Every Issue Is Linked To Trade

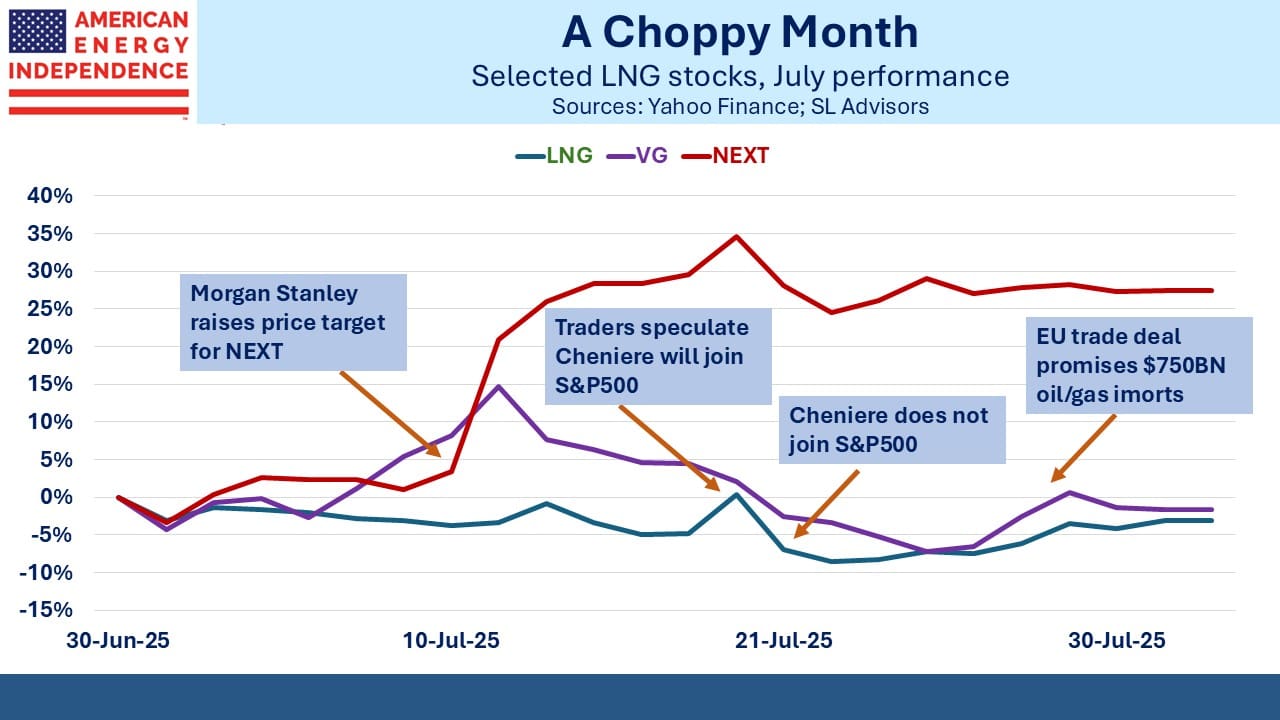

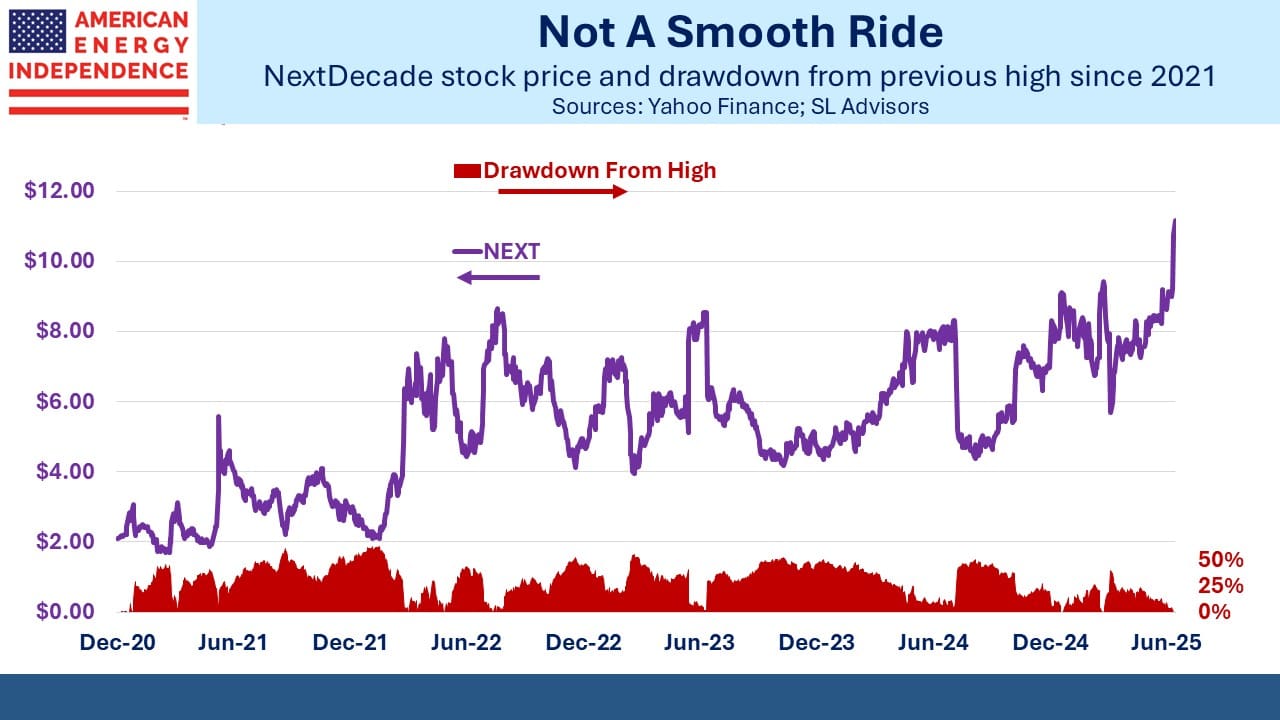

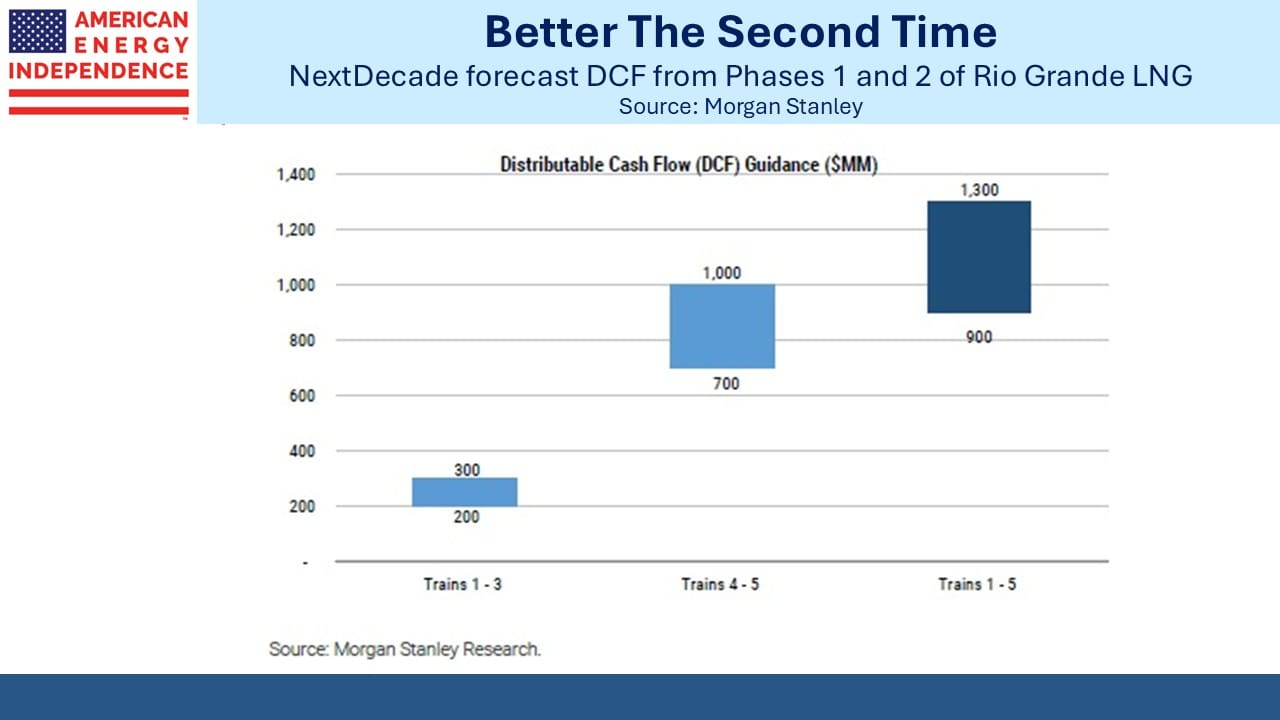

July was action-packed for LNG names. On July 11 Morgan Stanley raised their price target on NextDecade (NEXT) to $15, having last moved it to $10 in October 2022. The stock rose 18% to $10.77 on the news and added further gains during the month. Morgan Stanley’s upgrade was the only news of note, but their more bullish view on the company led the market to reprice.

