Income Investors Should Return to Pipelines in 2019

MLPs have become more attractively priced compared with other income-oriented sectors. One way to see this is to compare the trailing four quarter yield. REITs and utilities have remained within a fairly narrow range, while MLPs rose sharply during the 2014-15 oil collapse. After a partial recovery, weakness over the past year or so has caused MLP yields to drift higher again.

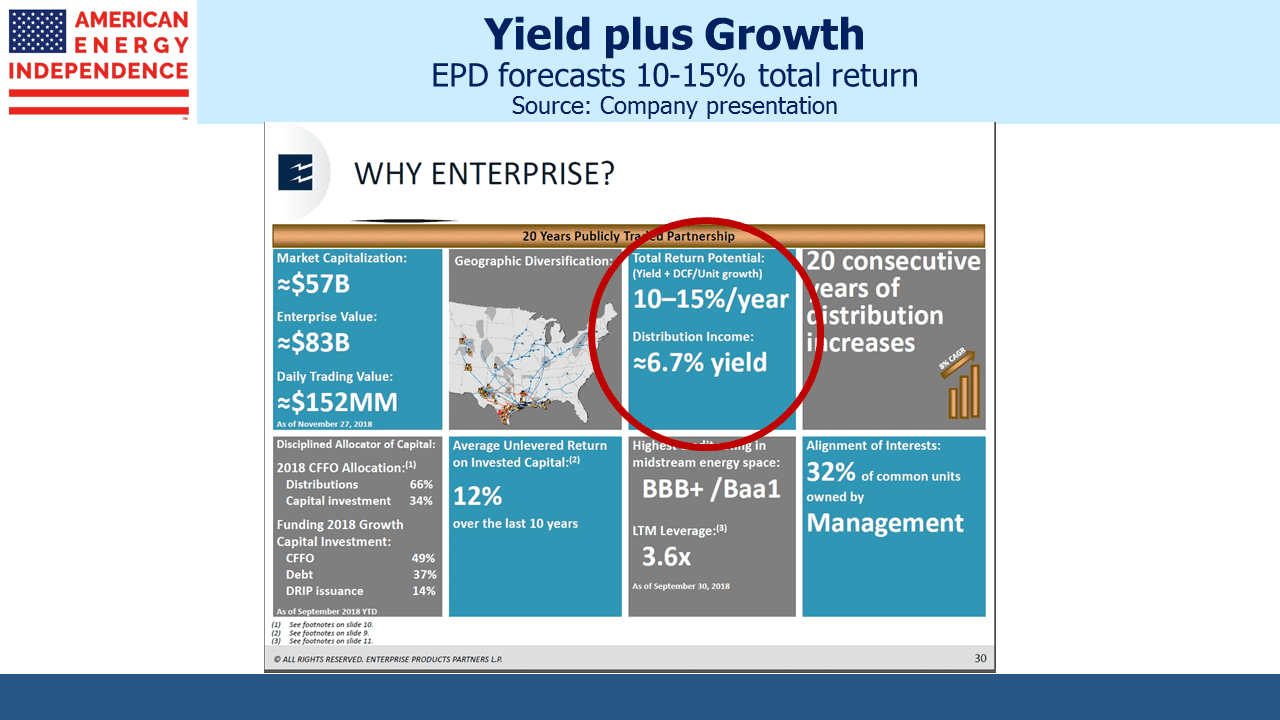

For many years prior to the 2014 sector peak, MLP yields were around 2% above utilities. Currently, they’re around 5% wider. This ought to attract crossover buying from income-seeking investors, switching their utility exposure for MLPs, but so far there’s limited evidence of this happening. Although the yield advantage over REITs isn’t quite as dramatic, the same relative value switch exists there too.

