, reflecting that traditional MLP investors remain far less enthusiastic than in the past.

The most common question asked of investors is, given persistent undervaluation, what is the catalyst that will drive prices higher? We showed last week that an MLP’s DCF yield is analogous to the Funds From Operations measure used in real estate, since it represents cashflow generated after the cost of maintaining the assets but before investment in new projects. On that basis, MMP’s 9.1% DCF yield (based on $5.54 per unit for 2019) is pretty attractive for a long term holder.

However, many investors prefer immediately rising prices following a purchase to confirm their buy decision. Continued strong earnings should support increases in payouts. 3Q18 results for pipeline companies have been strong. Current forecasts are for 5-6% annual distribution growth for MLPs – slower than their growth in DCF as they build coverage for their distributions. Since many MLP managements continue to believe their stock undervalued, they prefer internally generated cash to issuing expensive equity. We agree. We expect dividend growth for the broad American Energy Independence Index (80% corporations and 20% MLPs) of 10% next year.

Rising dividends should improve sentiment.

We are long MMP and KMI.

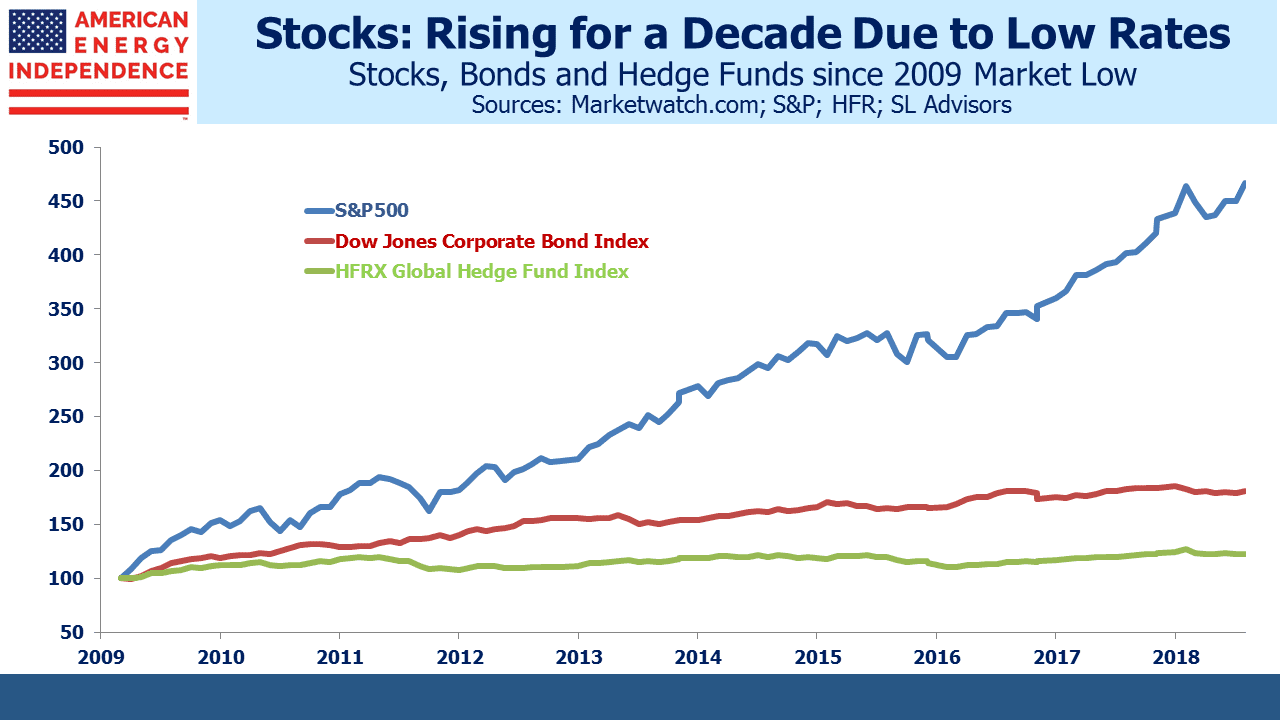

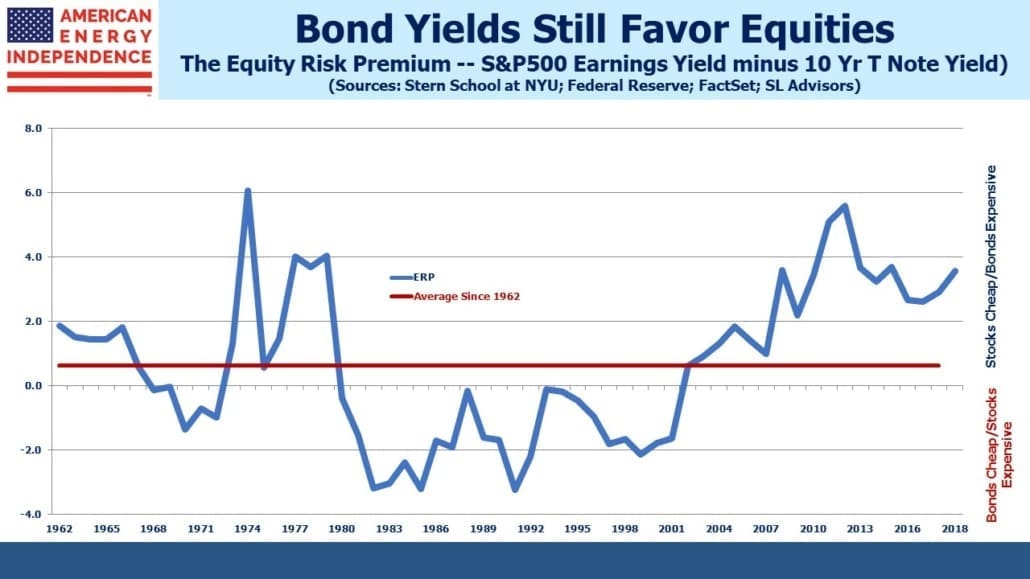

Bonds Still Can’t Compete with Stocks

/0 Comments/in Bonds Are Not Forever/by Simon LackThe Equity Risk Premium (ERP) is a handy way to compare valuations of equity with fixed income. It compares bond yields with the earnings yield on stocks (the earnings yield is reciprocal of the price/earnings