Hedging with Energy

It’s always interesting to learn how financial advisers use our energy infrastructure investments in their portfolios. Often, it’s for income, because the 6-7% yields are well covered by cash flow, growing and supported by continued reluctance to boost growth capex. America has the pipeline network we need. New construction gets held up by court challenges from climate protesters, with the delays increasing costs. Equitrans with their Mountain Valley Pipeline project is an example. They announced a further delay because hiring is hard. Their recent 8K SEC filing noted, “multiple crews electing not to work on the project based on the history of court-related construction stops when there’s the risk of another court order stopping work.”

Canada’s federal government probably owns the record for cost over-runs, with a 4X increase since they acquired the TransMountain expansion from Kinder Morgan five years ago (see Governments And Their Energy Policies). Developments like these are dissuading growth projects, which is why pipeline sector dividends are growing. A dollar not spent on capex is a dollar coming back to shareholders, through a dividend hike or stock buyback. It’s hard not to love climate extremists.

Because of the prospect of rising payouts and buybacks, we think pipelines offer income with growth. Who says you can’t have both?

Some financial advisors like energy because it’s relatively uncorrelated with other sectors. We think this makes a lot of sense (watch Will Geopolitical Risk Effect the Energy Market?).

I was with one such investor last week who uses midstream energy as a hedge against more conventional equity exposure. He’s very happy with the results, and his business is growing strongly because of this and doubtless many other good calls for his clients.

