How Occidental Invests In Lower Taxes

Occidental Petroleum (OXY) has a checkered history. In 2019 CEO Vicki Hollub snatched Anadarko away from Chevron (CVX), who already had a signed deal in place. CVX CEO Mike Wirth showed financial discipline that’s rare in such cases and declined to get into a bidding war. Instead, they walked away with a $1BN break-up fee.

Hollub obtained $10BN in financing from Berkshire in the form of preferred shares in order to close the deal. Perhaps Buffett also had doubts about the price OXY was paying, since he chose to avoid the common in favor of a more secure return. Covid soon struck, and the energy sector plummeted. Within a year of OXY’s audacious purchase crude oil was trading at negative prices as demand collapsed under the regime of lockdowns.

By April 2020 OXY’s stock had lost 80% of its value prior to the Anadarko deal. Although the Covid collapse was to blame, CVX had dropped by just over half. It looked as if Vicki Hollub had been outplayed by a competitor with financial discipline and devastatingly unlucky timing.

The energy sector began its slow recovery, but OXY lagged and by October 2020 was making new lows, down 85% from its pre-deal level while CVX was steadily recovering.

Since then, the gap has narrowed. Buffett evidently liked what he’s learned about OXY since he recently obtained regulatory approval to buy up to half of their common stock. Berkshire’s market outperformance this year has drawn quant funds. One investment manager believes Berkshire will eventually buy the whole of OXY, becoming an oil major in its own right.

