Infrastructure’s Energy Demands Attention

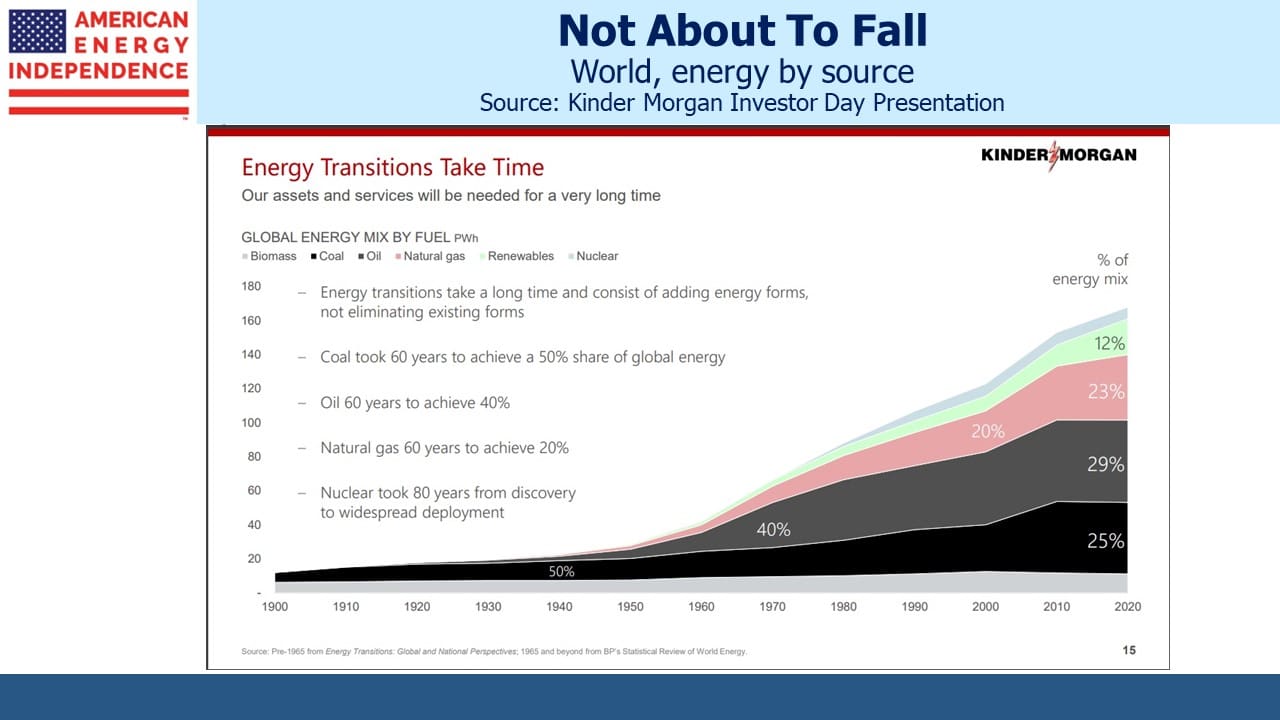

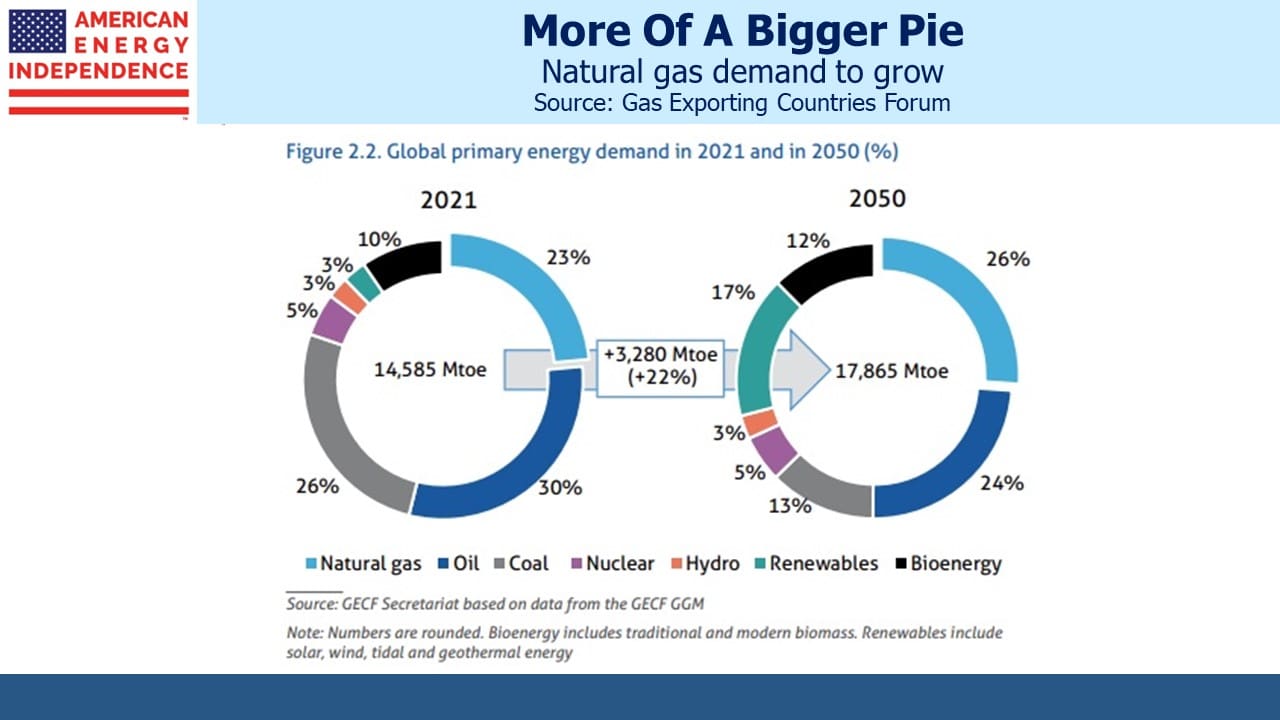

The “energy” in midstream energy infrastructure is often the primary consideration of potential investors. It probably began with the increased investment during the shale revolution, and the energy transition generated questions about energy mix and stranded assets. But nowadays capital discipline beats growth capex while without energy security there is no transition.

It’s time to emphasize the “infrastructure” in midstream energy infrastructure.