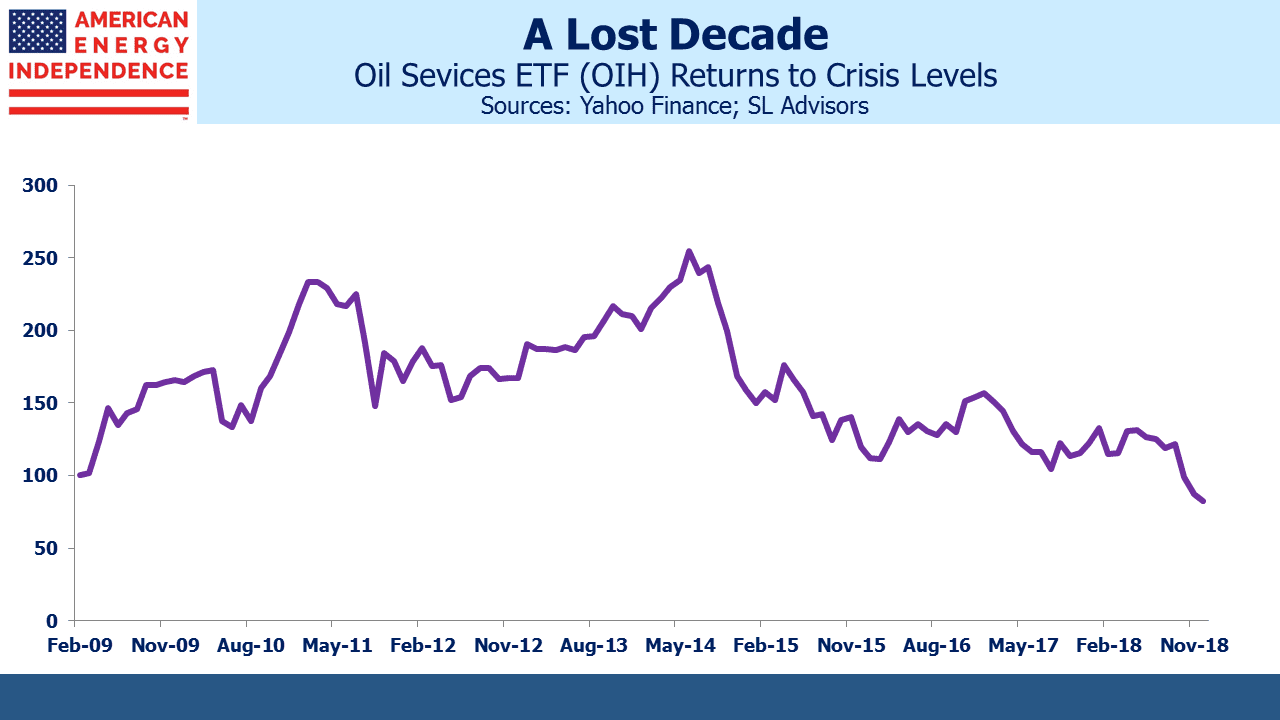

The broad energy sector has remained out of favor. MLPs used to track utilities and REITs fairly closely until 2014 when they followed energy lower. However, even compared with energy, midstream infrastructure remains historically cheap. Research from Credit Suisse shows that on an Enterprise Value/EBITDA basis, pipelines are the cheapest vs the S&P energy sector they’ve been since 2010.

