The 21st Century Fuel: Natural Gas

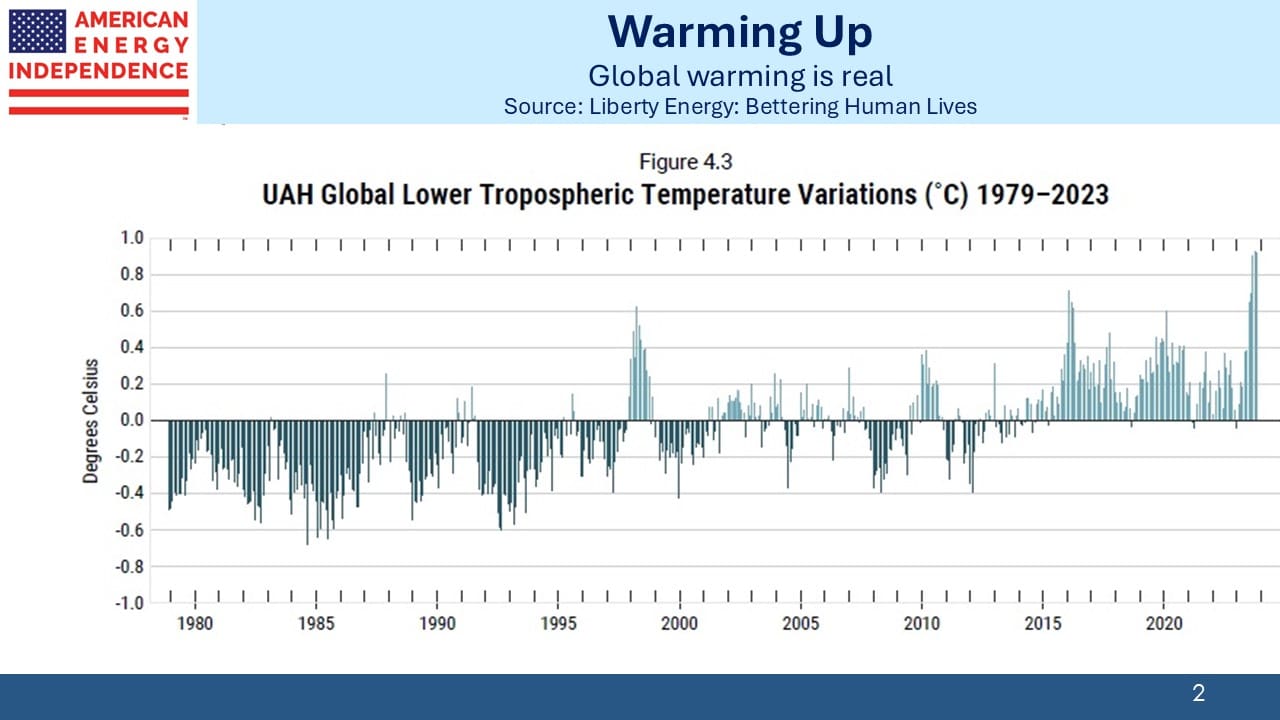

In recent years as extreme views on climate have become increasingly fringe, no hydrocarbon has enjoyed more of a reassessment than natural gas. Enbridge CEO Greg Ebel talks about the “energy evolution” rather than a transition.

