The Super Cycle Or Peak Oil?

In March of 2020 when crude oil was collapsing dragging energy stocks, including pipelines, along, I tried to focus on the positive, which was that it had become cheaper to drive places. Except there was nowhere to go because of the lockdown. And even if there had been, I would have had to make roughly three round trips to the moon and back to generate enough savings on gasoline to compensate for my losses on infrastructure.

What some might deem an imprudently high allocation to the sector was paired with a timid appetite for leverage (ie there was none). With no need to sell I was miserable only until prices started recovering. Having endured low oil prices, I find high prices wholly more agreeable.

Therefore, JPMorgan’s chart depicting a widening supply deficit over the next several years causes me little angst. Those around me might even enjoy my pleasant demeanor if the forecast is true.

Interestingly, JPMorgan’s 2028 forecast of global demand matches the International Energy Agency (IEA) in their Oil 2023 publication at 105.7 Million Barrels per Day (MMB/D), an annual growth rate of just under 1%. Both agree that gasoline demand will soften while other oil products such as jetfuel, LPG and heating oil will continue to rise.

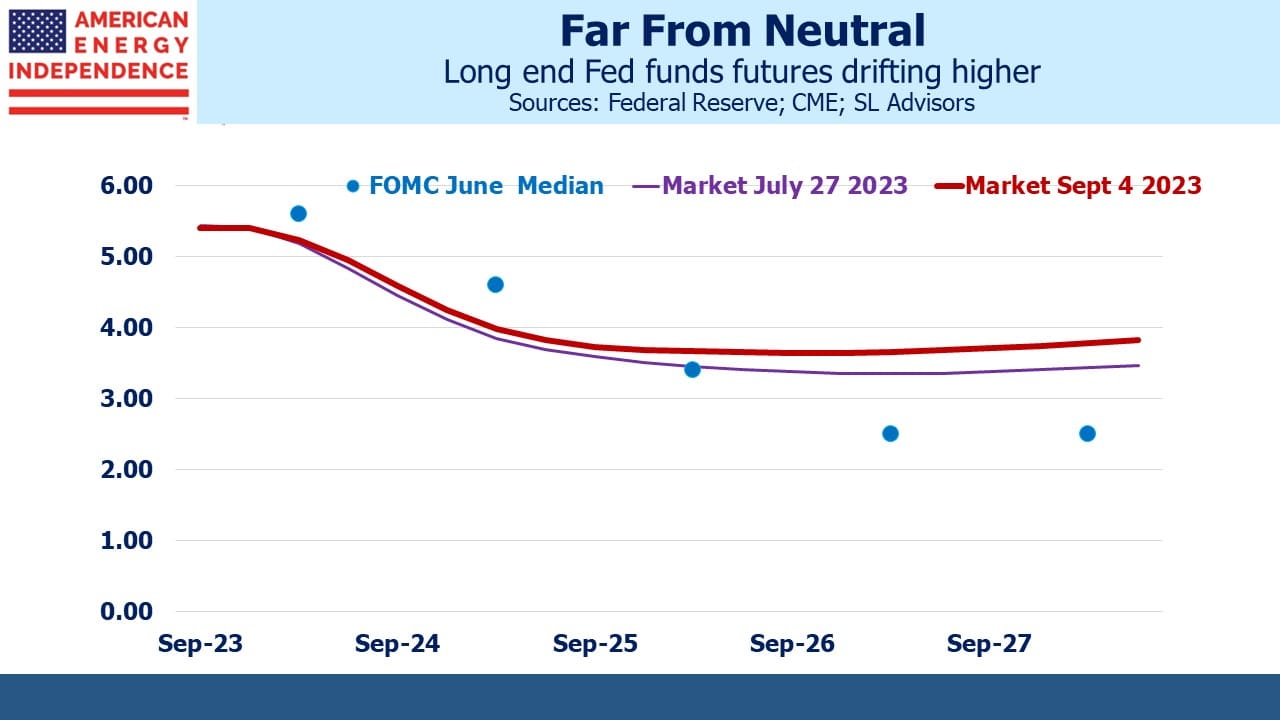

However, they reach very different conclusions on supply. The IEA is more bullish on US output, and therefore doesn’t foresee a supply/demand imbalance. By contrast, JPMorgan expects only 1% annual US production growth. They attribute this to (1) declining productivity, (2) continued focus on accretive projects to drive shareholder returns, and (3) higher interest rates. They see US upstream capex declining 7% annually through 2030.

The result is that JPMorgan is overweight global energy, proclaiming the “Supercycle returns.” They believe, “the upside risk to oil is $150 per barrel over the near to medium term.” They see a “higher for longer” outlook as financial discipline and increased cost of capital combine with “institutional and policy led pressures driving an accelerated transition away from hydrocarbons and peak demand fears.”