ratio). Six years ago, when the Fed was well into quantitative easing and bond buying, it gave a clear signal that stocks were a far better long term investment than bonds. The yield on ten year treasuries was below 2%. Government policy was to create a huge disincentive for investors to hold fixed income through unattractively low rates, and it worked. Holding risky assets such as equities has substantially outperformed less risky bonds.

It’s not only relative valuations that supported stocks, but earnings growth. 2018 earnings on the S&P500 are coming in 22% higher than 2017. Pessimists will note that this growth won’t be sustained into next year, but the FactSet consensus estimate for 2019 is still 10% growth, which isn’t bad.

So what is the ERP telling us now? In 2012 the difference between yield on S&P500 earnings and ten year treasuries reached 5.6%, the widest since the 1970s and fully 5% above the 50+ year average. Interest rates were artificially low, and had they risen rapidly, the relative attraction of stocks would have quickly receded. But there were good reasons to expect low interest rates to persist, as I wrote in Bonds Are Not Forever; The Crisis Facing Fixed Income Investors. A financial crisis caused by too much debt required low rates to ease the deleveraging. Although bond yields have been rising, they’re still not historically high. The long term real return on ten year treasury notes is 2%. That suggests 4% is a neutral yield (2% historic real return plus 2% projected inflation). At a little over 3%, rates are still well short of neutral. It would take a jump of at least 2% in bond yields before they’d look historically attractive.

