Energy By The Numbers

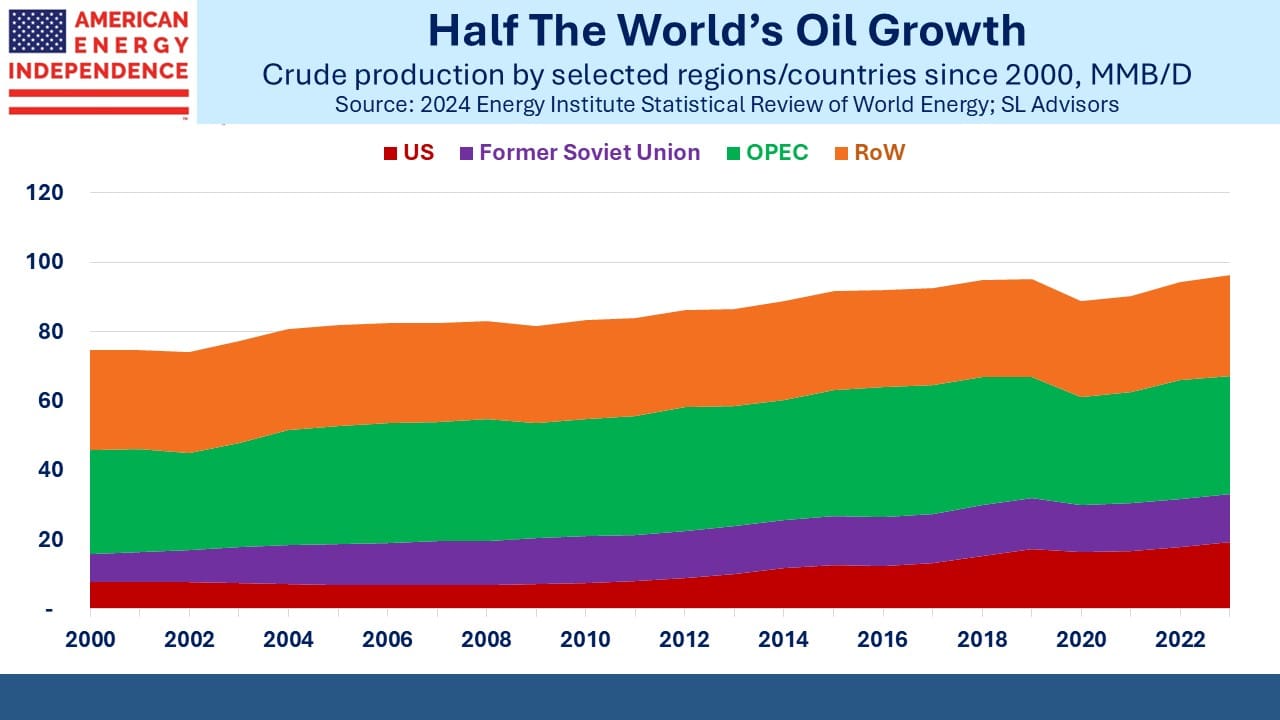

The Energy Institute’s (EI) Statistical Review of World Energy provides a wonderfully detailed view of what’s actually happening, mostly untainted by any political bias. The world is using more of all kinds of energy, raising living standards across the developing world. Hydrocarbons still dominate and will for the foreseeable future.