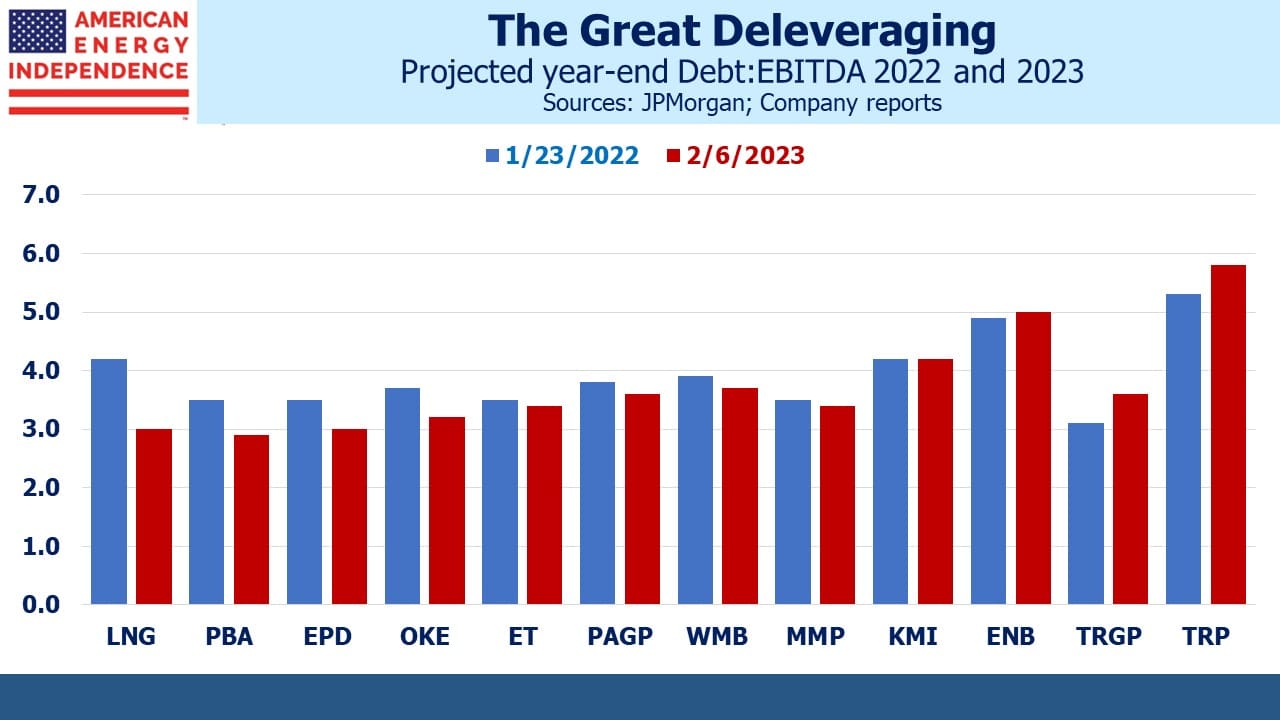

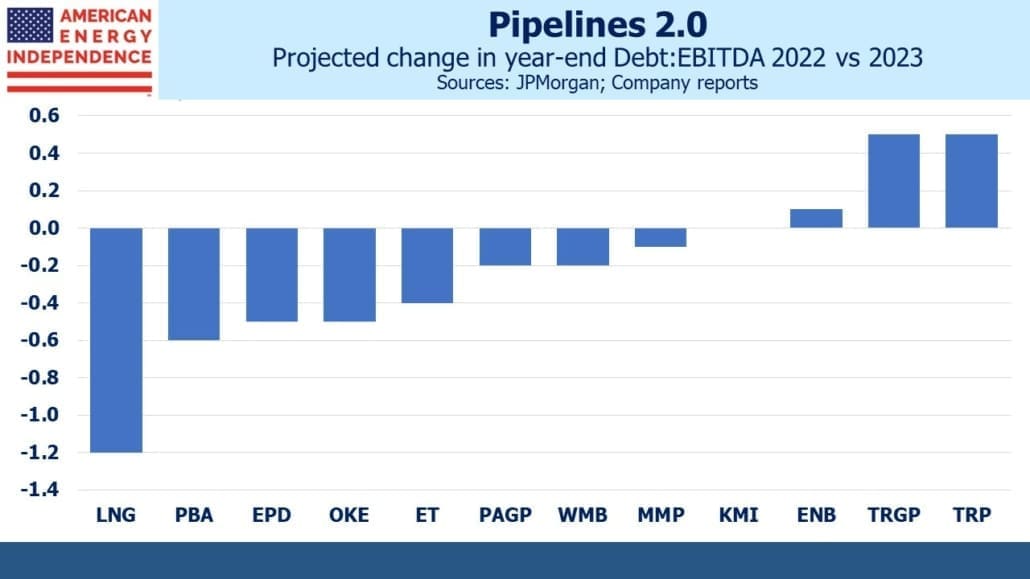

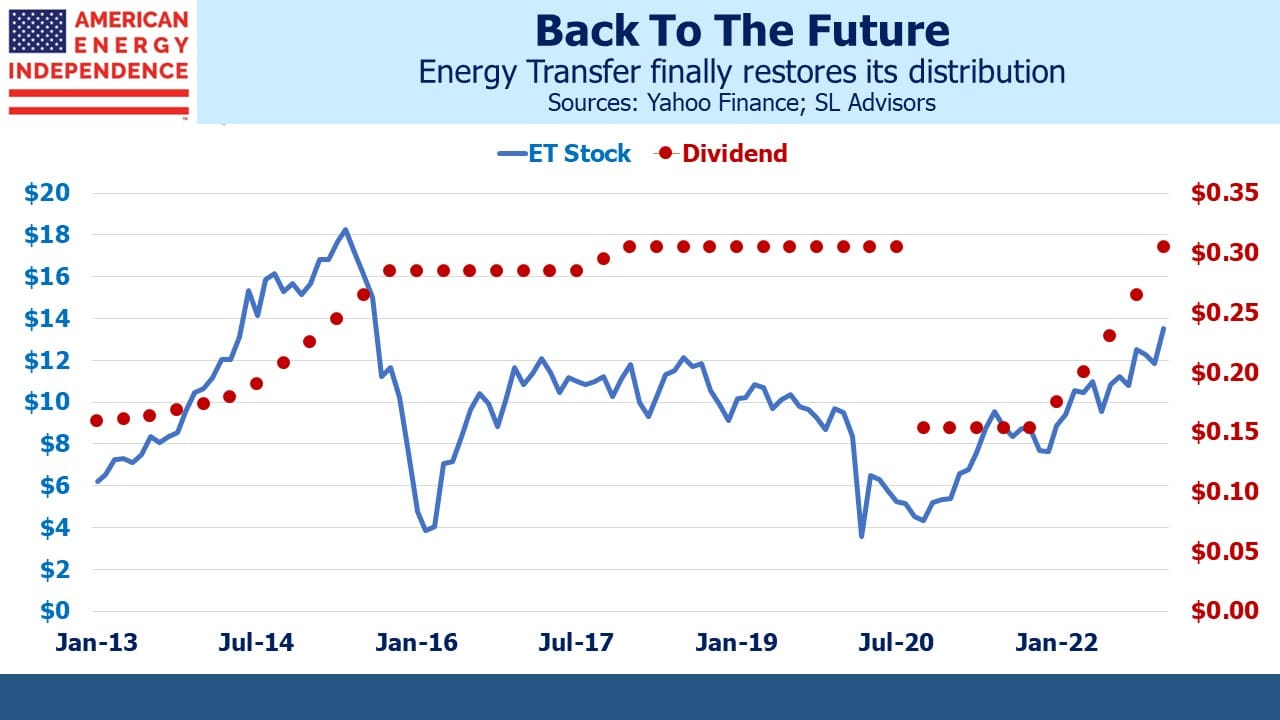

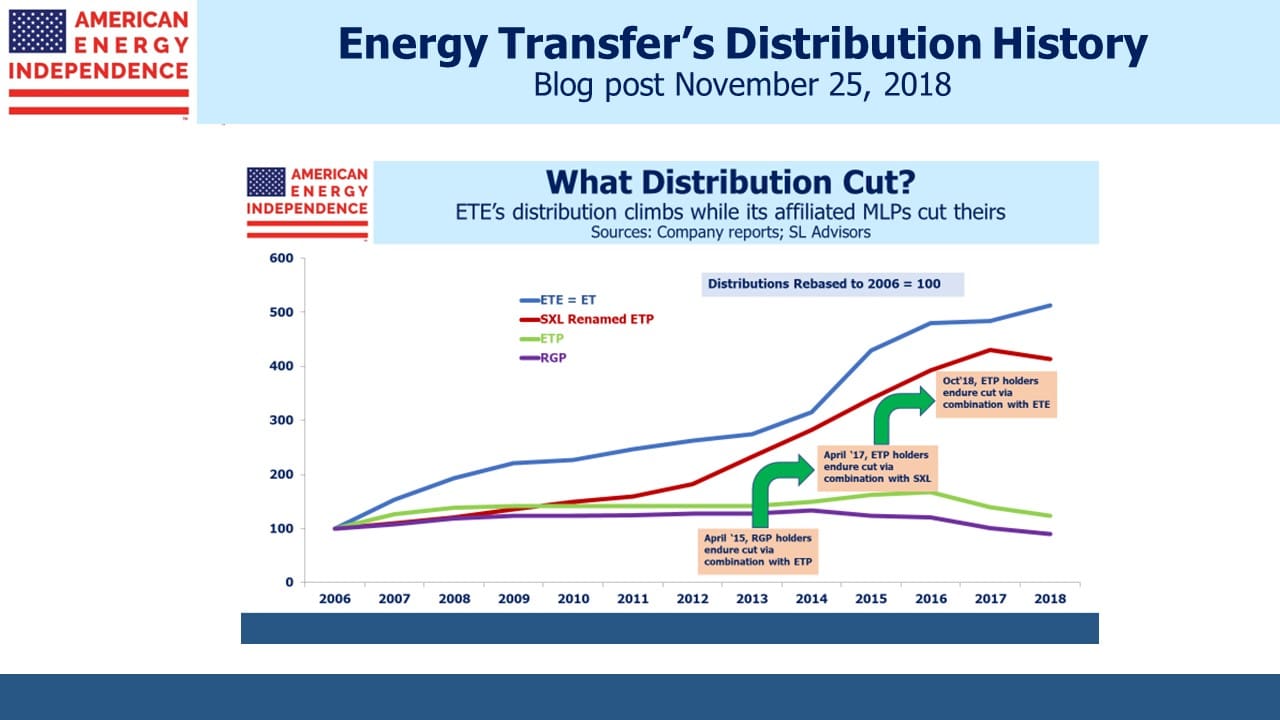

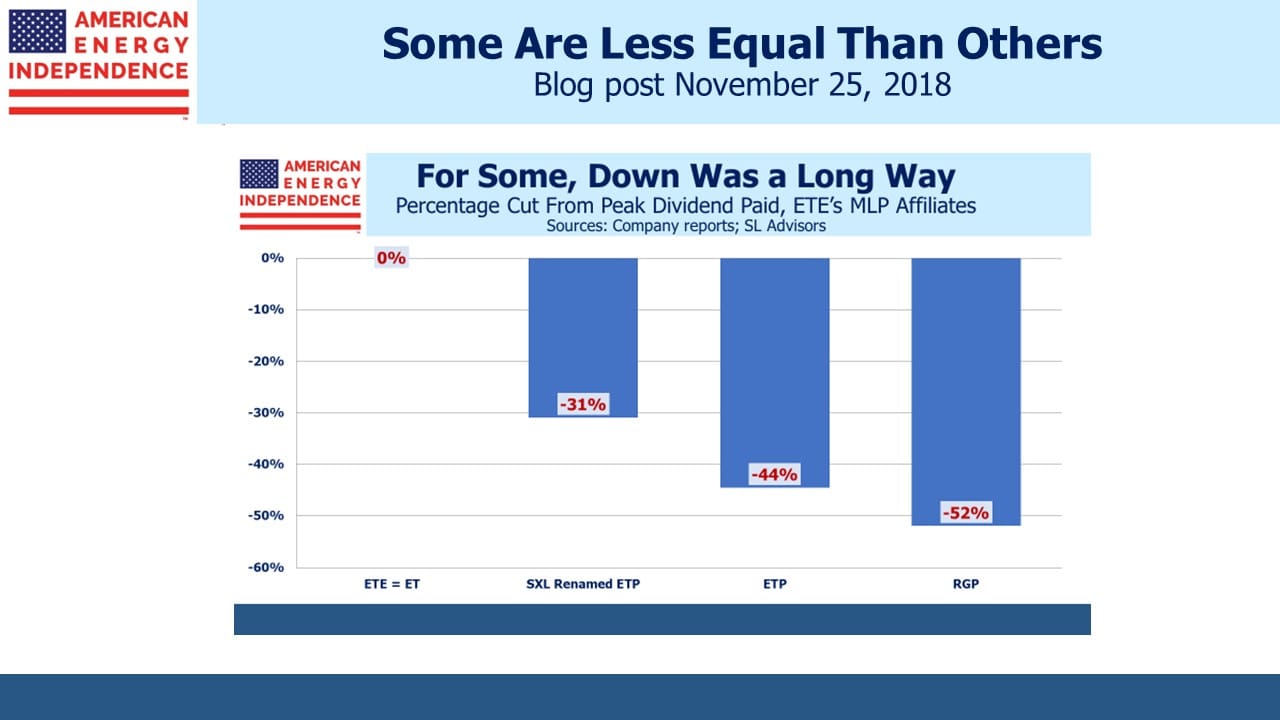

Longtime MLP investors recall the “toll-model” by which pipeline businesses were described. During times of extreme turmoil such as the Covid collapse of March 2020, the implied promise of stability was conspicuously absent to say the least. But the price recovery since then has been accompanied by improved risk metrics that are making the comparison with other long-lived infrastructure more relevant.

