Will Kinder Morgan Cover Its Cost Of Capital?

Kinder Morgan (KMI) reported earnings last week and announced that President Kim Dang will be taking over from Steve Kean as CEO. This prompted us to look back over KMI’s history, which reflects some of the best and worst of the MLP sector for the past ten years.

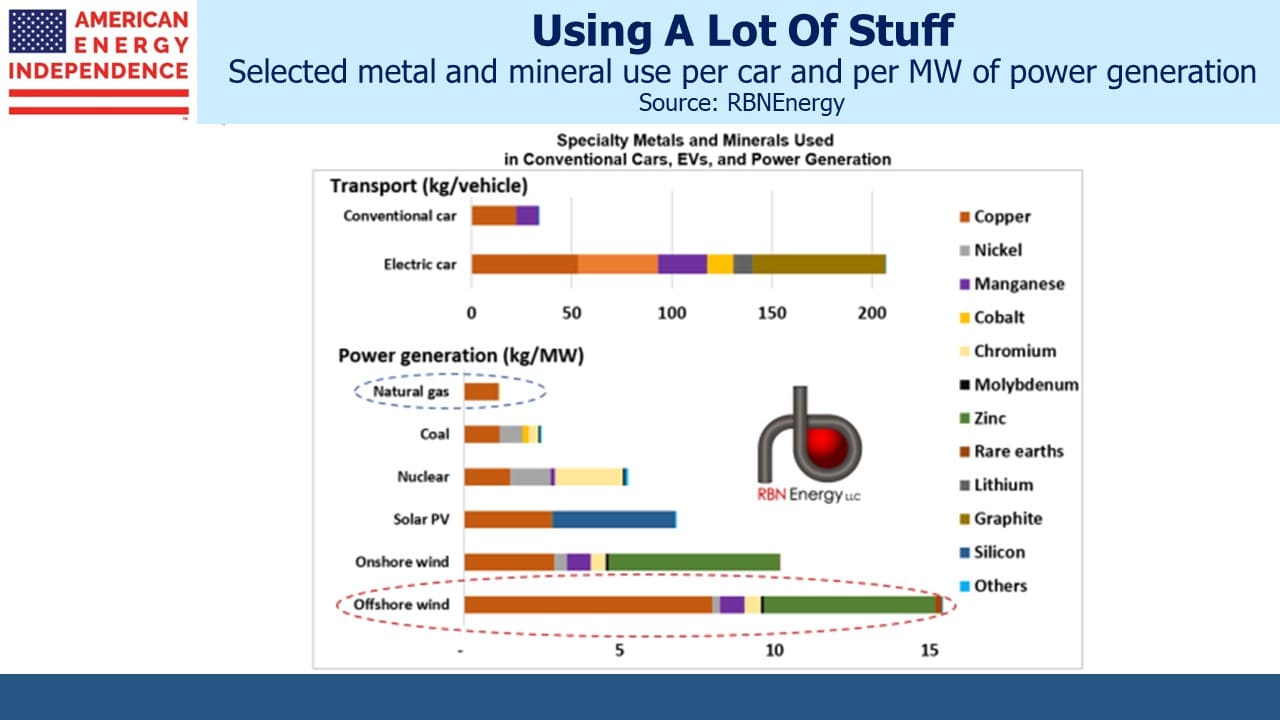

A decade ago the shale revolution drove increased capex for upstream E&P companies as well as the midstream ones that service them. Prior to 2014 KMI operated as the General Partner (GP) to MLPs Kinder Morgan Partners (KMP) and El Paso Partners (EP). The GP-MLP structure always looked to us like the hedge fund manager-hedge fund relationship.

The GP (HF manager) calls the shots and the MLP (HF) does what it’s told with limited rights for the limited partners. The GP could and often did sell assets to its MLP (a “dropdown”), directing the MLP to issue equity and debt to pay for them. Or the GP could direct the MLP to build new infrastructure. The GP had Incentive Distribution Rights (IDRs) which operated like the carried interest taken by HF or private equity managers. It gave them a share of the profits with minimum capital at risk.

Back then we always invested in the GP rather than the MLP because, as with hedge fund managers, that’s where the big money gets made. Rich Kinder exploited his MLPs masterfully and became a billionaire in the process. However, by 2014 the increasing need of MLPs to raise ever more capital to finance infrastructure for the shale revolution was driving up yields, making raising equity capital more expensive.

Kinder was frustrated at KMP’s high cost of capital, so in August 2014 Kinder Morgan announced it was simplifying its structure and rolling its MLPs into KMI to create one single entity. We were moved to write enthusiastically about it (see Valuing Kinder Morgan in its New Structure).