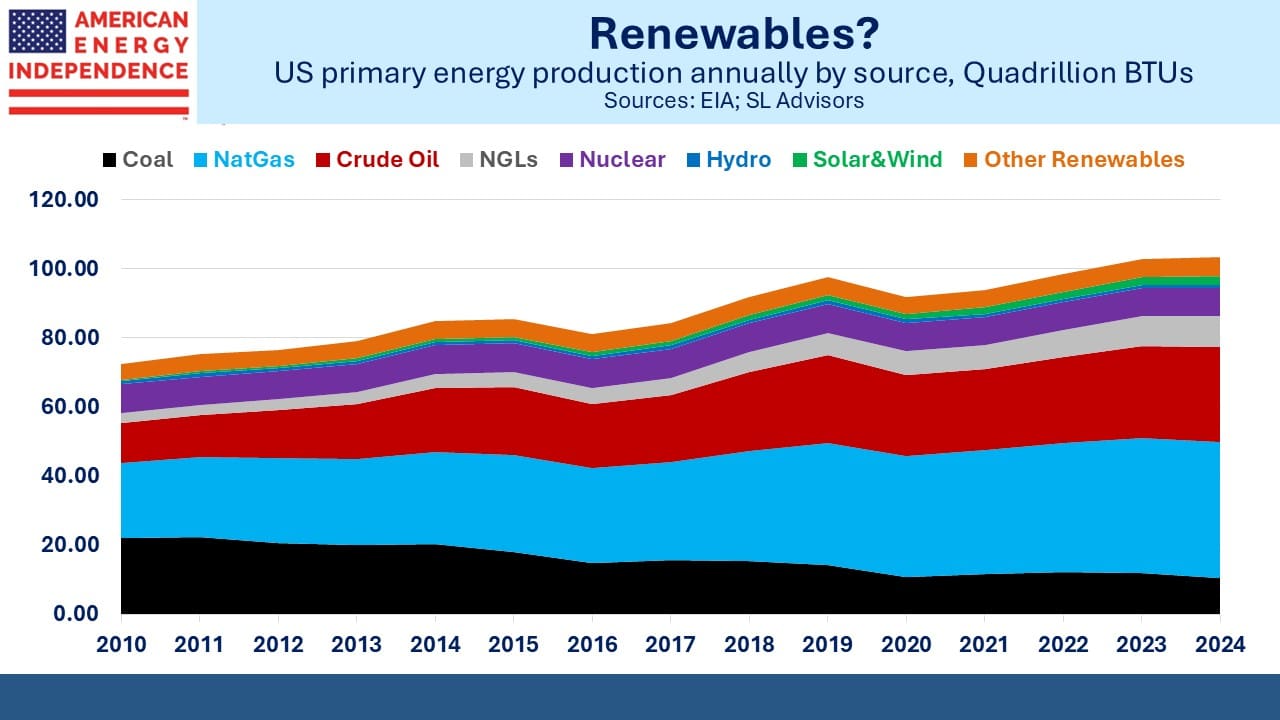

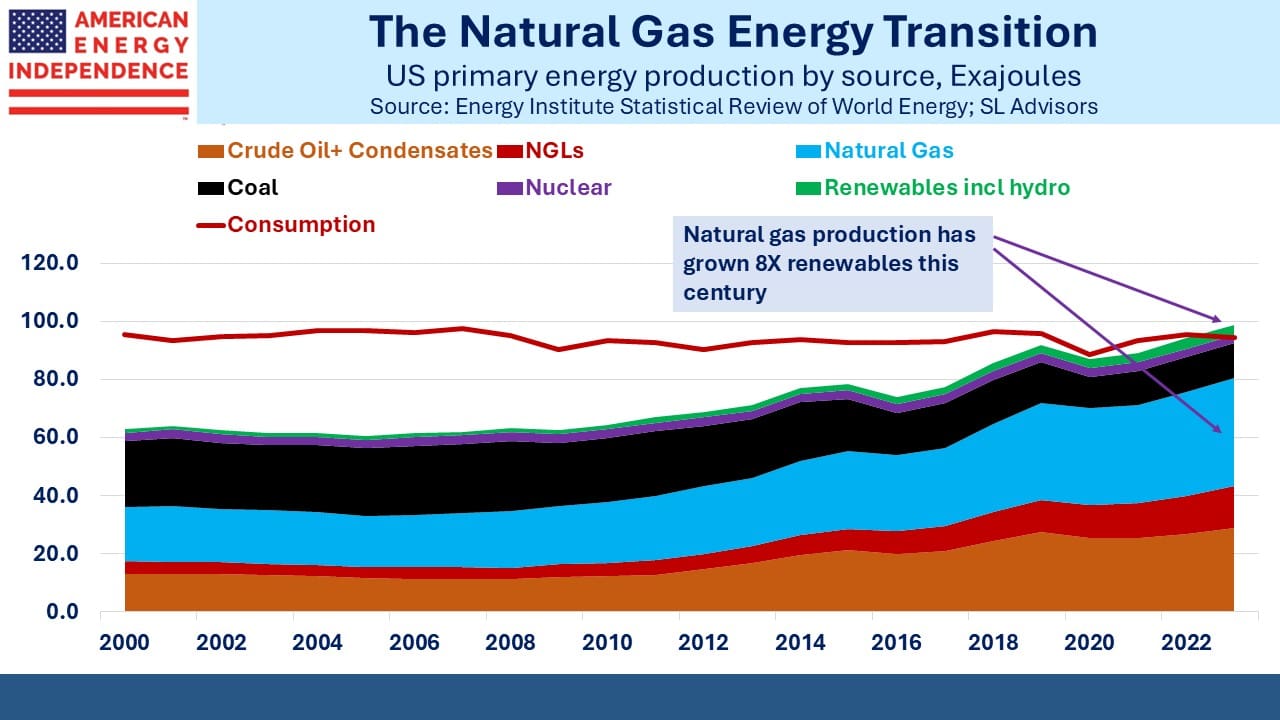

There’s still a tendency even at the EI to focus on percentage increases rather than absolute values when it comes to renewables. For example, while “…wind and solar grew nearly nine times faster than total energy demand” is a true statement, it compares the percentage growth rates and so isn’t that meaningful. The pressure to express optimism around intermittent energy sources extends broadly.