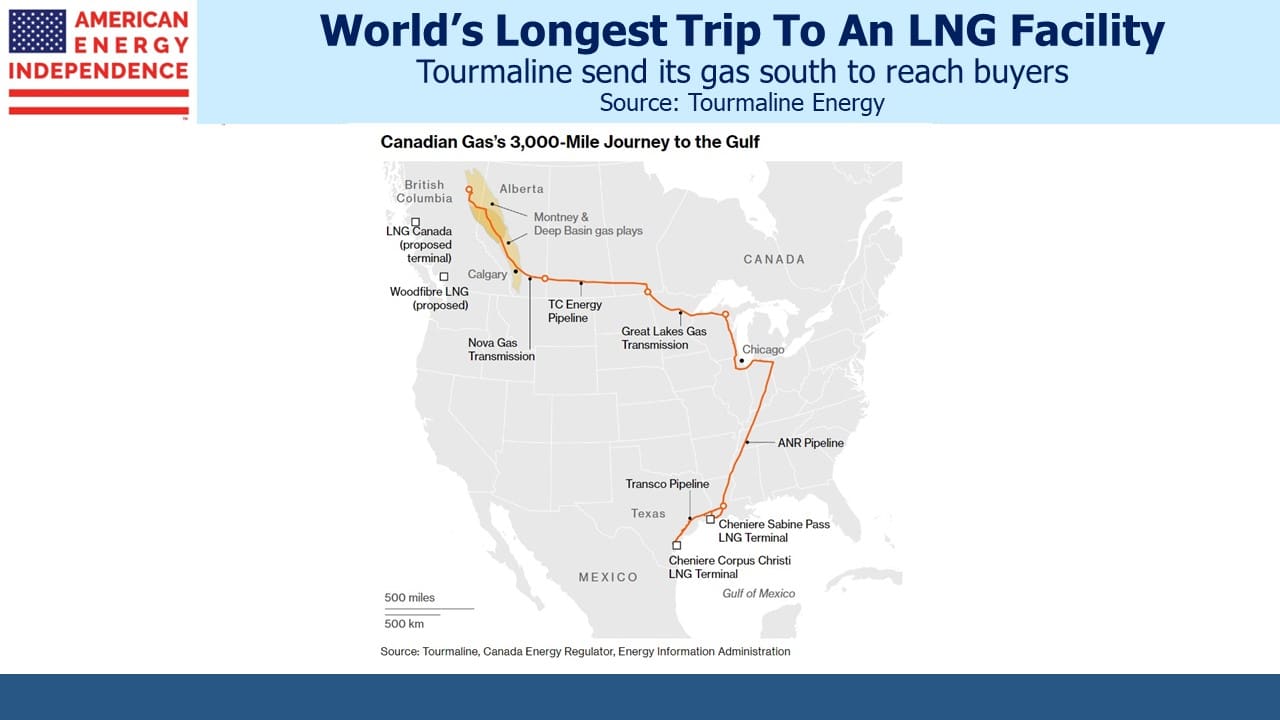

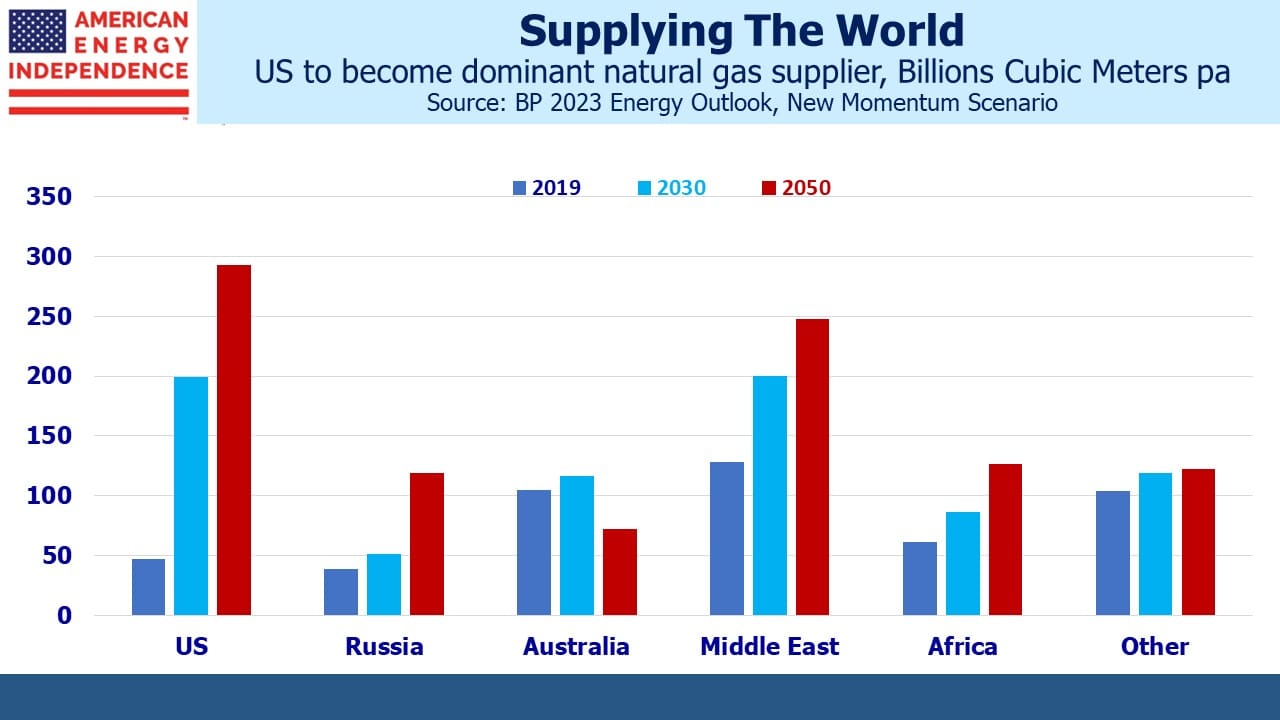

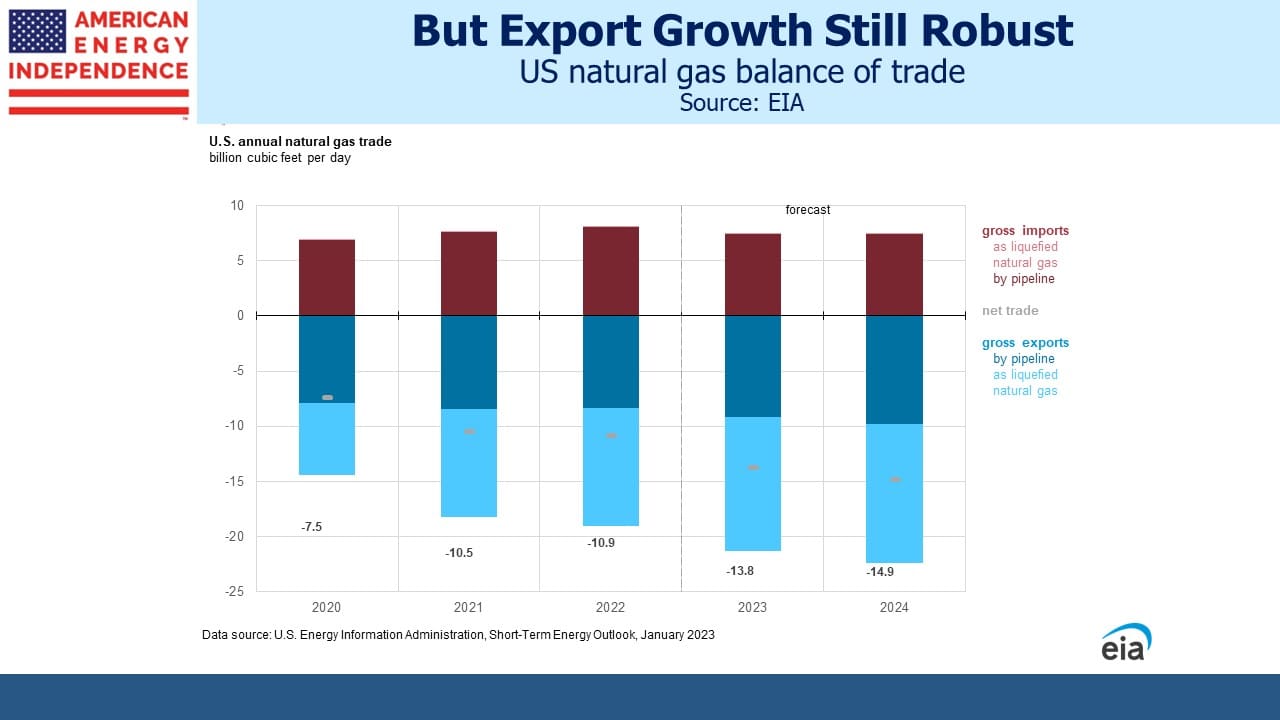

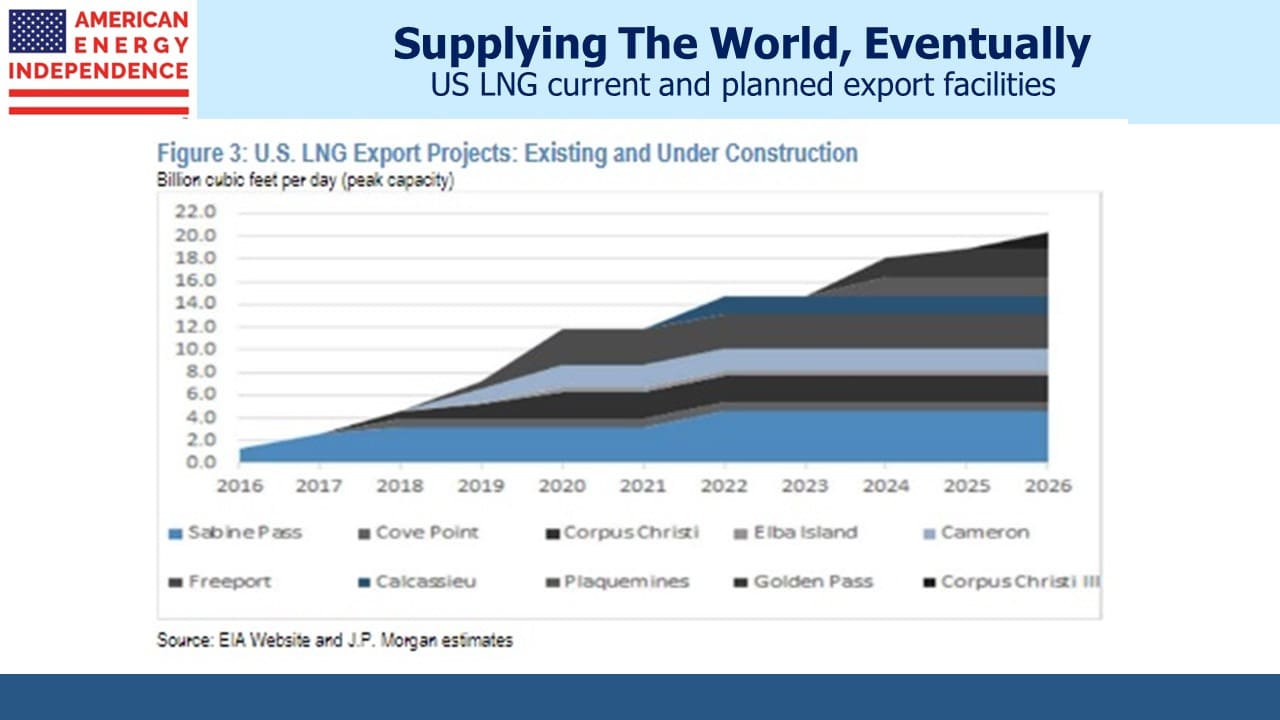

Cheniere provided an example of longevity on Thursday when they announced plans to sharply increase capacity at their Sabine Pass LNG plant. This expansion will increase export capacity by 74% and is planned to be in service by the end of the decade.

On the company’s 4Q22 earnings call, CEO Jack Fusco added, “Over the next few decades, both the supply and demand side are supportive of new liquefaction infrastructure.” (emphasis added).

This sounds more like the outlook of a company that owns and runs hard assets with visible long-term cashflows.

What’s true for LNG exports must also be true for the pipelines and related infrastructure that moves the natural gas from America’s interior to its coast. Enbridge, Energy Transfer, Enterprise Products, Kinder Morgan, Williams Companies and others are also in the long-lived infrastructure business with cash flow stability, earnings visibility and multi-year contracts.

Balance sheet risk has been declining (see Pipelines Grow Into Lower Risk). Debt:EBITDA below 4.0X is the norm for investment grade companies. 3.5X is common, and Enterprise Products finished the year at 2.9X, below their recently revised 3.0X target.

Capital is being returned to shareholders in the form of dividend growth and buybacks, further cementing the lower capex trajectory.