The IEA report strikes a more politically correct tone, asserting that increased investment in renewables is bringing “peak oil demand into view.” Reading it is supposed to leave investors in traditional energy despondent. JPMorgan disagrees: “We don’t see peak oil demand on our investment horizon (2030)”. They have a multi-year bullish outlook.

The IEA has a more optimistic supply view combined with a more pessimistic demand outlook. Energy producers embracing both would be disinclined to invest in the very supply growth the IEA expects. They’re forecasting peak oil within a decade or so to stimulate increased capex in oil projects that typically require well over a decade to generate an acceptable return. Only one part of that scenario can plausibly occur.

Analysts at Citi and Bank of America are similarly bullish, which contrarians will view as evidence of an already crowded trade.

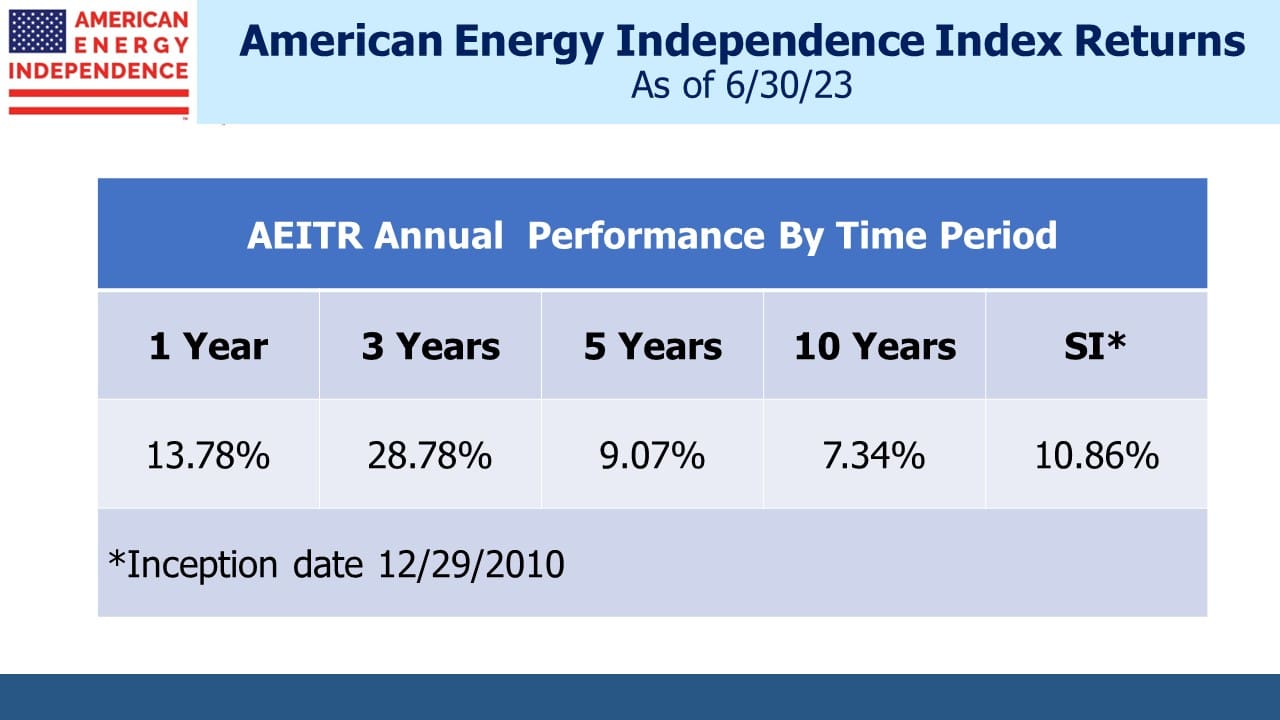

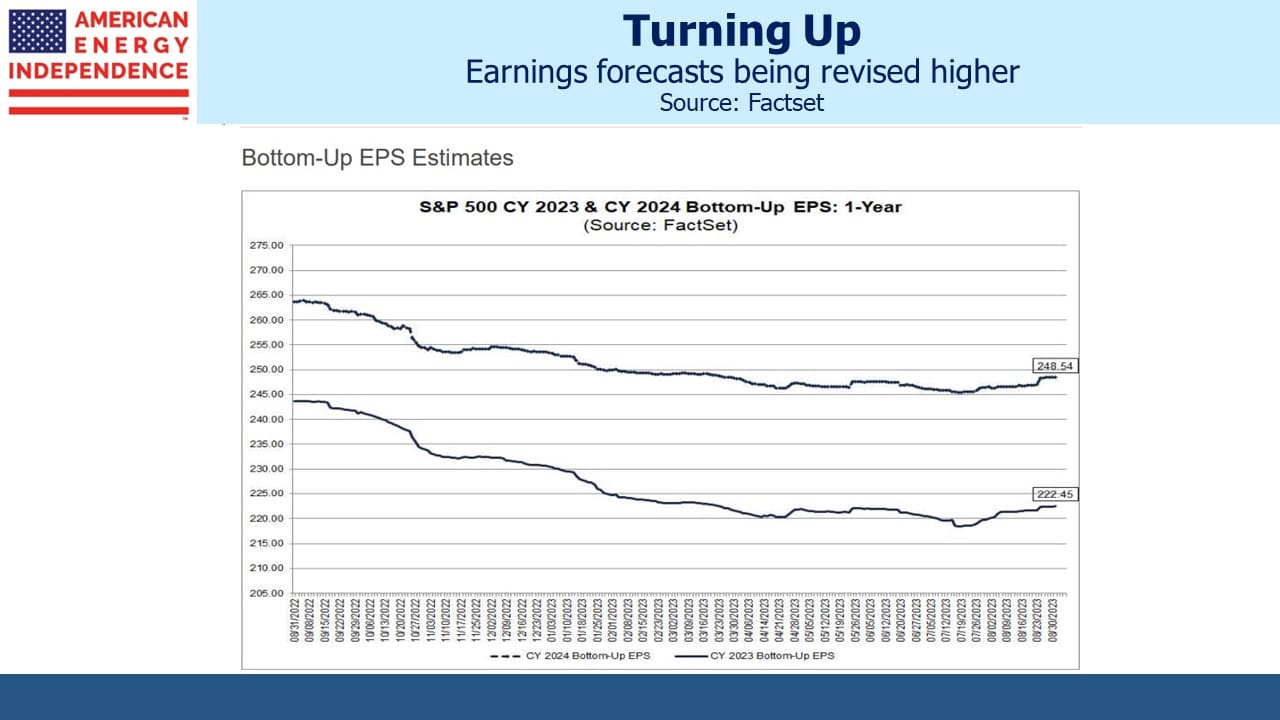