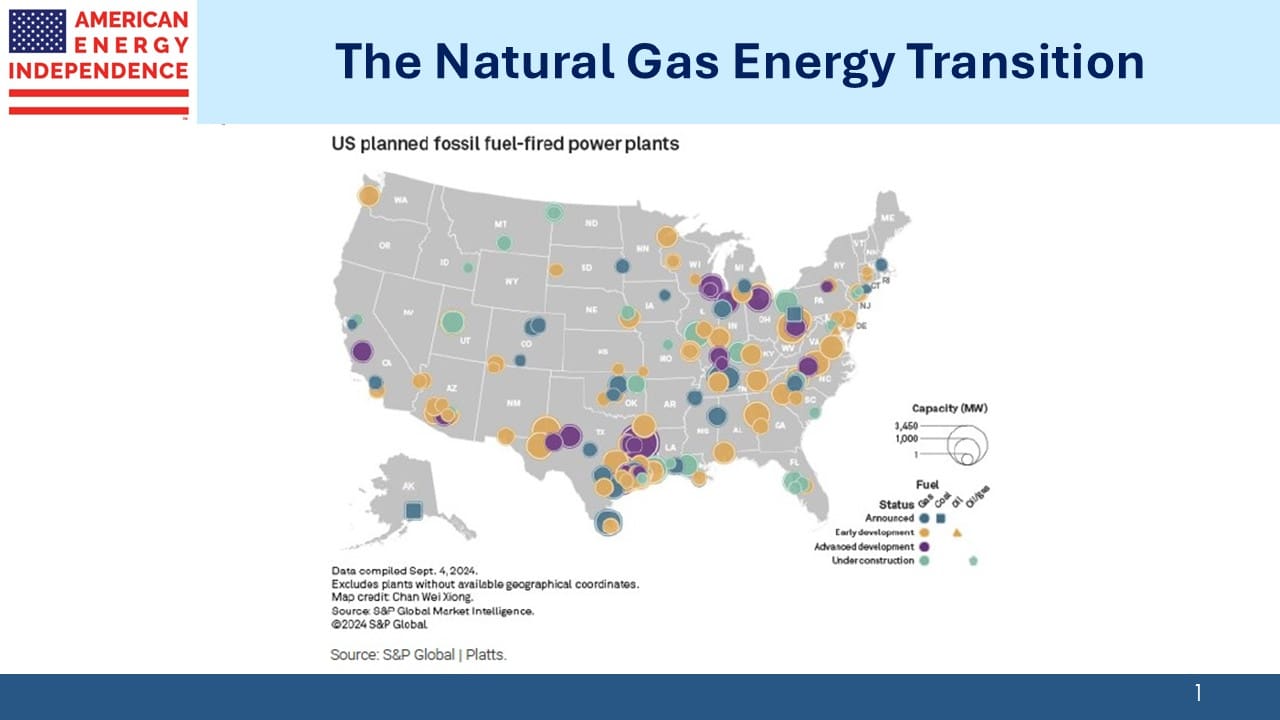

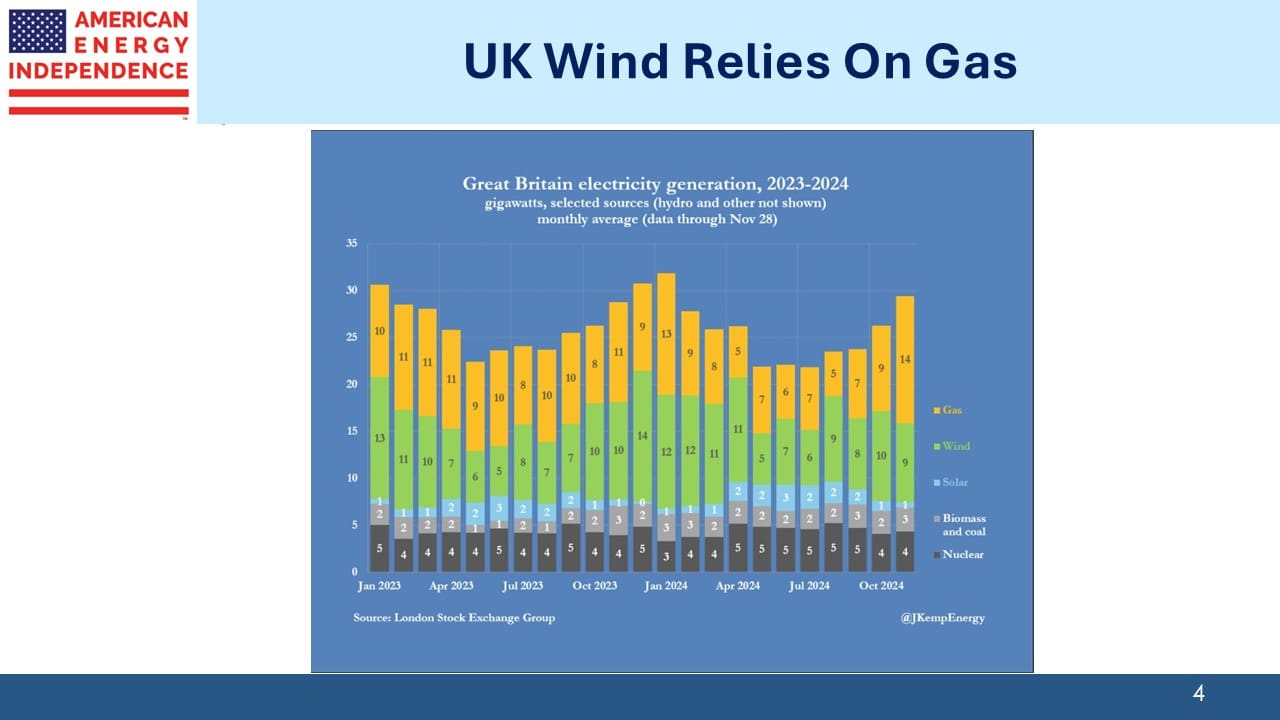

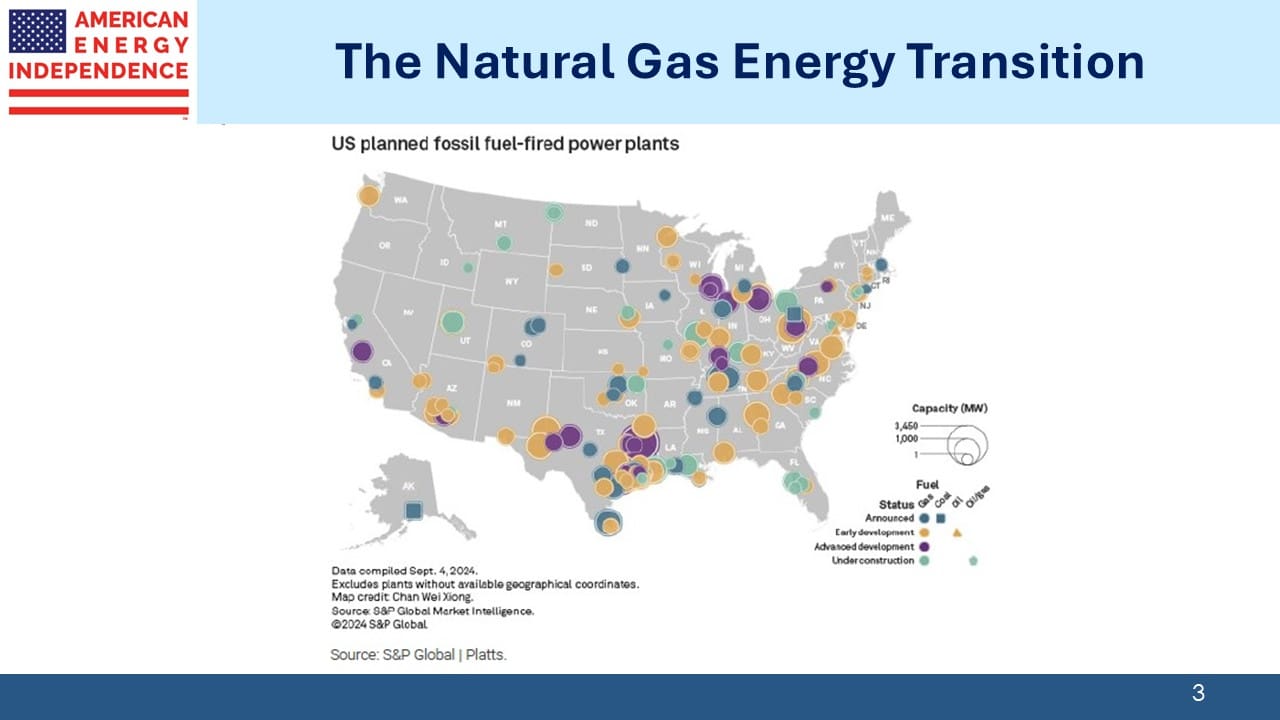

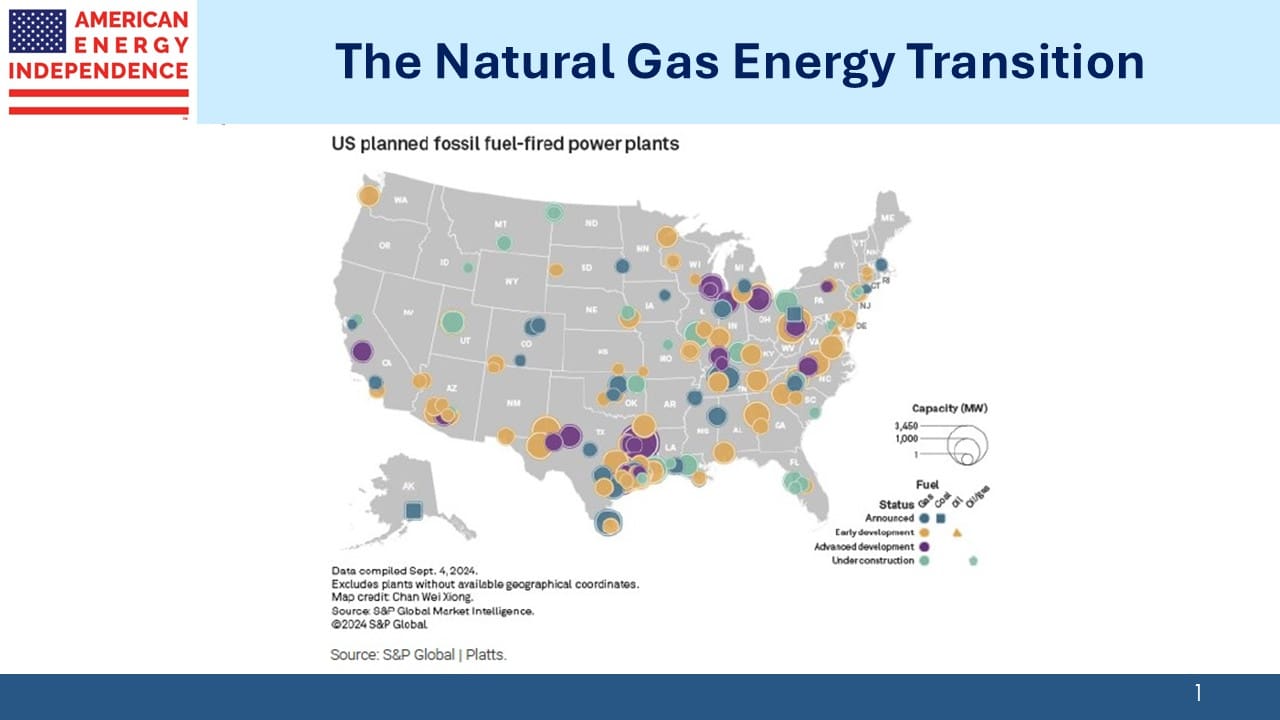

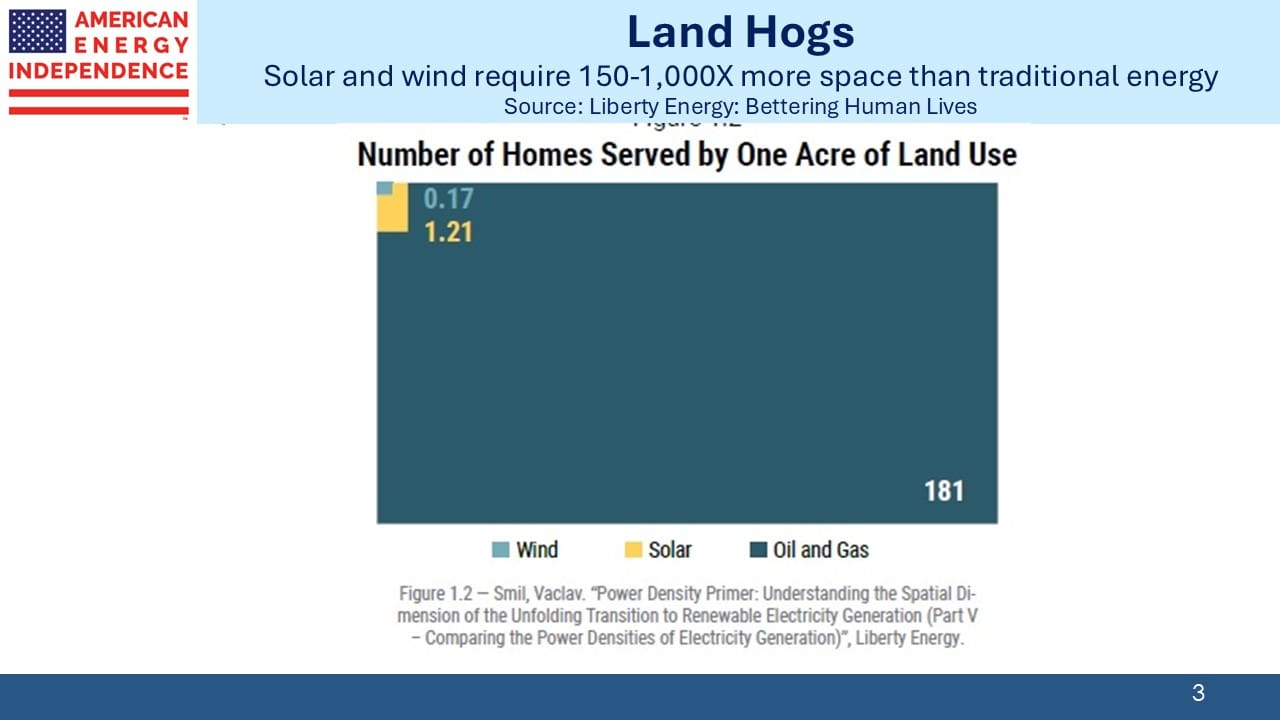

The US is adding over 140 new gas power plants this year as demand from data centers builds. Accommodating the intermittency of solar and wind is often achieved with supporting gas peaker plants, which have the ability to ramp up when it’s not sunny or windy.

There are even efforts to produce Renewable Natural Gas (RNG), which simply means it’s natural gas produced synthetically with low emissions rather than extracted from underground.

