Rising Rates Reflect Strong Pipeline Fundamentals

Will rising interest rates hurt pipeline company stocks? Ten year treasury yields are at 3.25%, a seven year high. The bond market is commanding the attention of equity investors once more.

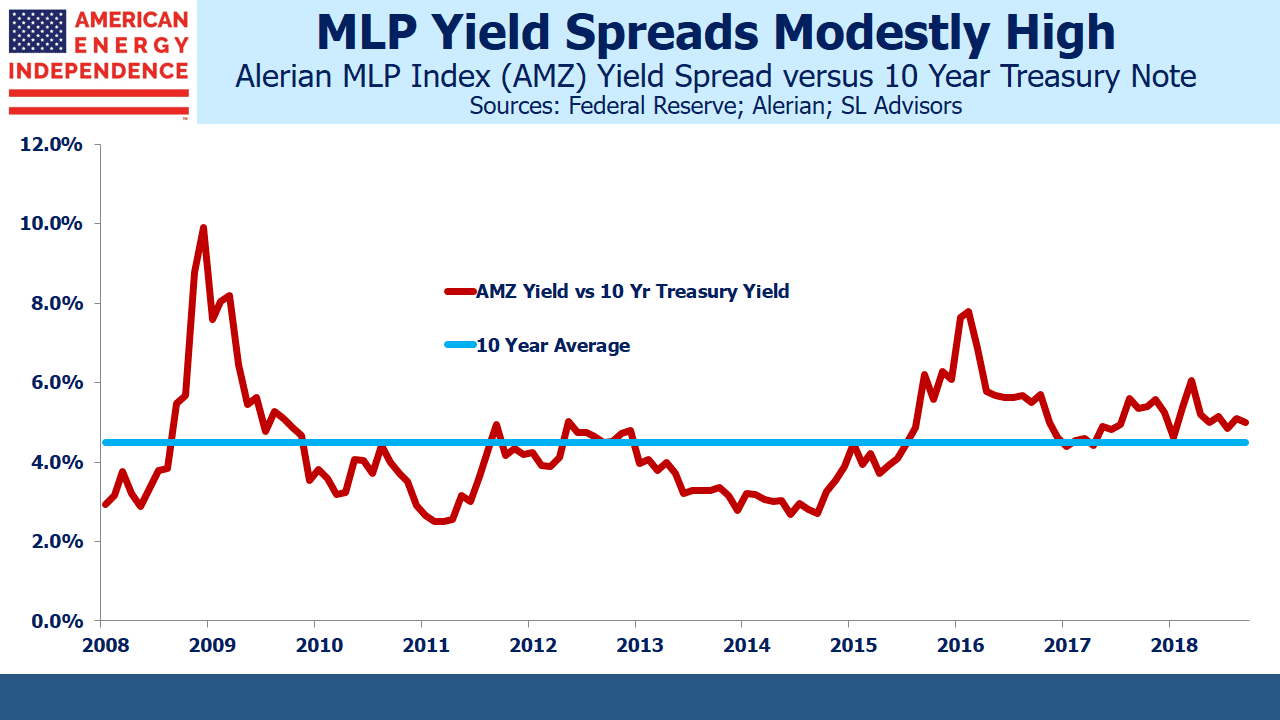

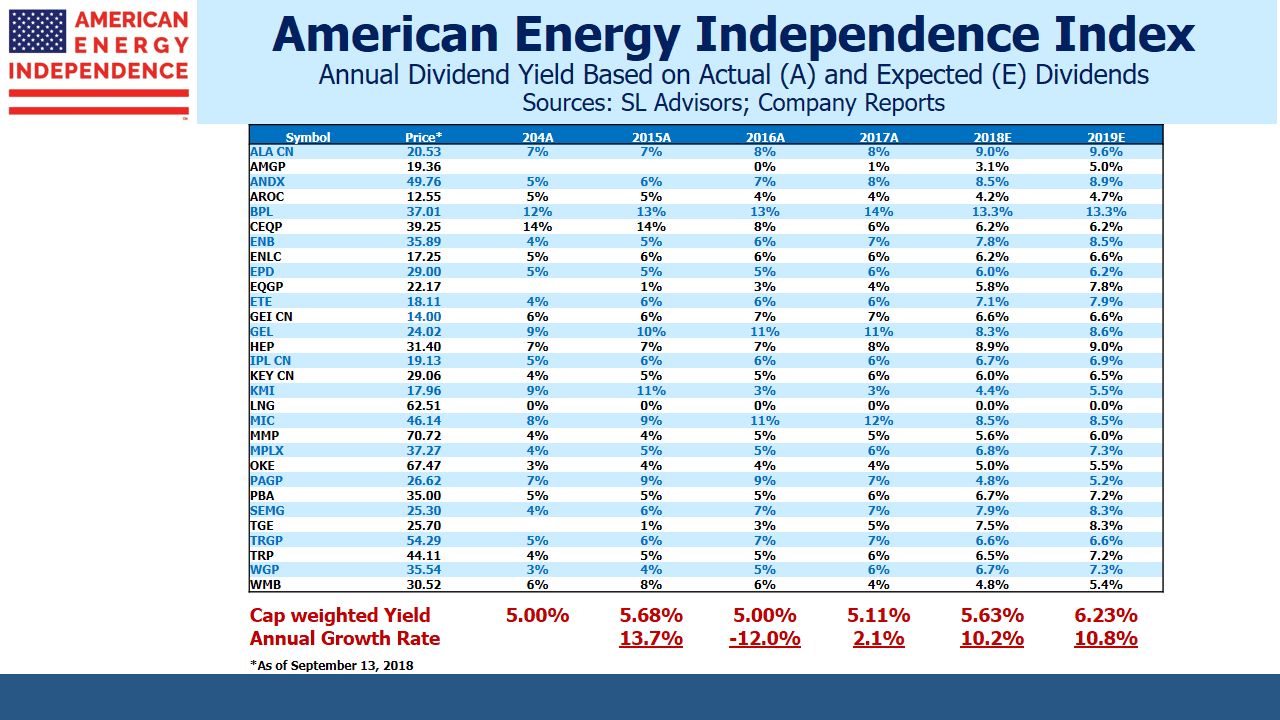

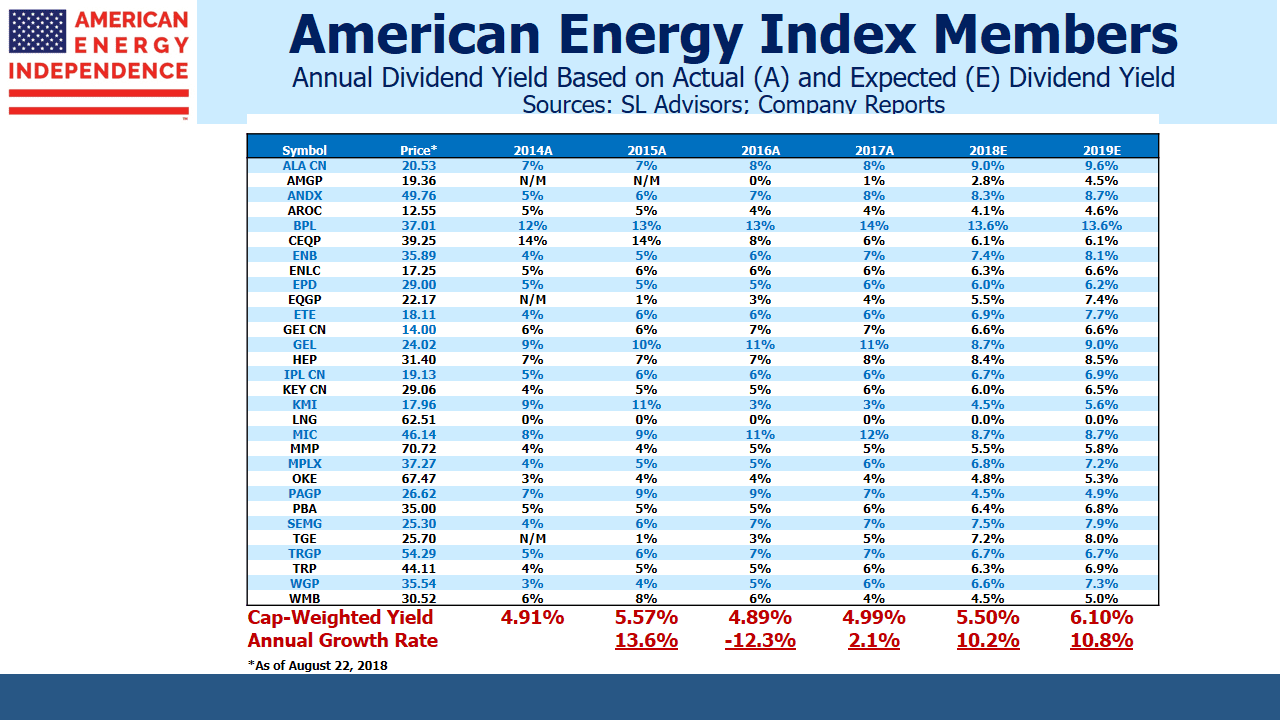

The high yields on MLPs have long attracted income-seeking investors. A common valuation metric is to compare the sector’s yield with the ten year treasury by measuring the yield spread. This is currently around 4.8%, compared with the twenty year average of 3.5%. In comparison, REITs and Utilities both have yield spreads under 1%.

While the MLP yield spread is historically wide, it’s been wider than average for almost five years, which probably means that the relationship has changed. Over the past decade it’s averaged 4.5%. MLP investors require a richer premium to other asset classes than in the past, which is why the bigger MLPs have been converting to corporations, so as to access a wider investor base (see Growth & Income? Try Pipelines).

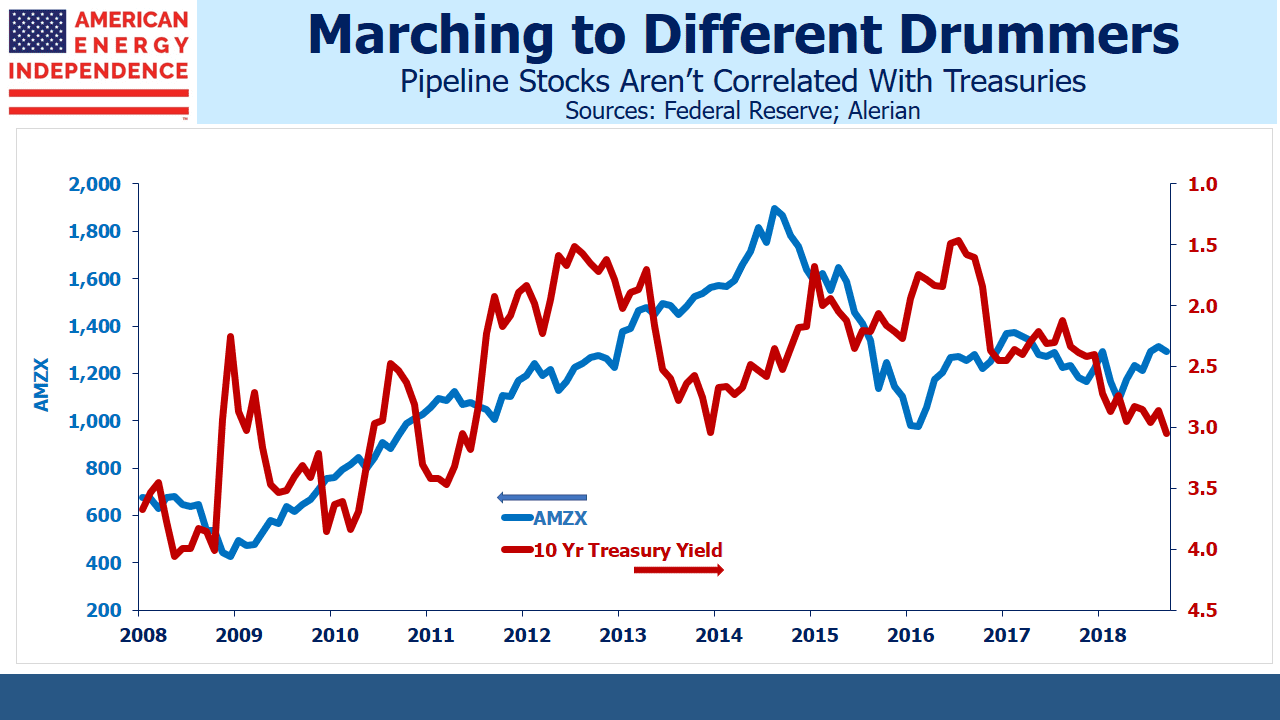

While MLP yields have remained stubbornly high, they continue to move independently of the bond market. Visually, energy infrastructure and ten year treasuries have no relationship at all. The correlation of monthly returns is -0.35 over the past decade and 0.16 over the past five years – practically speaking, there is no correlation between the two.

Over short periods of time, fund outflows from income alternatives can depress MLP prices, but the effect is rarely enduring. Tariffs on regulated pipelines often include an inflation escalator, allowing increases pegged to the Producer Price Index (PPI), which creates some inflation protection for pipeline owners if inflation was to spike higher. This is why we often tell investors that the impact of higher rates depends on whether inflation is rising or not. If rising inflation drives up yields, the higher PPI will feed directly into higher revenues where contracts are correctly structured.

However, if rates move up independently of inflation (i.e. higher real rates), then all assets are affected. Any investment is worth the sum of its future cashflows discounted at an appropriate interest rate. Pipeline stocks would likely be affected like many other sectors.

