Can Pay Raises Keep Up With Inflation?

For the first time in history, nurses who work for Britain’s National Health Service went on strike last week. They’re demanding a 19% pay increase, to make up for current inflation as well as the “20 per cent that has been eroded” from pay over the past decade, according to union leader Pat Cullen.

Nurses in the UK occupy a special place in the public consciousness, evoking memories of Florence Nightingale who led a team of 38 to treat wounded soldiers during the Crimean War in 1854. Underpaid yet much loved is how many Britons feel towards them. In Germany, average pay for nurses is €33K ($35K). The US median is $78K. The average British nurse makes £26K ($32K). Some report relying on patients’ food at the end of the month while awaiting their paycheck.

Europeans are supportive of unions and tolerate strikes more than the US. Traveling by train from London to Paris last Friday, our daughter was advised to allow extra time to pass through Immigration, thanks to Brexit. The transit system faced another strike the following day, and her (perhaps over-protective) father reminded her not to get sick while the nurses were on strike.

The problem is that workers in many fields are getting pay raises less than inflation, imposing a drop in living standards. Congress shouldn’t have passed last year’s $1.9TN American Rescue Plan (ARP), and the Federal Reserve was at least a year late in shifting from its accommodative policy. These were two large mistakes. As a result, the Fed wants to drive unemployment higher, thereby pressuring real incomes. This is the consequence of the twin fiscal and monetary failures.

Pay that lags inflation requires workers to conclude no better alternative is available. There are signs of economic weakness. House prices are softening. November’s auto sales figure of 14.6 million (seasonally adjusted, annualized) is recession-like, with 15-17 million more typical when the economy is growing. Recession forecasts are common, but the jobs market remains strong.

In April 2021, CPI registered 4.2% year-on-year, just when Congress passed the ARP and checks started going out to tens of millions of Americans. We’re close to two years of above target inflation. It’ll increasingly figure in wage negotiations until there’s more slack in the labor market.

The Employment Cost Index (ECI) is rising at 5%, but adjusted for inflation is –2.9%. Year-end pay reviews are the norm across corporate America. For the vast majority of people who have held their current job for at least the last year, first quarter pay raises are common.