Rich Kinder said at the time, “”We have vastly simplified the structure” and promised “modest cost synergies,” He also promised a $2 annual dividend growing at 10% for the next five years. Less than two years later it was slashed by 75% and still hasn’t recovered.

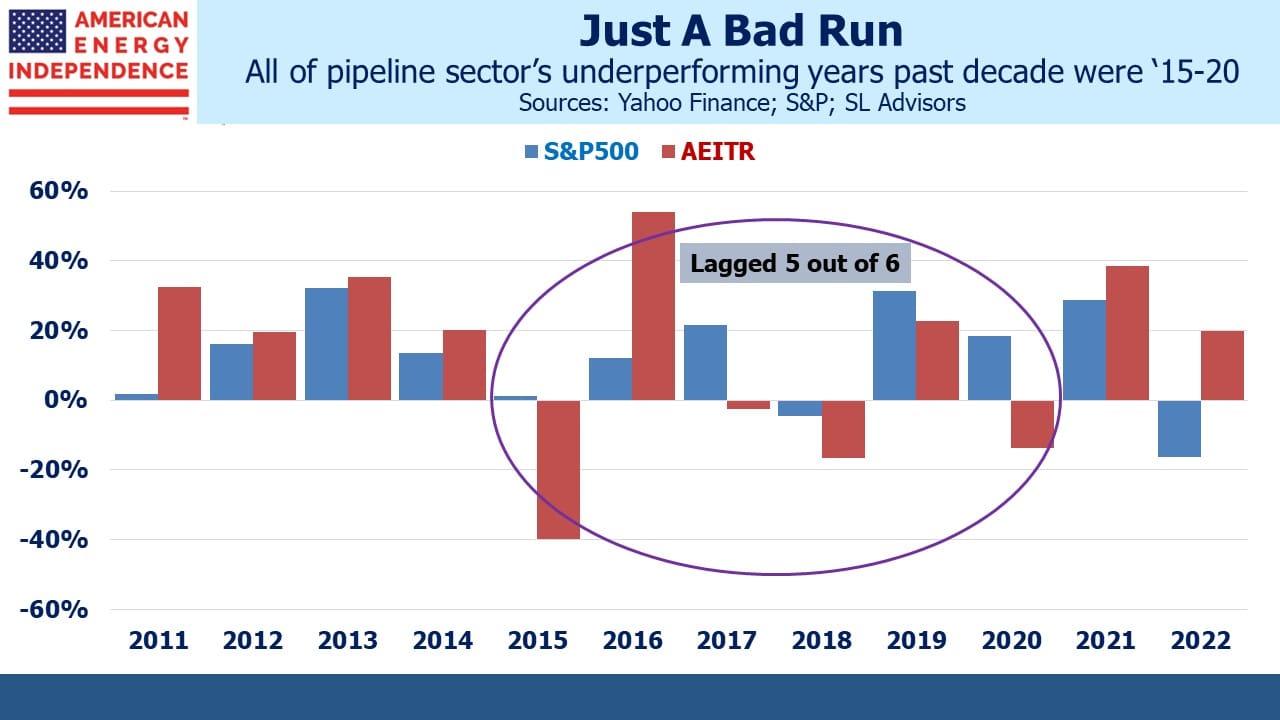

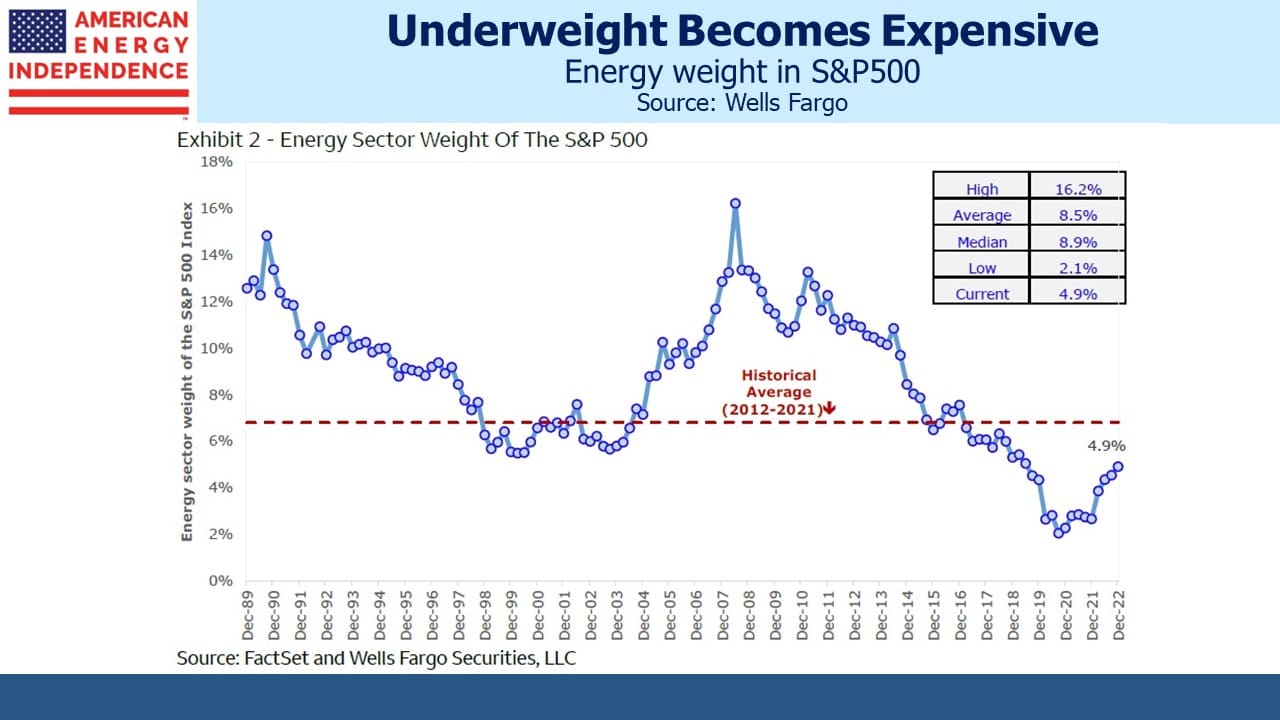

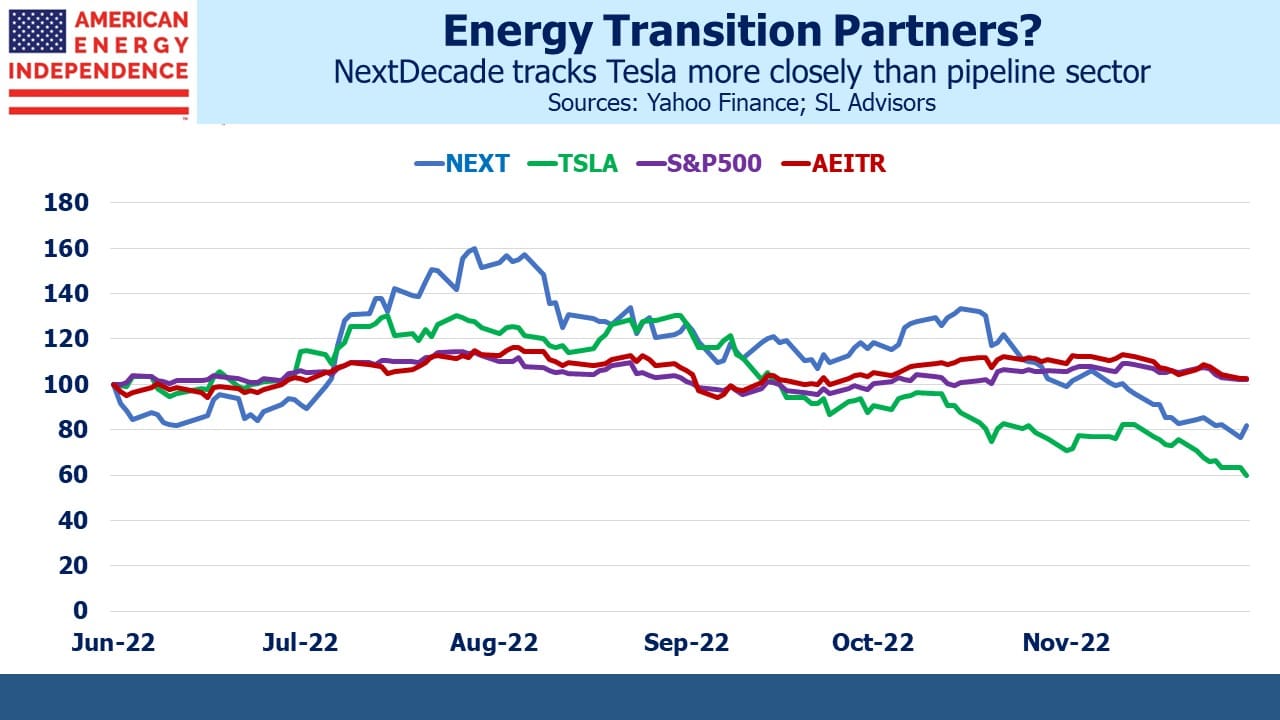

KMI began a trend to roll MLPs up into their GP parent, which was often a corporation. MLPs had attracted income-seeking, K-1 tolerant investors but the model broke when midstream companies followed their upstream clients into over-investing. Increased leverage led to distribution cuts, alienating the traditional income-seeking investor. The MLP structure has never recovered, and they now represent around a third of the sector. The Alerian MLP ETF remains as an anachronistic vehicle for those who only want MLP exposure and are content with a tax-inefficient structure (see AMLP Trips Up On Tax Complexity).