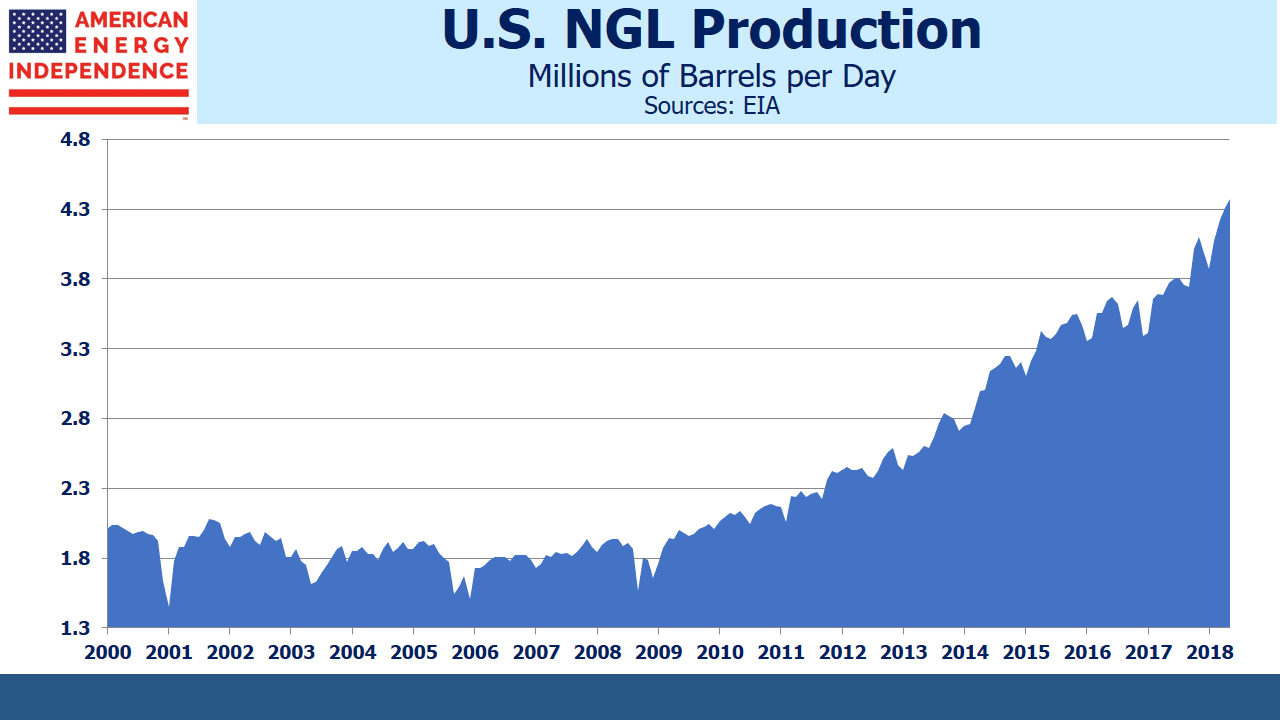

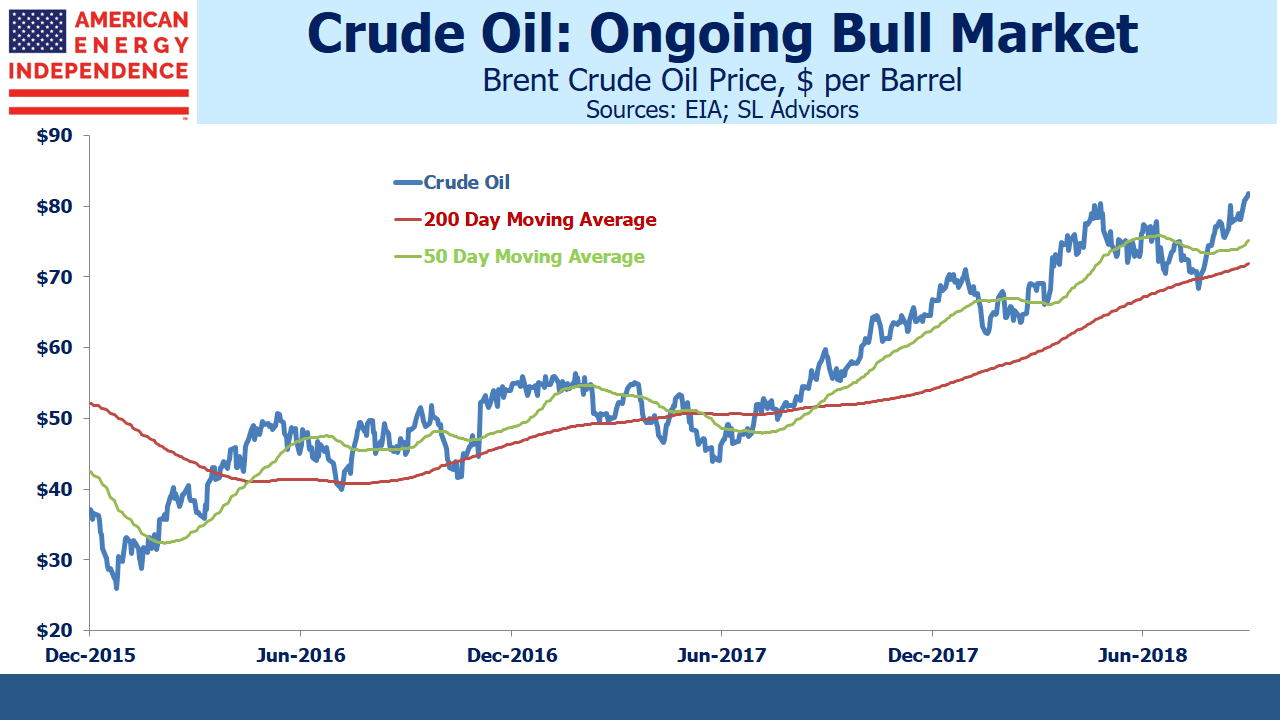

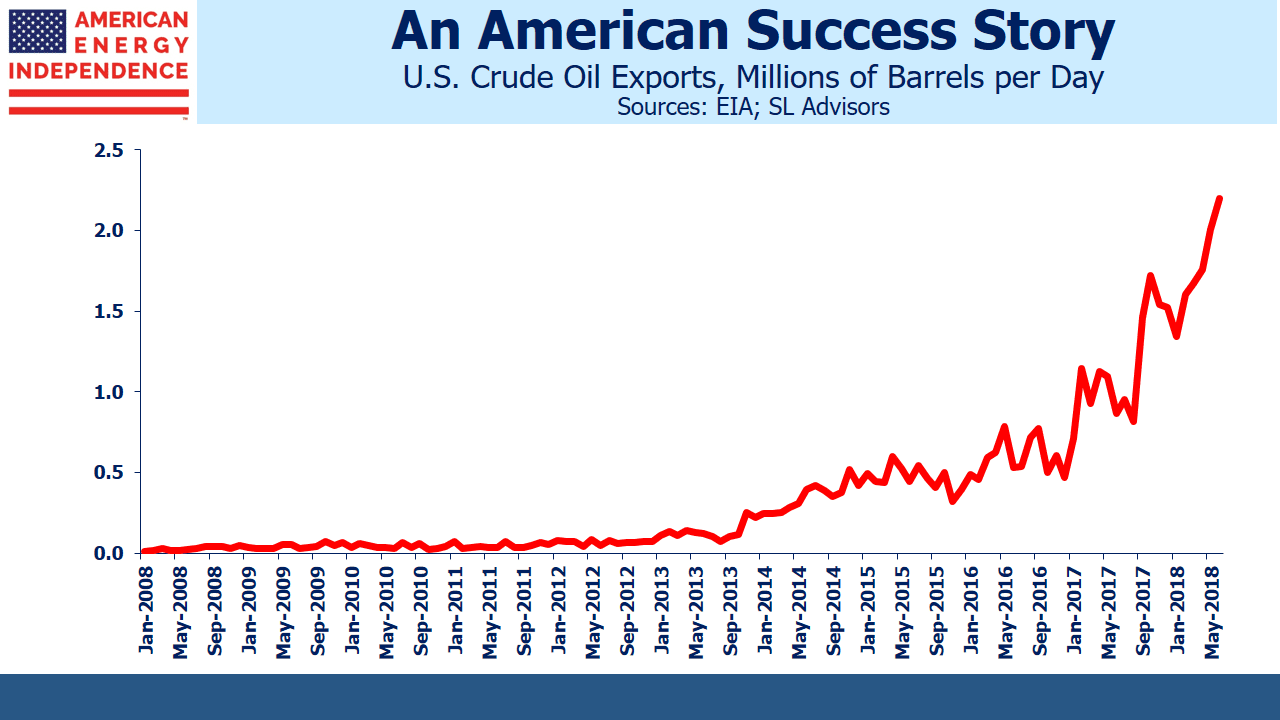

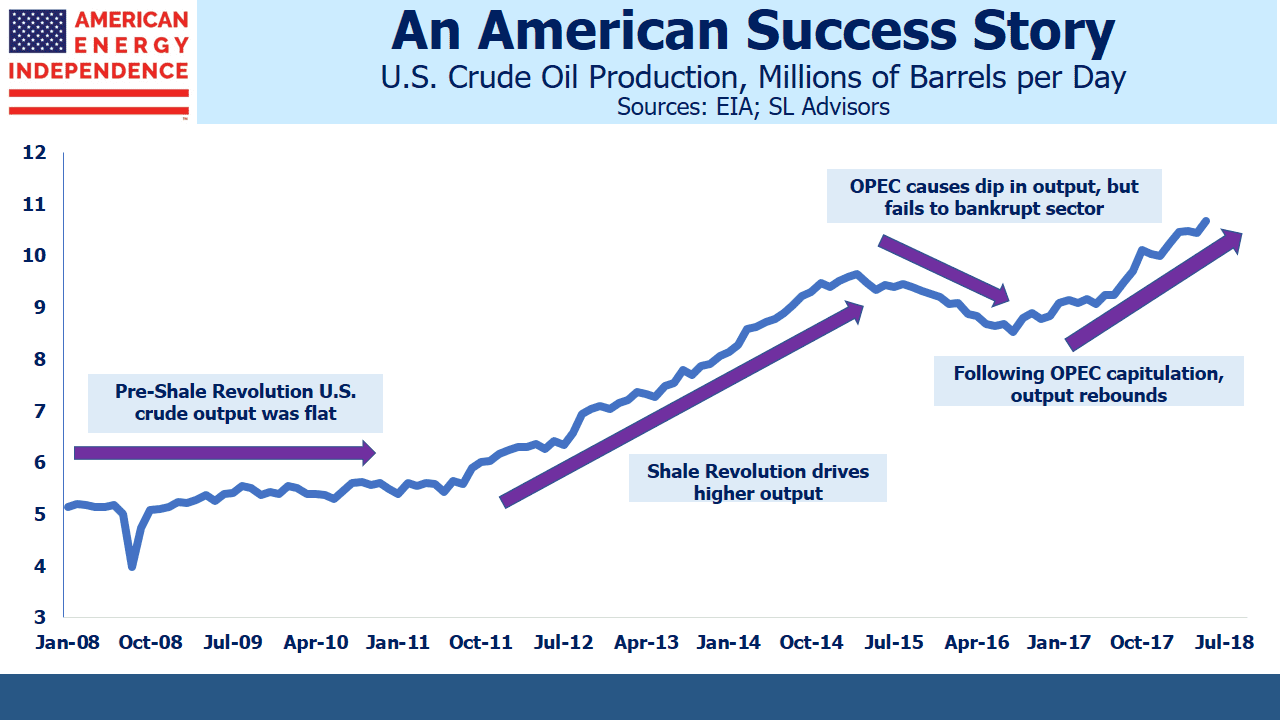

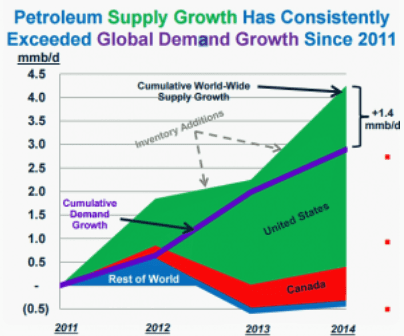

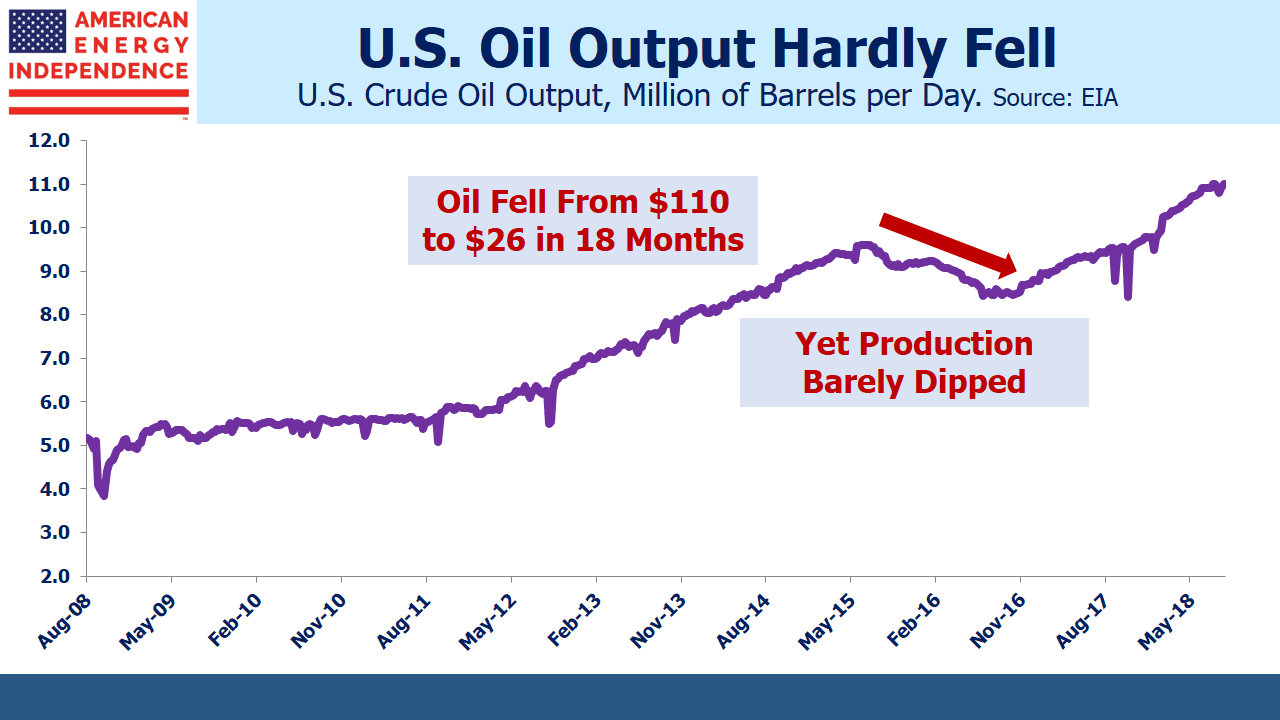

But economic growth is very strong, which mitigates the effect of rates. Unemployment is the lowest in living memory at 3.7%. Everyone who wants a job has one, and demand is up for many things including pipeline capacity. The U.S. recently became the world’s biggest crude oil producer (see America Seizes Oil Throne).