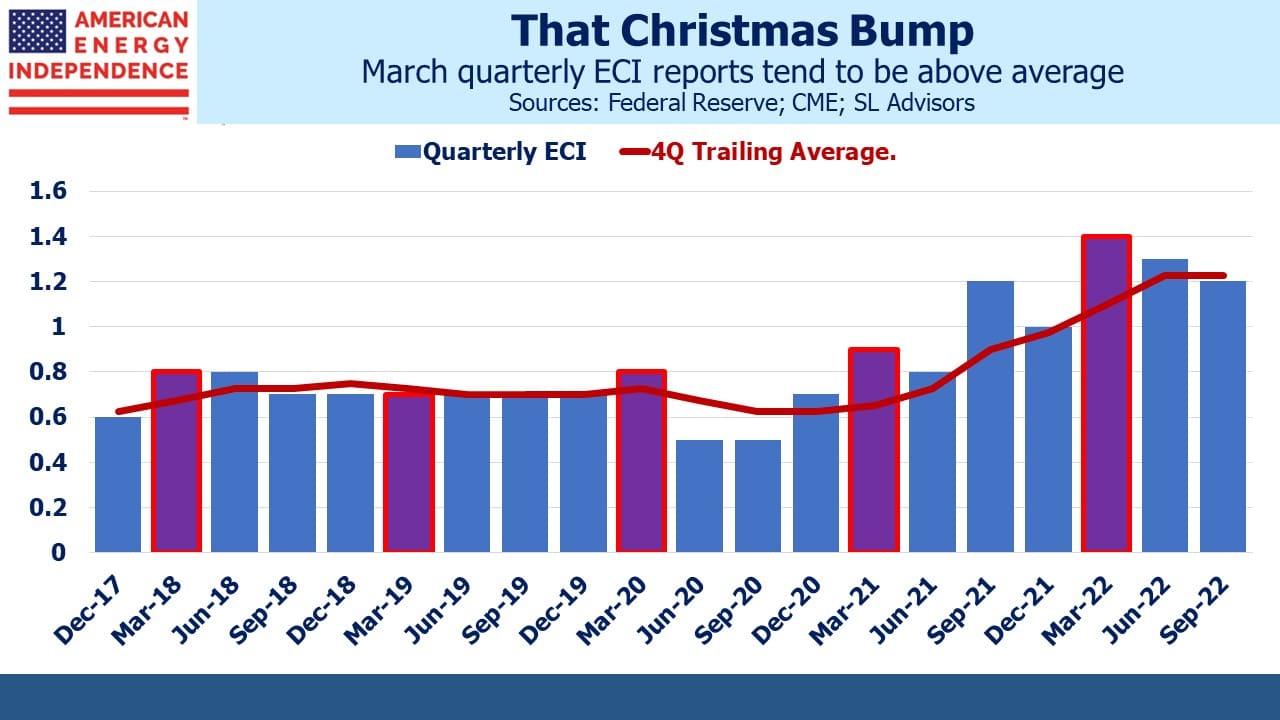

The ECI is seasonally adjusted, but the adjustment factors may be inadequate this time because annual raises will likely be bigger than usual. There are signs this is already happening. For several years the March ECI report has been above the trailing 4Q average. This bias has become more noticeable in the last two years. The seasonals haven’t caught up with higher annual pay raises to reflect increased inflation.

This suggests that wage inflation reported in the March ECI will be above trend and higher than the Fed would like. It’ll be published in April so is some way off – we’ll revisit this topic closer to the date. Some annual pay raises occur during the 4Q so will be picked up in January’s release, but so far there hasn’t been any visible anomaly in past releases of the December ECI.

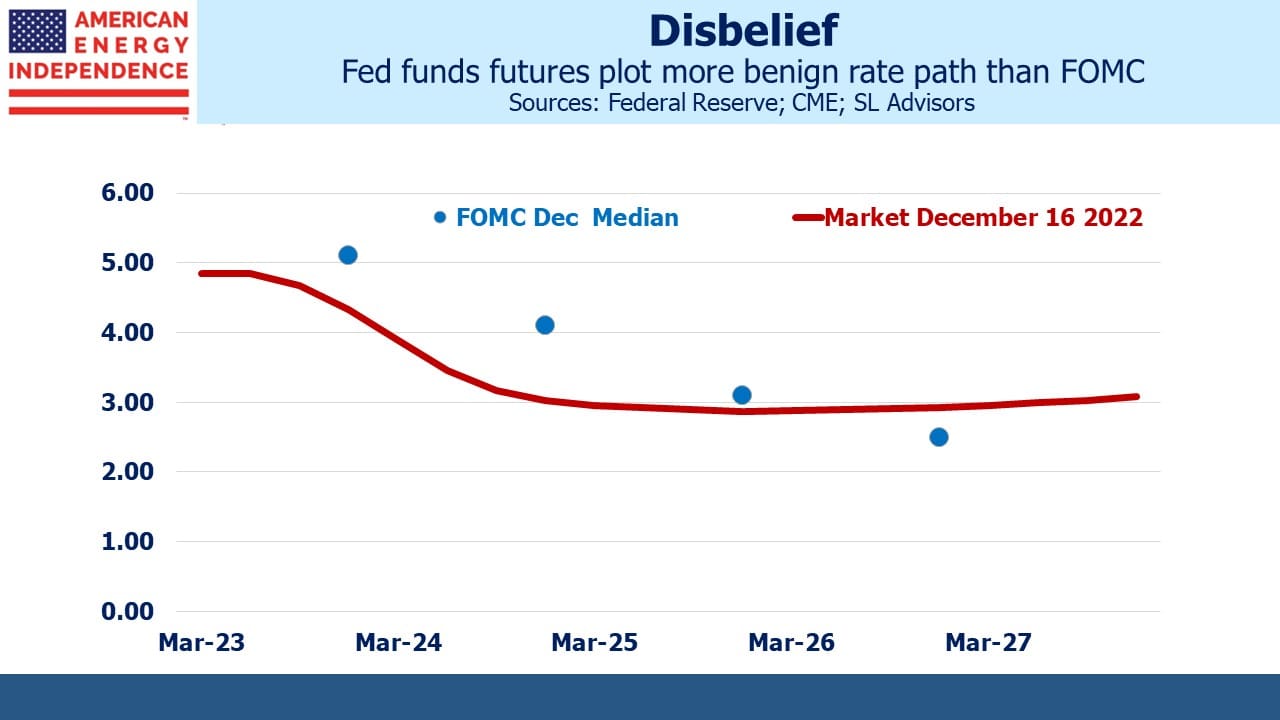

Last week the FOMC updated their Summary of Economic Projections (SEP). A more hawkish path for the Federal funds rate depressed stocks. The biggest discrepancy is with Dec ‘24 futures which yield 3%, 1% less than the SEP. The market thinks a recession is more likely than the Fed does, and therefore expects the Fed to cut rates next summer.

