Gas Kept Us Cool Last Week

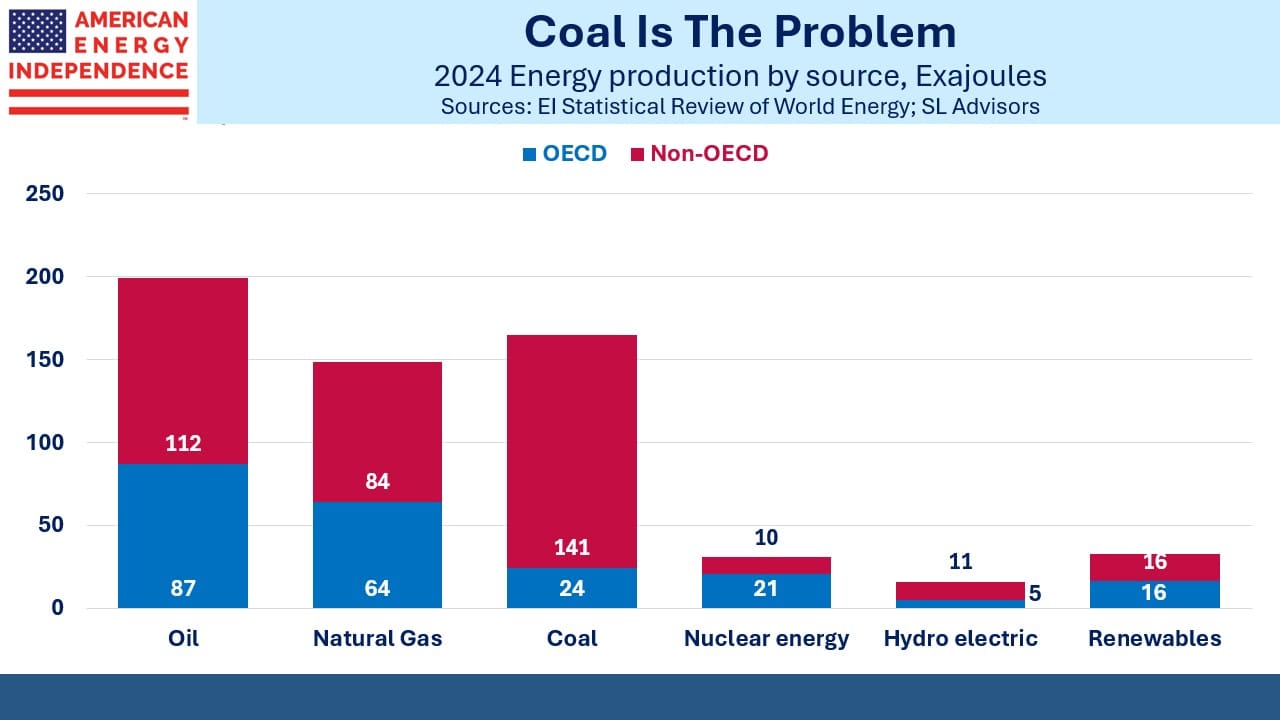

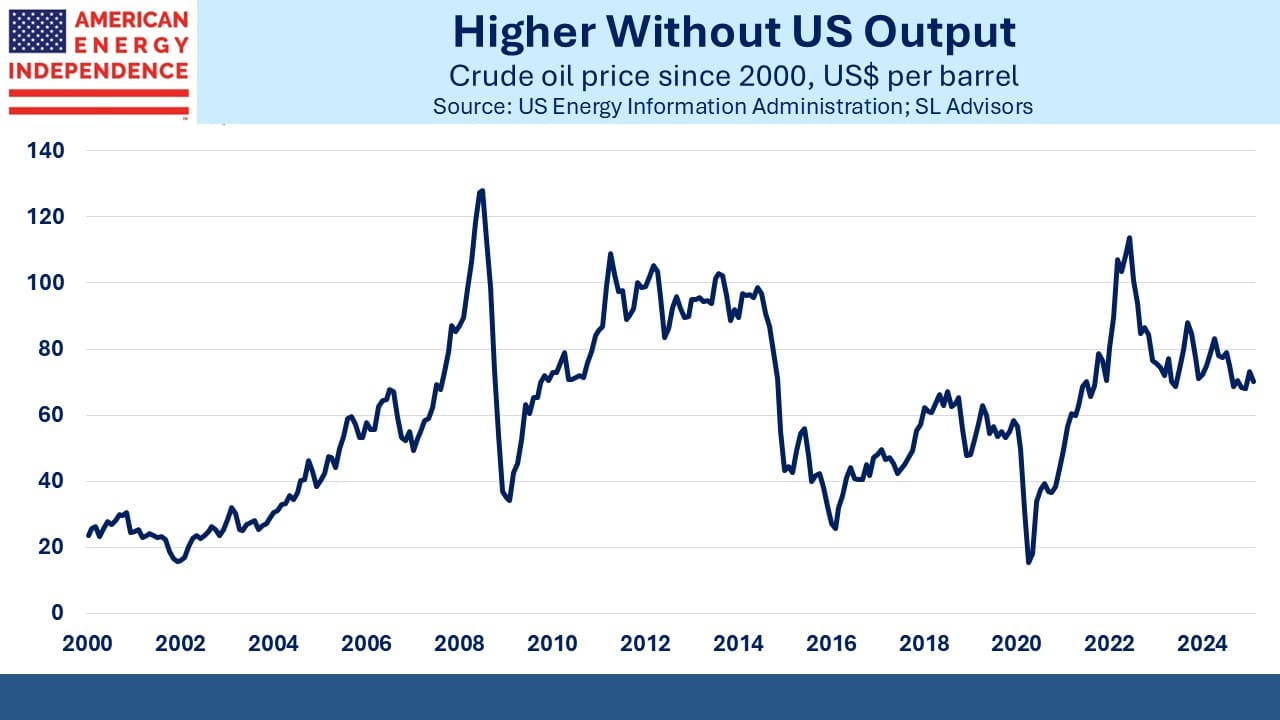

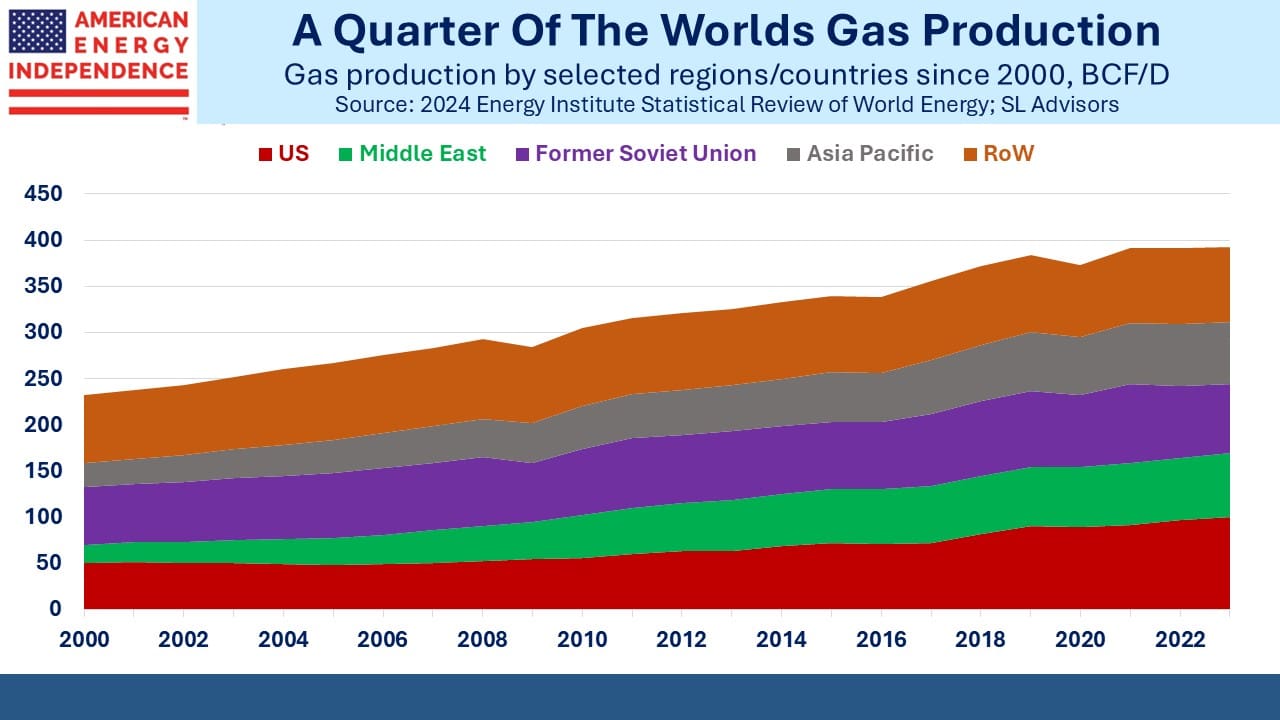

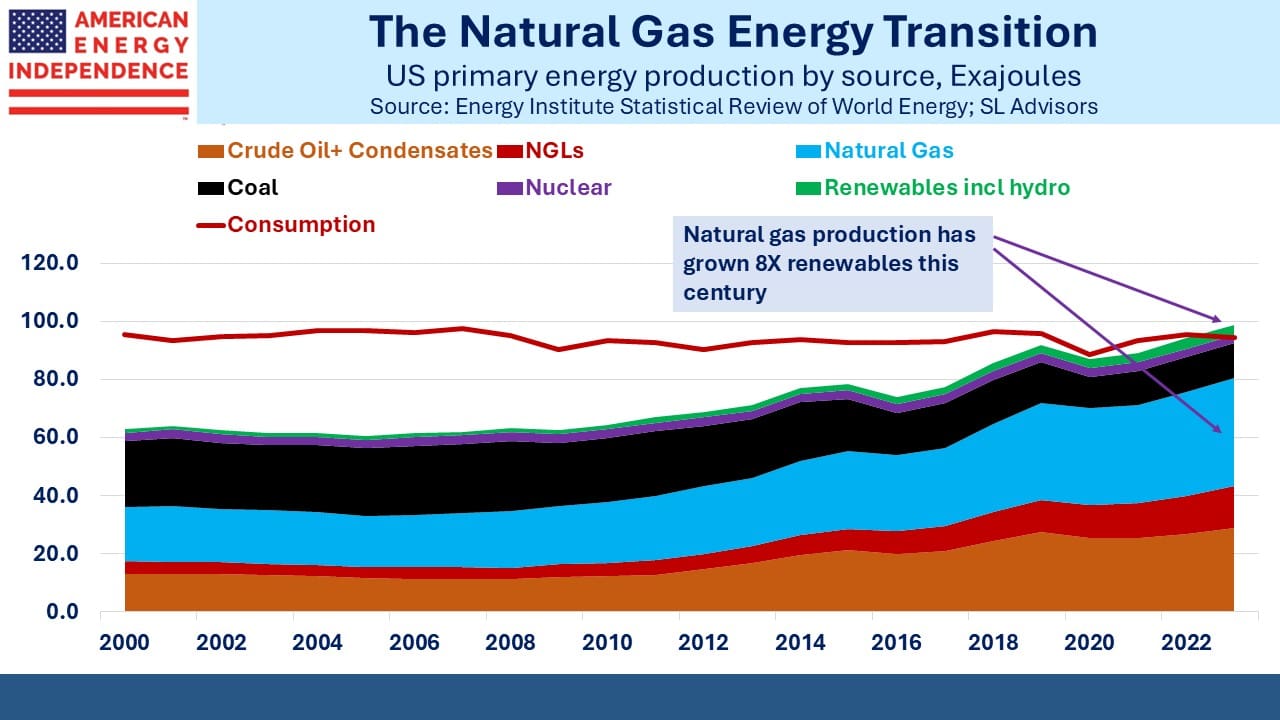

Our power infrastructure survived last week’s heatwave, which saw the PJM Interconnect system peak at an almost twenty year high of 160,560 Megawatts on June 23. Natural gas provided 44% of generation, with solar at 6%. The ISO-NE system that covers New England saw peak demand a day later. This was met 47% by natural gas and 4% from renewables (wind, solar and batteries).

There is a revival of interest in new pipeline projects to serve the northeast. In recent years politically motivated regulatory hurdles led to several cancellations. In 2016 Kinder Morgan (KMI) shelved Northeast Energy Direct (NED) which was to transport natural gas from Pennsylvania through New York and into New England. They were unable to obtain enough firm commitments from power companies who feared future limits from state governments on their ability to use gas.