Although Trump is so far associated with a strong stock market, October’s rout has pretty much wiped out any positive return for the year. As Stephen Gandel pointed out in Bloomberg last week, on a valuation basis equities are now lower than they were before the 2016 election. In other words, earnings growth has outpaced the market.

Moderately rising bond yields combined with strong earnings growth that hasn’t flowed through to prices means that stocks look attractive. Today’s ERP of 2.9% isn’t as compelling as in 2012, but it’s wider than the prior couple of years. Moreover, next year it’ll widen to 3.6% because of earnings growth, the third best level in the past decade. Relative valuations can withstand a continued gentle move higher in interest rates.

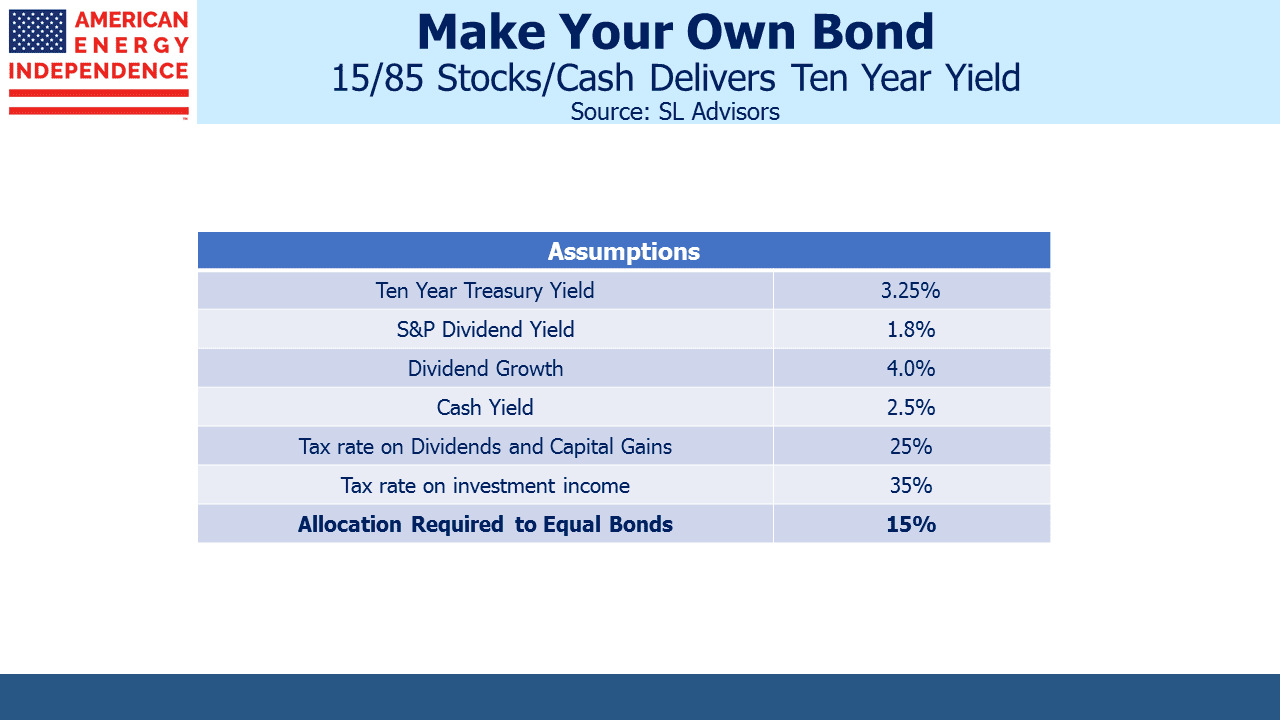

An interesting way to compare stocks and bonds is to calculate how much of $100 you’d need to hold in equities, with the balance in cash (six month treasury bills, which yield around 2.5%), in order to replicate the return from holding ten year treasuries. It relies on some simplifying assumptions: that the current yield on the S&P500 persists, that tax rates won’t change, and an estimate for dividend growth (we used 4%). Keeping the dividend yield unchanged means stocks would appreciate at the same rate as dividends.