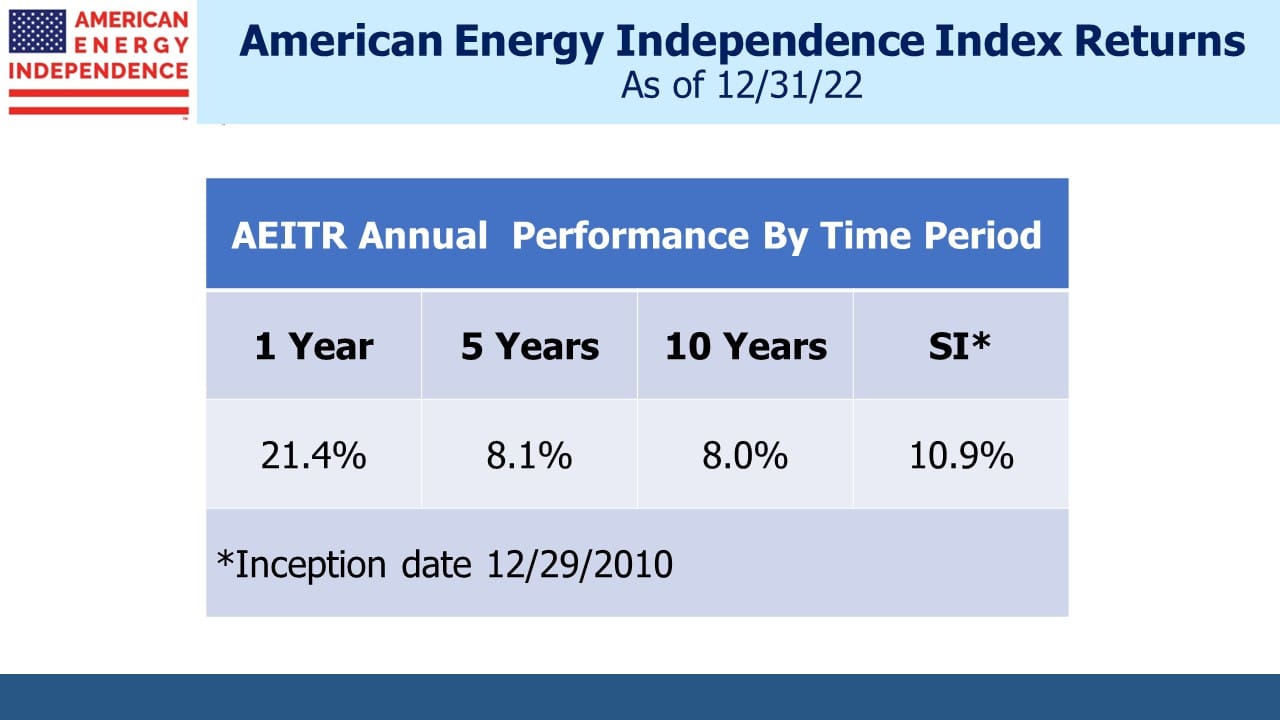

A reduced risk profile means less commodity sensitivity (see Energy’s Asynchronous Marriage). Last year crude oil rallied following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine but was weak in the second half of the year, finishing roughly where it started. Unburdened by much correlation with oil, the American Energy Independence Index was up 21.3%.

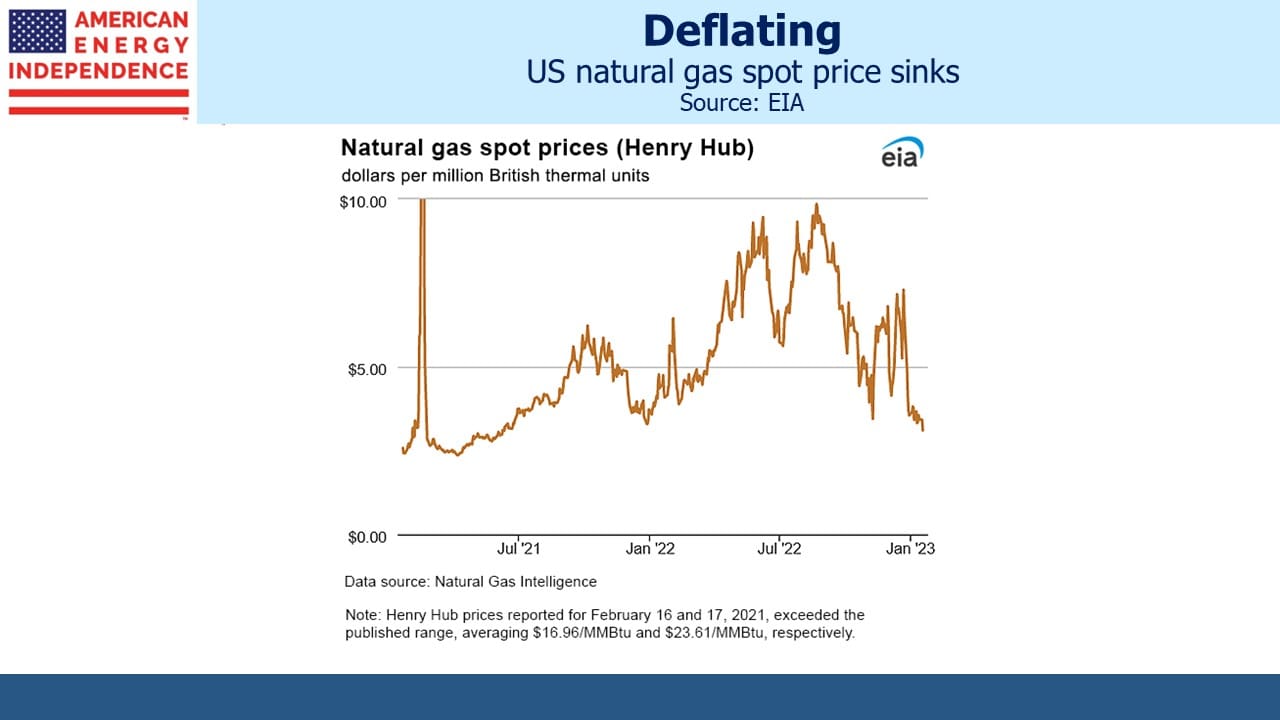

Natural gas prices are near record lows, but infrastructure stocks are immune to that too. This uncoupling from the products they move is allowing investors to consider the sector’s long-lived assets and contracts.