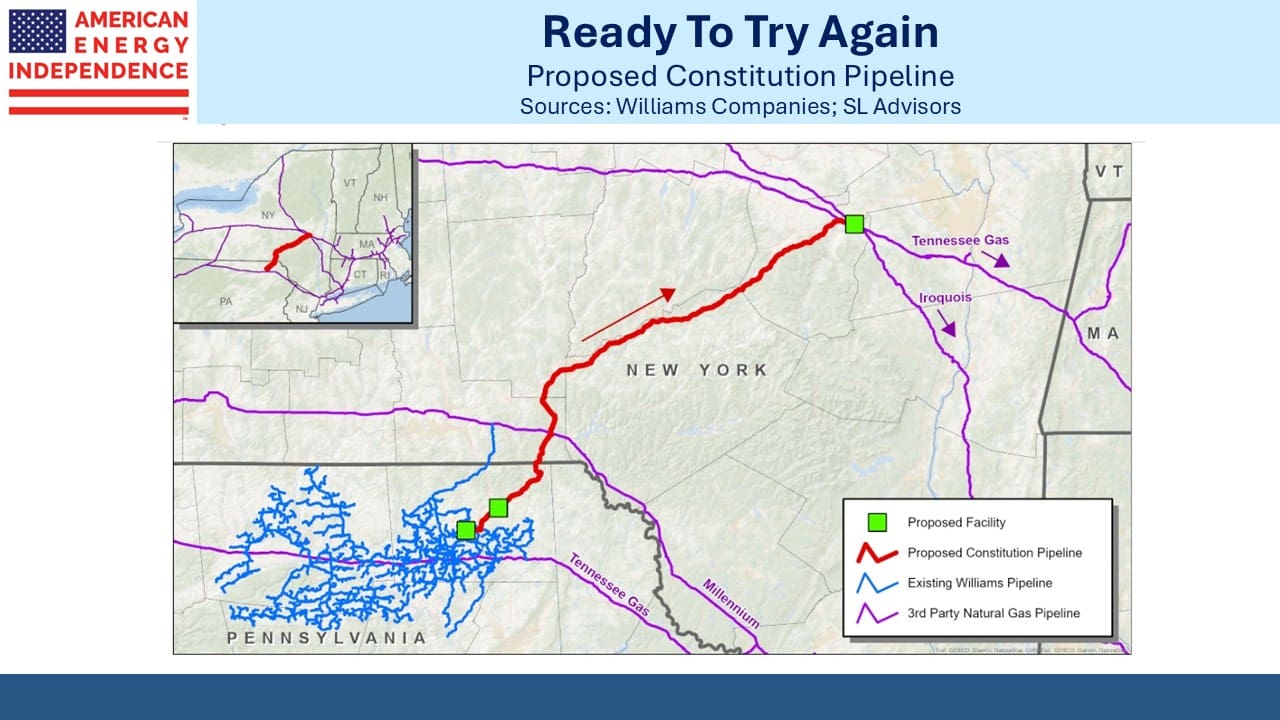

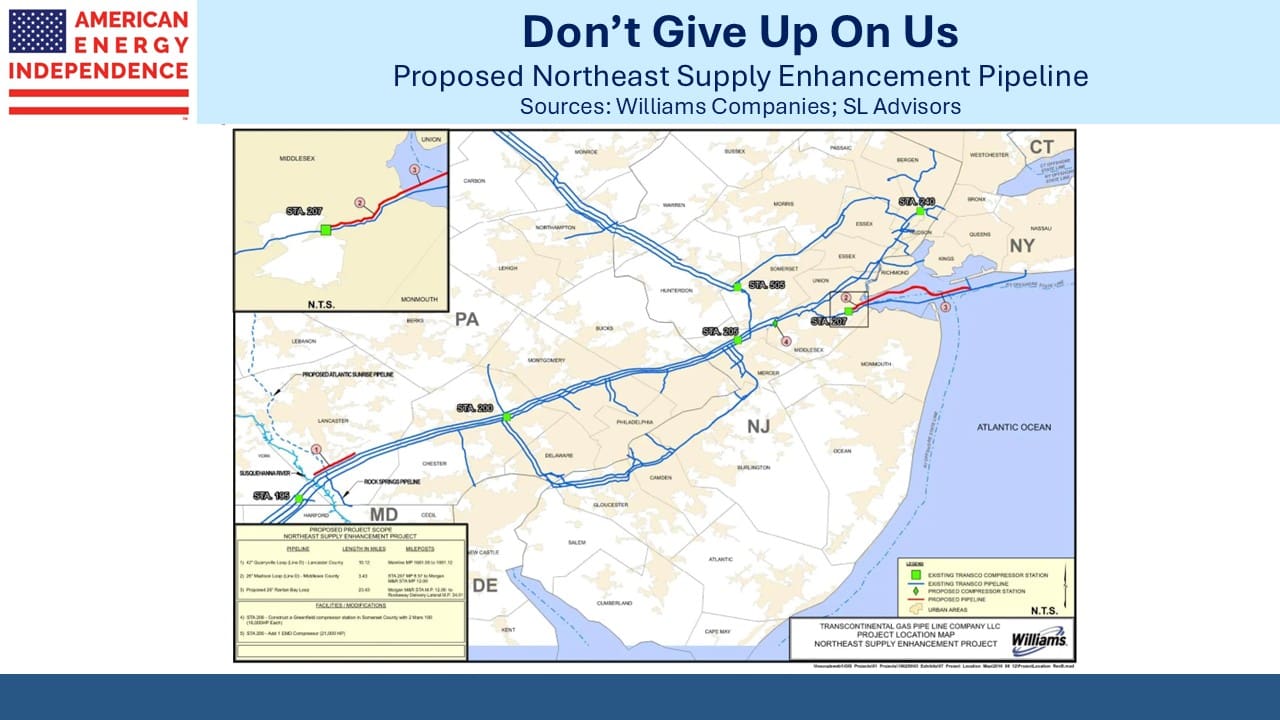

In 2020 Williams Companies (WMB) canceled Constitution Pipeline which was to link Pennsylvania and New York because of difficulties obtaining water permits. Last year they canceled the Northeast Supply Enhancement Pipeline (NESE) that was to run from Pennsylvania through New Jersey to New York City, also because of problems with water permits.

Constitution has now been restarted, with an in-service date of 3Q27.

NESE has also been restarted, with an in-service date of 4Q27. Residents of New York and New Jersey are fortunate that WMB still has an appetite to try and complete these projects given the hostility to reliable energy from their state governments.