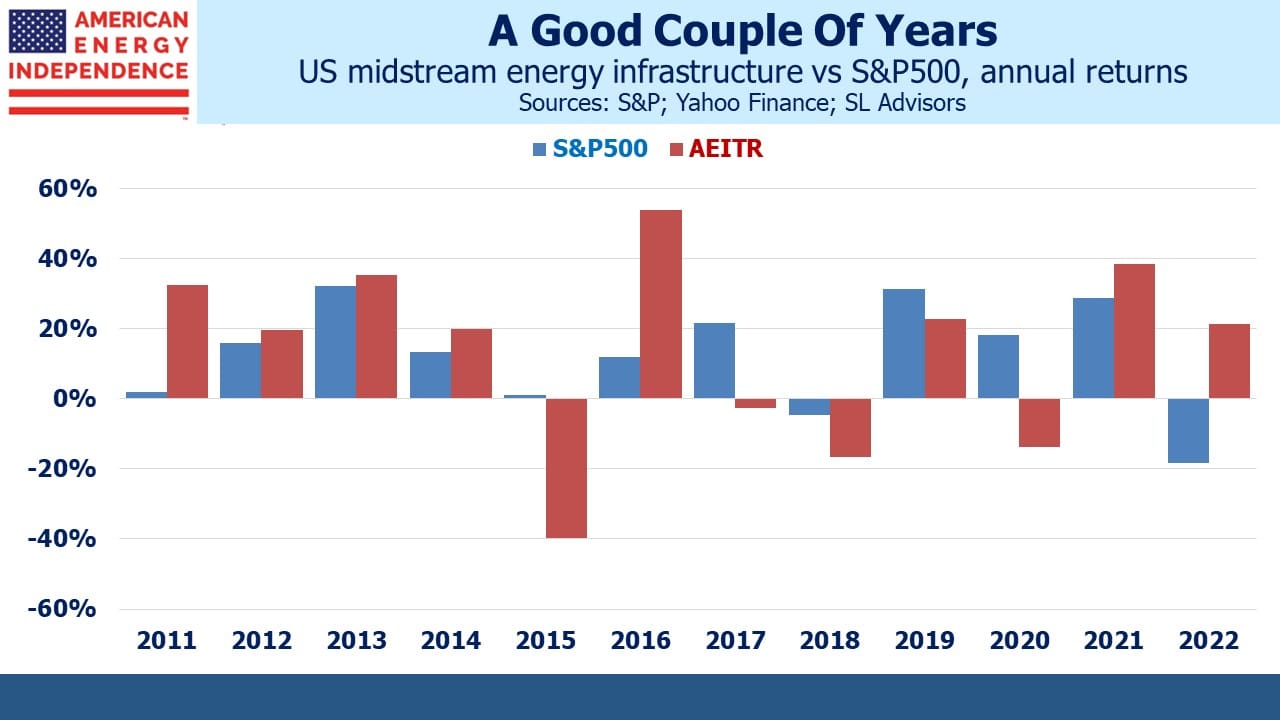

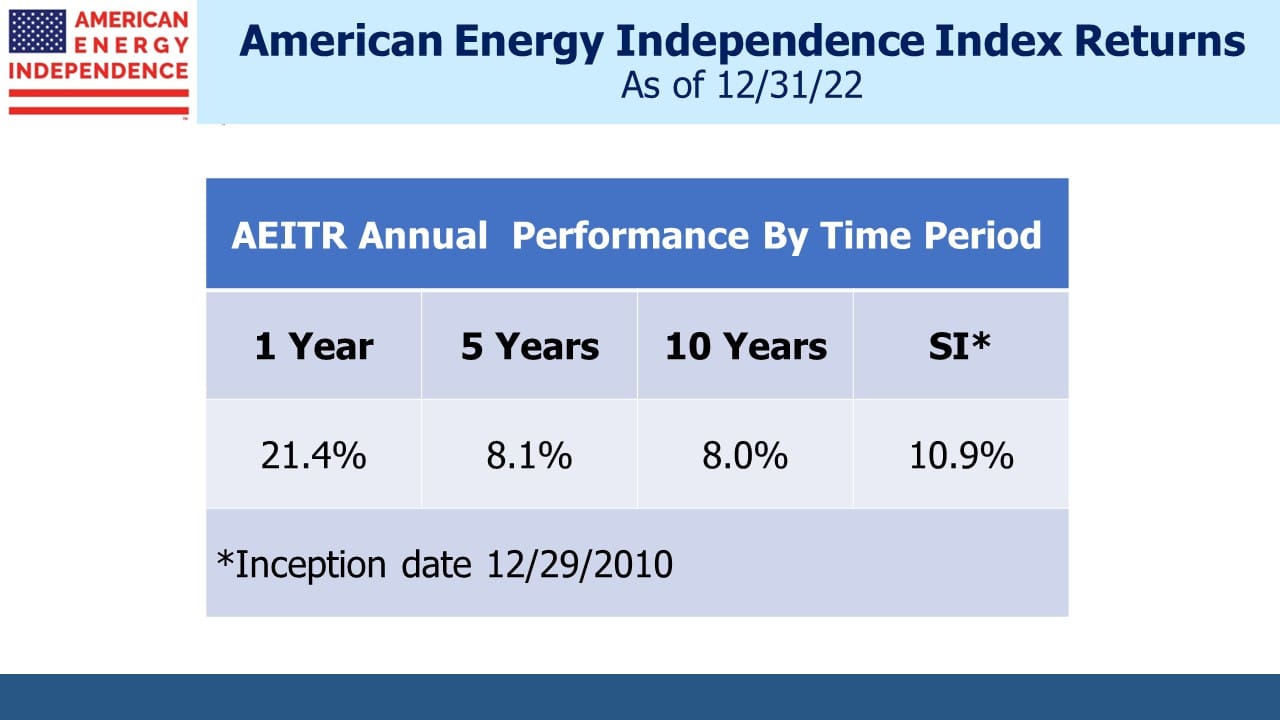

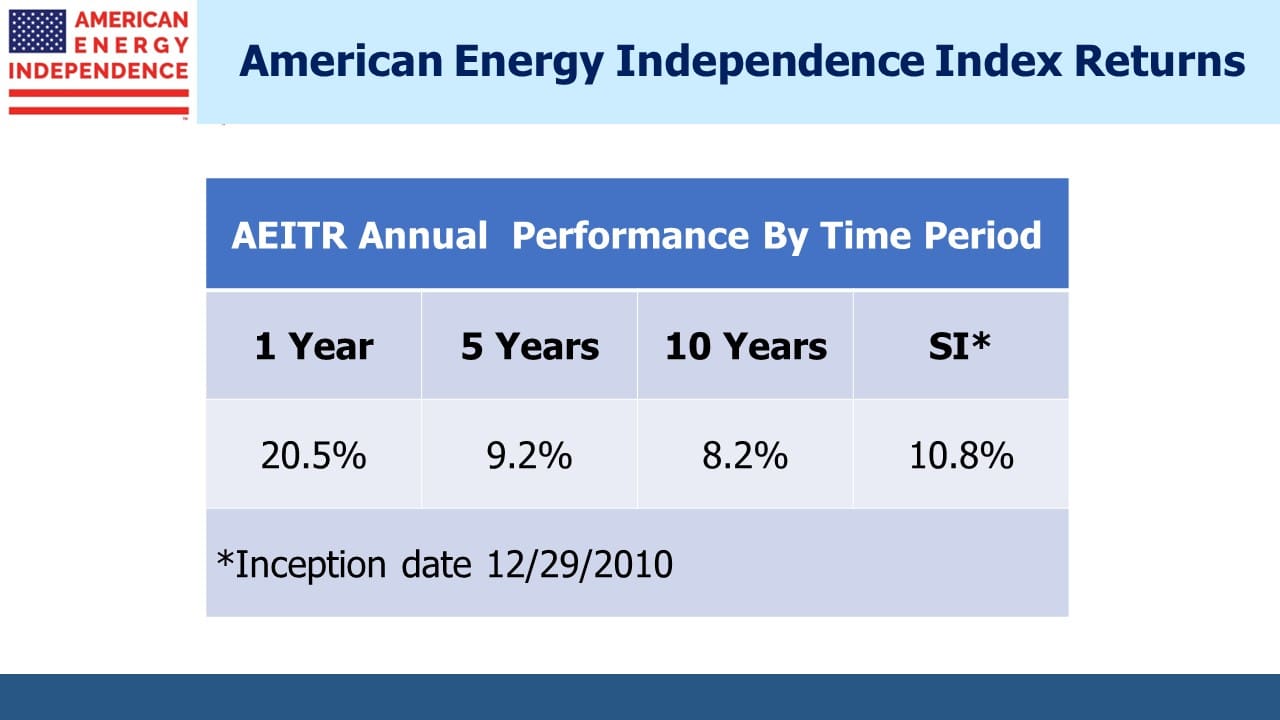

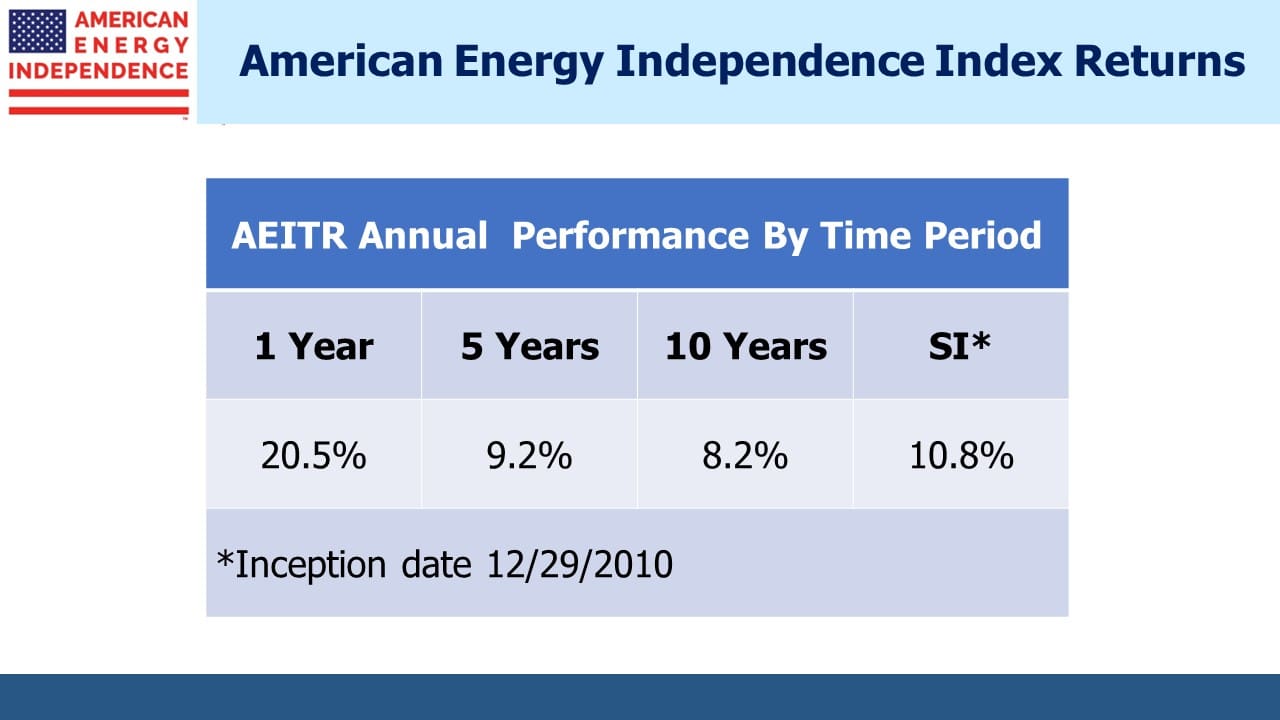

August 2014 was the peak in the energy sector for that cycle. Since then, KMI has generated a minus 2.9% annual return with dividends, lagging the sector, defined as the American Energy Independence Index (AEITR), which has generated 3.3% pa. KMI’s dividend is $1.11, still a long way from the $2 promised nine years ago.