We’ve used this analogy for many years – see The Sorry Math of Bonds from October 2011. Back then, bond yields were 2% and we showed that a portfolio invested 20/80 between stocks and cash had a good chance of matching an investment in bonds. What was striking about that analysis was it assumed the 80% in cash earned nothing for the full ten years. Although short term rates were 0% back then, they were likely to rise over the following decade as they clearly have. That 20/80 allocation has worked very well.

Today’s S&P yield is 1.8%, ten year yields are around 3%, and cash pays 2.5%. We’ll retain the 4% dividend growth rate we assumed before, although that’s probably conservative. The trailing growth rate is 8.65%.

The net result is that a 15/85 split between stocks and cash delivers the same return as 100% in bonds. In other words, stocks are relatively an even better bet.

This might seem surprising since bond yields have risen so as to be more competitive, and the dividend yield on stocks is lower. The big difference comes from cash rates, which are currently 2.5%. Cash is no longer trash, so it contributes to the return, whereas in our 2011 example it didn’t. And bond yields still aren’t that high. You pick up less than 0.75% by moving from short term to ten years, not much additional return for the risk.

It works because dividend growth is a powerful driver of returns. The static return on bonds is no match over the long run for rising S&P500 earnings which support dividend hikes. The tax code also favors dividends and capital gains over the ordinary income of bonds. Put another way, since the yield curve only offers 0.75% to move out on the curve, you don’t need much in a risky asset to generate that additional return.