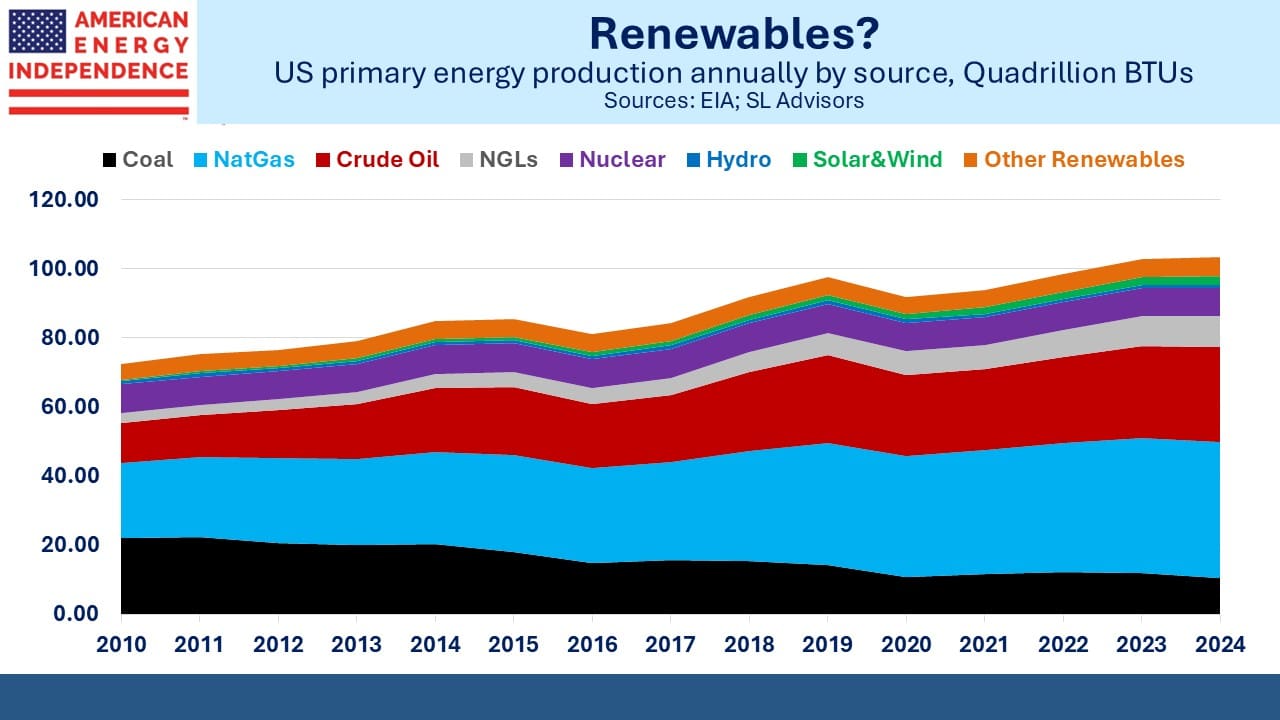

So far KMI hasn’t indicated they’ll restart NED. But the shift is palpable, driven by the failure of renewables to meet expectations and the Administration’s reversal of energy policies followed under Joe Biden.

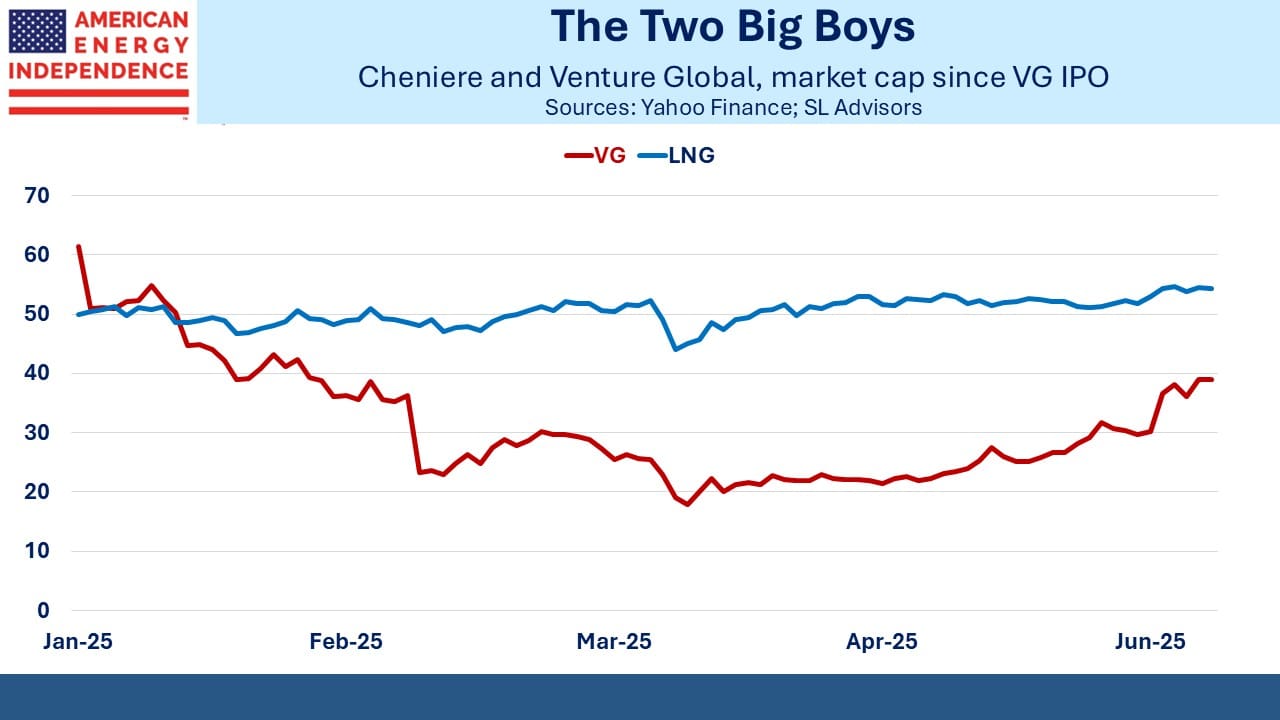

JPMorgan’s Energy, Power, Renewables, and Mining Conference provided positive news for domestic natural gas demand with Exxon Mobil (XOM) confirming that Golden Pass LNG will start operations by the end of the year. The project is situated on the Texas side of the Sabine-Neches Waterway, opposite Cheniere’s Sabine Pass LNG terminal which is on the Louisiana side. XOM owns 30% of the project and Qatar Energy 70%.