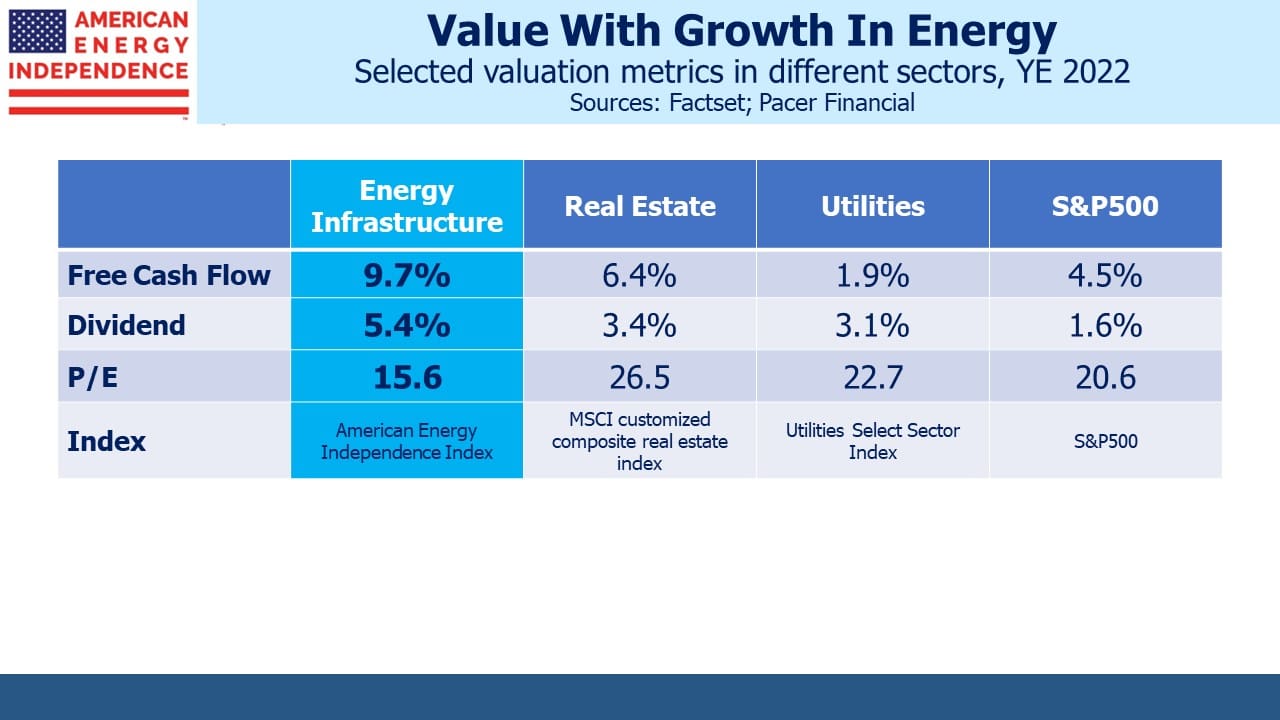

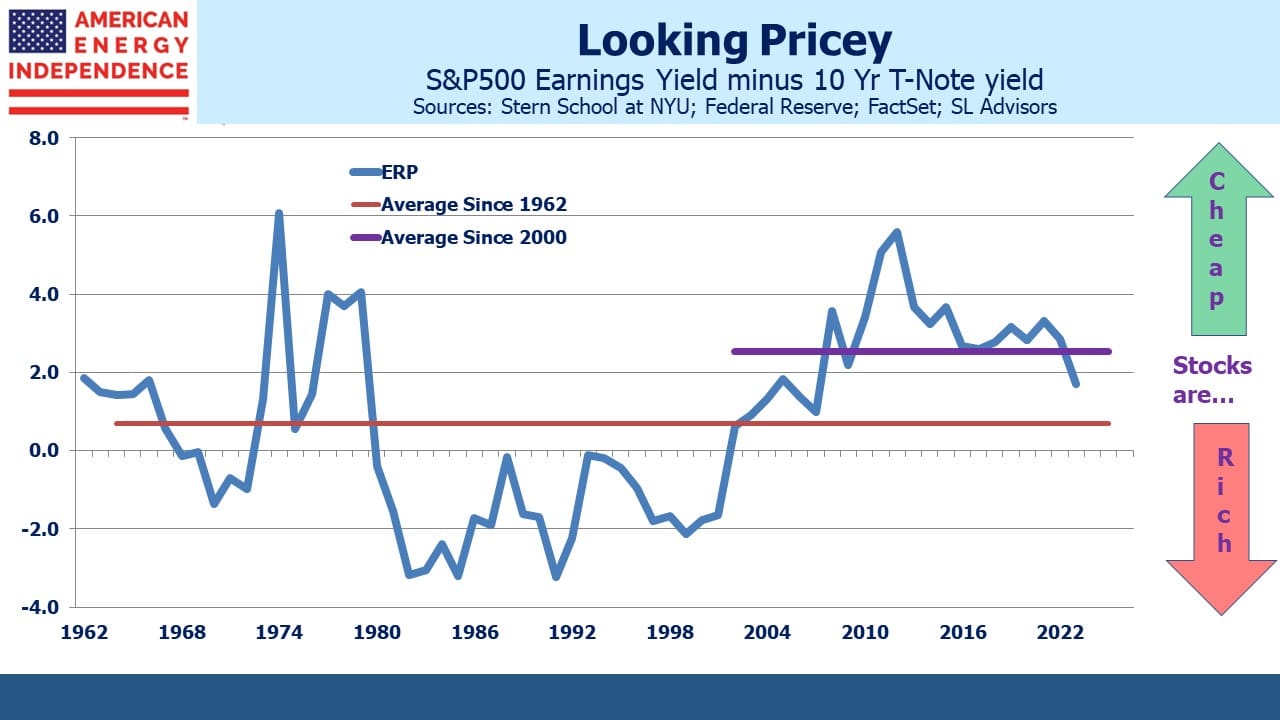

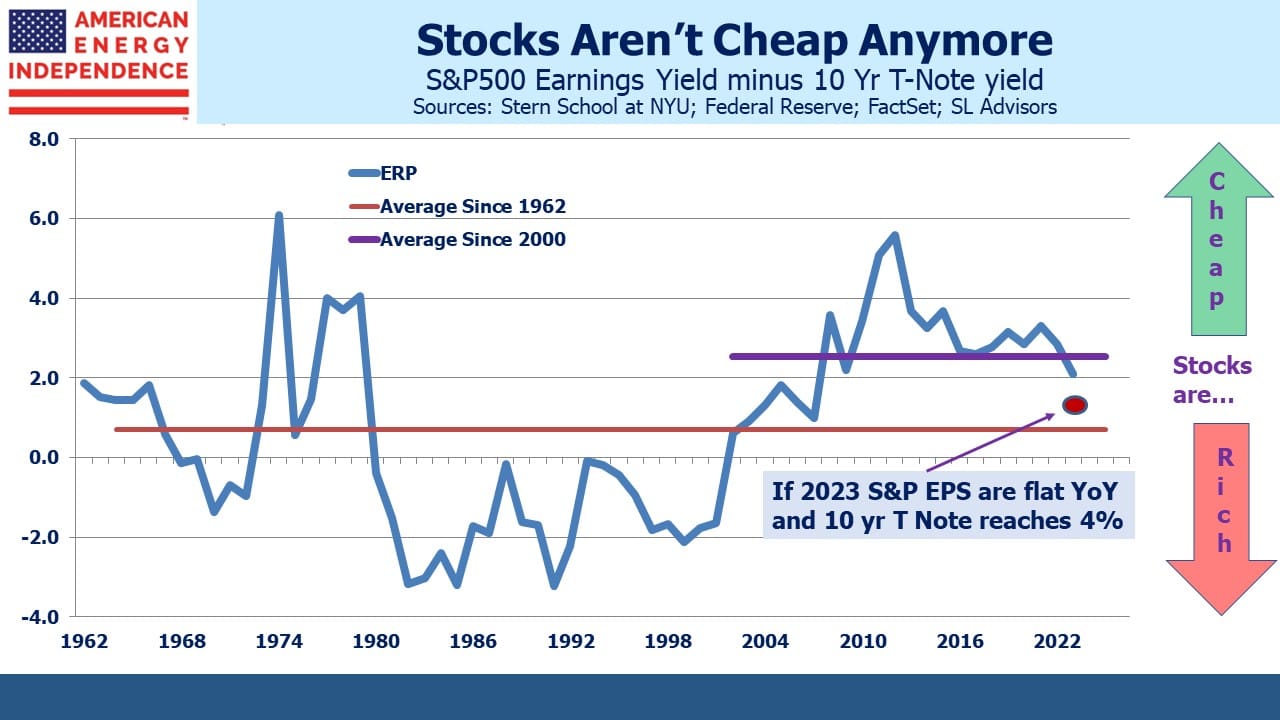

Compared with other infrastructure sectors such as real estate or utilities, energy is attractively priced. Free cash flow yields are half as much again as REITs and 5X utilities. The 5.4% dividend yield is amply covered by cash flow and the P/E ratio also lower than other sectors. Compared to the S&P500, energy infrastructure metrics are substantially better.