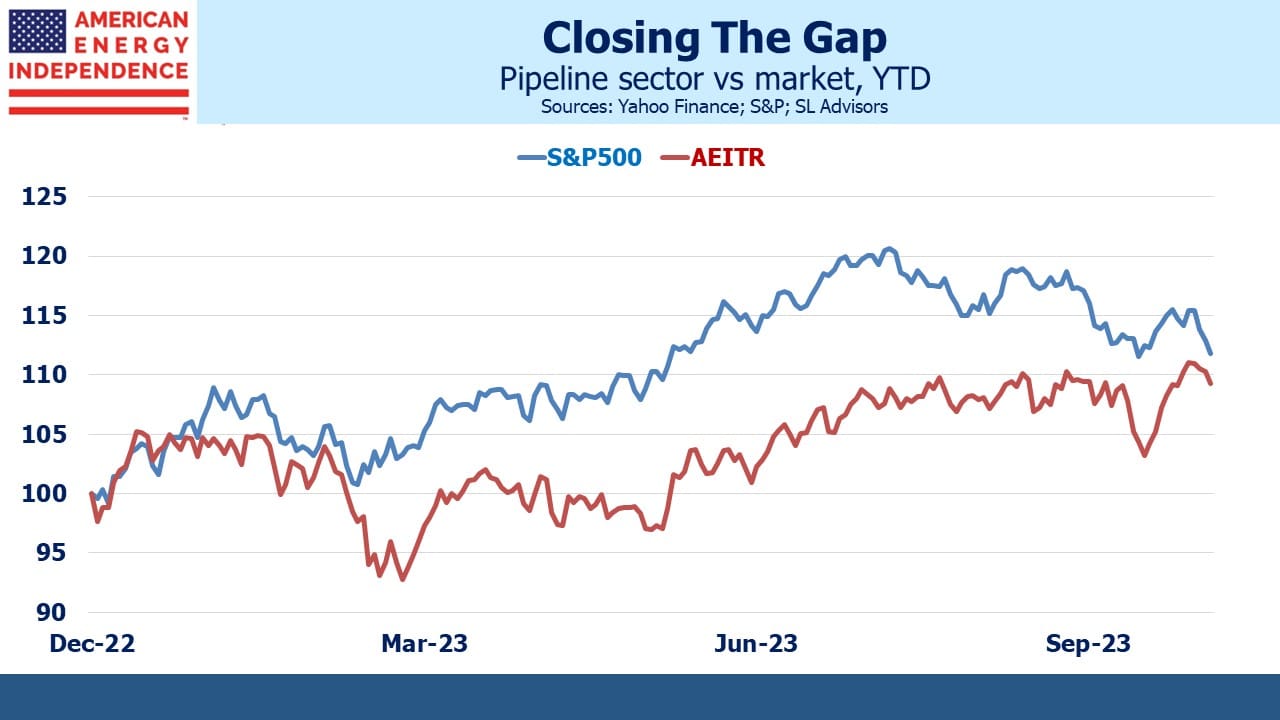

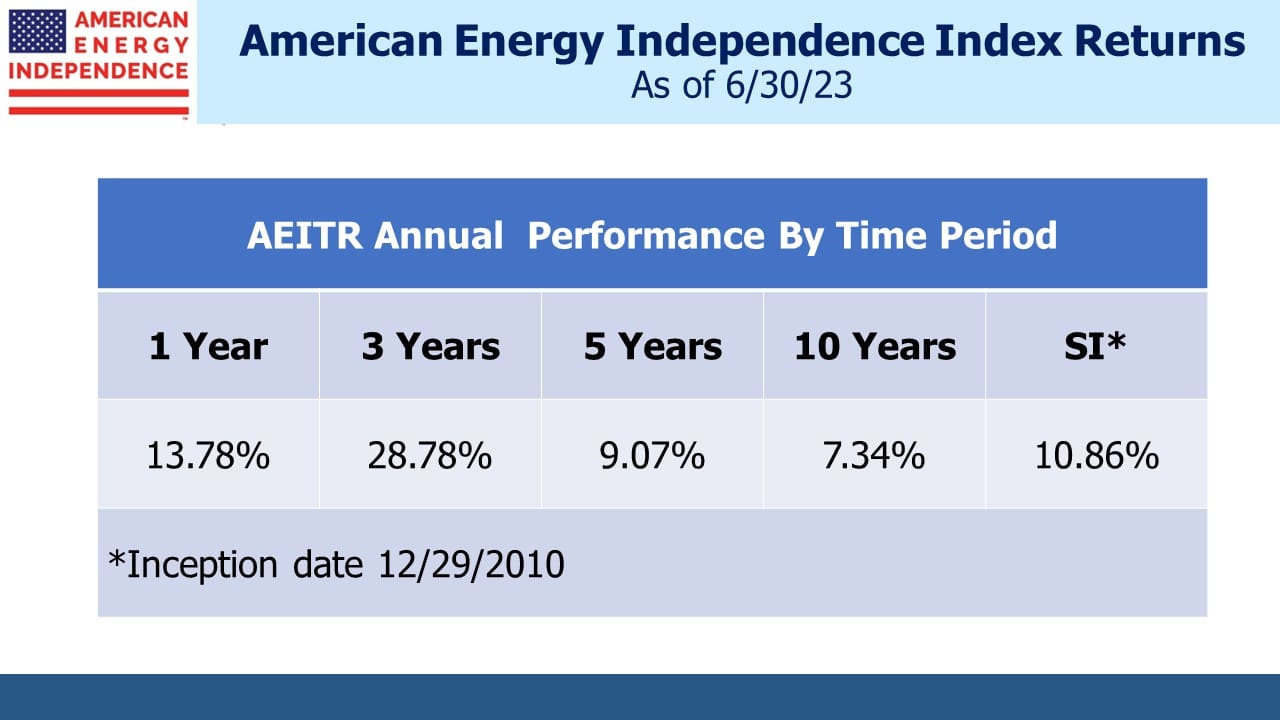

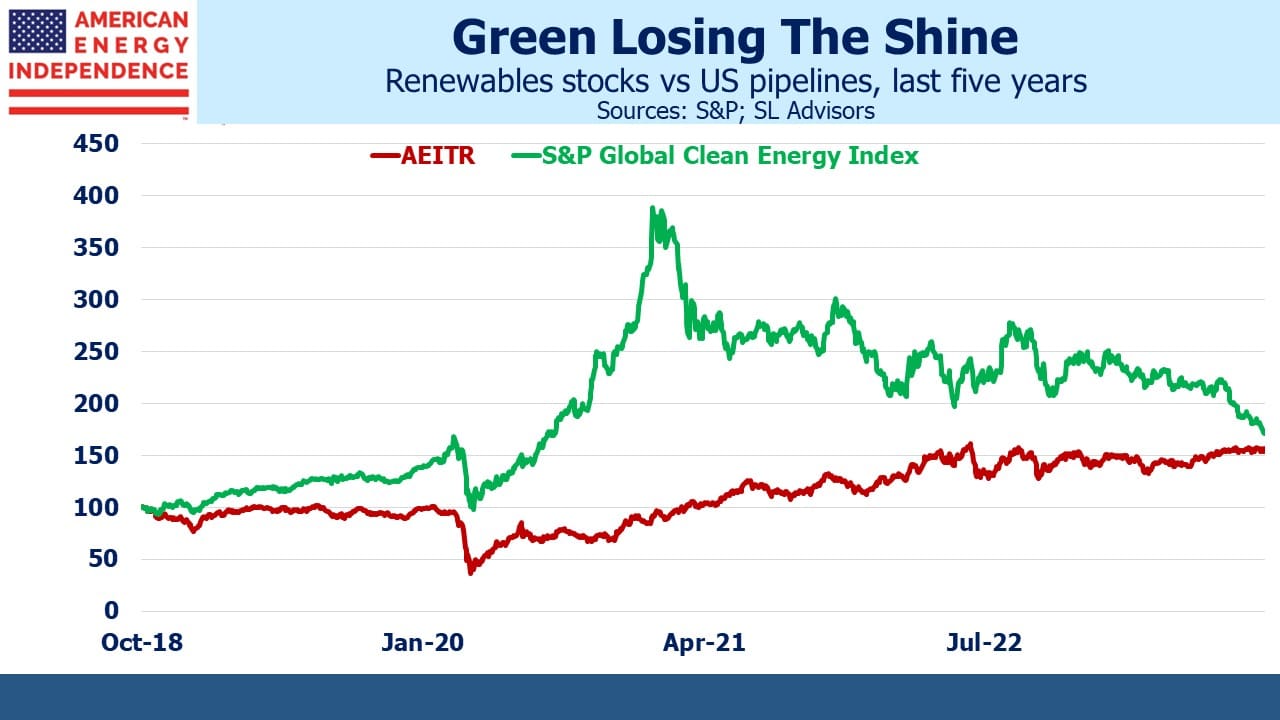

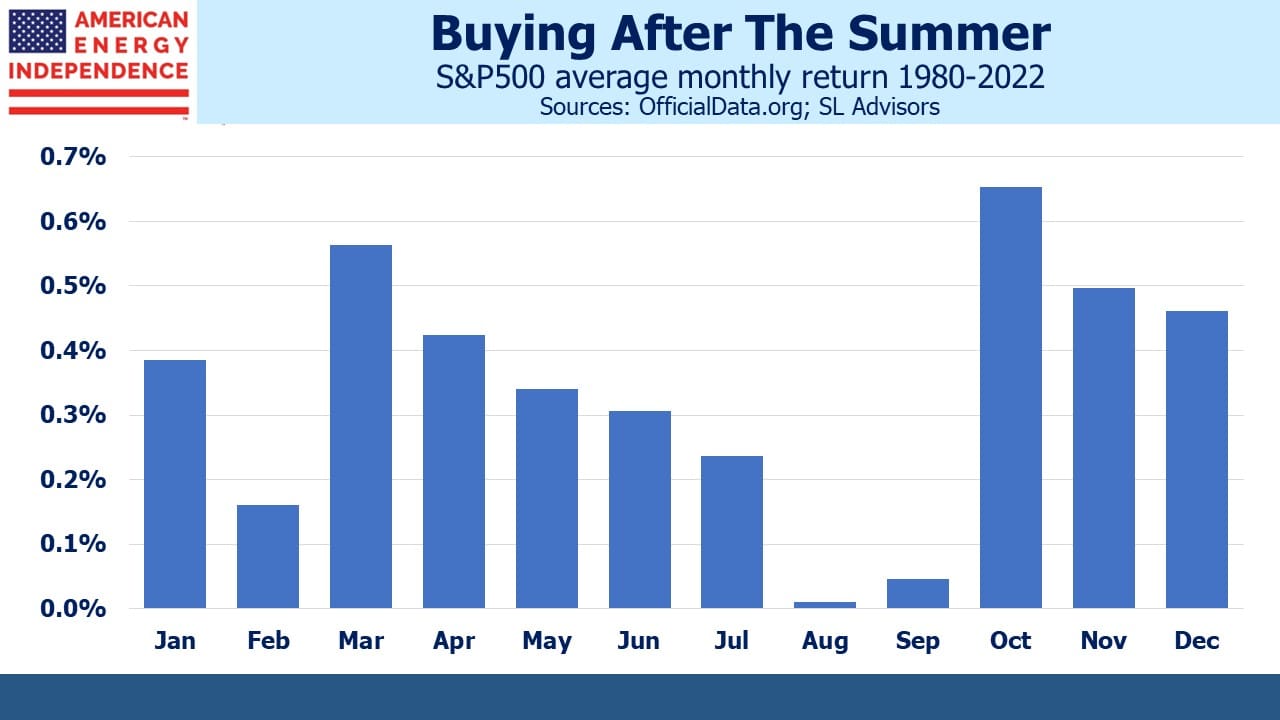