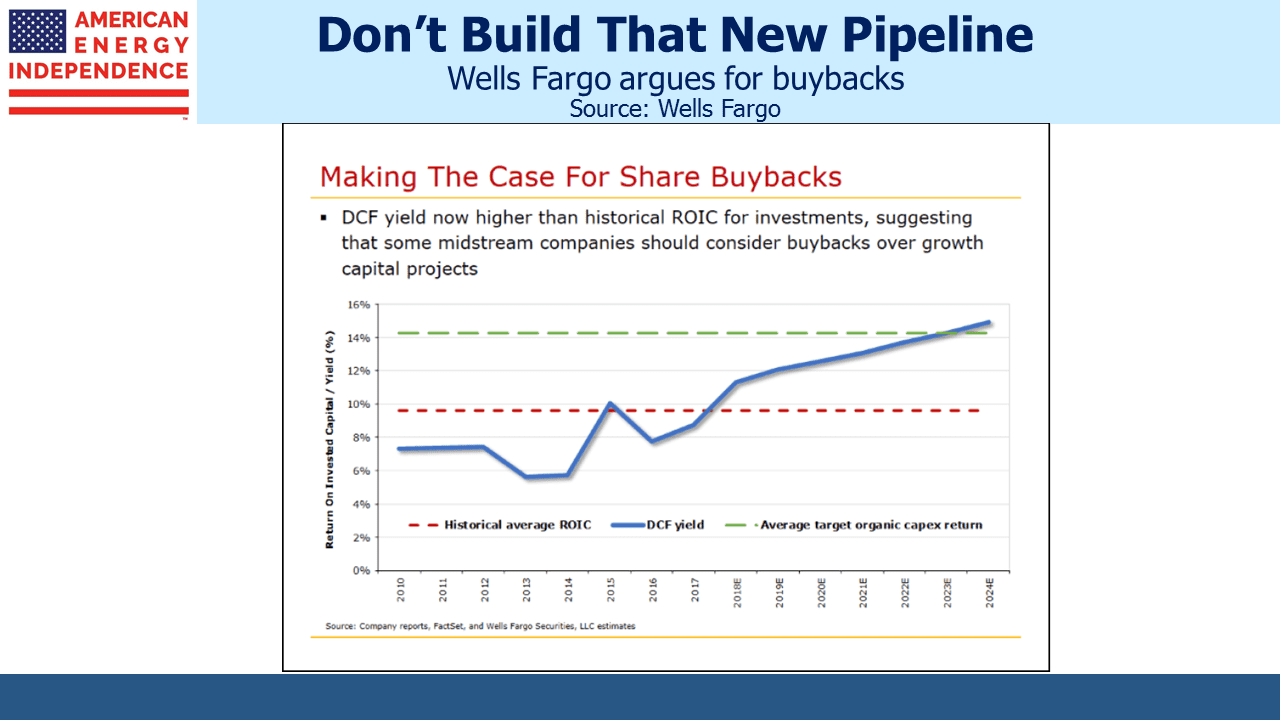

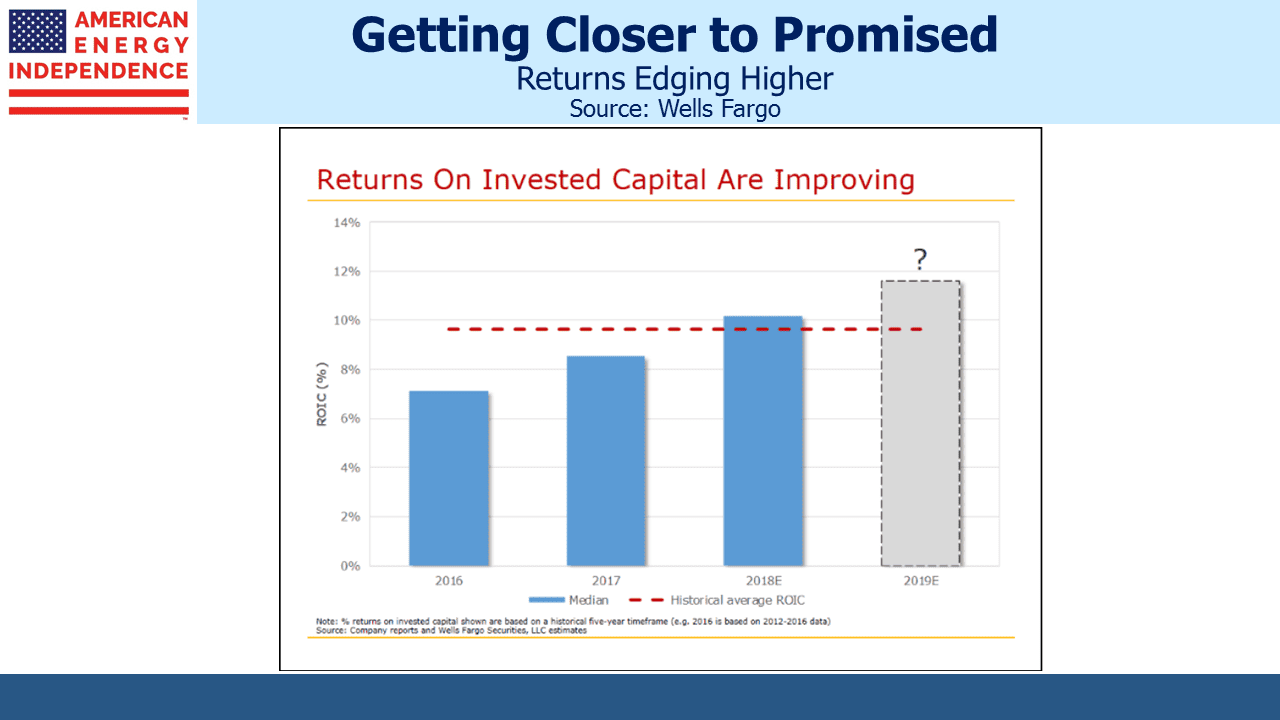

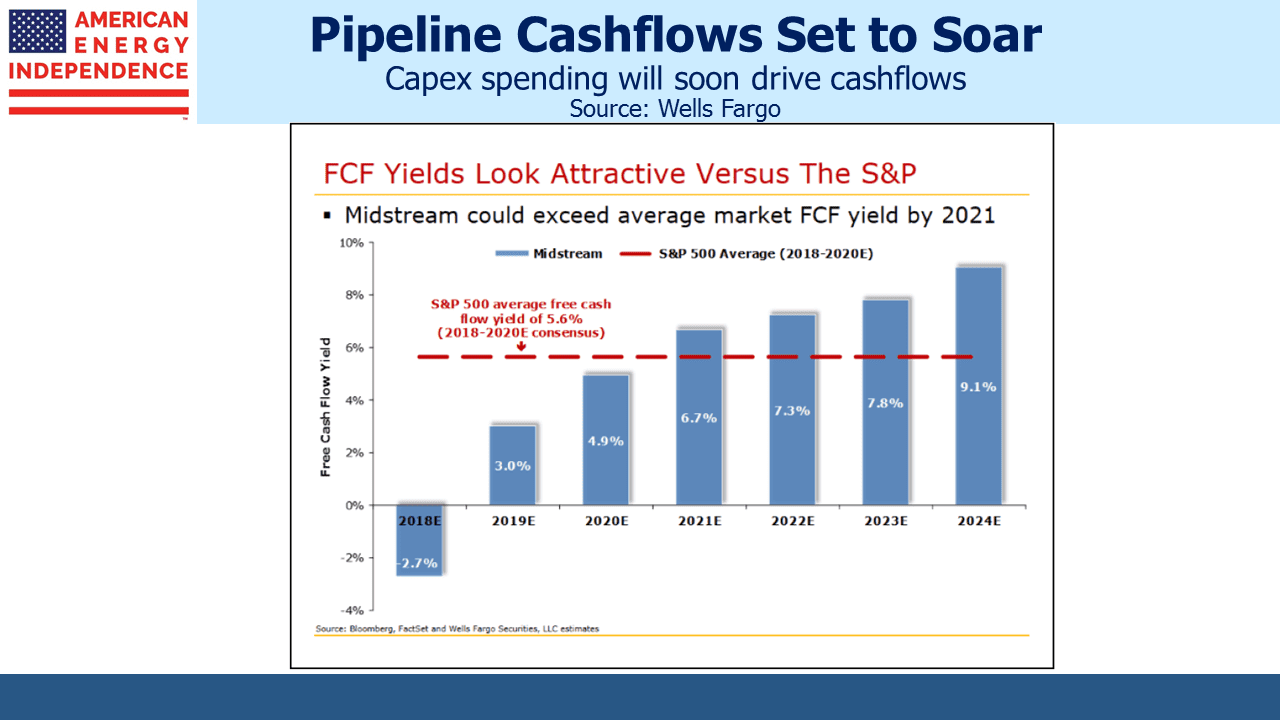

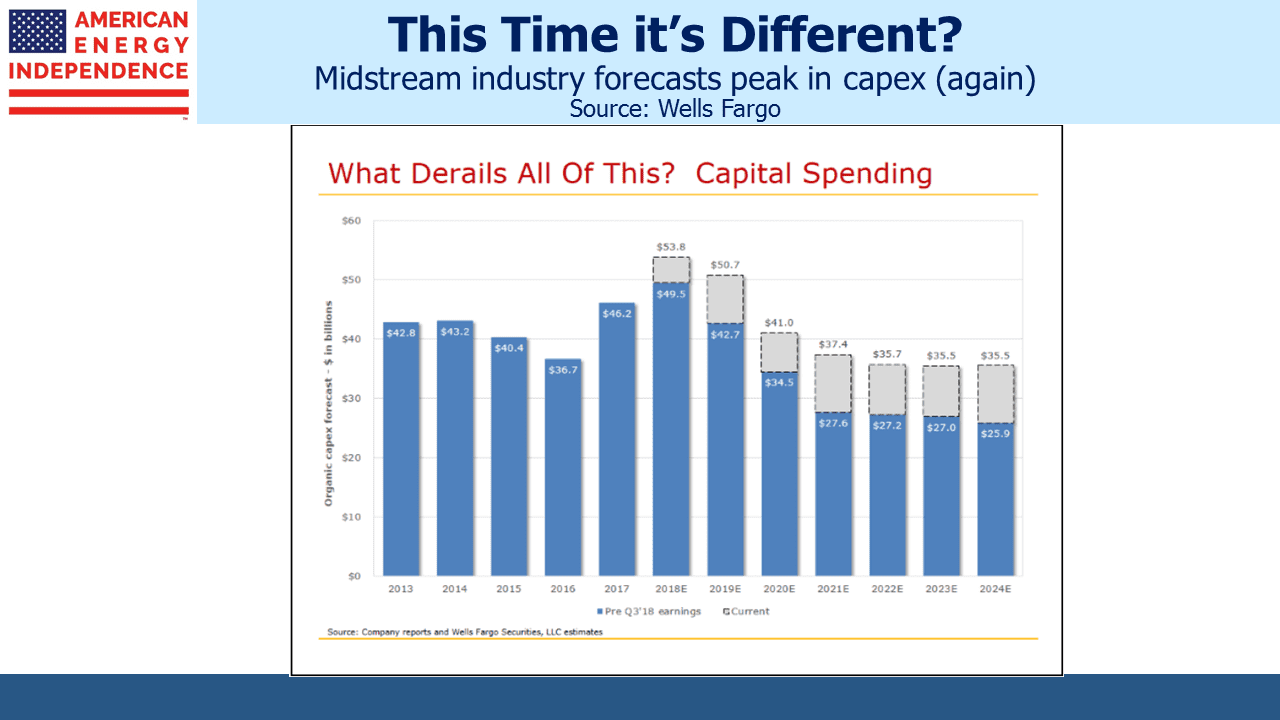

The Shale Revolution has challenged the MLP model in ways that few anticipated. Increasing U.S. output of crude oil, natural gas liquids and natural gas is creating substantial benefits for the U.S. Improved terms of trade, greater geopolitical flexibility and reduced CO2 emissions underpin America’s greater willingness to buck the global consensus. However, investors are still waiting for the financial benefits. This is partly because the capital investments required have demanded more cash. E&P companies had to fund investments in new production, which drew criticism that they were over-spending on growth. Similarly, MLPs pursued many opportunities to add infrastructure for transportation, processing and storage in support of new production. All this left less cash to be returned to investors through buybacks and dividends. It remains the biggest impediment to improved returns.

Unlike MLPs, both utilities and REITs have both been increasing dividends. Even the energy sector has raised payouts, although this was achieved in part through less spent on stock buybacks, which has led their investor base to insist on improved financial discipline. MLPs have both increased cash flows and lowered distributions. Oil & gas executives seem unable to turn down a growth project.

By contrast with the income sectors with which MLPs used to compete, they have been lowering dividends. This makes yield comparisons less reliable, and likely explains why there’s been little evidence of shifts away from lower-yielding, traditional income sectors.

It’s why the biggest pipeline companies have dropped the MLP structure in favor of becoming corporations, so as to access the broadest possible set of investors. However, that hasn’t always worked out either, as the history of prior distribution cuts continues to weigh on sentiment. Williams Companies (WMB) is an example of a corporation that combined with its MLP, Williams Partners (WPZ). WMB CEO Alan Armstrong claims to be puzzled by persistent stock weakness. Meanwhile, legacy WPZ investors well recall the multiple distribution cuts they endured along the way (see Pipeline Dividends Are Heading Up).