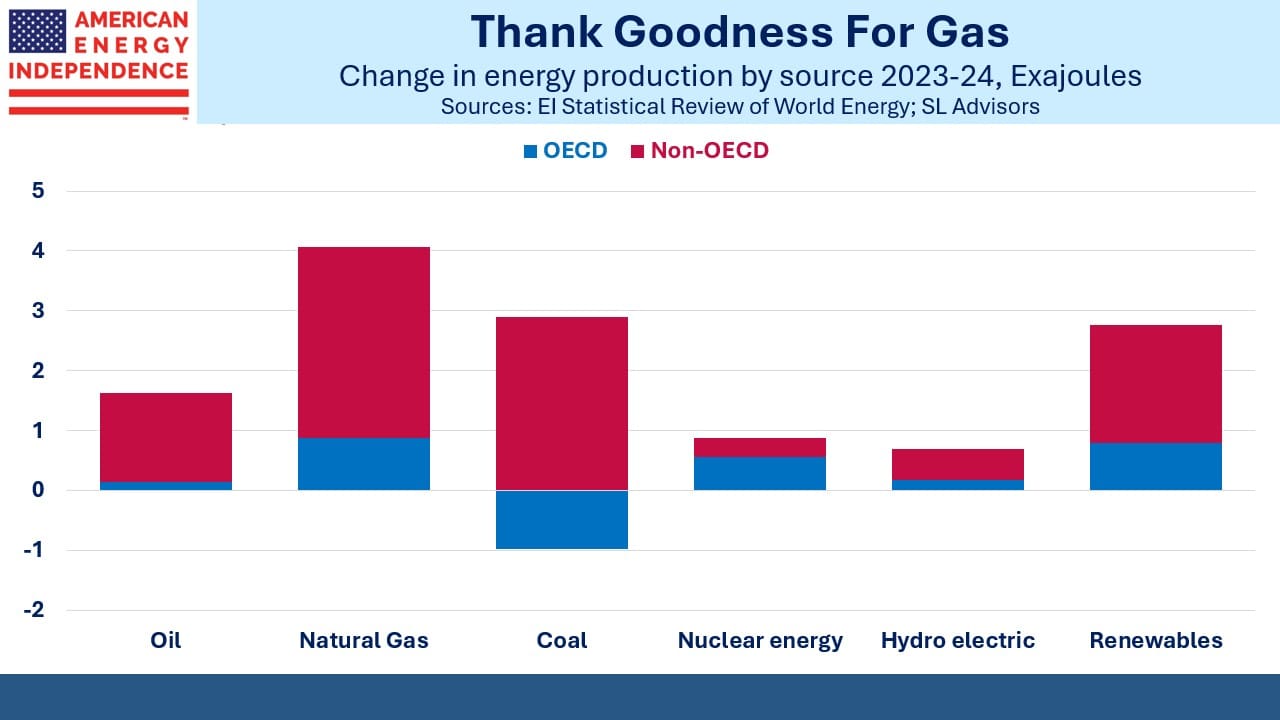

Energy Secretary Chris Wright wrote an op-ed last week justifying the shift against renewables in the One Big Beautiful Bill (OBBB) currently making its way through Congress. He compared the intermittency of solar and wind with the value of an Uber ride that couldn’t commit to a pickup time or drop-off point.

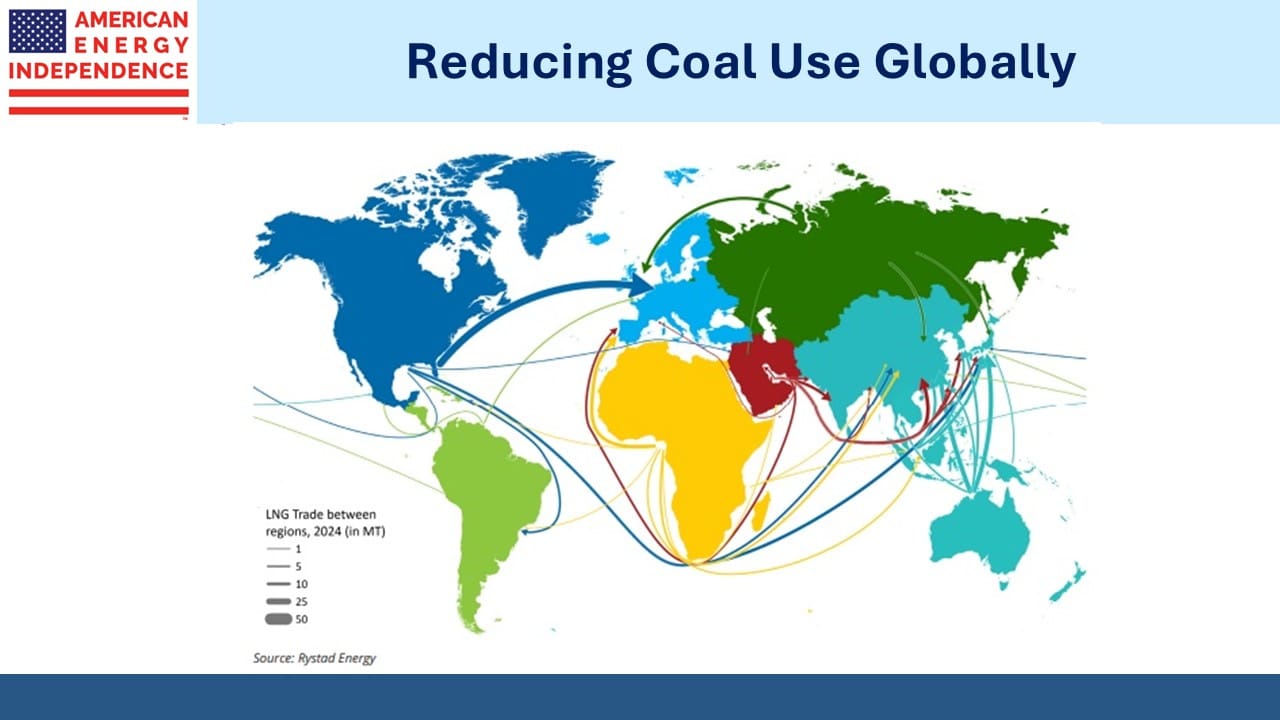

Other than his support for coal, we think Wright’s energy policies are good.