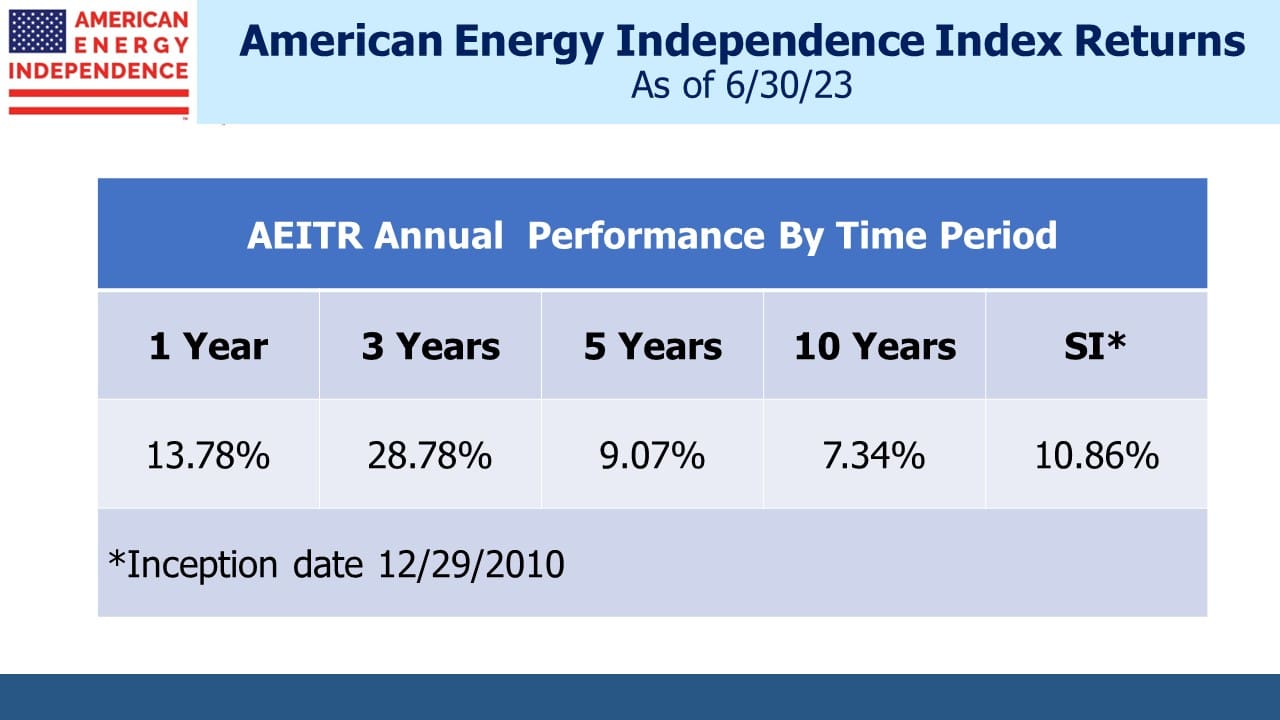

The American Energy Independence Index (AEITR) handily beat the S&P500 for the past two years. Pipeline companies are not popularly linked with AI so have lagged the market this year. However, the gap has begun to close as Israel has responded to the shocking terrorist attack by Hamas, ratcheting up tensions across the region.