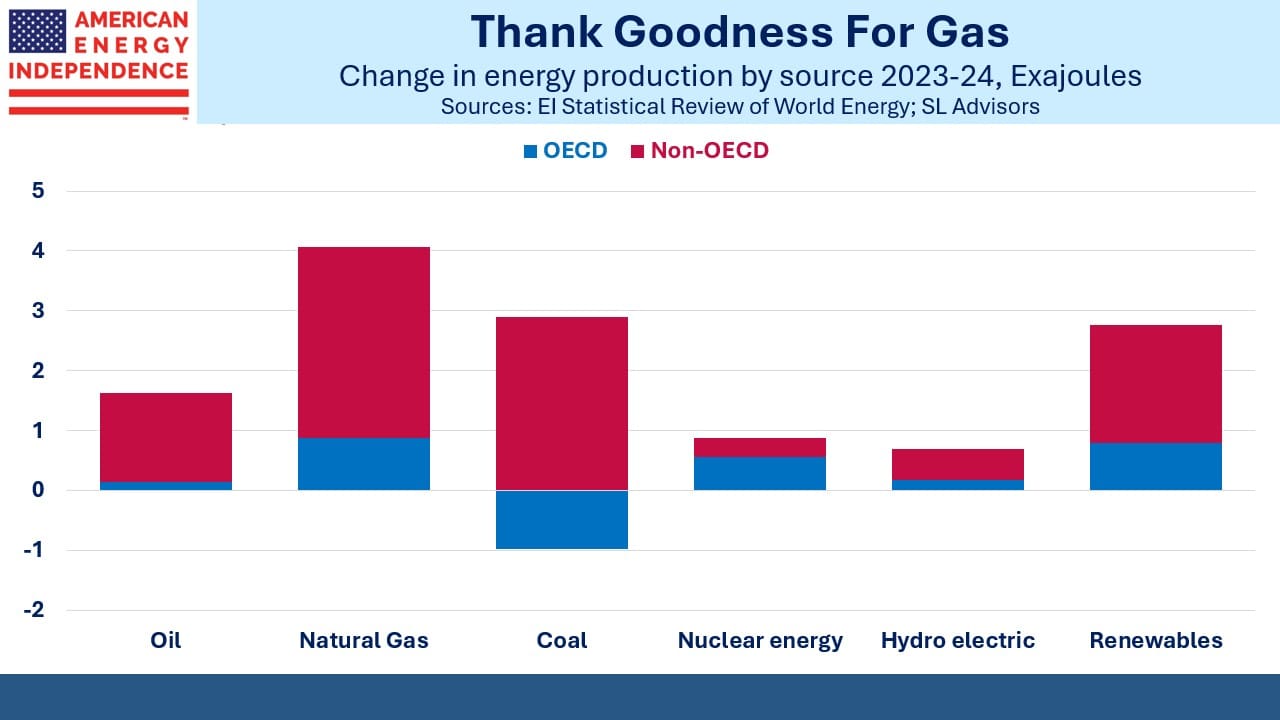

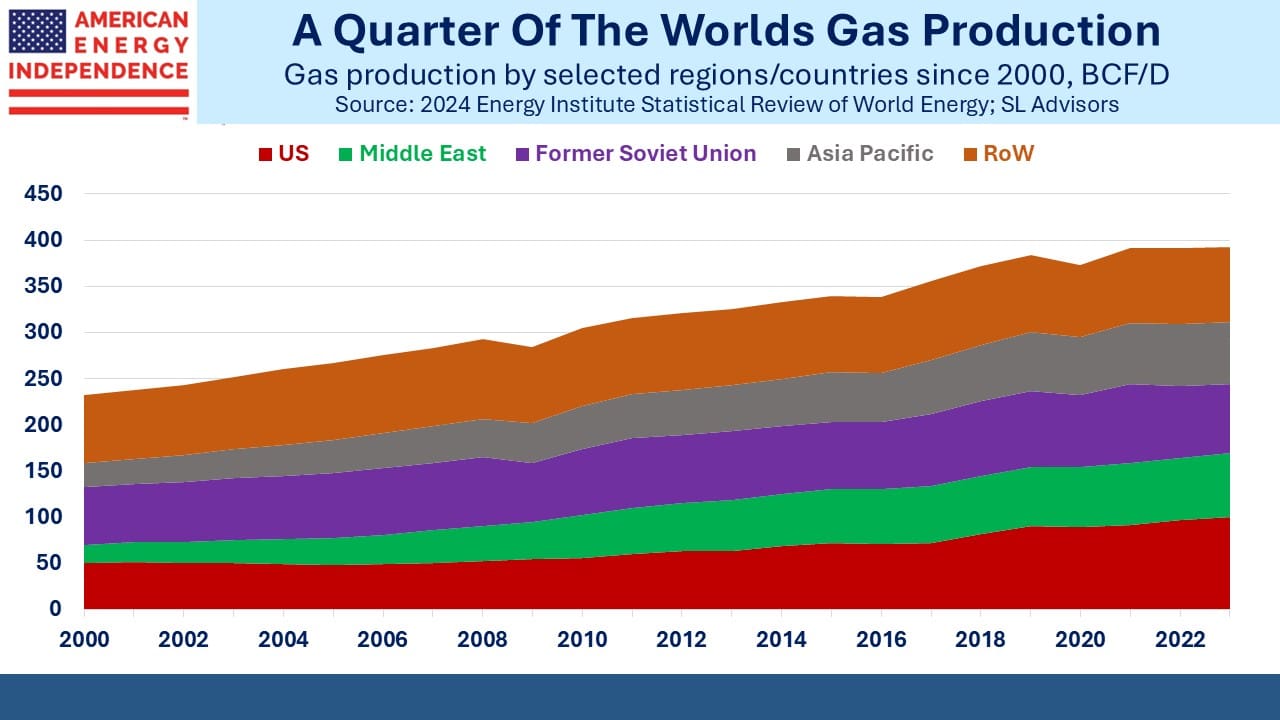

More accurate is to note that renewables production increased by 2.8 Exajoules (EJs) last year. One can cheer the 9.2% increase, or note that global energy production increased by 11.9 EJs last year and renewables were just under a quarter of this. Natural gas production grew at only 2.8%, but provided 4.1 EJs of additional energy, almost half as much again as renewables.

Natural gas met over a third of the world’s growth in energy demand last year and provided a quarter of the total. Overall, hydrocarbons fell from 87% to 86.6% of the total. It’s a true statement to say that renewables are gaining market share, reaching 5.5% last year from 5.2% in 2023. This also means that an investor in hydrocarbon energy infrastructure with a bias towards natural gas doesn’t need to be too concerned about solar and wind becoming dominant.

In 2006 Al Gore’s documentary An Inconvenient Truth raised public awareness about the risks from climate change. It also predicted that Arctic sea ice would disappear by 2013 and that Florida would disappear within decades. These were wrong in timing, but directionally had some merit.

Four years before Gore’s documentary, developed country emissions (defined as OECD) were bigger than emerging countries’ (non-OECD). If your goal was reducing them, the rich world needed to play a role. In 2003 non-OECD emissions became the larger of the two. In 2007, the year after the documentary, rich world emissions peaked.