The OBBB has caused some big swings in renewables stocks as traders react to changes to the draft language. The damage to renewables businesses in the US is likely to last well beyond the current Administration even if the Democrats reclaim the White House in 2028, because investment timelines are longer than the presidential election cycle.

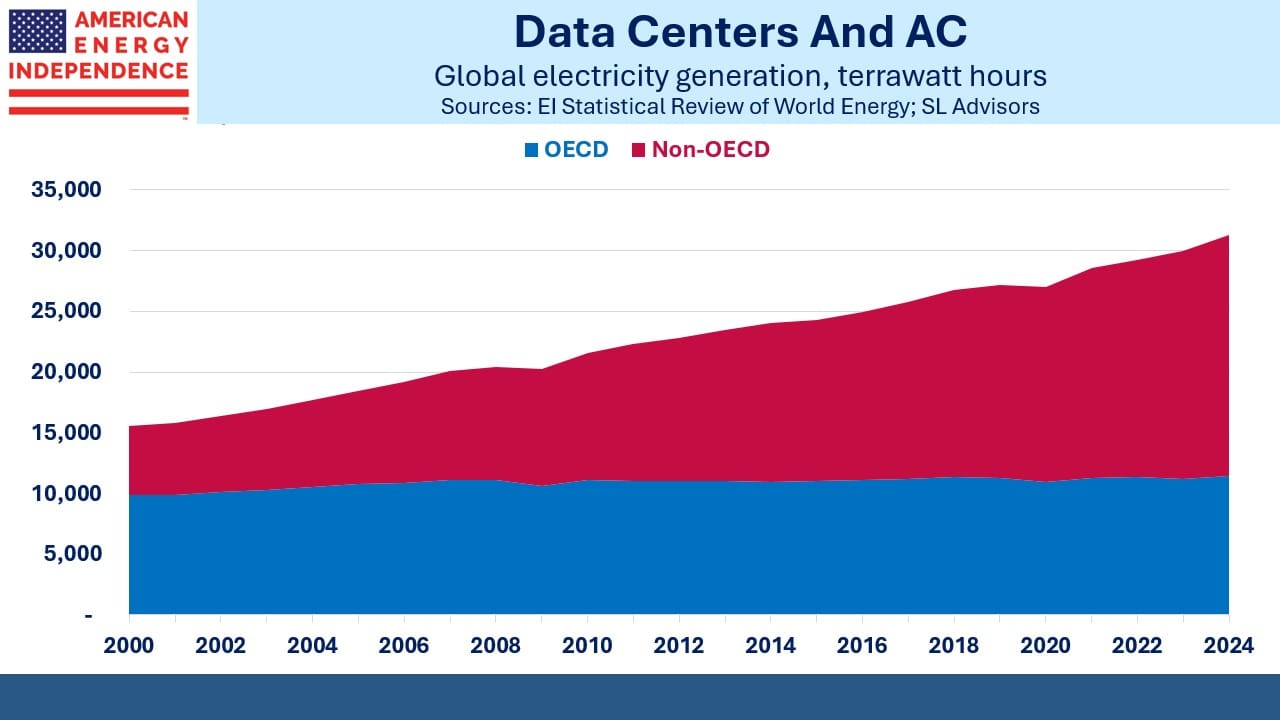

The Texas state legislature passed a new law allowing data centers to be cut off from the grid during times of high demand. This reflects the growing electricity needs of data centers and their limited political influence. Once constructed, they create few jobs since all that’s required is a handful of IT specialists to monitor the thousands of computers supporting the AI revolution.

This will boost Behind The Meter (BTM) solutions which deliver natural gas to a dedicated power plant, bypassing the grid. WMB is developing a reputation for offering market leading solutions as they’re able to combine access to large quantities of gas through their existing pipeline system with marketing knowledge and control of relevant plots of land.

Data centers often like to connect with the grid even if their main supply is BTM because it provides back-up when their gas power plant is down, most likely for maintenance. Data centers are increasingly seeking very consistent power supply with virtually no downtime. The current standard for maximum acceptable loss of power is reported to be as little as three seconds per year.