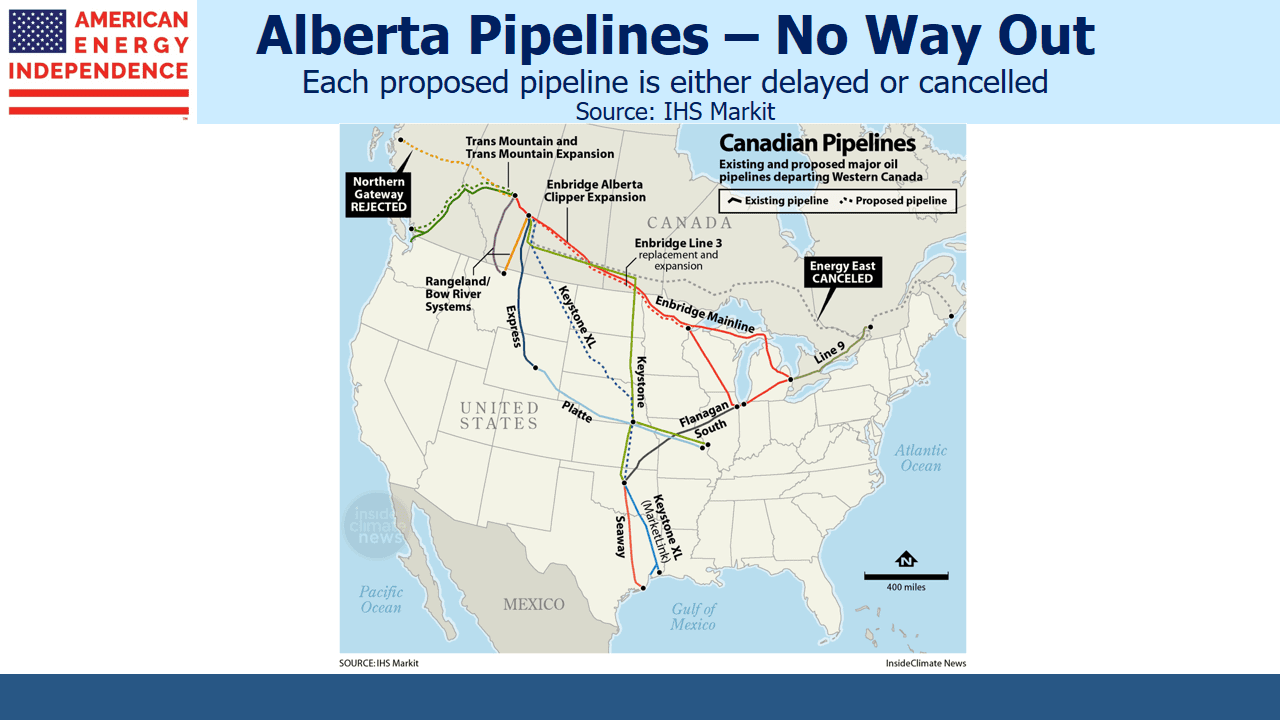

Permian volumes in west Texas are overwhelming available pipeline capacity, which led to a price discount on Midland crude versus the WTI benchmark of as much as $17 in summer. It’s recently narrowed to $7 – still more than the typical contracted pipeline tariff, but less than the $10-20 cost of truck transportation.

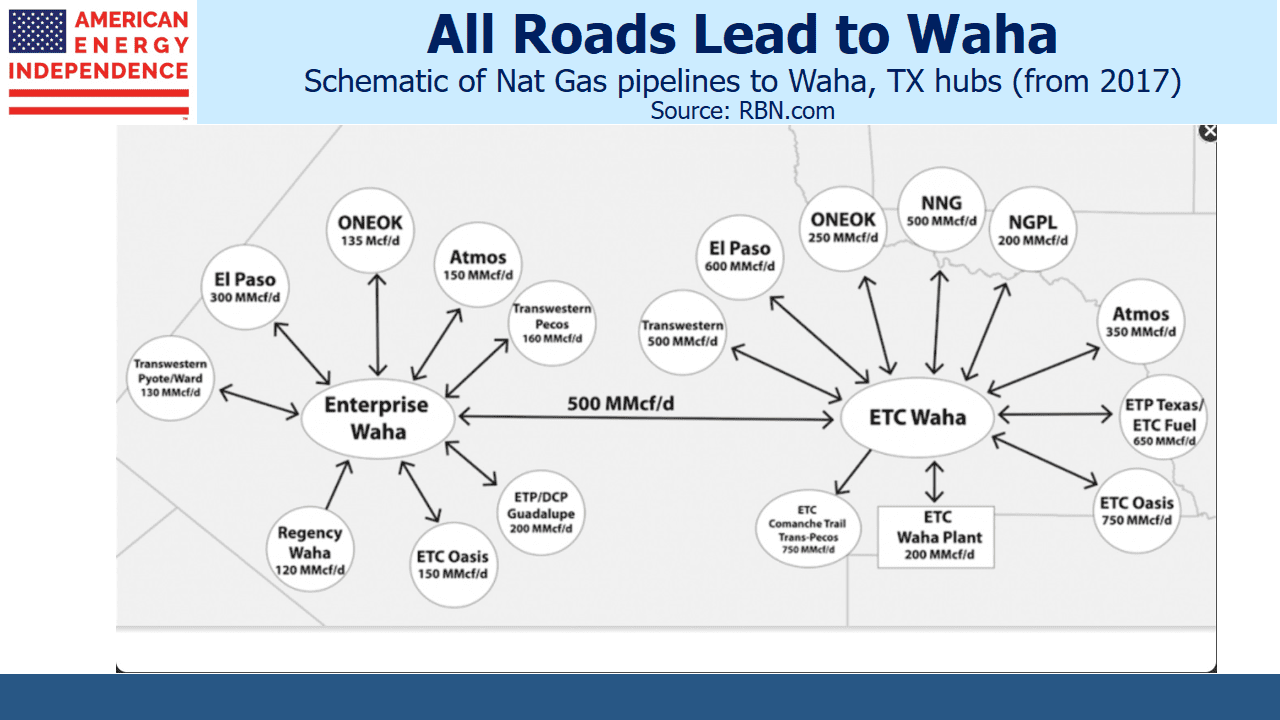

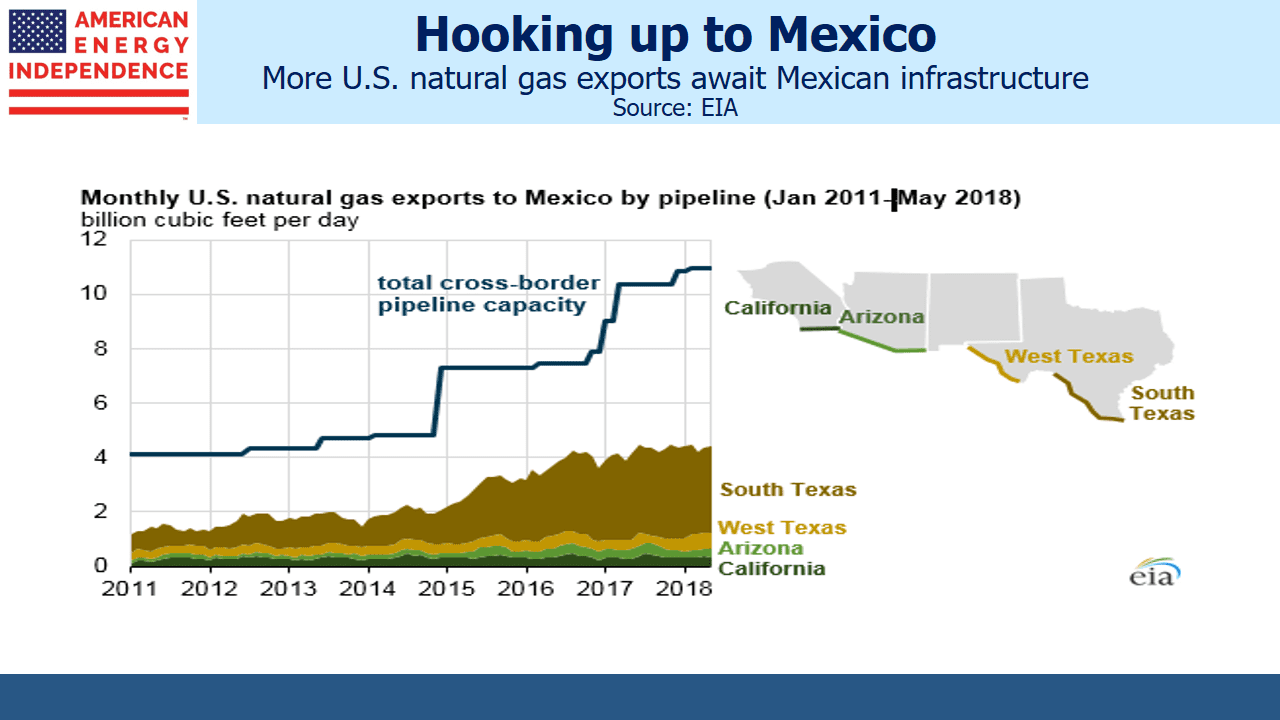

Natural gas currently trades at around $3 per Thousand Cubic Feet (MCF). The natural gas basis between Waha in West Texas and the Henry Hub benchmark location is $2, meaning Waha natgas is worth only $1 per MCF. Permian gas output is 10 Billion Cubic Feet per Day (BCF/D), whereas pipeline capacity is only 8 BCF/D. Some of this excess production is flared, meaning it’s worth zero.