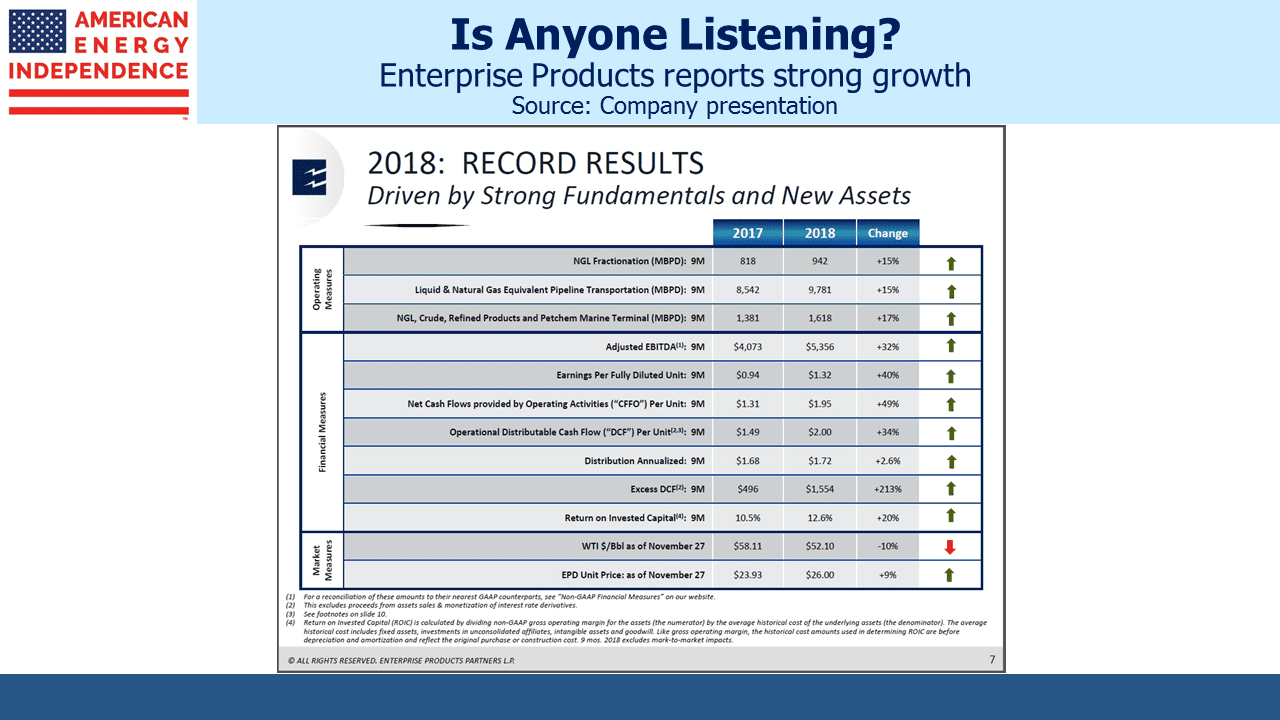

In our experience, one of the issues that makes current investors nervous and gives new ones pause is that they don’t understand the continued weakness when volumes are up and management teams bullish. In December most sectors were down sharply, and global growth concerns depressed the energy sector along with most others. But for most of 2018 and certainly the second half, the disconnect between strong operating performance and poor security returns has perplexed many.

We’ve sought to explain this, and regular readers will know we’ve concluded that reduced distributions are the most important factor. The investor base was originally drawn for stable income, which in recent years MLPs have failed to provide. The Shale Revolution, perversely, has so far been a lousy investment theme even while it’s been terrific for America. The charts in this blog post present a narrative now familiar to many.

Next year we expect rising dividends for the companies in the American Energy Independence Index to draw increasingly favorable attention to the sector. Although the MLP model no longer suits most of the biggest operators in the industry, midstream energy infrastructure offers compelling value. The best way to participate is by investing in the biggest companies, which are mostly corporations but do include a few MLPs. When the sector begins its recovery, it’ll start from far below fair value.

We are invested in WMB.

SL Advisors is the sub-advisor to the Catalyst MLP & Infrastructure Fund. To learn more about the Fund, please click here.

SL Advisors is also the advisor to an ETF (USAIETF.com).

A thoughtful essay in the Wall Street Journal (

A thoughtful essay in the Wall Street Journal (