Divert is a company based in Massachusetts that takes food waste and by letting it decay in an anaerobic environment (ie deprived of oxygen), derives methane (natural gas). In a podcast (listen to Energized; The Future of Energy) CEO Ryan Begin explains how the process works. Enbridge is an equity investor and last year signed a $1BN infrastructure agreement with Divert to help them develop their business. Enbridge also sponsors the podcast.

CEO Begin goes on to explain how food waste is mostly water, so the vast tanks they build are in effect water treatment plants. Their inputs come from food processing companies, when they have to dump a batch of product that was contaminated or otherwise improperly produced. Supermarkets are another important source.

Most discarded food winds up in landfills where the methane it generates while decaying goes into the atmosphere. Because methane is a greenhouse gas, Divert can show that its business is helping the climate as well as making something useful out of waste.

Not that long ago, conventional wisdom on climate change held that all hydrocarbons needed to be eliminated. In his 2022 book How to Avoid a Climate Disaster Bill Gates pushed this view, warning that relying on natural gas as a “transition” fuel would support its use for too long to hit the UN’s Zero by 50 goal, which is widely regarded as unachievable.

In rejecting natural gas with its capability to displace far more harmful coal, Bill Gates aligned with that wretched little girl Greta and her band of poorly educated extremists in an otherwise thoughtful book.

Another example of the new appreciation is Terraform Industries, based in California and founded by Casey Handmer who was profiled recently in The World Ahead 2025, published by The Economist. Terraform is a start-up solar power company, which in itself is unremarkable. What sets them apart is their plan to use that solar power to produce synthetic natural gas.

The process derives hydrogen from water via electrolysis, adds CO2 and via a chemical reaction produces methane (CH4).