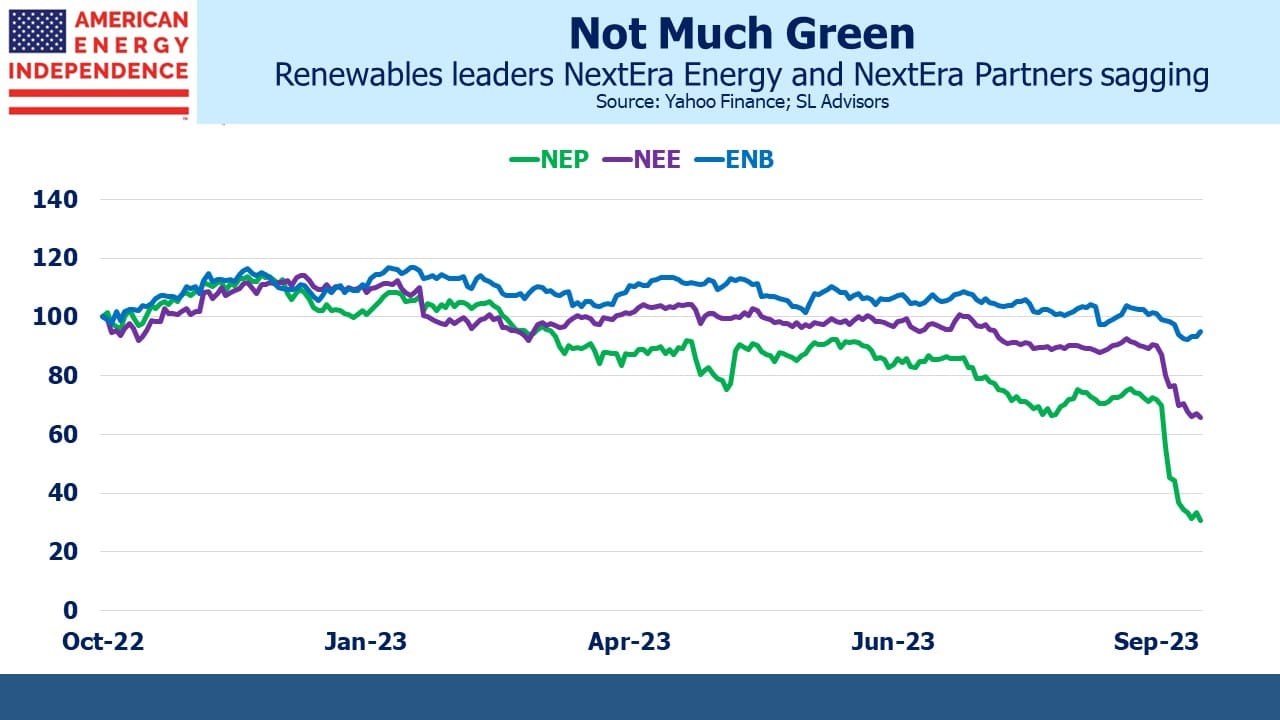

By mid-July the S&P500 was 13% ahead of the AEITR. As of Friday the gap had shrunk to 2.6%. Dividends help – the S&P500’s dividend yield is a paltry 1.6%, less than a quarter of what pipelines pay. Enbridge (ENB) yields over 8.1%. Its C$3.55 dividend has grown annually for 28 years, a record management has pledged to continue. It represents an extreme case of the contrast between energy infrastructure and the overall market. ENB still looks like a good pairs trade with a short S&P500 position. Notwithstanding your blogger’s substantial overweight to the sector, I recently put that trade on too.