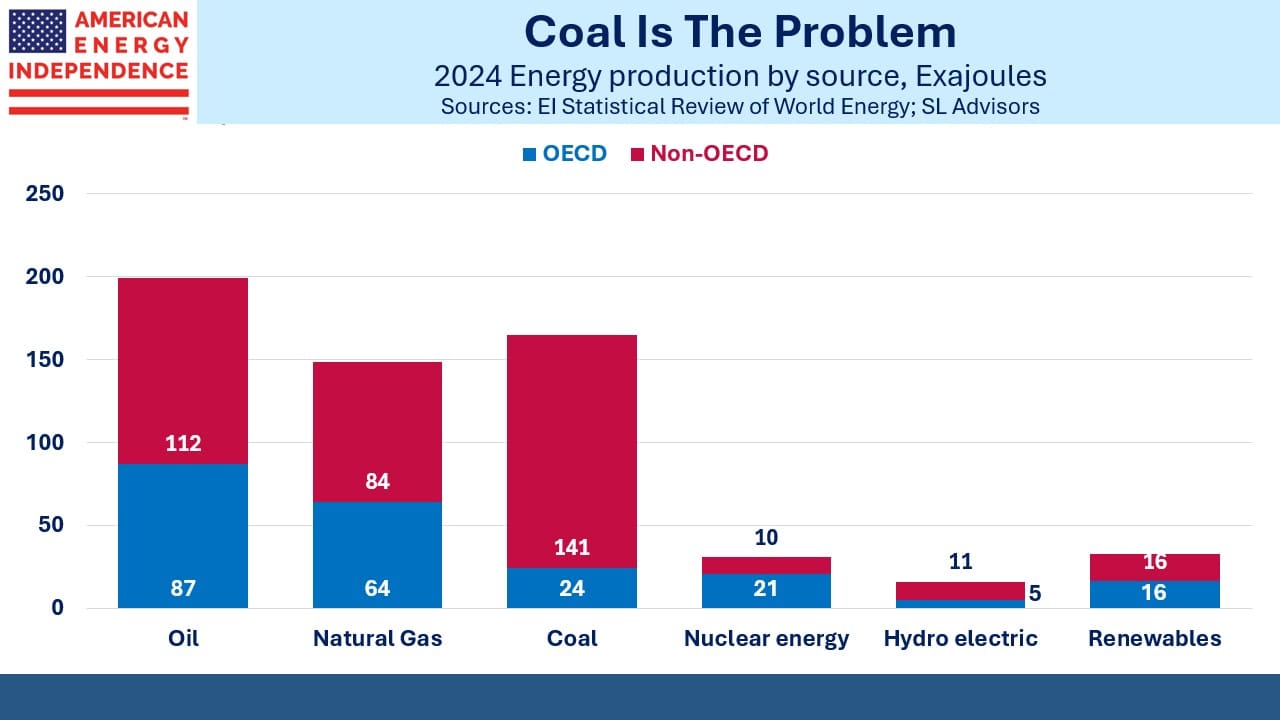

Last year, Greenhouse Gas emissions (GHGs) increased by 1.3% to 40.8 Gigatonnes (GTs, billions of metric tonnes) on a CO2 equivalent basis (CO2e). OECD countries were 12.0 GTs, non-OECD 28.8 GTs. Whatever the moral argument that per capita emissions are bigger in rich countries and should shoulder more of the burden, non-OECD populations and emissions overwhelm. Liberal efforts to block natural gas hookups and build offshore wind raise costs, reduce reliability and are irrelevant until poorer countries can change their trend.