Unlike crude oil, natural gas can’t easily be moved by rail or truck because of the pressure required to compress it. Pipelines are the only option, and the price discount persists because the takeaway infrastructure isn’t available.

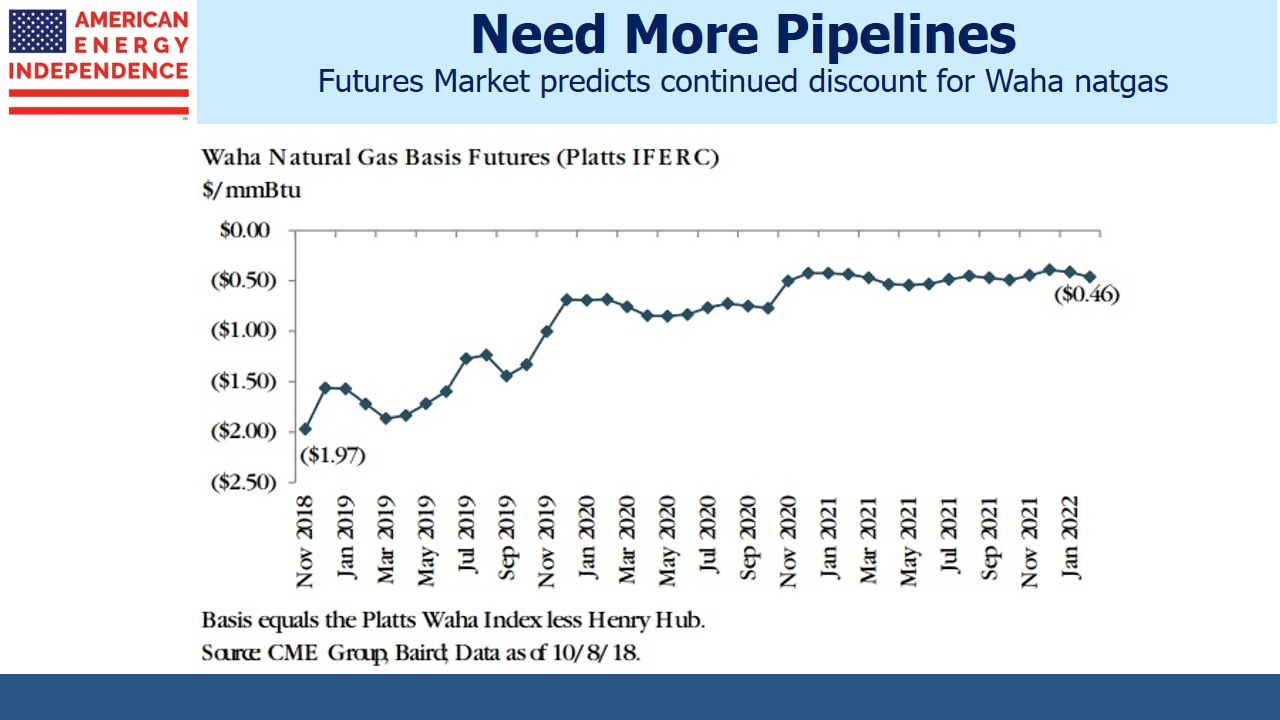

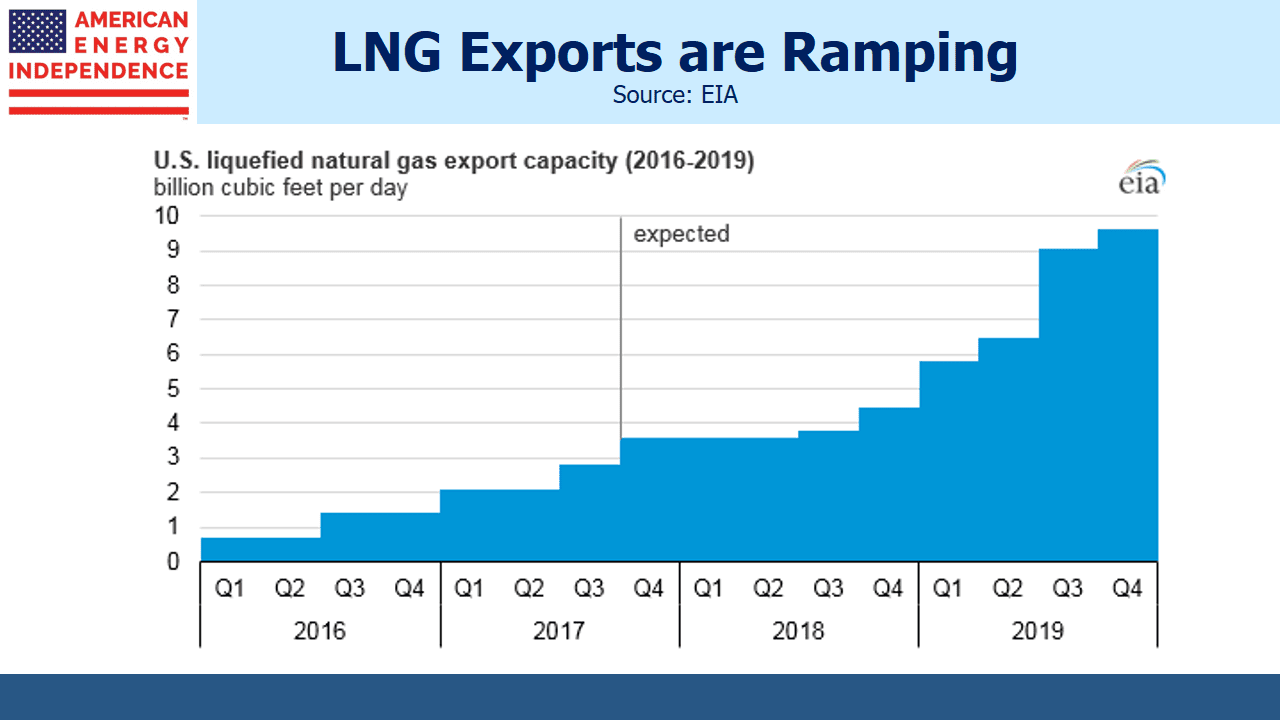

Anticipated Mexican demand is awaiting completed infrastructure south of the border. Futures traders expect the discount to persist for a while longer, which should benefit Kinder Morgan (KMI), Energy Transfer (ETE) and Oneok Inc (OKE). Beginning in 2020, additional capacity will be made available via KMI’s Gulf Coast Express and Permian Highway pipelines, adding around 4 BCF/Day.

Natural gas production is going to keep growing. Shell recently told investors they expect 2% annual growth through 2035, twice the growth in global energy demand overall. Although natural gas is often touted as being a bridge to a world of renewables, another energy executive said, “Gas not a transition fuel, but a destination fuel.”

The point is that these price differentials, which reflect unmet demand for additional pipeline capacity, are unlikely to be harmed by a modest rise in interest rates. The bond market is under pressure because the economy is booming.