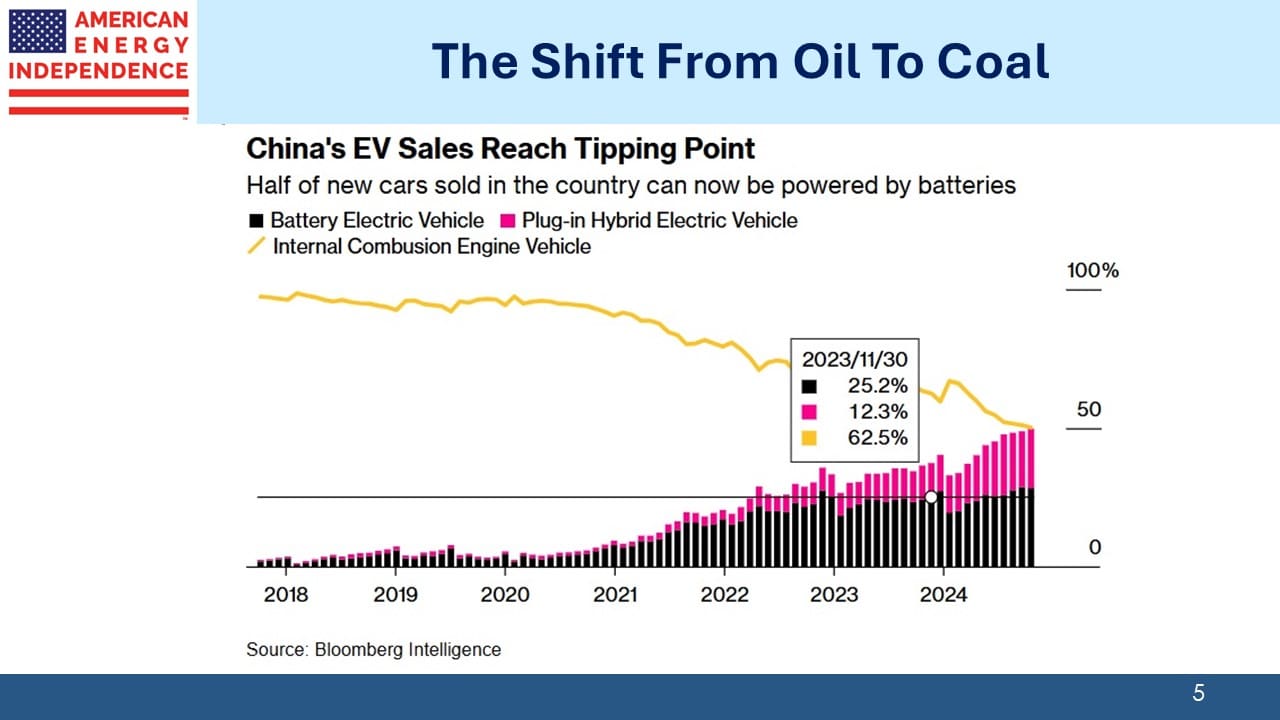

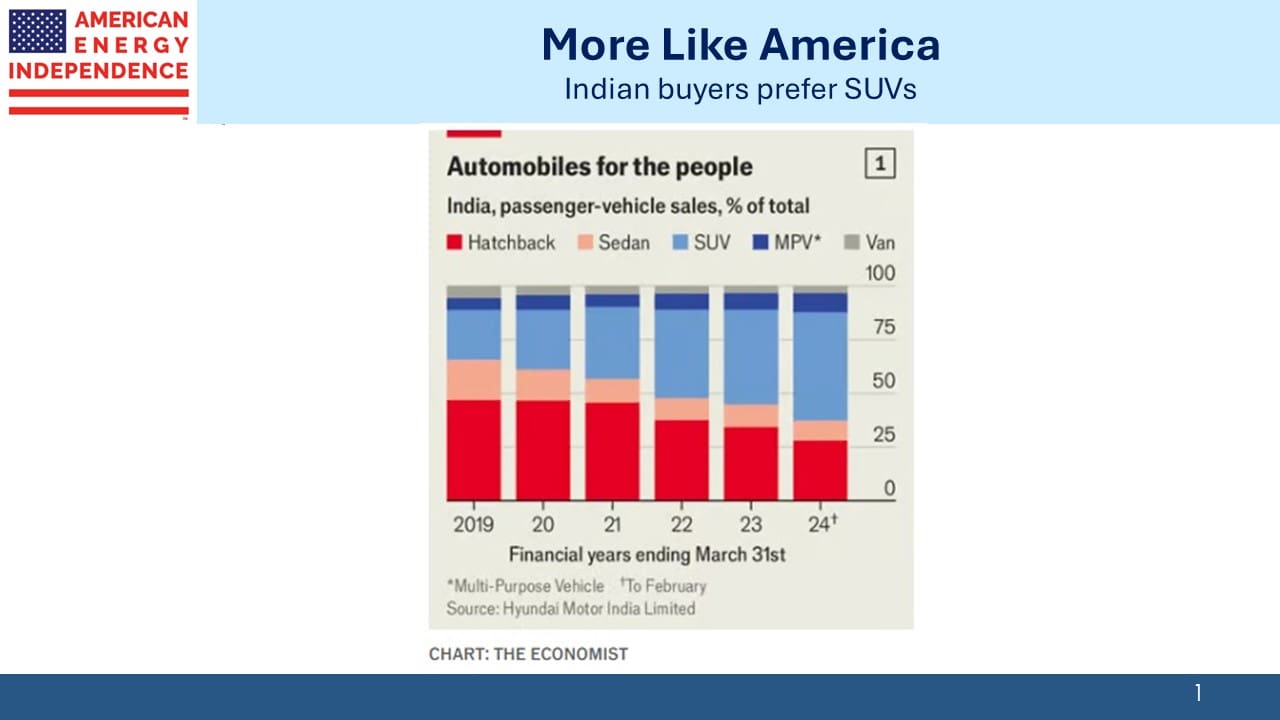

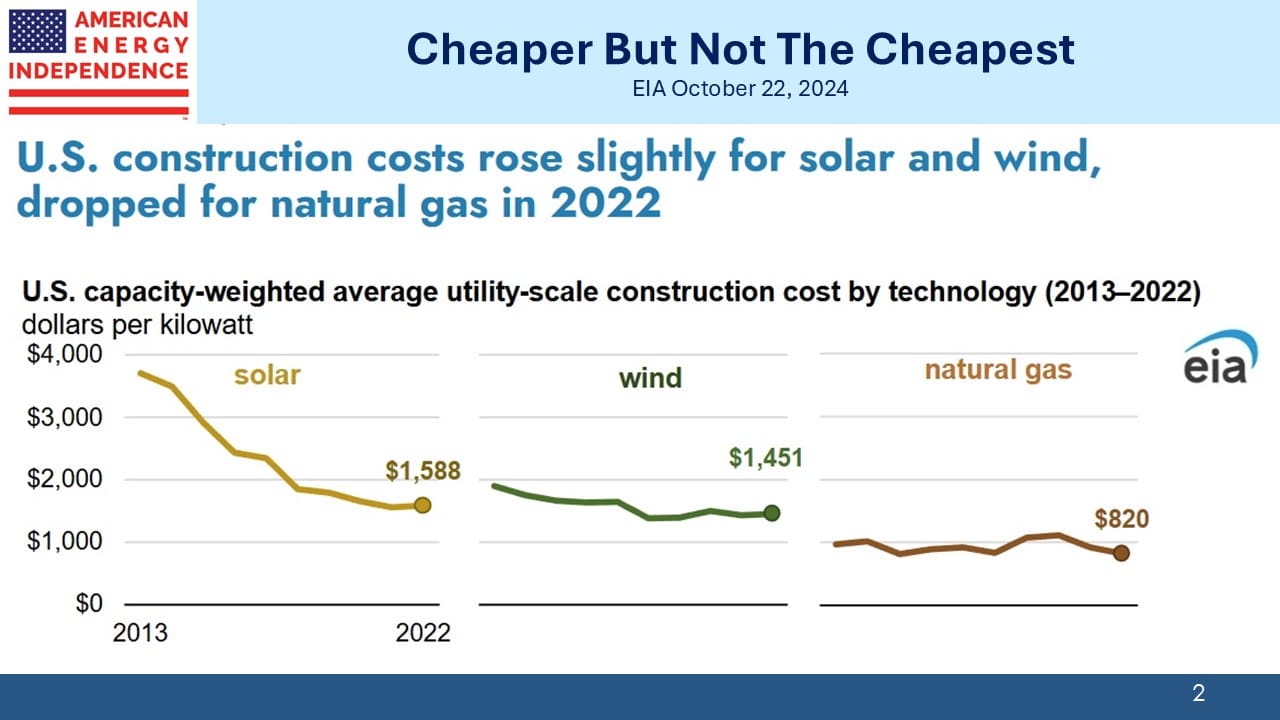

Terraform’s concept represents a remarkable shift. For years we’ve read that solar is the cheapest form of electricity, an assertion unsupported by the continued dominance of natural gas in power generation where it is around 40%. The efforts of climate extremists have been directed towards replacing natural gas with renewables such as solar.

Yet Divert and Terraform are two companies dedicated to producing natural gas confident that they’re aligned with efforts to reduce GHGs and combat climate change. They’re recognizing the importance of dispatchable energy, there whenever you need it, which is is how 80-90% of the world operates.

Divert is capturing methane that would otherwise be emitted into the atmosphere.