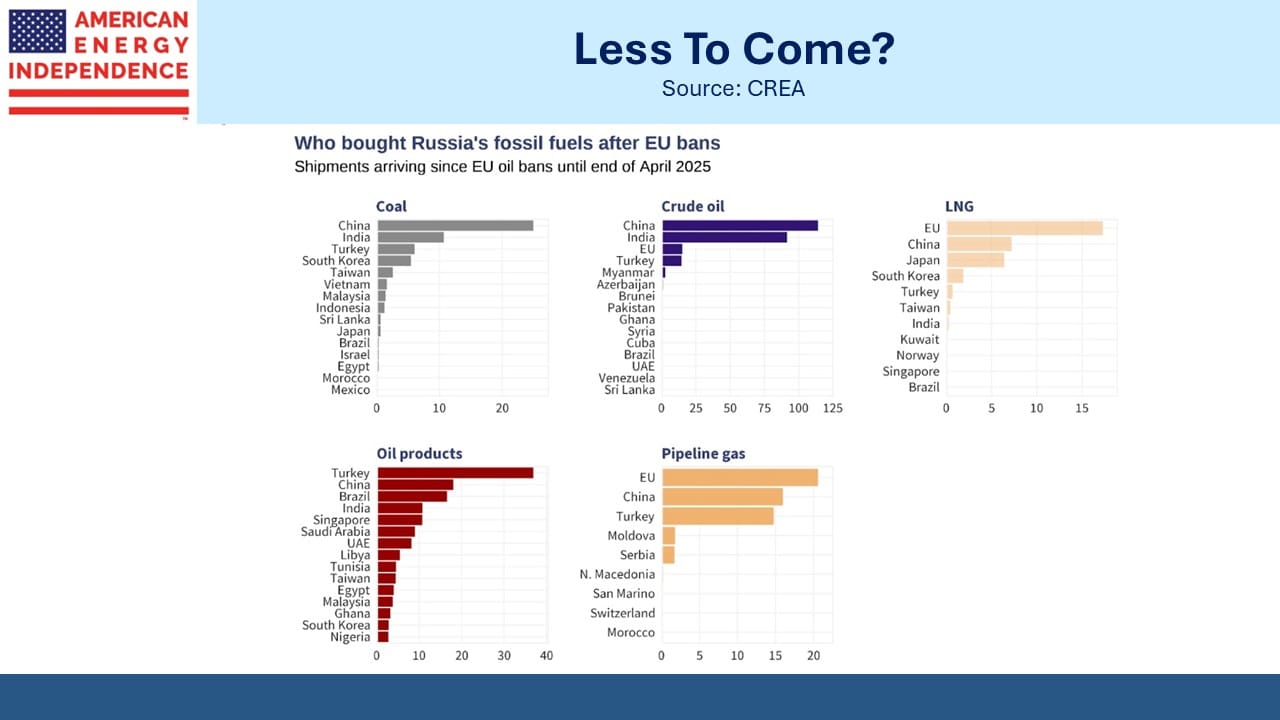

Coal is the problem, both because of local pollution as well as emissions. It’s cheap, easy to use and needs to be cut. Emerging countries increased their coal use by almost three times the reduction among rich countries. China burns 56% of the world’s output. India is 14%. Both are growing. There’s little point in having the world’s biggest EV market if they run on coal, which provides 58% of China’s electricity and 75% of India’s.