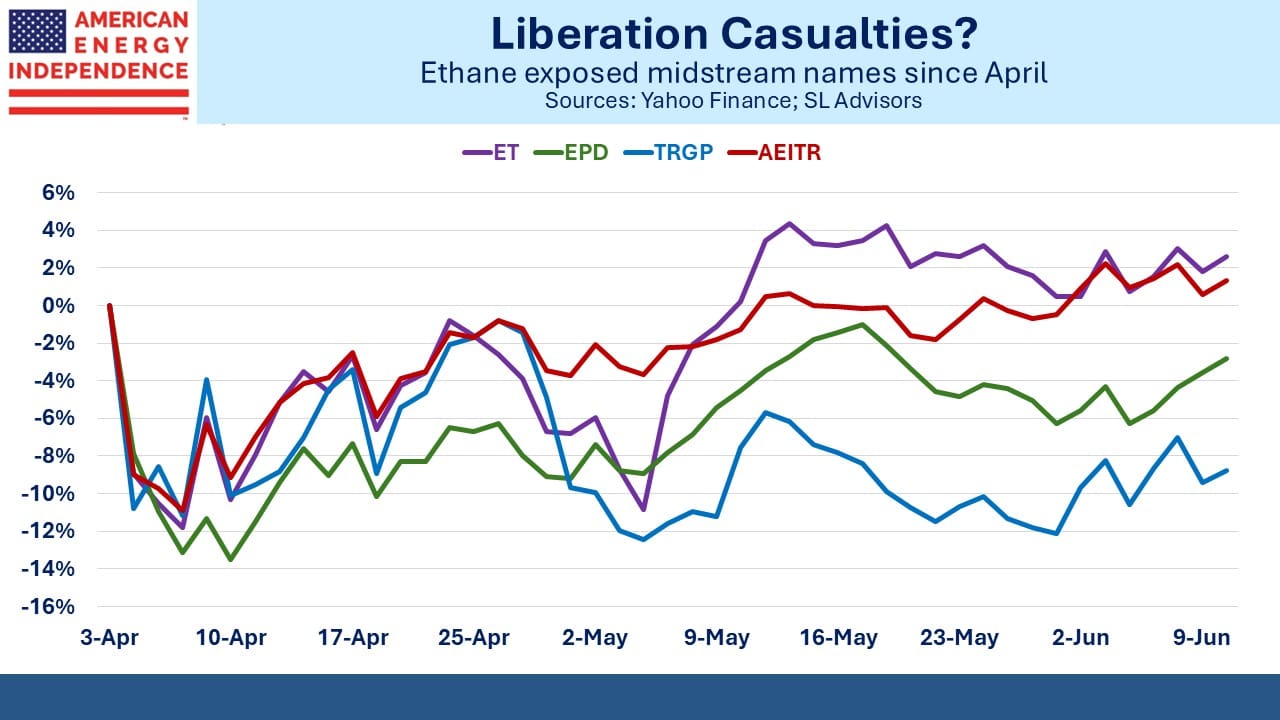

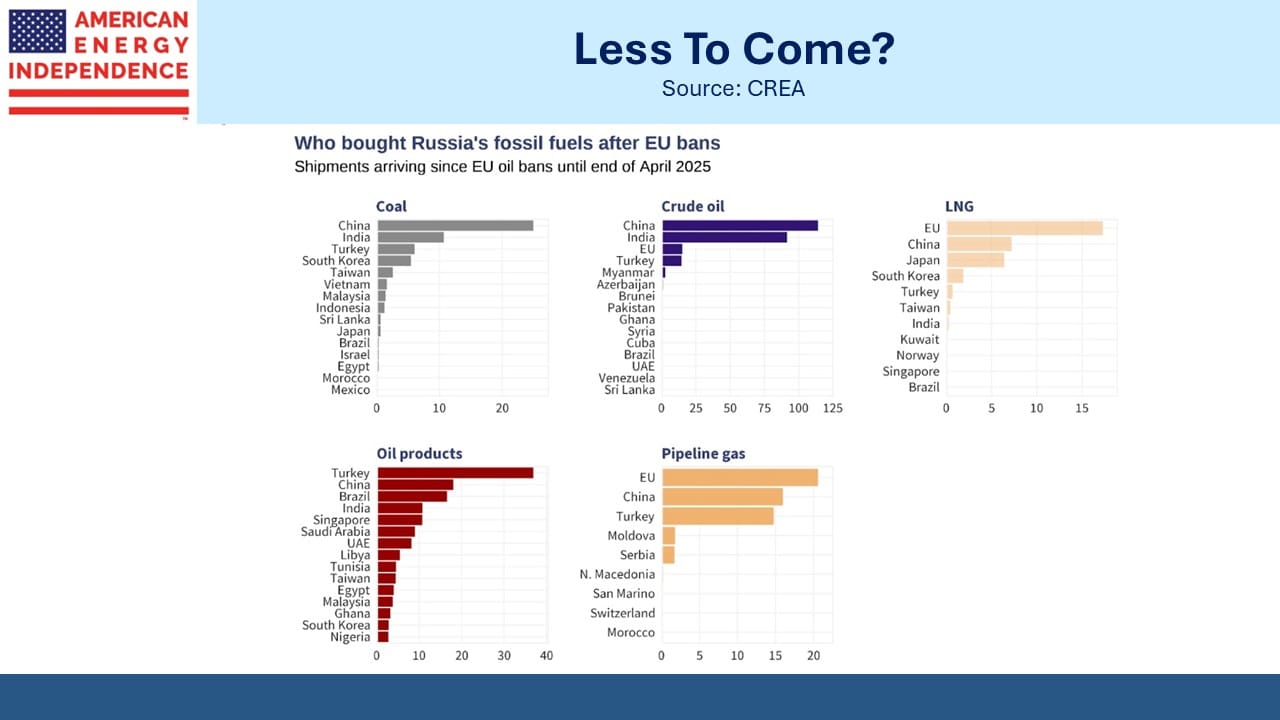

Lastly, the President had a good foreign policy week, but the implementation of tariffs continues to create uncertainty. The US sells ethane to China, and neither side has an easy replacement. Shortly after Liberation Day analysts worried that China might impose reciprocal tariffs on US ethane but demurred since they have a petrochemical industry designed to receive it.

Then the US announced a license requirement for ethane exports and even though Enterprise Products Partners and Energy Transfer both made “emergency applications” they were not forthcoming. The latest twist in the ethane trade is that ethane tankers can be loaded and travel to China but not unload.

It’s unclear if any ethane tankers will be dispatched under such circumstances. US trade policy remains capricious.

We have two have funds that seek to profit from this environment:

Energy Mutual Fund Energy ETF