Terraform has decided that rather than trying to accommodate the debilitating intermittency of renewables, they should use them to create the reliable energy that the world wants.

It’s a remarkable evolution.

Terraform’s Handmer says, “We won’t rest until we’ve saturated the global market for any hydrocarbon at a price cheaper than fracking.” The natural gas they produce is $35 per Thousand Cubic Feet (MCF), a price he claims puts them, “in economic contention in many markets that rely on imported fuel.”

US natural gas currently trades at around $3 per MCF. LNG at benchmark delivery points in Europe and Asia is $14 per MCF. So it’s not obviously competitive just yet, although Terraform’s process can presumably operate wherever customers and sunshine co-exist. Perhaps when the distribution costs of regassifying LNG and moving it by pipeline to where it’s needed are figured, the economics start to look better.

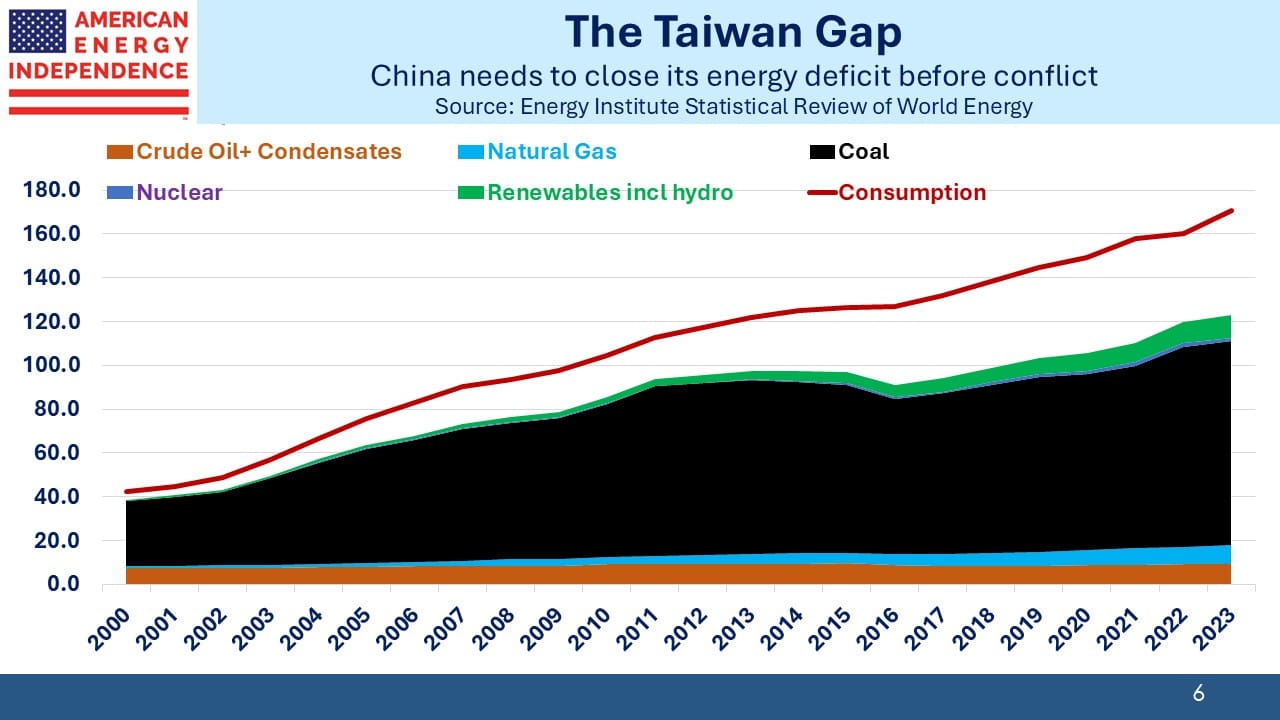

The efforts of these two American companies illustrate a growing trend of evolution towards lower-emission energy without destroying economic growth in the process. Both recognize the critical importance of reliable, secure energy. The vision of climate extremists and progressives has wrecked Germany for little tangible benefit.

As Enbridge CEO Greg Ebel says, coal was a 19th century fuel and oil a 20th century one. Natural gas is the 21st century fuel.

We have two have funds that seek to profit from this environment:

Energy Mutual Fund Energy ETF