Venture Global (VG) traded up in sympathy with NEXT, but since it wasn’t mentioned in the Morgan Stanley report, its gains slipped away.

Cheniere’s price target was left unchanged at $255. But following the International Court of Arbitration’s July 18th ruling that Chevron’s acquisition of Hess could proceed, Cheniere rose as traders bet it would finally be added to the S&P500 by replacing Hess. It fell when Block was chosen instead.

The US-EU trade agreement boosted LNG stocks because of the commitment by Europeans to buy $750BN of US oil and gas over three years. This was quickly derided by analysts. Criticisms included (1) the EU doesn’t buy oil and gas, private companies do, so it’s unclear what mechanism they would use to meet this commitment (2) no written agreement was released, so there are no visible consequences for failure, and (3) US oil and gas exports in total are currently around $150BN.

Reaction to the trade deal across the EU has been negative. Europe’s Summer of Humiliation in the Financial Times Op-Ed section reflected widely-held sentiments.

The deal exposed Europe’s negotiating weakness. With no one in charge, their decision-making process is necessarily slow and defensive, which dilutes the heft their economy might otherwise wield. They’re scrambling to develop a military capability to confront their aggressive eastern neighbor.

These issues clearly played a role, which is why the Euro sank 3% in the days following the deal. The White House linked trade and national security to exploit these weaknesses to America’s advantage. It’s hard to think of a previous Administration that took such a stance.

How investors think about the prospects for increased US energy exports to Europe has been a hotly debated topic among your blogger’s investment team. It’s easy to conclude the numbers are implausible.

The EU commitments on oil and gas purchases can be dismissed as aspirational given the figures outlined above. But the trade deal showed who holds the cards. Trump is likely to abruptly rescind any agreement with little warning.