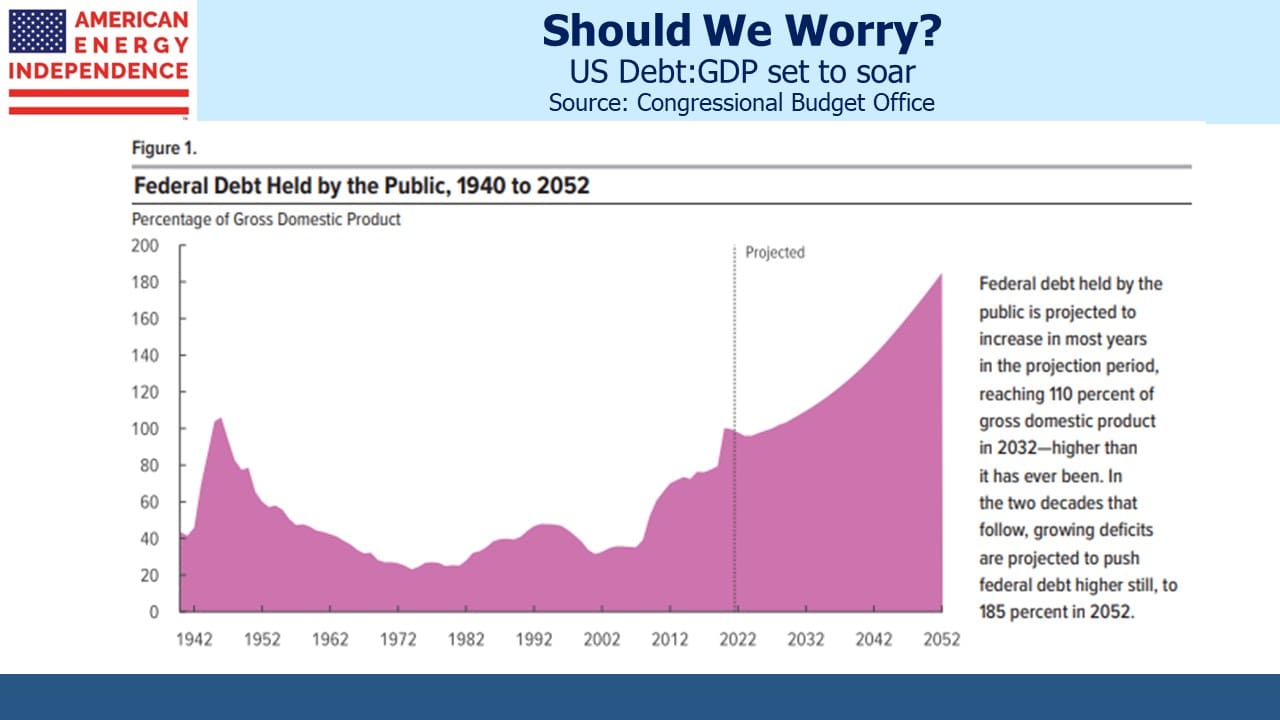

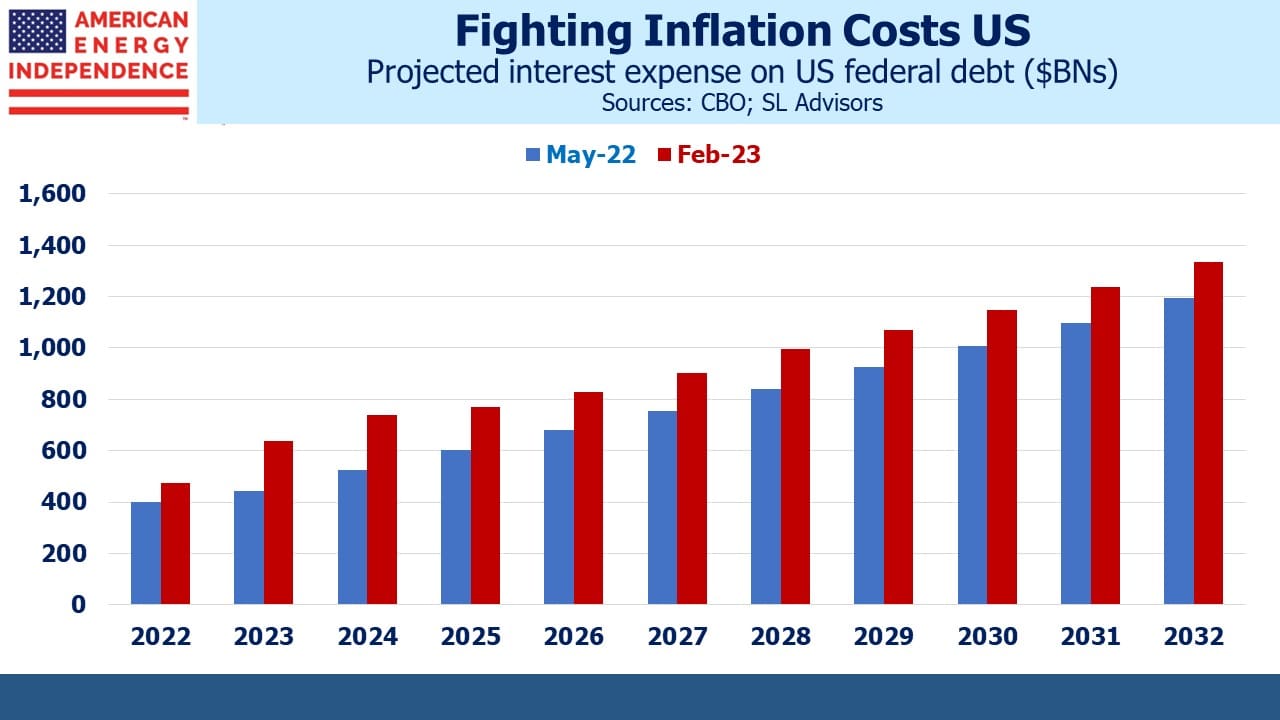

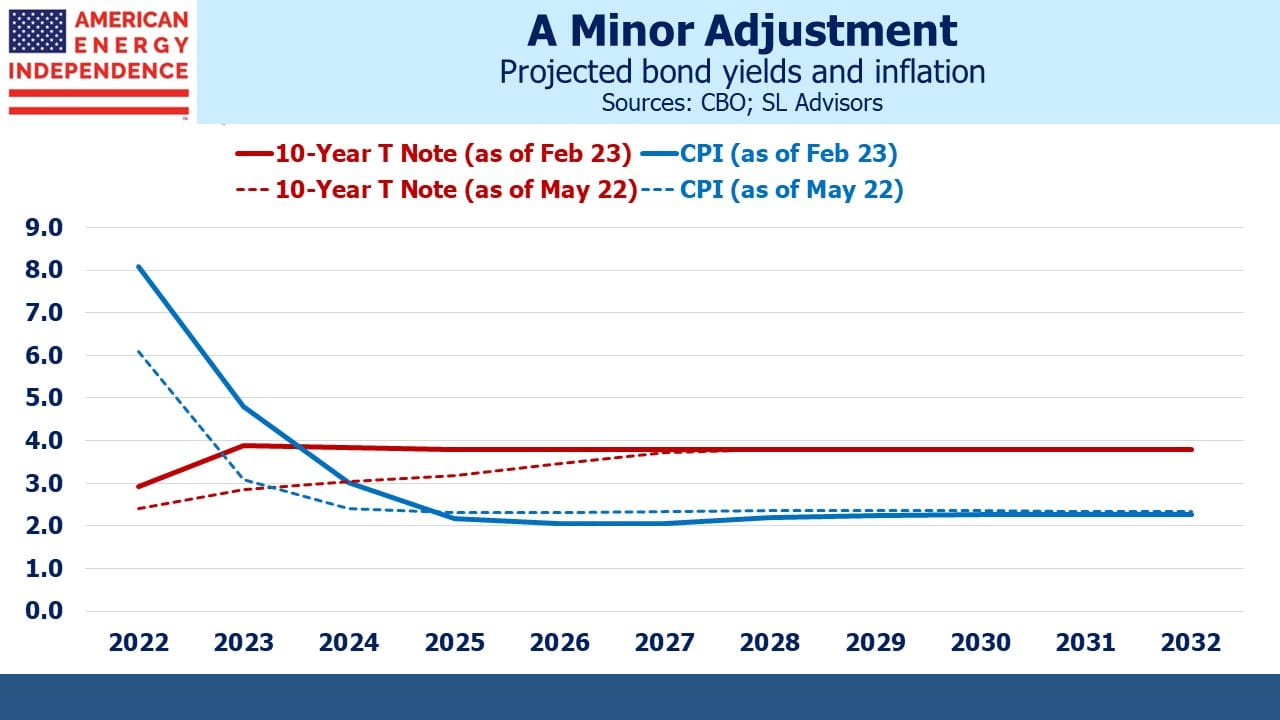

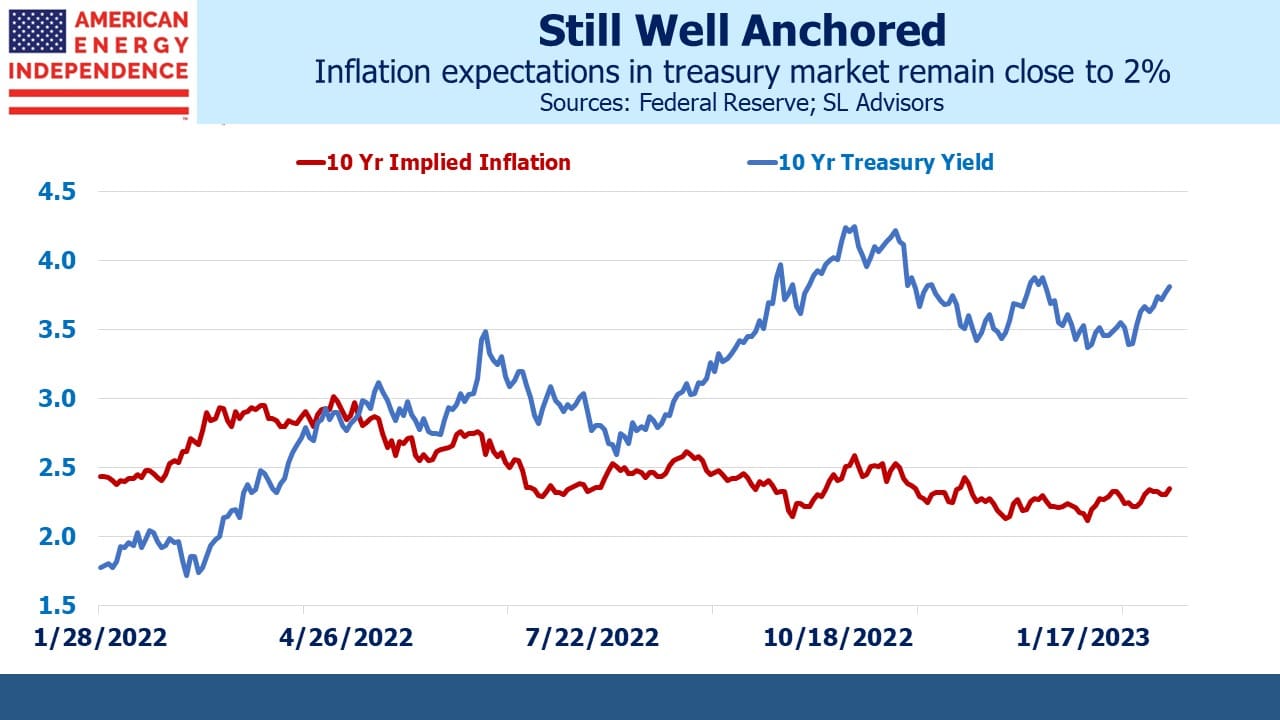

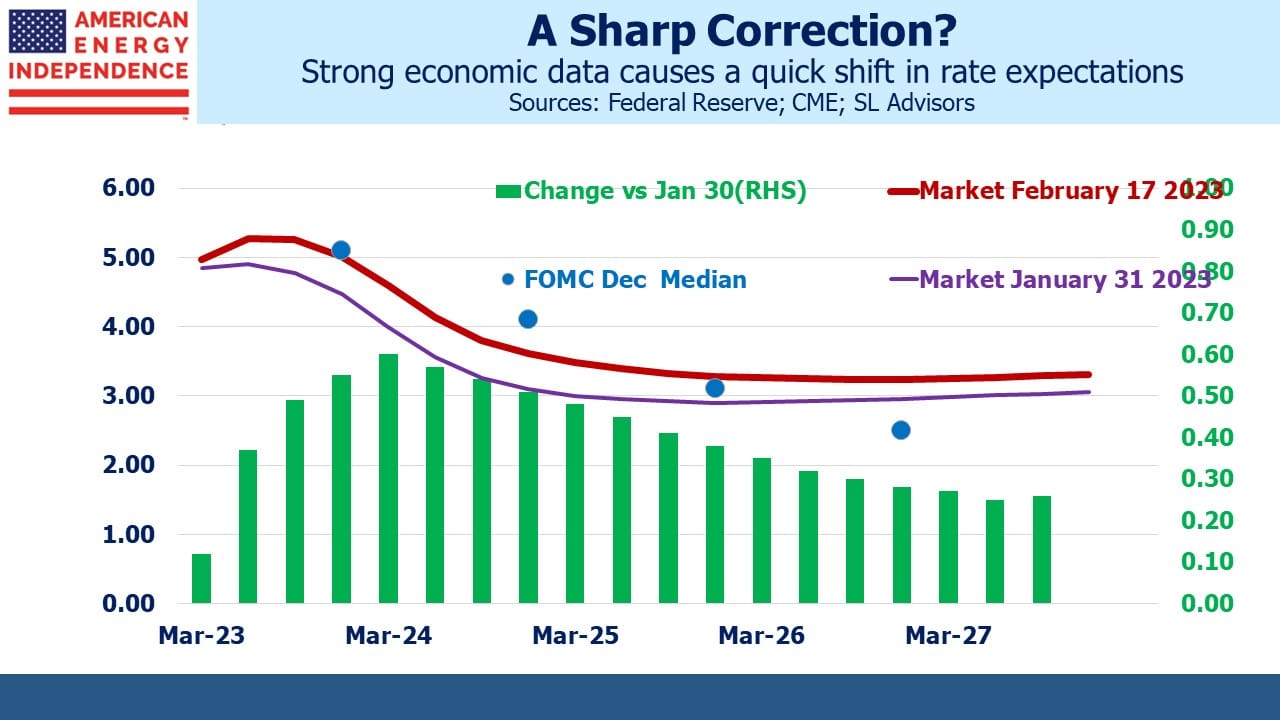

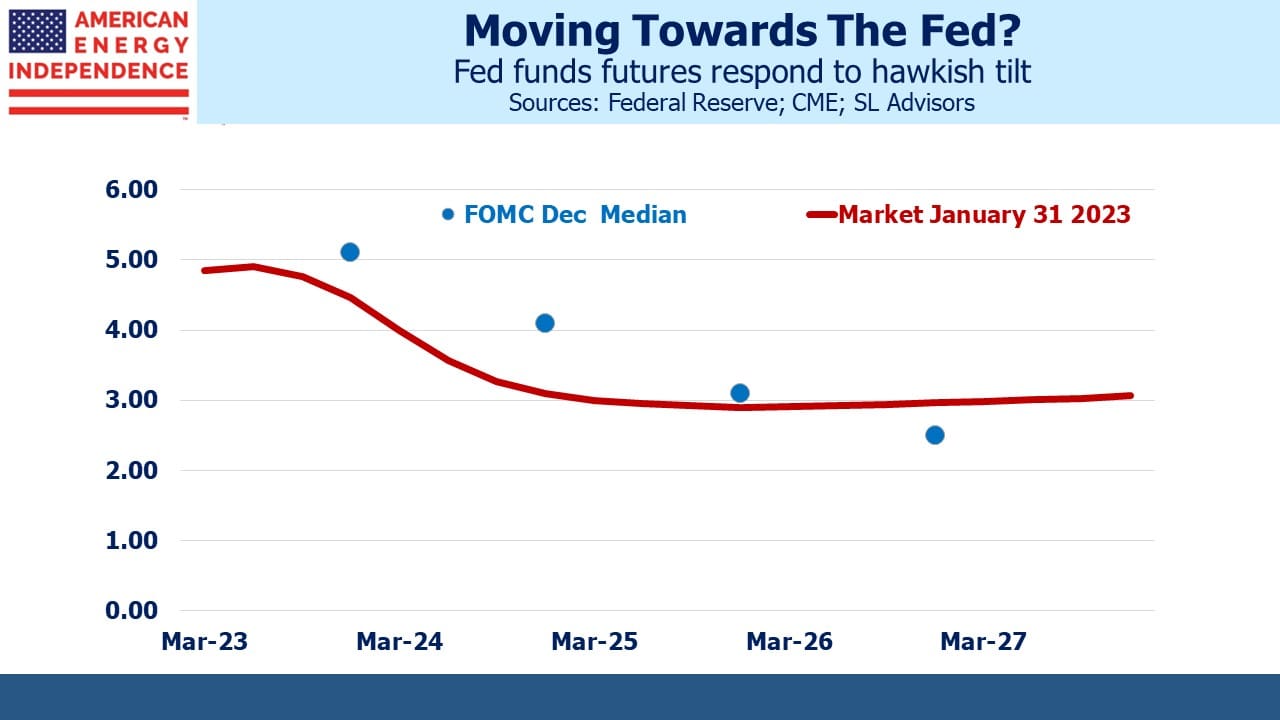

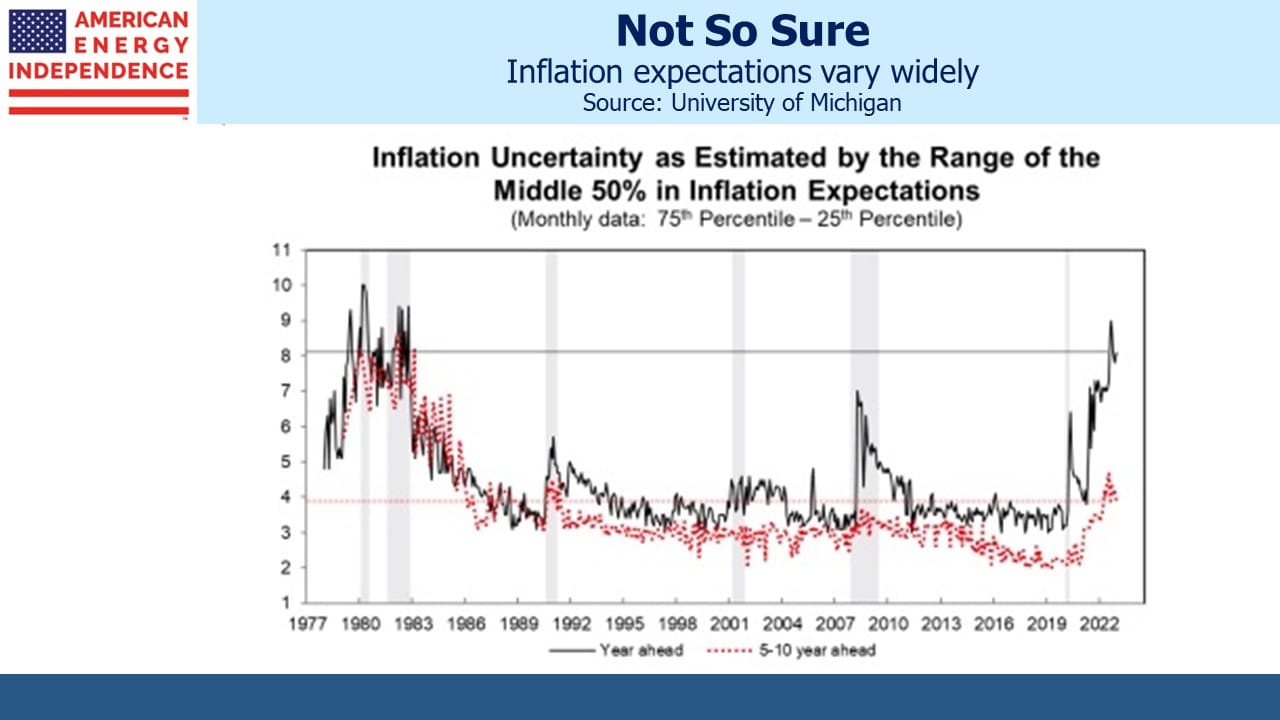

The recent upside surprise on inflation and economic growth also adds to the appeal of energy infrastructure where inflation escalators are a common feature of pipeline contracts (see Confronting Asymmetric Risks). Expectations for Fed policy have undergone a rapid change since the employment report.