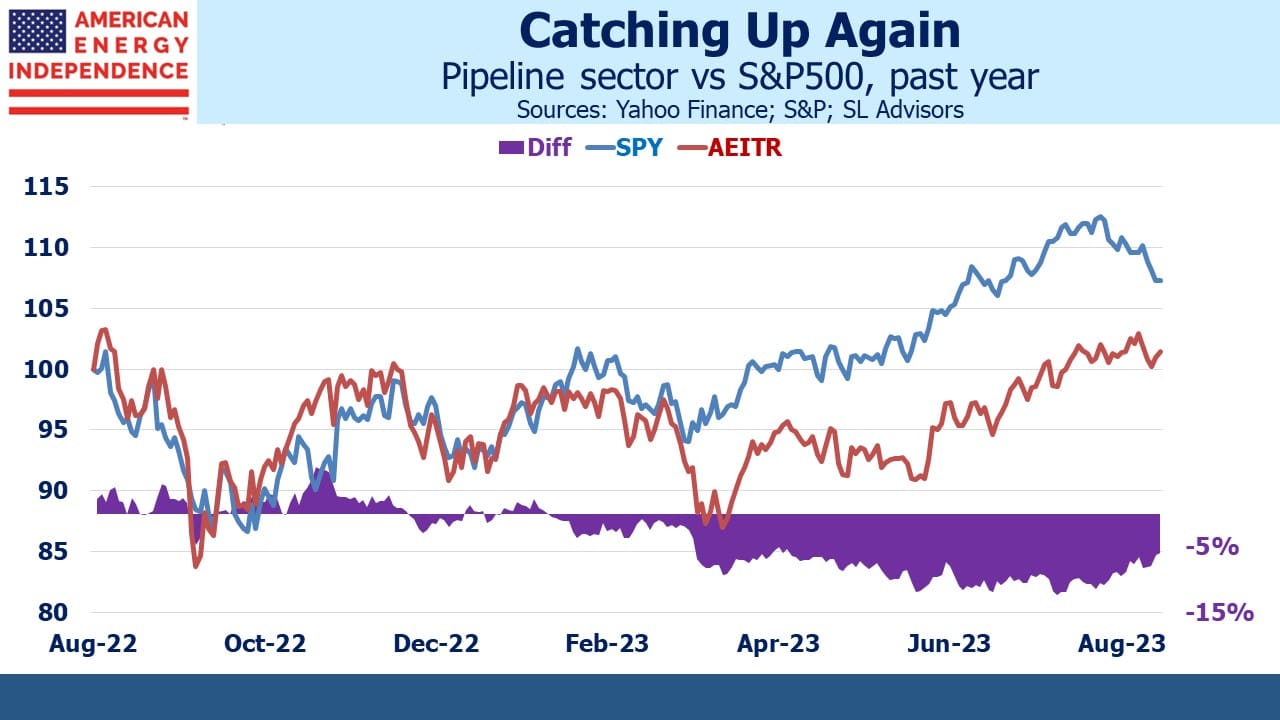

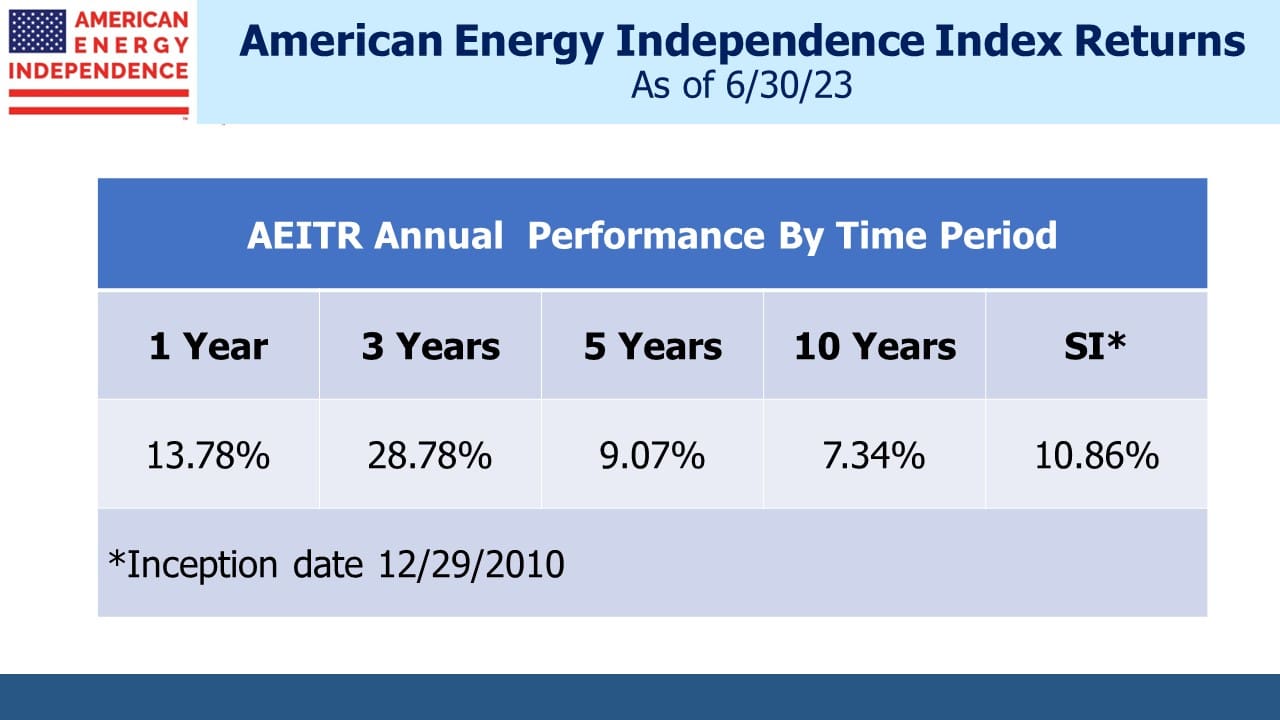

If crude oil was falling, we’d note the unimportance of commodity prices to the pipeline sector. Rising prices reflect improving sentiment towards the energy complex and perhaps a modest EBITDA uplift for midstream infrastructure. But given attractive valuations, as generalist investors have begun to revisit their exposure to energy it doesn’t take much to push the sector higher. Market outperformance of the American Energy Independence Index has coincided with the rally in crude oil. They’re likely to continue moving up together.

Oneok’s (OKE) acquisition of Magellan Midstream (MMP) was approved by owners of both companies last week. Now comes the big rebalancing. MMP unitholders will receive $25 per unit, which means about $5BN in cash will be available for reinvestment early this week. Some will be set aside for taxes, but much of what’s left will go back into midstream c-corps, which should give the sector a bid.

$5.6BN is the amount of MLPs the Alerian MLP ETF (AMLP) would have to sell if they decide to rebalance away from the declining MLP sector towards c-corps. Wells Fargo reviewed the challenges this is creating for MLP-dedicated funds that follow Alerian indices. It’s an issue we have noted in the past.

The family of Invesco Steelpath funds would have to sell around $4.5BN in MLPs if they similarly rebalanced. Neither will want to make such a choice after the other. And if Alerian changes their index construction it might force the issue.

As much as $10BN of MLP positions might be swapped into c-corps if such a rebalancing goes ahead. Wells Fargo reviewed the available options but stopped short of predicting what will happen. The issue won’t go away. Fund flows ought to favor c-corps over MLPs.

We three have funds that seek to profit from this environment:

Energy Mutual Fund Energy ETF Real Assets Fund