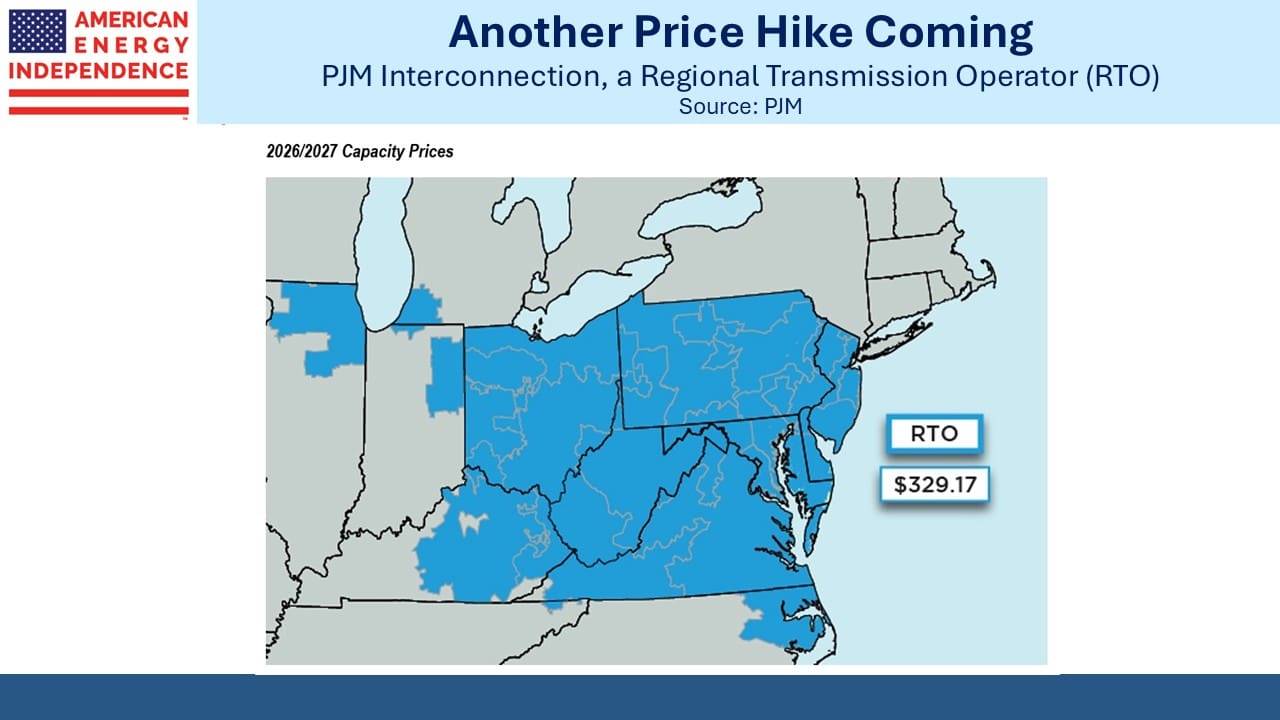

When Cheniere or VG are negotiating a long-term LNG supply contract with a big European buyer, they’re likely to complain to the White House if unable to reach a conclusion. If EU rules rather than commercial terms are the sticking point, “temporary punitive tariffs” may be needed to induce a more co-operative EU regulatory structure. If European buyers don’t sign some additional long-term LNG contracts in the months ahead, there are likely to be consequences.

The US has already introduced tariffs into relations with Brazil to halt the prosecution of right-wing former President Jair Bolsonaro. The 35% tariff on Canadian goods announced Friday is in part because PM Mark Carney showed he is “tone deaf” by recognizing Palestinian statehood, according to Commerce Secretary Howard Lutnick.

Trade issues are being linked like never before to promote US interests.

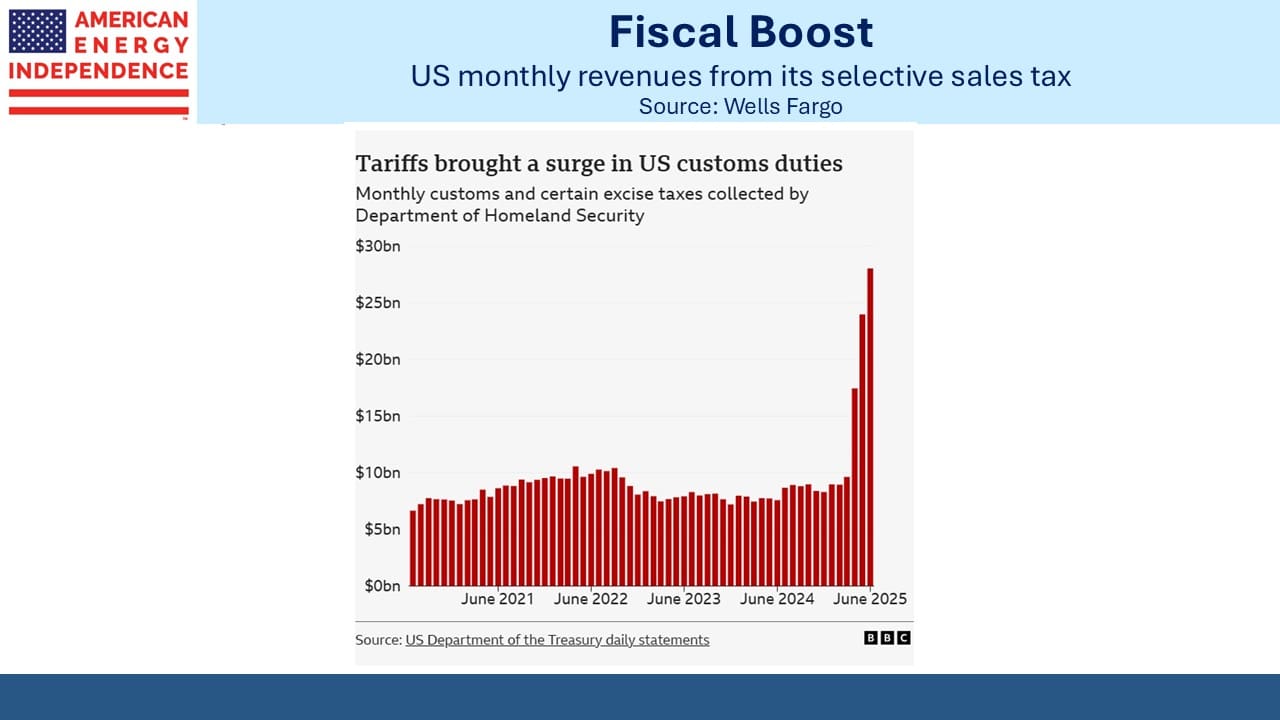

So far, tariffs have been less disruptive than many expected. One might even say that those who understand economics forecast a dire outcome, while those who don’t just went ahead and implemented them. The net result looks like a Federal sales tax applied to imports. It’s running close to $30BN per month. Even for the US-sized budget deficit this is real money – equal to more than a third of our defense spending.