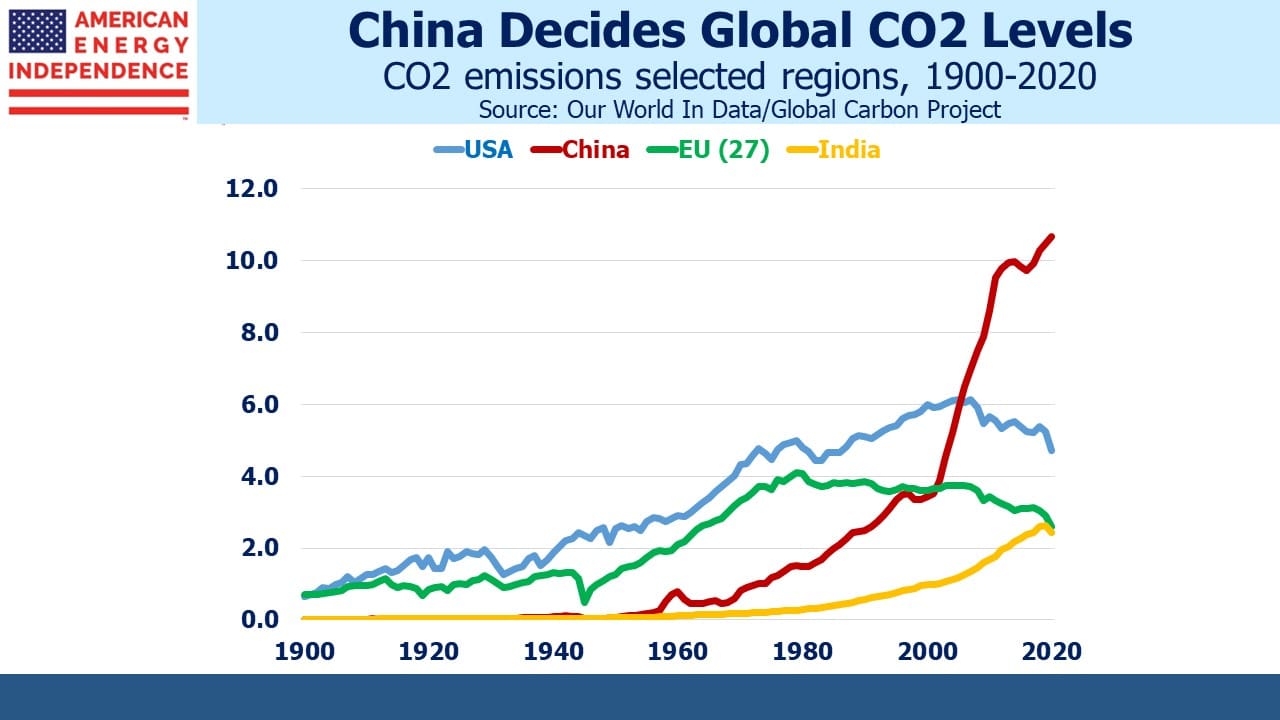

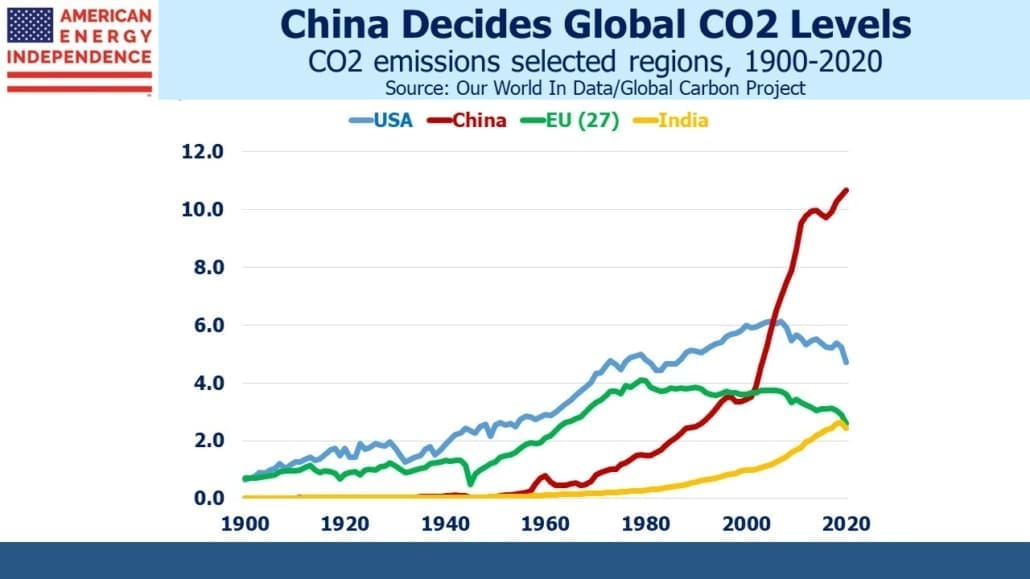

OXY’s value lies in its reserves of oil and gas. But energy companies have accepted the energy transition and have initiatives aimed at showing they’re going to be part of the solution to CO2 emissions. Recently OXY announced plans to develop the world’s biggest Direct Air Capture (DAC) facility to remove CO2 from the ambient air.