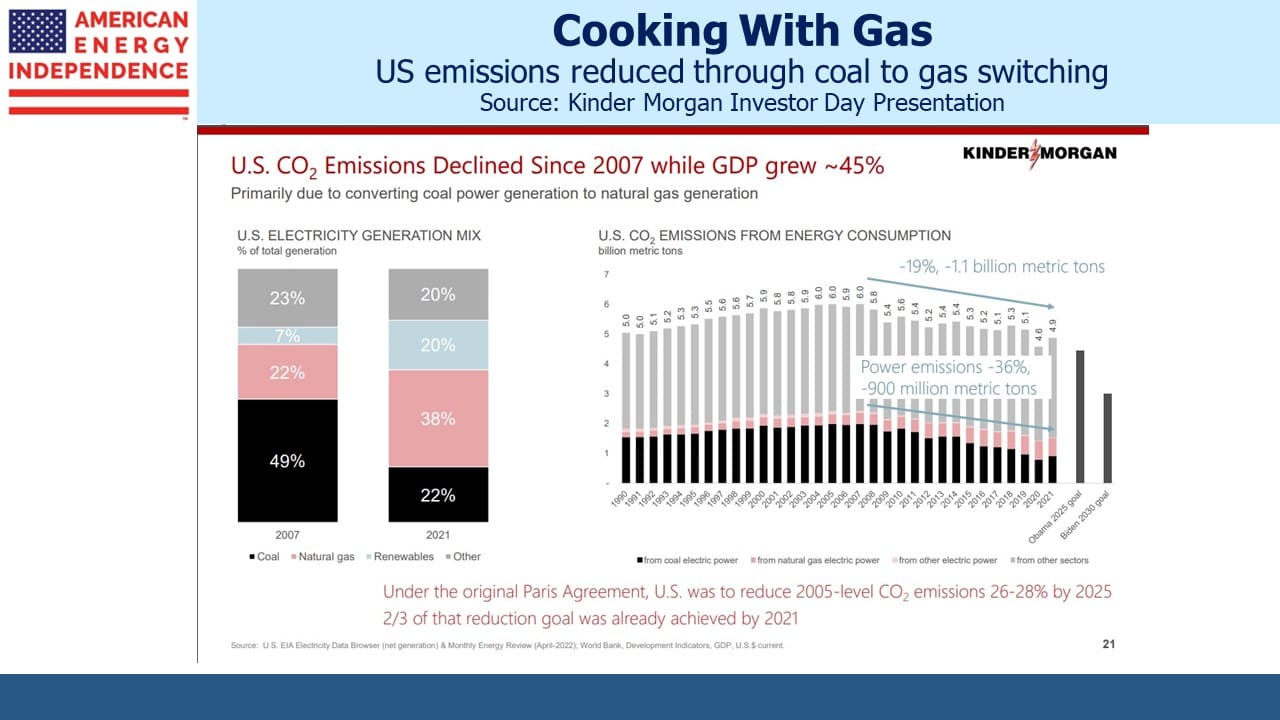

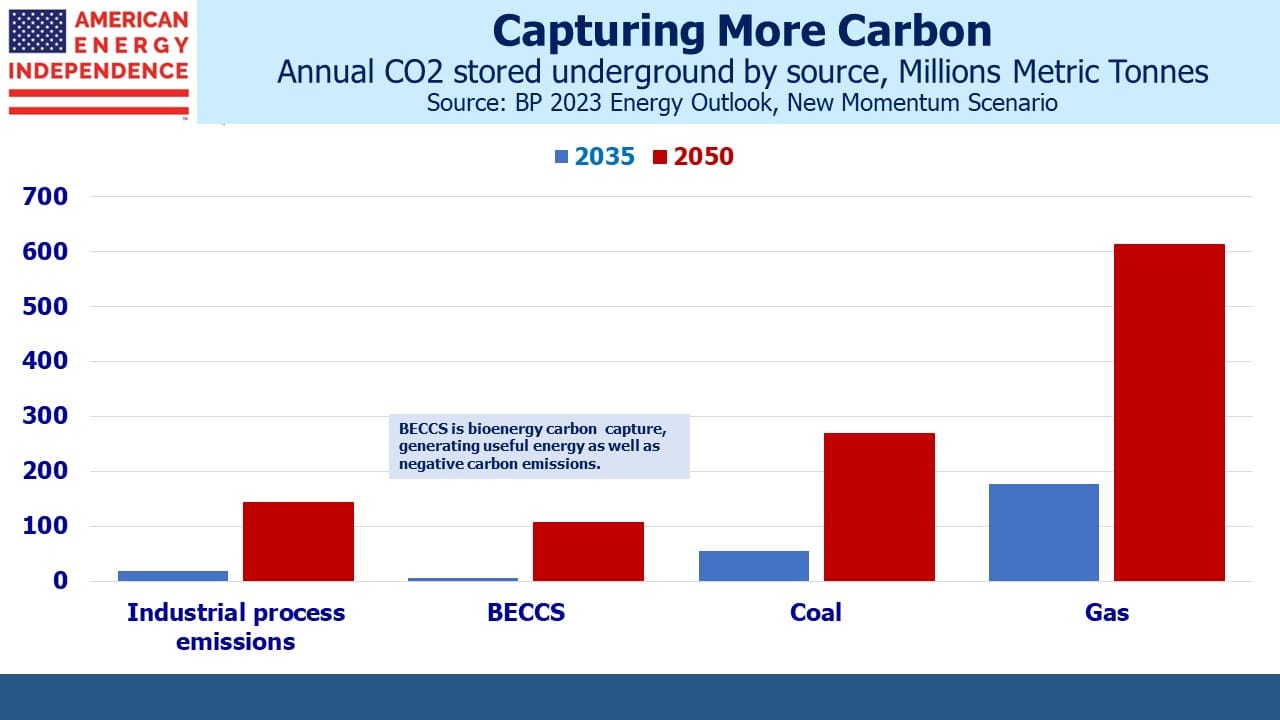

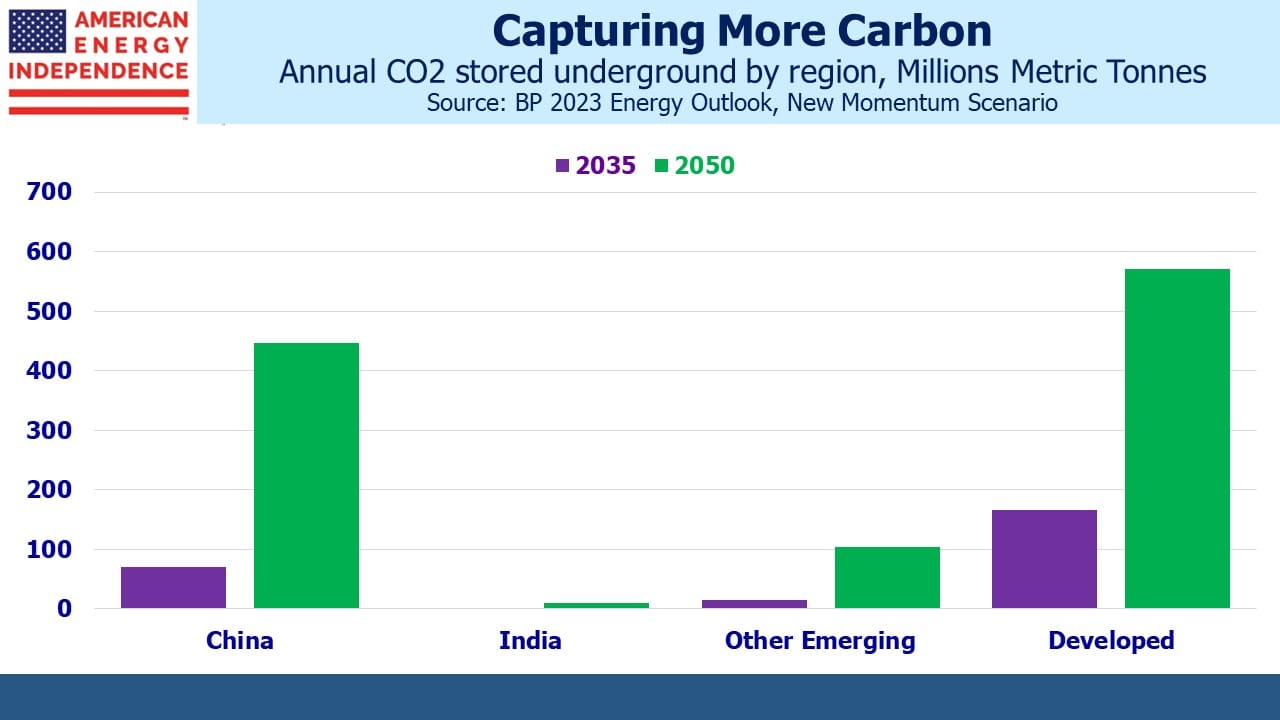

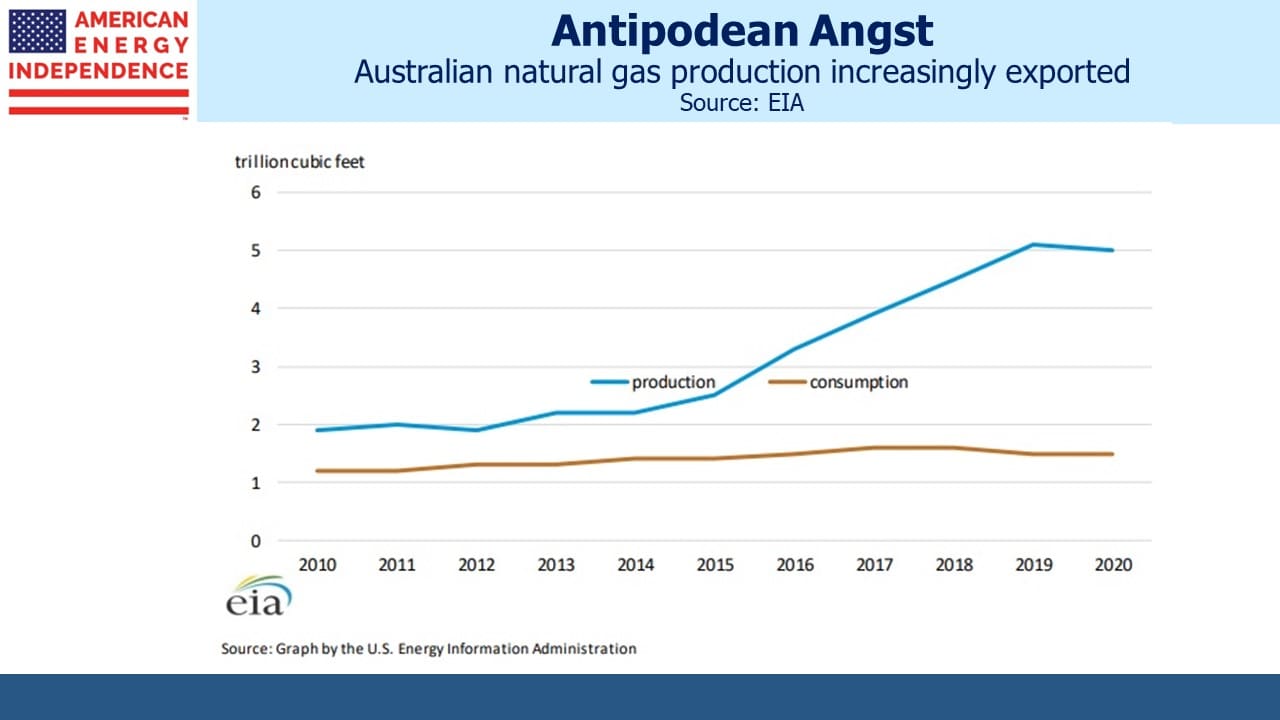

Cheniere and others recognize that cheap US natural gas will be in demand for years, both as a cleaner substitute for coal and to compensate for the intermittency of renewables. Thanks to the Inflation Reduction Act, energy infrastructure will play a vital role in carbon capture and in the development of hydrogen.

For example, Exxon Mobil announced plans to build the world’s biggest “blue” hydrogen facility near Houston. It will extract hydrogen from natural gas, capture the emitted CO2 for sequestration, and convert the resulting hydrogen into ammonia for easier transport in chemical tankers. The new plant is expected to be operational by 2027.

Rather than confronting existential challenges from the energy transition, the sector’s biggest companies are embracing opportunities. Solar and wind garner disproportionate attention. The reliable manufacture of steel, cement, fertilizer and plastic, what author Vaclav Smil calls “the four pillars of civilization”, will continue to rely on fossil fuels. It’s becoming clear that reliable, clean energy needs existing infrastructure companies.

Buyers and sellers of LNG are signing long-term contracts. China Gas Holdings just signed two 20-year agreements with Venture Global.

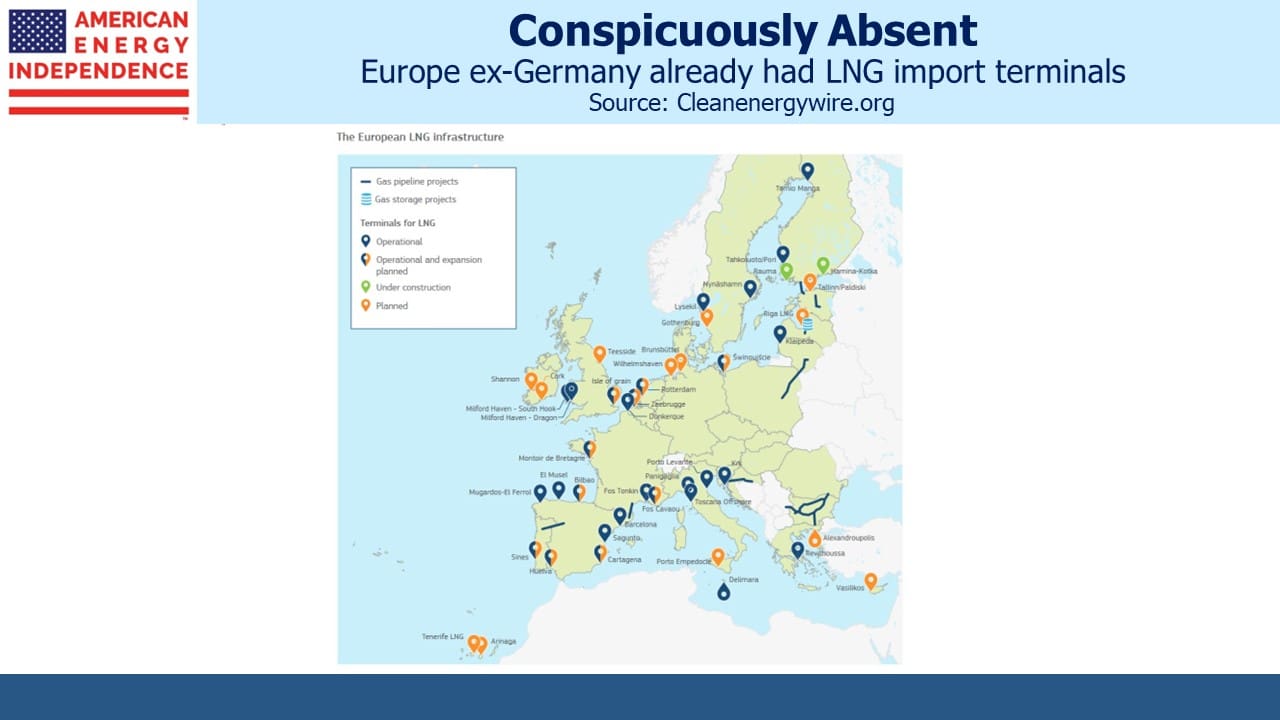

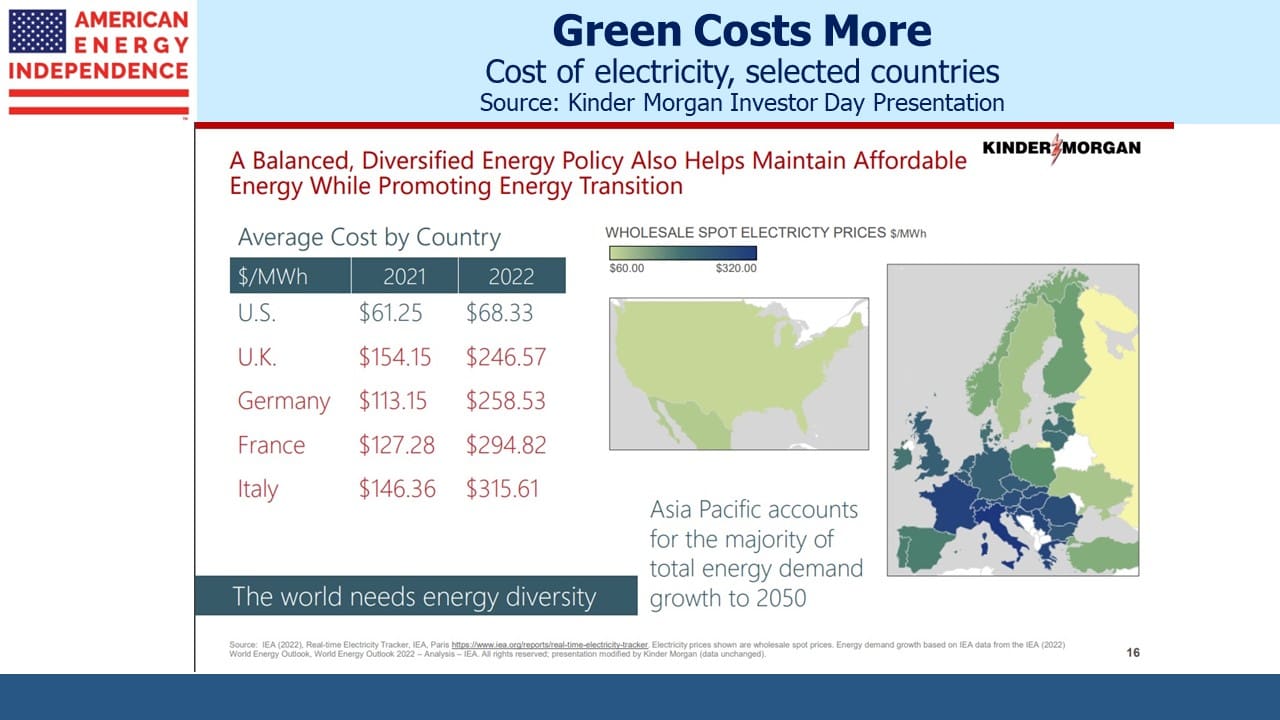

European LNG purchases are set to increase sharply. Germany was the large country most exposed to the loss of Russian pipeline imports last year. Their government now expects to reach 70 million tonnes per year of LNG import capacity by 2030, putting them fourth in the world behind South Korea, China and Japan. Germany has been slower in making long term commitments than Asian buyers, but they’re adding significant capability.

On Thursday BASF provided a reminder of the costs Germany’s past misguided energy policies have imposed by cutting 2,600 jobs due to, “high costs in Europe, uncertainty due to the war in Ukraine and rising interest rates.”

American Energy Infrastructure is well placed to profit.

We have three funds that seek to profit from this environment:

Energy Mutual Fund Energy ETF Real Assets Fund