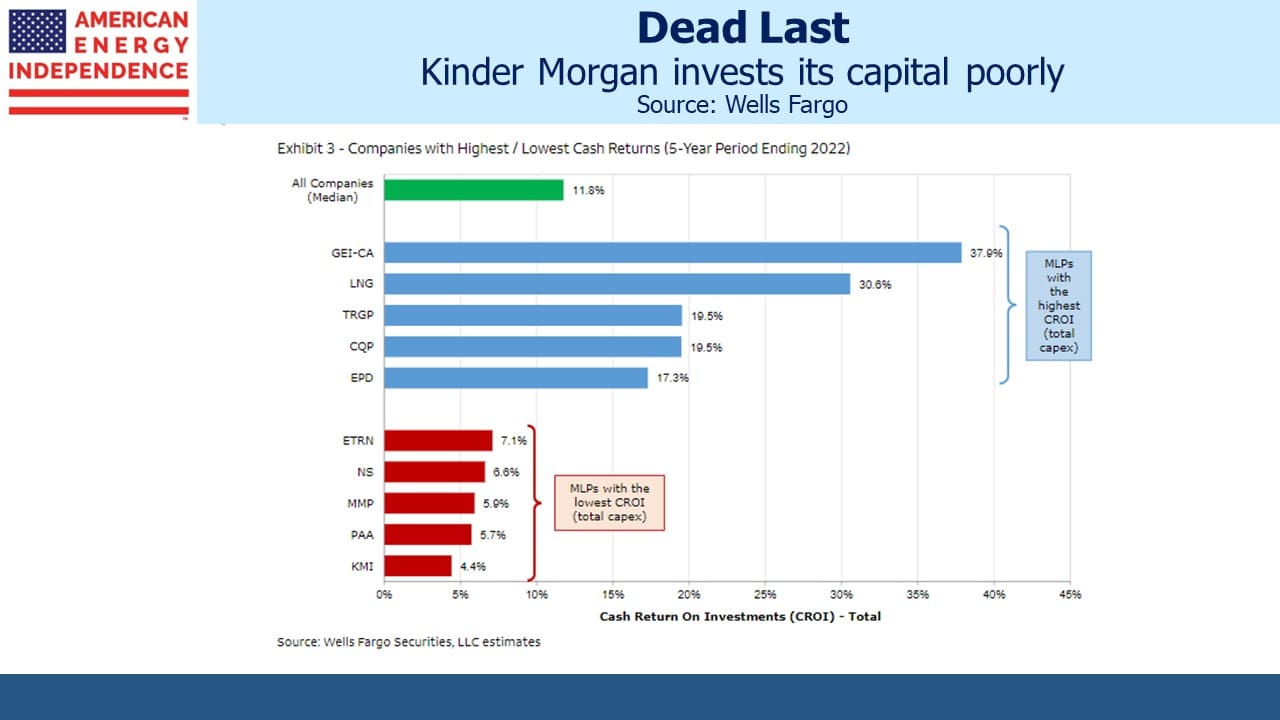

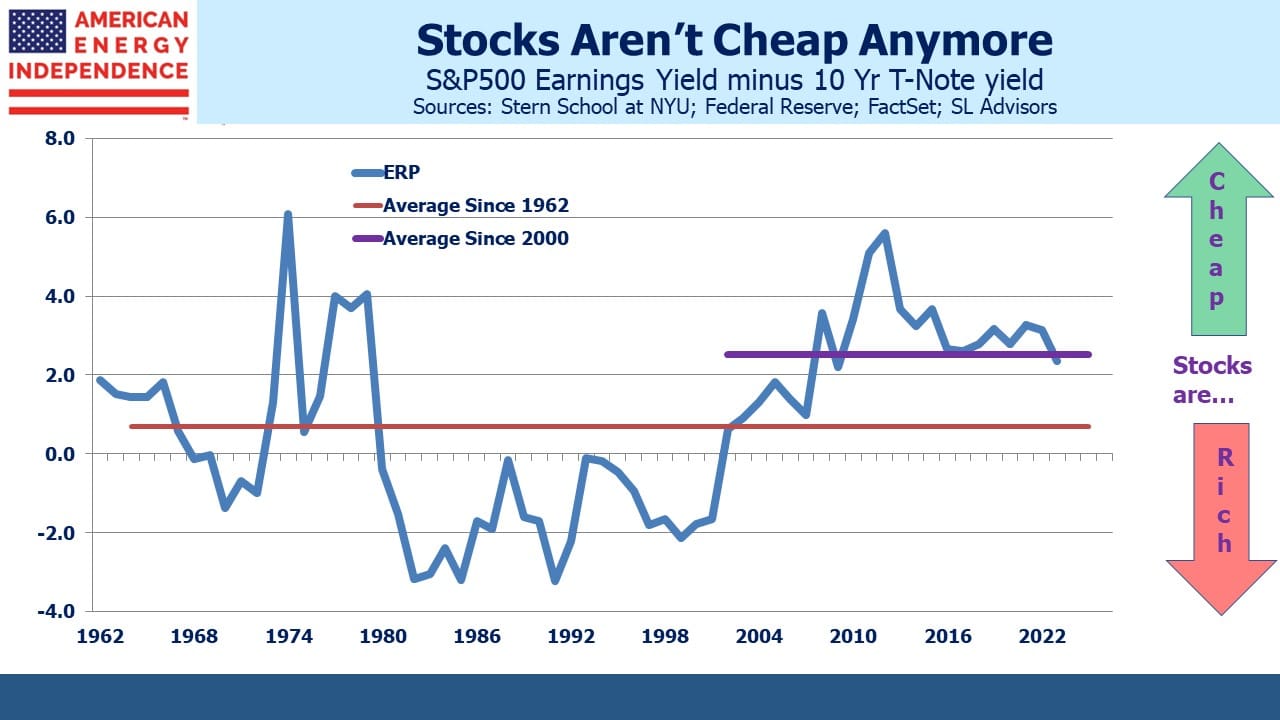

KMI has a track record of investing in low return projects. Wells Fargo calculates that over the past five years KMI has earned a Cash Return On Investment (CROI) of only 4.4%, the lowest of any big company. Since 1999 they’ve earned 5.6% versus an industry median of 10.7%. KMI’s stock has lagged because they keep investing in projects that earn less than their cost of capital.