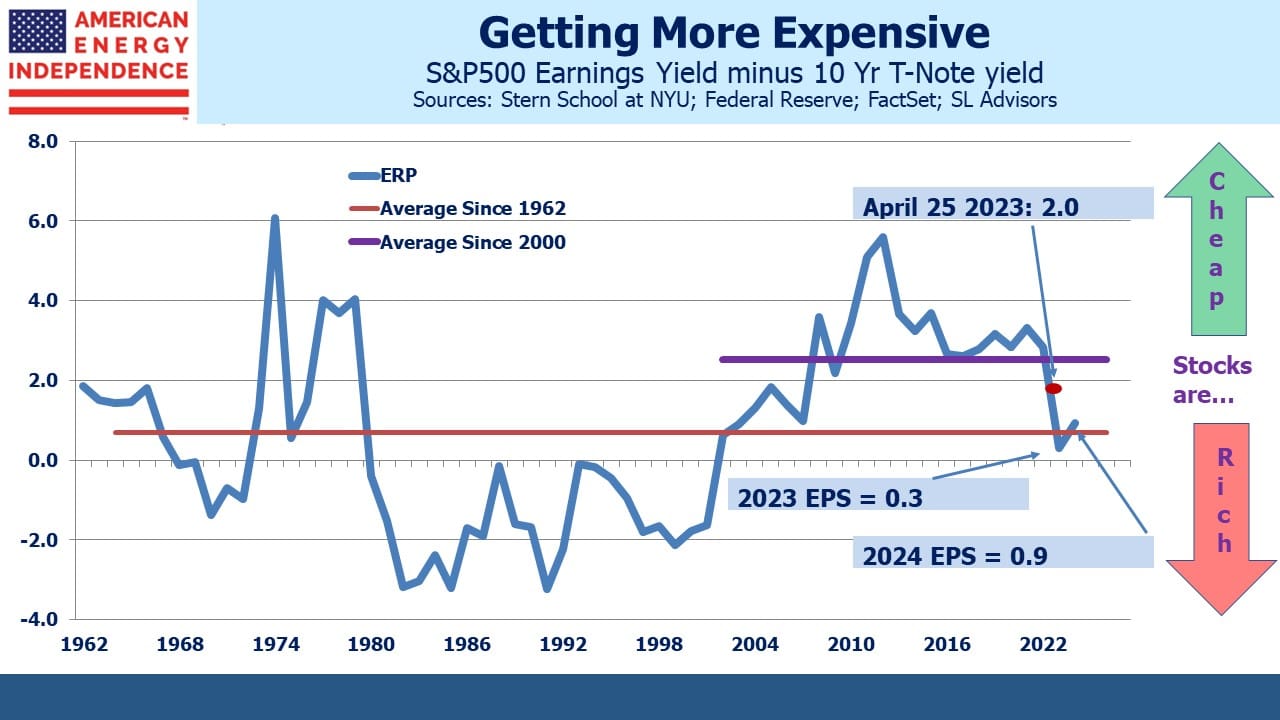

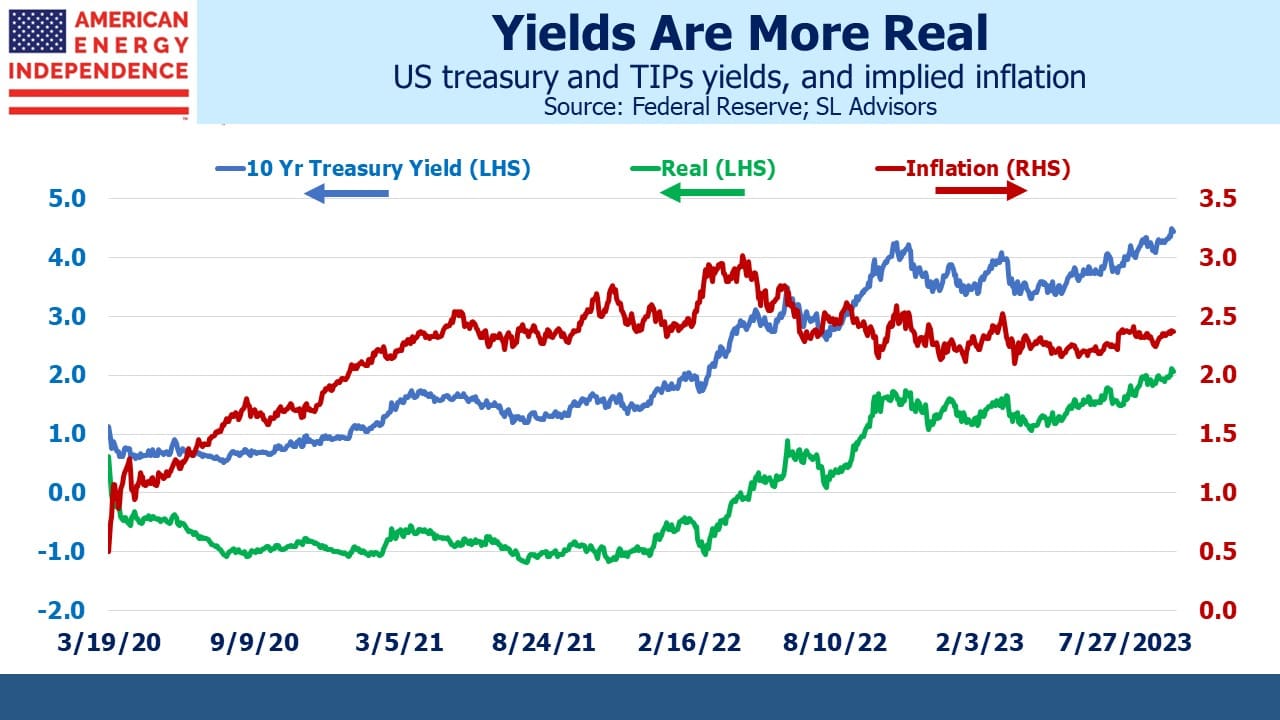

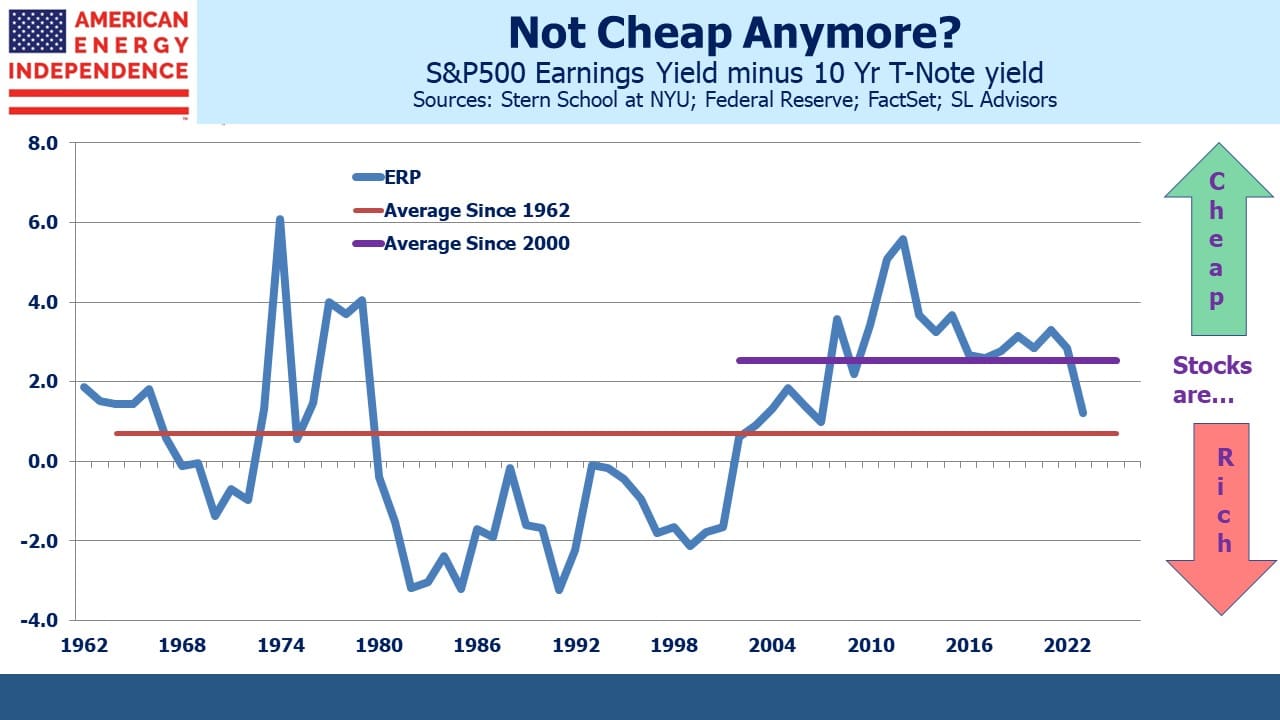

Stocks had a bad week. But they still don’t look that cheap. Six months ago (see Inflation vs Regional Bank Crisis) valuations were just average compared with the past couple of decades. Since then, the S&P500 has risen 4%, 2023 forecast earnings are flat and declining, and the ten year note has risen 1.5%.

Today’s Equity Risk Premium (ERP) of 0.3 is the lowest in two decades. Even using 2024E EPS, at 0.9 