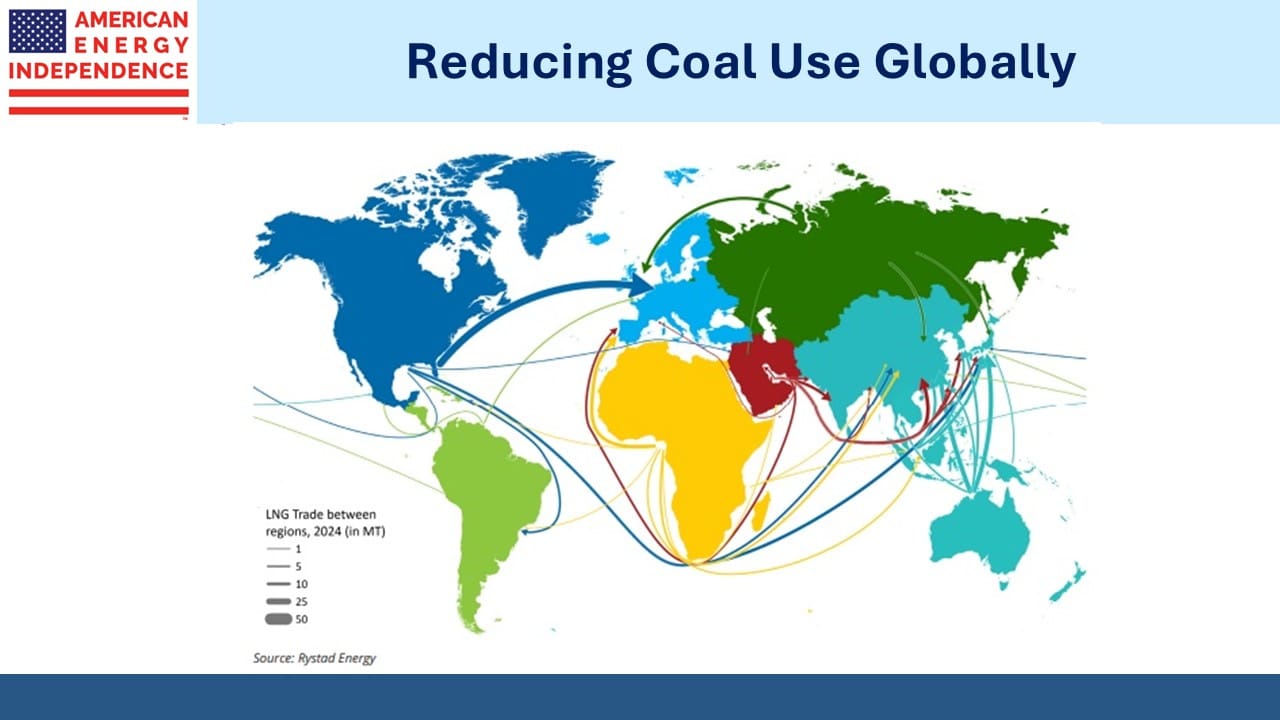

Coal displacement with natural gas in emerging Asia and elsewhere is our biggest opportunity to lower GHGs.

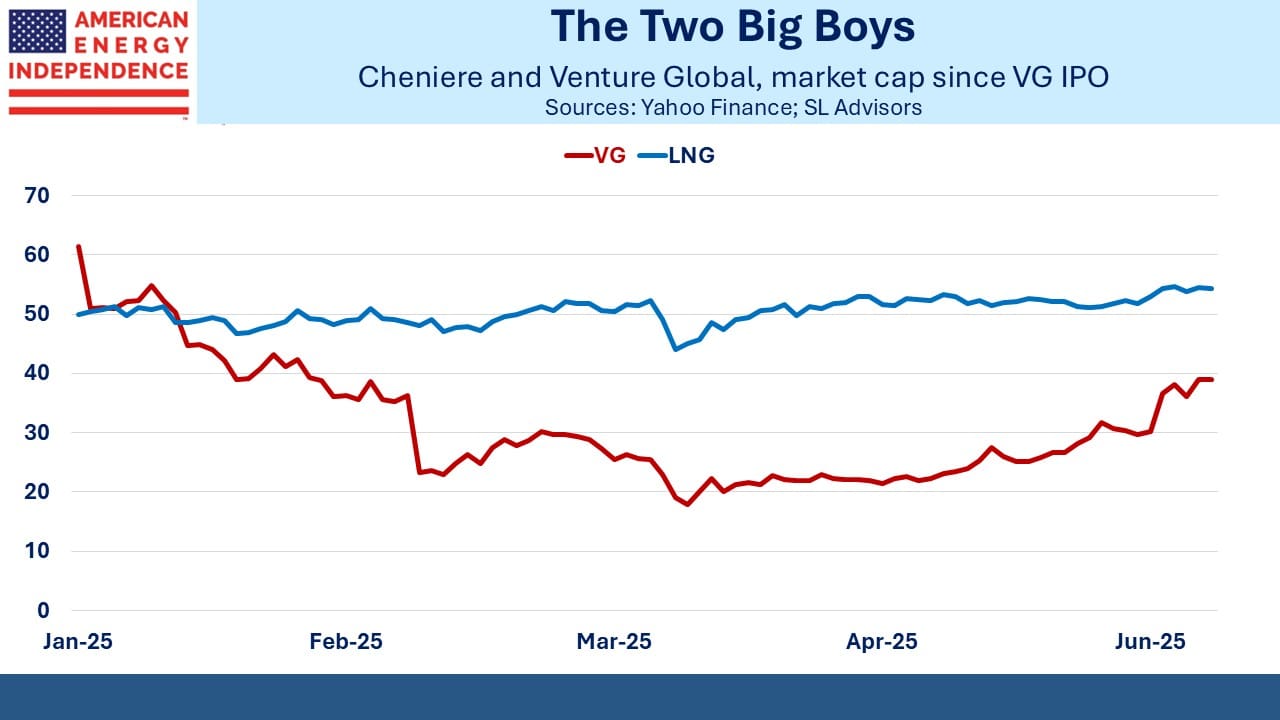

America’s LNG exports will keep growing, solidifying our role as the world’s biggest exporter. Some criticize the sector for methane leaks and the GHGs emitted in liquefaction. But the industry is addressing the issue, recognizing that many of their buyers want the full benefit of a fuel that generates roughly half the emissions of coal.