Inflation expectations remain well contained, which provides an exit ramp from tight policy anytime the FOMC wants to use it. But Fed chair Jay Powell doesn’t sound as if 4.6% unemployment (the SEP forecast for the end of next year) will be problematic. Economists debate what unemployment rate represents full employment. Its snappy title is the Non-Accelerating Inflation Rate of Unemployment (NAIRU). You only know where NAIRU is when falling unemployment causes inflation. Today’s 3.7% rate is well below it.

The St Louis Fed has a chart showing NAIRU at 4.4%. Some economists think it’s higher because of Covid-induced goods-inflation and reduced labor force participation. The Fed is unlikely to reduce rates until they’re sure the unemployment rate is above NAIRU, because they’ll be motivated to avoid yet another policy error. Once they start cutting rates, if inflation doesn’t keep falling, they’ll face no shortage of critics.

Jay Powell insists they’ll stay the course and maintain restrictive policy until inflation is clearly returning to 2%. When the blue dots on the SEP differ from the futures market, it’s usually resolved at the cost of the FOMC’s forecasting reputation. This time may be different.

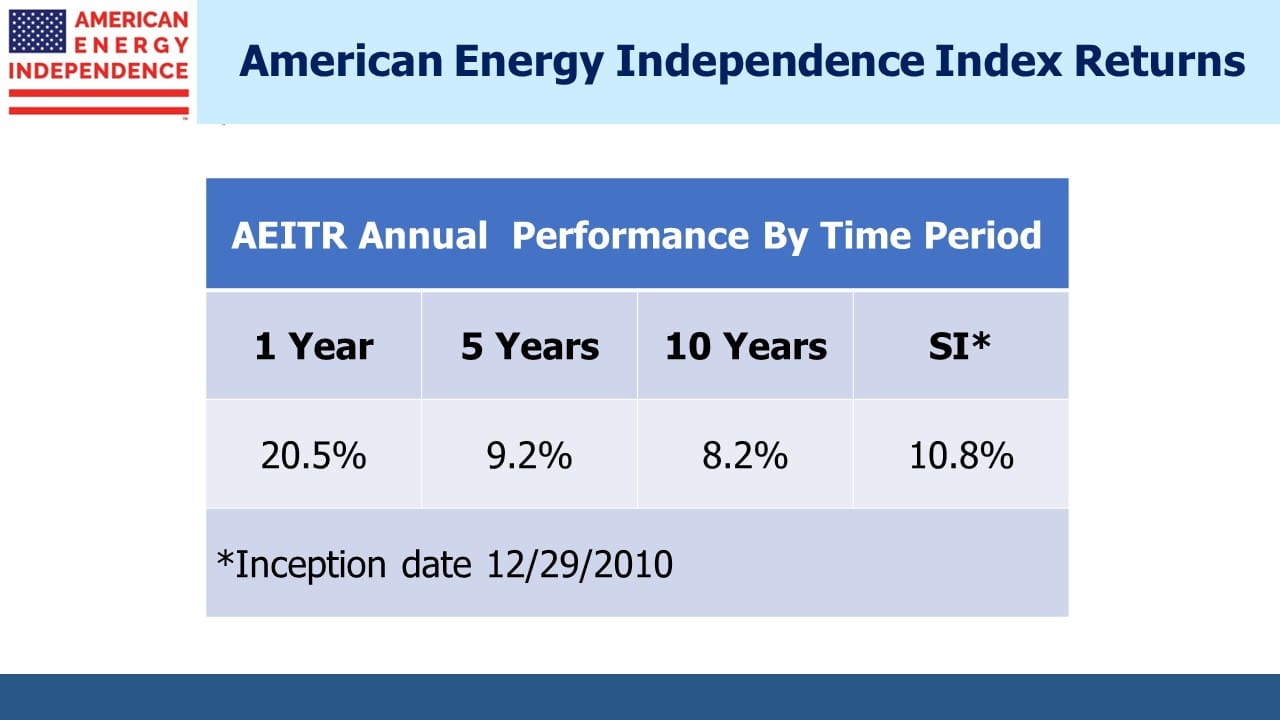

We have three funds that seek to profit from this environment:

Energy Mutual Fund Energy ETF Real Assets Fund