it’s still unattractive. Moreover, earnings forecasts have been declining in recent weeks, with few upward revisions likely other than for the defense sector.

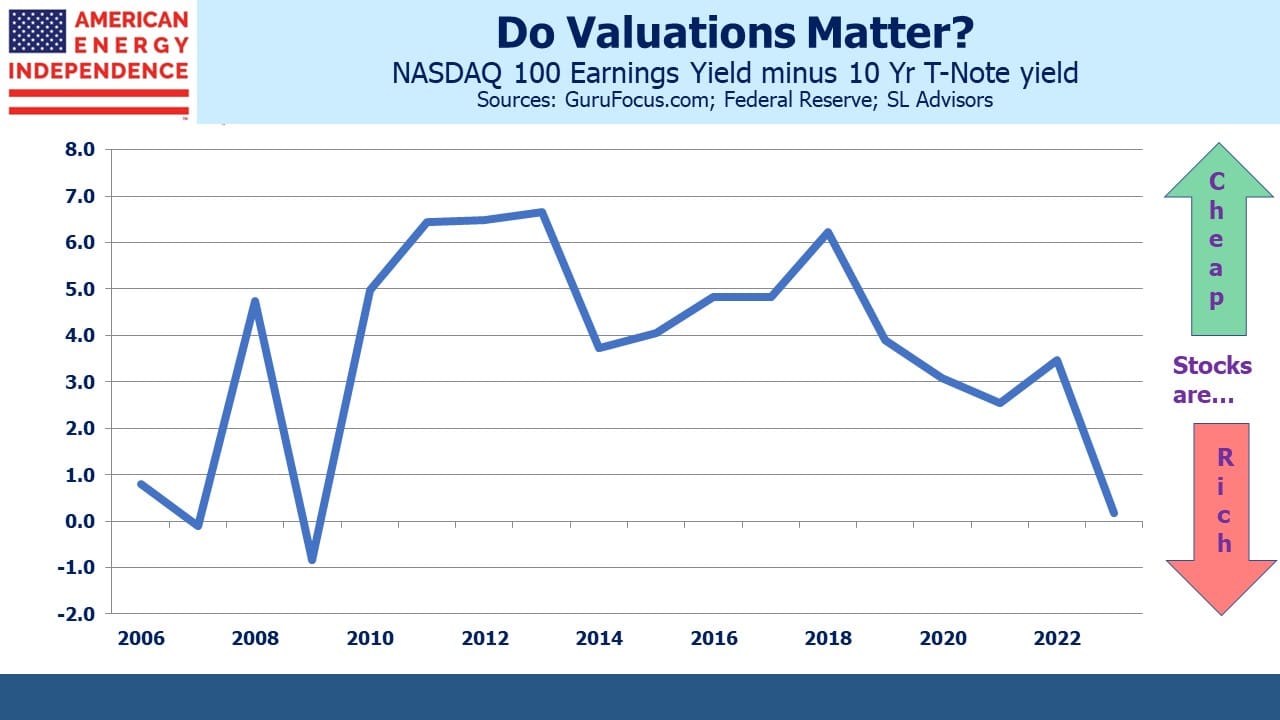

We’ve also included the ERP for the NASDAQ 100. This is an unconventional way to evaluate the tech sector, and your blogger long ago concluded that he felt more comfortable with value stocks. Over the years I have carefully avoided expensive investments with high growth rates, and such omissions have not always been to my advantage.