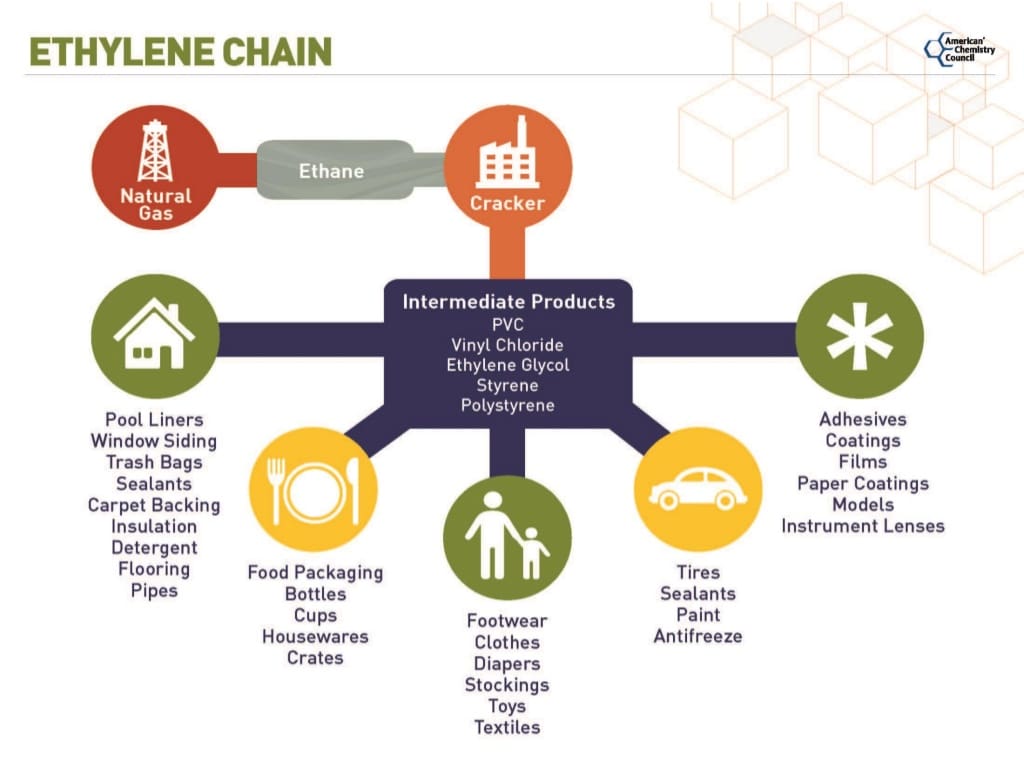

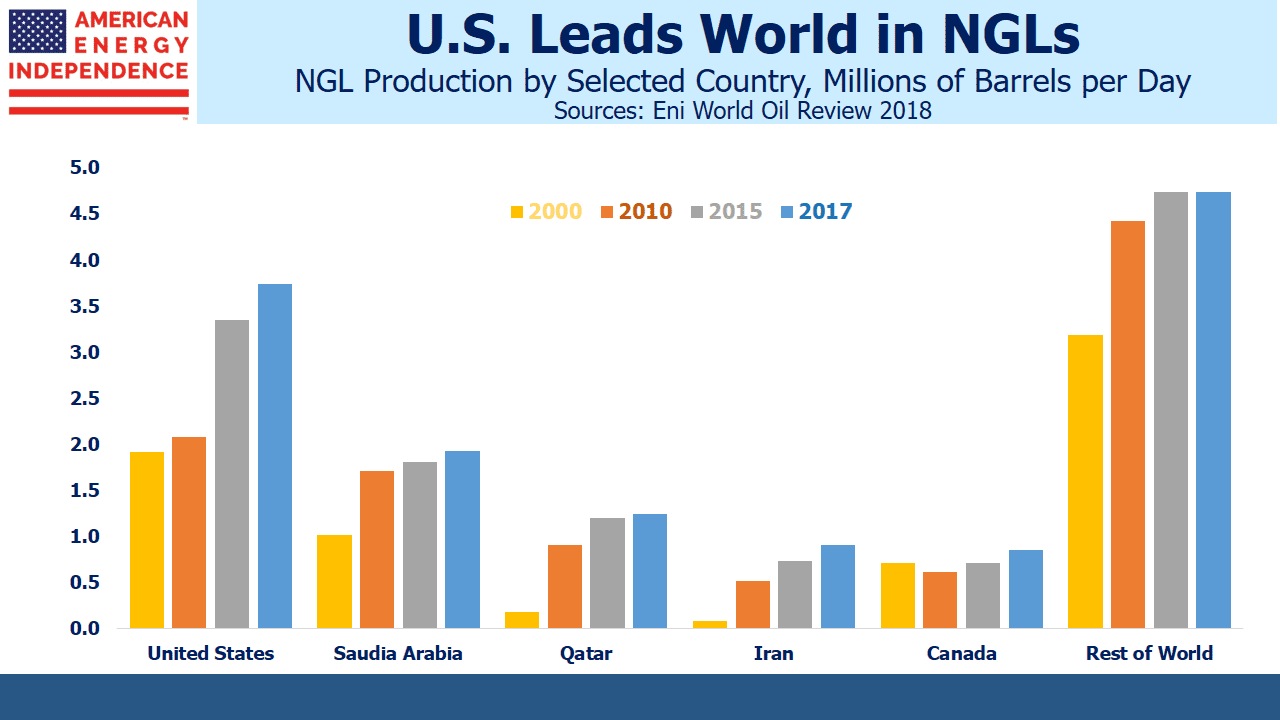

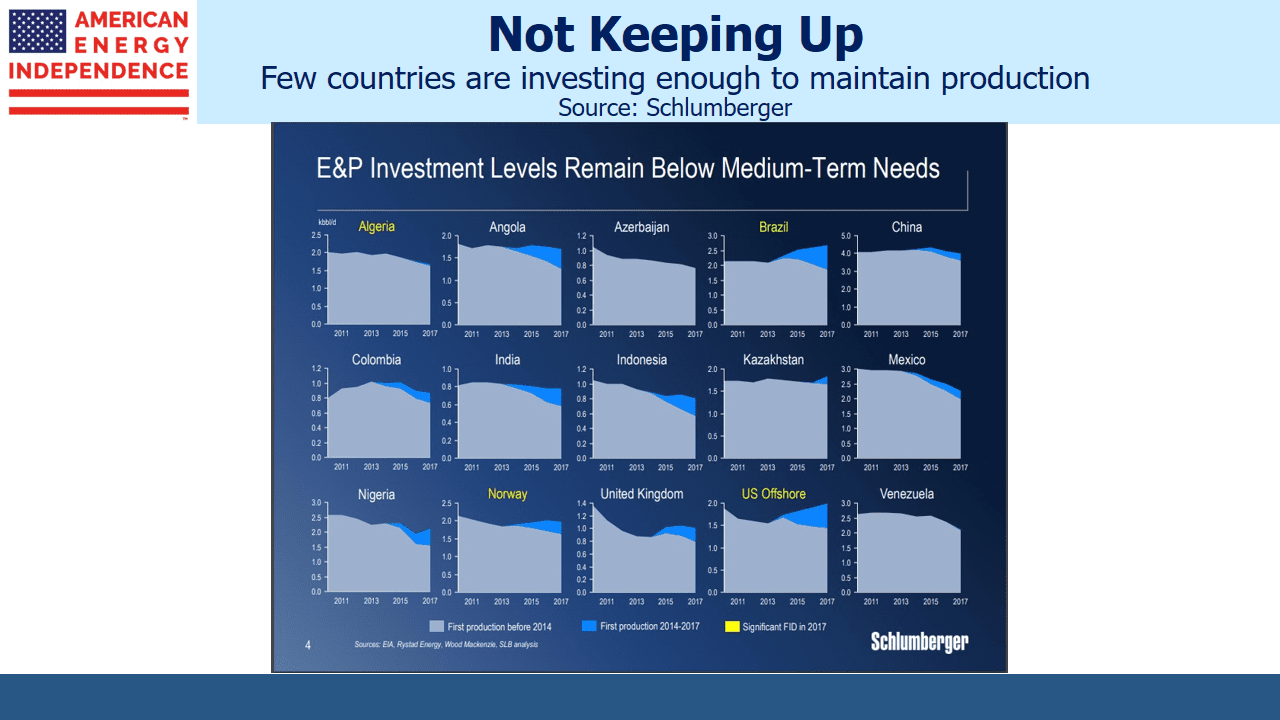

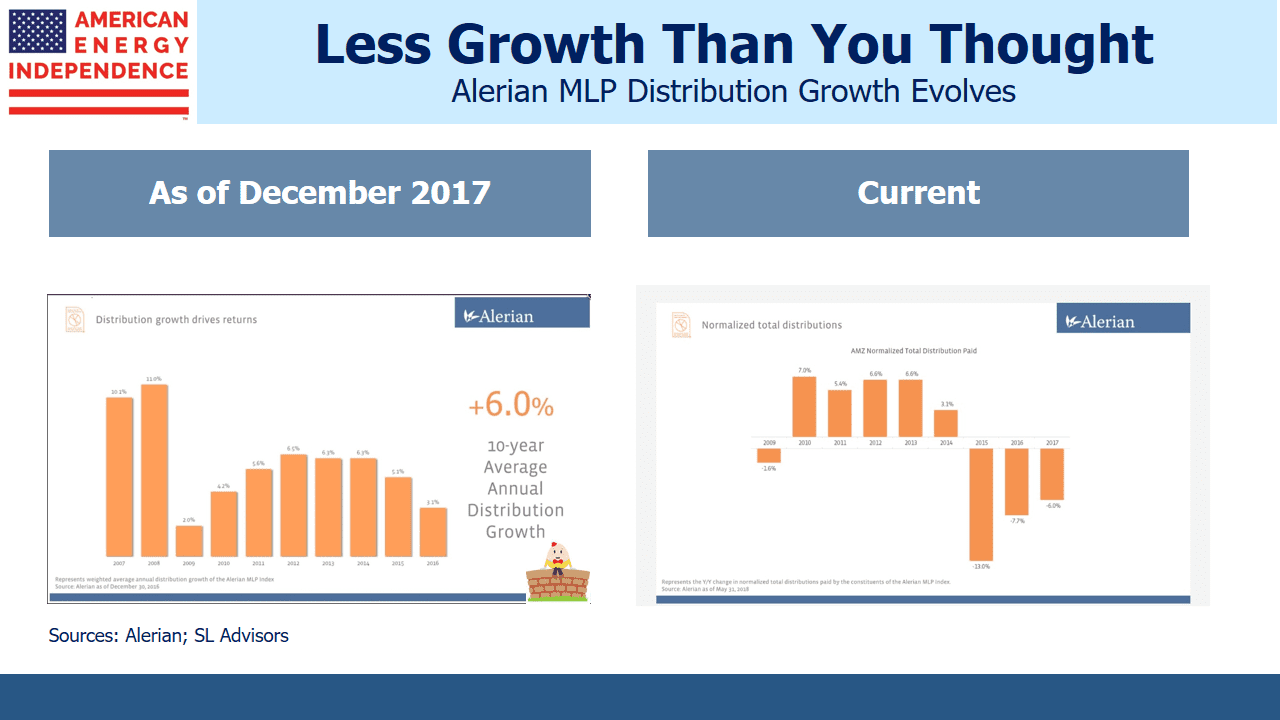

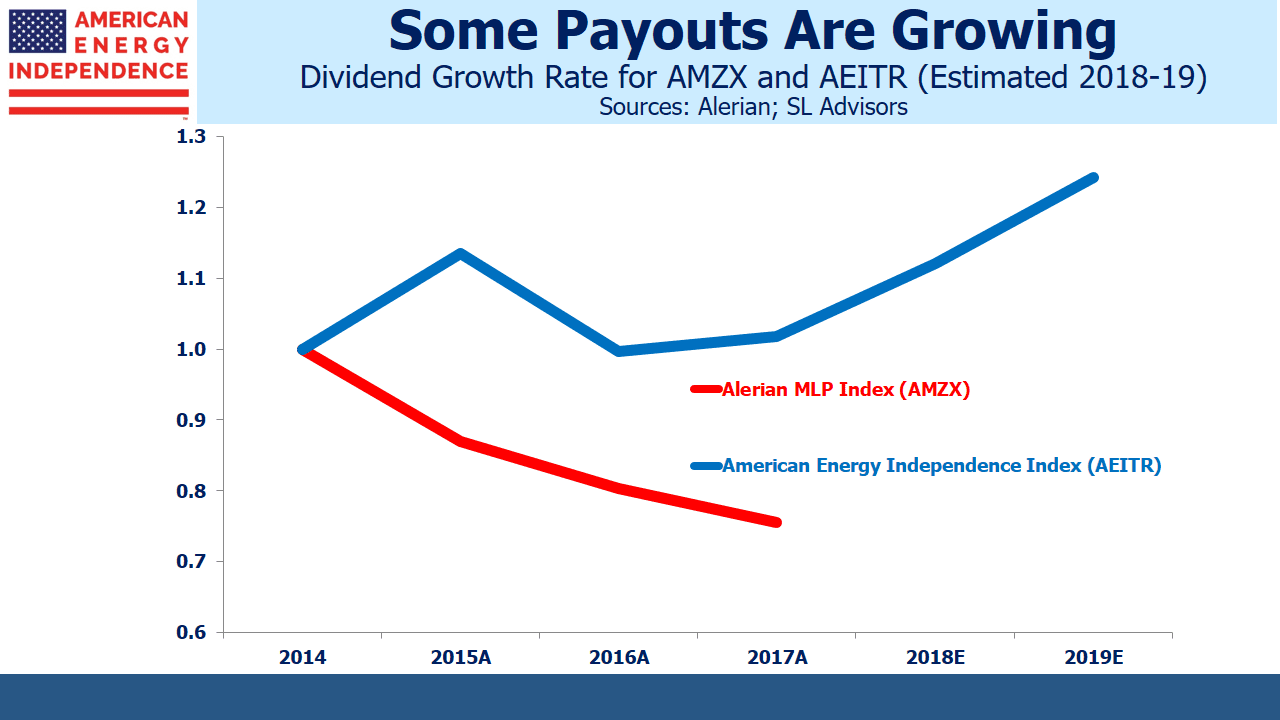

Moreover, today’s battle-hardened MLP investors have endured several dozen MLP distribution cuts. The secular growth in U.S. hydrocarbon production is what attracts them (see Can Anyone Catch America in Plastics?). The companies themselves have also changed, with many of the biggest abandoning the MLP structure to become corporations (see The Uncertain Future of MLP-Dedicated Funds). As a result, broad energy infrastructure is less reliant on MLP investors (often older, wealthy Americans). The adoption of a corporate form, widely followed by the biggest MLPs and most recently by Antero Midstream GP (AMGP) has resulted in a broader, more institutional investor base.

The bottom line is that there’s little reason to fear the current rise in interest rates. Historically, there’s no statistical relationship between bonds and pipeline stocks. Output of oil, gas and natural gas liquids is rising, fueling demand for infrastructure. And the investor base is probably the broadest it’s ever been, as companies move away from the fickle MLP investor towards more conventional holders of U.S. equities. The broad-based American Energy Independence Index, which includes the biggest U.S. and Canadian energy infrastructure stocks, is up almost 2% in October even with treasury yields up 0.20%. So far, the sector has not been impacted by the headlines around rising rates.

We are long AMGP, ETE, KMI and OKE