Last week Energy Transfer announced that Chevron has increased the LNG it will buy from their planned Lake Charles export facility. The twenty year offtake agreement now covers 3 Million Tons per Annum (MTPA), up from 2 MTPA.

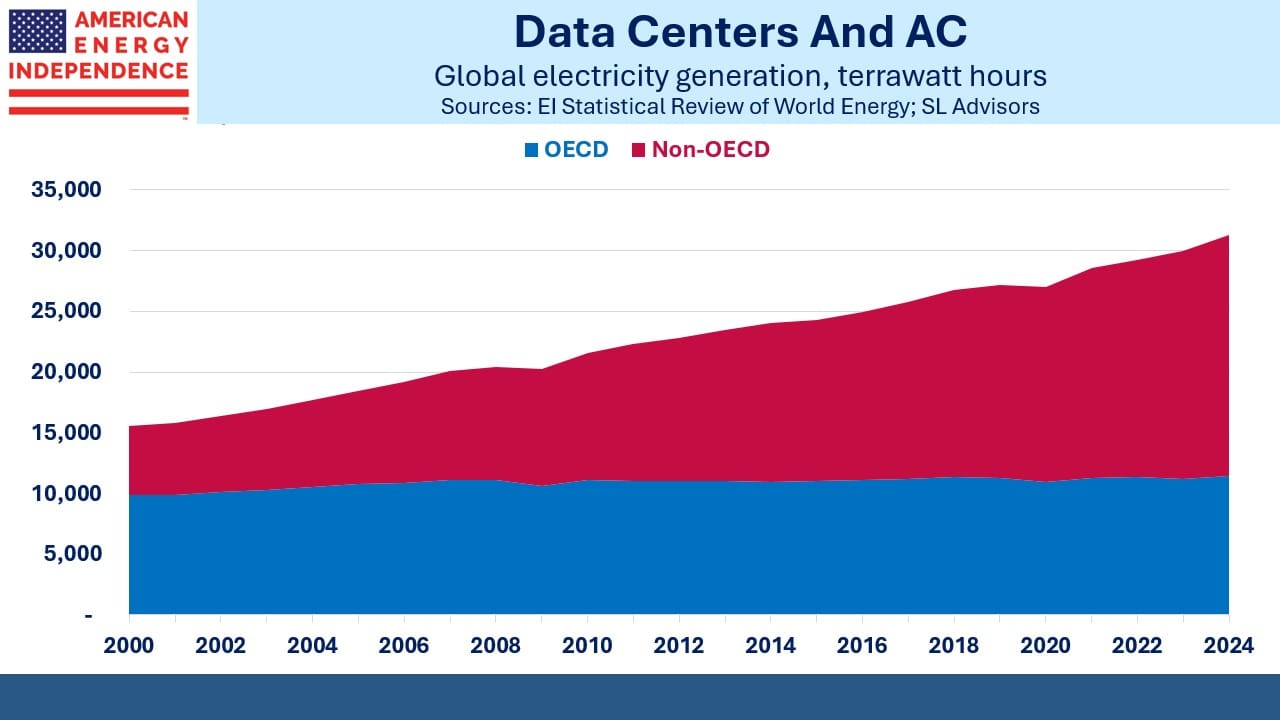

Global electricity production grew by 4% last year, well ahead of the ten year 2.6% CAGR (compound annual growth rate). Much has been written about the impact of data centers, which are causing a sharp jump in demand in the US. OECD power consumption grew at a 0.4% CAGR over the past decade, and 4.2% in emerging countries.

AC is a big driver in countries such as India, which makes increased LNG exports critical to curbing their voracious appetite for coal.

Naples, FL is one of the most politically conservative places in America. It’s very red, and its population includes quite a few who would assert climate change isn’t real. Nonetheless, one local church that has endured repeated flooding from storm surges, including last October, has concluded that such events are more likely and has decided its best defense is to raise the entire building. For some, pragmatism trumps conviction.

We have two have funds that seek to profit from this environment:

Energy Mutual Fund Energy ETF