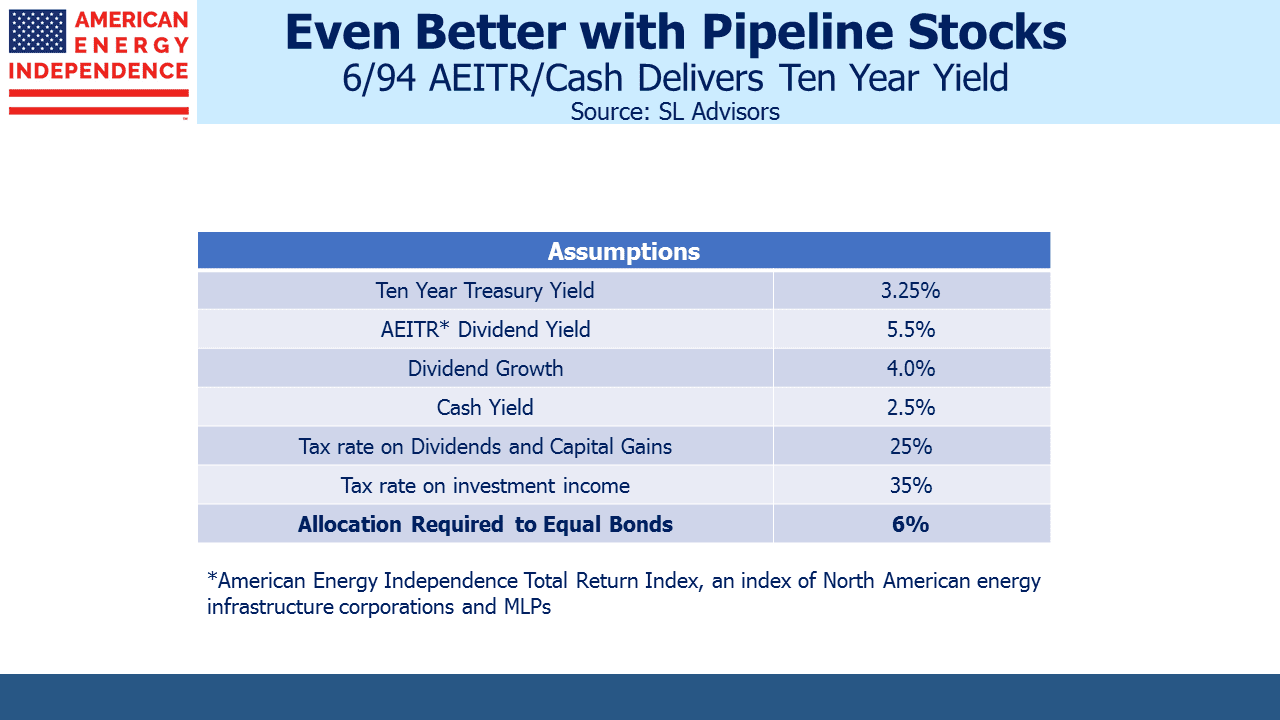

Because we invest in energy infrastructure, we’ve also run the Math assuming you use the American Energy Independence Index (AEITR), yielding around 5%, instead of the S&P500. This is an index of the biggest North American pipeline companies, mostly corporations with 20% MLPs.

We expect 10% annual dividend growth on our index over the next couple of years, but conservatively assuming the same 4% as with the S&P500, a 6/94 split between AEITR and Cash would match bonds. Dividends are important, and because pipeline stocks yield more than bonds, the Math works powerfully.

The Equity Risk Premium shows that stocks are cheap. But if recent market volatility makes you want to move to fixed income, you can synthetically create your own bond with the 15/85 portfolio. For even the most bearish investor, the case for holding some equities remains a powerful one for the long term.

Kinder Morgan: Still Paying for Broken Promises

/1 Comment/in Midstream Energy Infrastructure/by Simon LackBroken promises aren’t quickly forgotten. That’s the hard lesson being learned by pipeline company managements, as the sector remains cheap yet out of favor.

Kinder Morgan (KMI) reported good earnings on October 17th. Volumes were up, and they sold their Trans Mountain Pipeline (TMX), including its expansion project, to the Canadian Federal government. TMX is Canada’s only domestic pipeline that can supply seaborne tankers. All other pipelines lead to the U.S.

Canada’s landlocked energy resources are becoming a political football. Alberta wants to get its oil and gas to export markets, but neighboring British Columbia opposes the new pipelines necessary for Albertan crude to reach the Pacific coast. Caught between the two provinces, KMI sensibly sought an exit. The transaction was well timed, closing before cost estimates for completing the expansion were ratcheted up and a court ruled that a new environmental study was required (see Canada’s Failing Energy Strategy). Canada’s taxpayers were on the wrong end of the deal.

Nonetheless, Rich Kinder opened the earnings call lamenting KMI’s valuation. He said, “I’m puzzled and frustrated that our stock price does not reflect our progress and future outlook.” We do think KMI is cheap, but the explanation lies in recent history. Before the Shale Revolution created the need for substantial new pipeline investments, KMI’s investor presentation reminded “Promises Made, Promises Kept.”

This turned out to be true only until financing new projects conflicted with paying out almost all available operating cash flow in distributions. Investors in Kinder Morgan Partners (KMP), the original vehicle, were heavily abused. They suffered two distribution cuts and a realization of prior tax deferrals timed to suit KMI, not them (see What Kinder Morgan Tells Us About MLPs). Former KMP investors, who are numerous, retain deeply bitter memories of the events and have lost all trust in Rich Kinder.

KMI was only the first of many. Distributions on Alerian’s MLP index have been falling for three years. Their eponymous ETF has cut its payout by 30%. Alerian CEO Kenny Feng, normally a reliable cheerleader for the MLP model, recently turned more critical, citing,”…significant abuses of [distribution growth] in the past…” The irony is that until late last year Alerian’s own website showed reliable distribution growth, completely at odds with what investors in their products were experiencing. They only corrected it when mounting criticism from this blog (see MLP Distributions Through the Looking Glass), @MLPGuy and others forced a humbling revision.