Rich Kinder ran the company during most of this period, and he’s misallocated his own capital as well as his investors’ because he’s still the biggest individual owner of KMI shares with around 11% of the company. His personal fortune is from understanding how to exploit the GP/MLP structure that used to exist, but he must think it’s from making good investments.

Which brings us to the new CEO Kim Dang. She became CFO in 2011 and has been part of the management team ever since. The low CROI projects substantially occurred on her watch. Did she internally oppose misdirected capital, or did she misestimate returns as much as Kinder? Neither explanation is good, and KMI’s pliant board of directors doesn’t seem too concerned about the company’s investment track record.

On KMI’s 4Q22 earnings call, Dang commented that, “A large part of my job is going to be about continuity.” Long-time investors may feel a twinge of nervousness at this prospect. An improvement on past performance is needed.

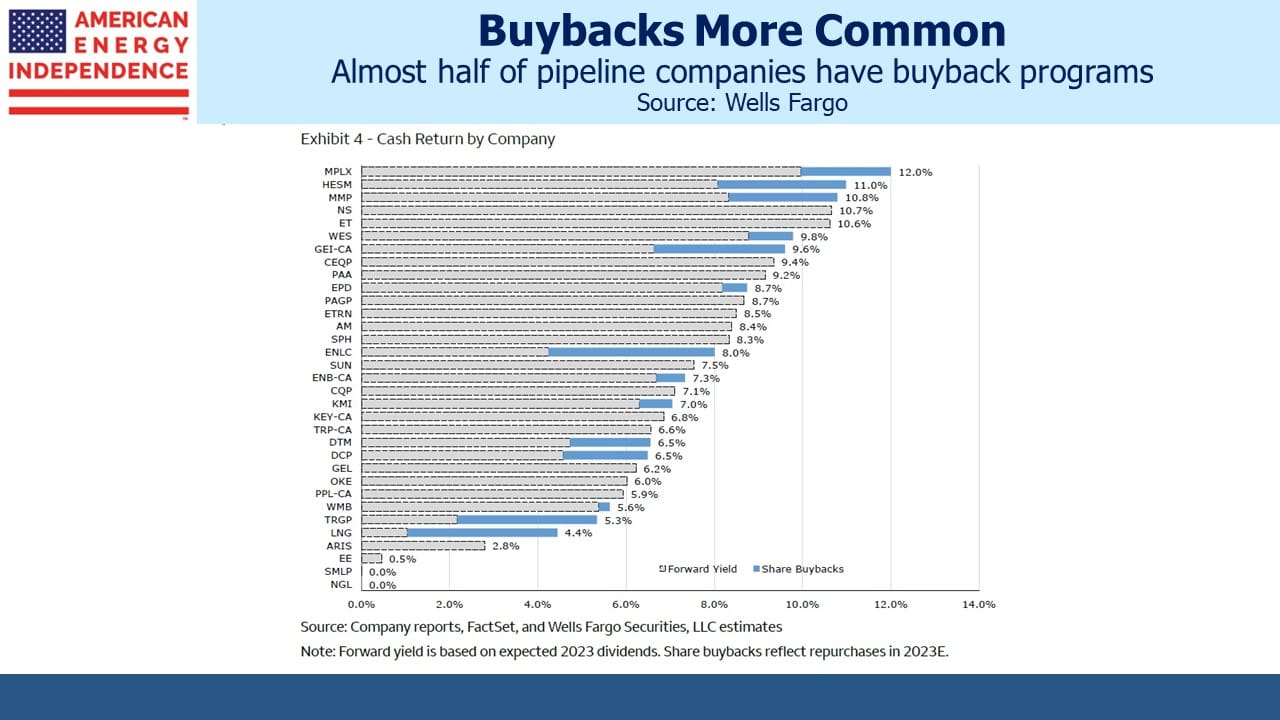

Encouragingly, KMI added $1BN to their buyback program. Given the stock’s poor performance for many years, this might be one of their best uses for excess capital.

We continue to own KMI but at a reduced size relative to its percentage of the sector’s market cap.

We have three funds that seek to profit from this environment:

Energy Mutual Fund Energy ETF Real Assets Fund