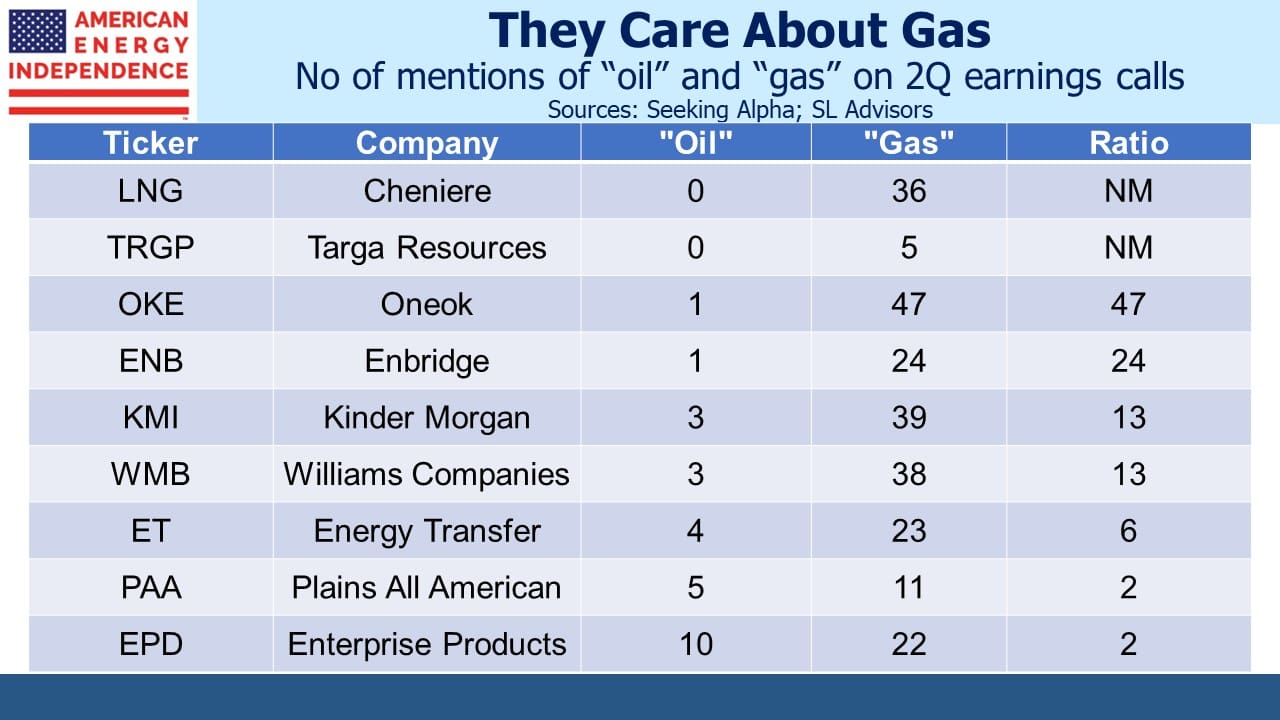

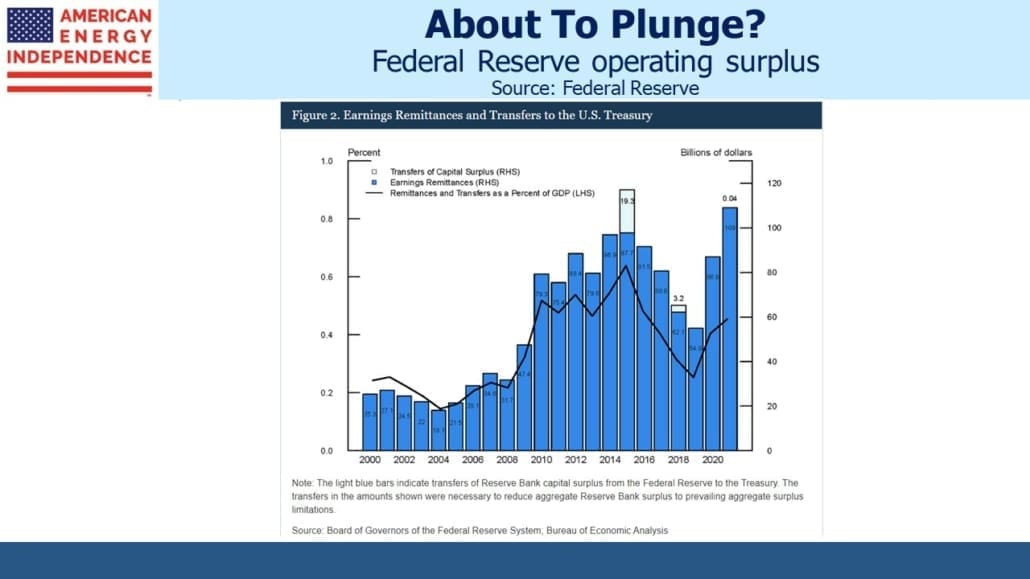

Carbon Capture and Sequestration (CCS) received a boost in the recent Inflation Reduction Act (IRA). The 45Q tax credit starts at $85 per Metric Tonne (MT) for CO2 that is permanently sequestered underground. Enhanced Oil Recovery (EOR) has long relied on pumping CO2 into mature wells where the pressure has dropped, to force up more oil. The technology is reasonably well understood, and while burying CO2 to produce more fossil fuels doesn’t reflect the spirit of emissions reduction, it can be buried in other secure geological formations. Kinder Morgan has the most extensive CO2 pipeline network in the US because of their EOR business. Several pipeline company executives expressed optimism that they could benefit from the 45Q tax credit.

CCS makes the most sense where CO2 emissions are high – such as the exhaust of coal-burning power plants. But it has its critics. Robert Bryce recently reprised his 2009 criticism of CCS in response to the IRA. He noted that coal burning power plants lose up to 28% of their output when their emissions are being captured. He also warned that pipelines required to move CO2 to its final burial would likely have to be funded by taxpayers. And he estimated that capturing half of the 5.4 billion MTs of CO2 generated in the US annually would mean handling a volume of gas, even compressed to 1,000 pounds per square inch, equivalent to daily global oil production. He warns, “We would need to find an underground location (or locations) able to swallow a volume equal to the contents of 41 oil supertankers each day, 365 days a year.”

In JPMorgan’s 2022 Annual Energy Paper, Michael Cembalest estimated that capturing 15-20% of US CO2 emissions would involve handling a volume of gas exceeding all US production – a more modest estimate than Bryce’s but still staggeringly high.

OXY’s planned DAC facility is seemingly going after an even harder problem. The concentration of CO2 in ambient air (ie not standing downwind of a power plant) is around 412 parts per million. You have to process enormous quantities of air to get much CO2. OXY expects its CCS plant in Ector County, TX to capture 0.5 MT annually with the capability to reach 1 MT. The CO2 will be buried in a formation beneath forest land owned by paper company Weyerhauser. Trees are nature’s carbon capture, but the CO2 is eventually released when the tree dies or burns down.

OXY’s subsidiary 1PointFive (named in reference to the goal of limiting global warming by 1.5° C versus 1850) hopes to have 70 DAC facilities operational globally by 2035. The IRA provides up to $180 per MT tax credit for DAC. Five of the plants planned by 1PointFive in the US operating at 1 million MTs per year would generate $900 million in tax credits, significantly reducing OXY’s tax bill.

Buffett probably expects crude oil demand to remain strong for many years, supported by rising living standards in emerging economies. With enough DAC facilities in place, OXY investors could profit from providing energy the world wants and from mitigating its effects. It’s the kind of two for one deal the Oracle likes.

We have three funds that seek to profit from this environment:

Energy Mutual Fund Energy ETF Real Assets FundPlease see important Legal Disclosures.