Too few commentators acknowledge the poor treatment of MLP investors (see MLP Investors: The Great Betrayal). Pipeline stocks are attractively valued but have been that way for some time. The legacy of broken distribution promises continues to cast a pall. KMI’s objective in abandoning the MLP model was to be accessible to a far broader set of investors as a corporation. So far, it hasn’t helped their stock price.

One explanation might lie in how they present their financial results. Distributable Cash Flow (DCF) is a term widely used by MLPs and retained by KMI even after it became a corporation. MLPs calculate their distribution coverage ratio, which is the amount by which DCF exceeds distributions. It’s somewhat analogous to a dividend payout ratio, albeit based on DCF not earnings. Kenny Feng notes that generalist investors aren’t familiar with DCF or its coverage ratio. It may be why KMI’s stock is languishing.

DCF is Free Cash Flow (FCF) before growth capex. MLPs have long separated capex into (1) maintenance, required to maintain their existing infrastructure, and (2) growth, for new projects. FCF, a GAAP term, is indifferent to the two types of capex and deducts them both. DCF (not a GAAP term) treats them differently by excluding growth capex, and is always higher.

Unsurprisingly, KMI regularly promotes its 11% DCF yield, which is higher than its energy infrastructure peer group. However, FCF is the more familiar metric, and is lowered by the subtraction of growth capex. Because KMI spent over 70% of its $4.5BN DCF on new projects, the remaining $1.4BN in FCF results in just a 3.3% FCF yield. This is still higher than the energy sector and certainly better than utilities (which are often negative because of their ongoing capex requirements). But it doesn’t stand out versus other sectors, and probably causes analysts to overlook the high DCF yield.

As a corporation, KMI continues to promote a DCF valuation metric used by MLPs, Using the more common FCF yield, it isn’t compelling. However, DCF seems reasonable to us given their business model.

To see why, consider yourself owning an office building. After all cash expenses, including maintenance and setting aside money annually to replace HVAC and other equipment, it generates $1 million in cash, annually. In real estate this is called Funds From Operations (FFO). Because you’re already deducting the expenses required to keep the building operating, and it’s most likely appreciating in value, it’s reasonable to value it based on the $1million recurring cashflow. A cap rate of 5% means you’d require at least $20 million before agreeing to sell it.

Now suppose you decided to redirect $700K of your $1 million annual cashflow towards buying a second building that you also plan to rent out. You still own a $20 million asset, and reinvesting some of that annual cashflow in a new building doesn’t affect the value of what you already own.

In this example the $1million in FFO is analogous to KMI’s DCF. It’s why they believe their stock is undervalued, because 11% is a high DCF yield. Their FCF is so much lower because they’re investing most of their DCF in new assets that will generate a return.

GAAP FCF doesn’t differentiate between capex to maintain an asset and capex to acquire a new one, which is why pipeline companies don’t dwell much on FCF. Moreover, properly maintained pipeline assets generally appreciate. As climate activists slow new pipeline construction in some states, it simply raises the value of nearby infrastructure that can serve the same need.

Critics may believe that DCF doesn’t reflect all the necessary maintenance capex that’s really required, or that the underlying assets are depreciating in value even while properly maintained, although there’s little if any evidence to support either claim. So KMI remains misunderstood.

The dividend might offer a more compelling story. Yielding 4.7%, it’s below the 5.8% of the broad American Energy Independence Index. Because of history, investors are understandably cautious in buying for the yield. But today’s $0.80 annual payout is expected to jump to $1 next year and $1.25 in 2020. This 25% annual growth will push the yield to 7.4% in two years, assuming no upward adjustment in the stock price. A rising dividend might finally vanquish the unpleasant memories of prior cuts, and draw in new buyers.

In spite of its attractive valuation, MLP ETFs and mutual funds don’t own KMI, because it’s not an MLP, providing another good reason to seek broad energy infrastructure exposure that includes corporations.

We are long KMI and short AMLP.