Nonetheless, it’s hard to resist publishing the Tech sector ERP chart. Rising bond yields are doubly bad here, because as well as offering a relatively stable return they mean a higher discount rate/lower NPV on those far bigger, far away profits.

Tech stocks lost three quarters of their value during the dot.com collapse. Even during the 2008 great financial crisis they were down by half. Today’s ERP for the sector is around the same level.

This blog doesn’t promise to get you into tech stocks at the low. But they don’t look cheap.

Electric vehicle (EV) sales are flattening out. Everyone I know who owns a Tesla loves it, but also has another car for long drives. But my circle of friends is not representative of America. A journalist on the NYTimes Climate desk recently reported on an EV trip he made in South Dakota that ended with his Volvo C40 being towed because it ran out of juice.

We still worry about our phone batteries going dead.

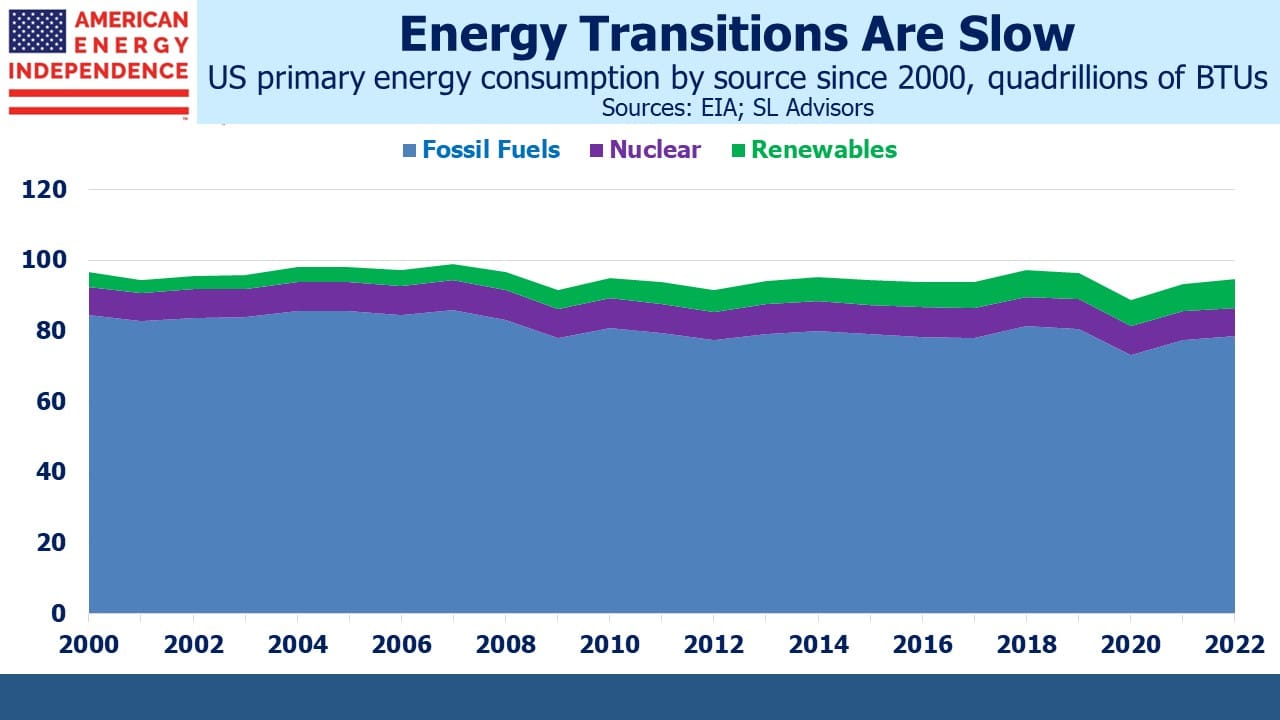

EVs seem like fun, but compared with much of the world, in the US we (1) drive farther, (2) drive bigger cars, and (3) enjoy relatively cheap gasoline. EV penetration looks as if it’ll be slower than many fans expect.

We have three have funds that seek to profit from this environment:

Energy Mutual Fund Energy ETF Real Assets Fund