State-level sales taxes are uncontroversial, and most states have one. We now have a Federal sales tax applied selectively on foreign goods. Implementation has been capricious, inducing equity market volatility. Some industries such as autos with their cross-border supply chains have absorbed big losses. There may yet be an uptick in prices, although few would worry that a sales tax is inflationary.

The world hates the re-ordered trade system. Swiss lawmakers were left “in shock” at the abrupt imposition of a 39% tariff on Friday.

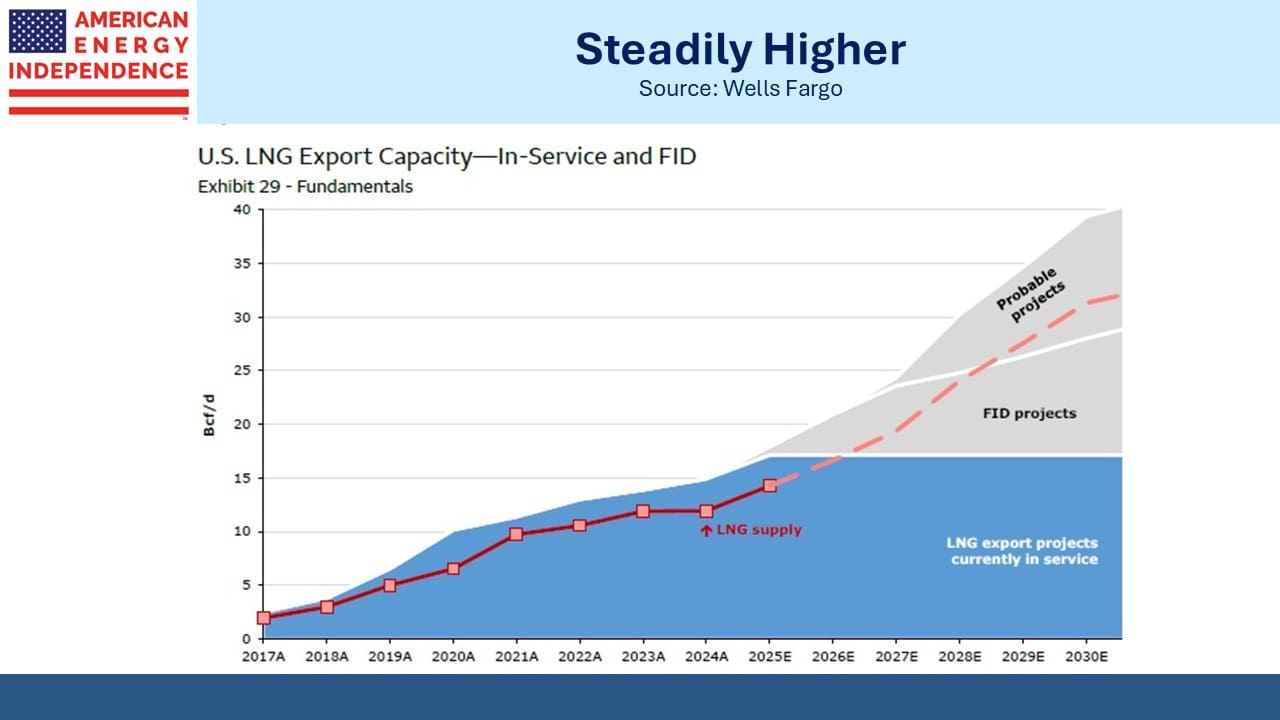

America, objectively, seems to be doing fine. The outlook for growth in US LNG exports continues to improve.

We’re modifying the current Sunday/Wednesday twice-weekly blog schedule to be weekly, on Sundays, with opportunistic updates during the week as market events dictate. We think this will improve the quality and relevance of this blog’s output.

We have two have funds that seek to profit from this environment:

Energy Mutual Fund Energy ETF