The Hard Math Of The Energy Transition

/

Getting to zero emissions by 2050, the goal set by the UN in order to limit global warming to 1.5° C above pre-industrial times, is technically well within reach. Not with intermittent solar panels and windmills – extracting all the minerals necessary for their manufacture plus enormous battery back-up in implausible. Kinder Morgan’s enhanced oil recovery process pumps CO2 into mature oil wells to push out additional crude. This is Carbon Capture, Use and Sequestration (CCUS). The CO2 emitted by power plants, cement and steel factories and other industrial users can also be captured for permanent burial without being used (CCS).

There is reported to be bipartisan support for a CCS tax credit of up to $150 per metric tonne (MT), a level many in the industry believe would spur investment in the necessary infrastructure. The US emits just under 5 Billion Tonnes (BT) of CO2 from fossil fuel combustion annually. As a simple example, assuming transportation went fully electric, swapping gasoline for natural gas to produce more electricity, at $150 per MT we’d spend $750BN eliminating energy-related CO2. This is just under 4% of GDP, roughly the same as our defense budget.

JPMorgan estimates that to sequester 15-20% of US CO2 emissions via CCS would require moving 1.2 billion cubic meters of CO2 – more volume than US crude oil production. This would require a lot of new infrastructure.

Direct Air Capture (DAC) removes CO2 from the air. This is another technically feasible strategy, especially if the world misses the UN’s goal and needs to remediate. Although one might think the atmosphere is swollen with CO2, it’s currently around 412 parts per million, or 0.0412%. This relatively low concentration means a lot of air needs to be processed to remove a MT of CO2. By contrast, power plant emissions range from 1-15% CO2 and chemical/industrial plant emissions are from 20-95%.

JPMorgan recently published a research paper examining prospects for DAC. There are two main technologies, one using a liquid and the other a solid which bind to the CO2 in air passed over them. Climeworks operates a prototype facility in Switzerland. DAC uses energy. JPMorgan estimates 4.9GJ per MT of CO2 removed, or 1.37 Megawatt Hours (MwH).

To put this in perspective, if the US chose to remove the 5 BT of energy-related CO2 released annually, this would require 6.8 Terawatt Hours (TwH) of electricity. We currently generate 4.1 TwH – and if this 6.8 TwH of additional electricity wasn’t generated from 100% renewables there would be further CO2 capture required.

JPMorgan estimated a range of costs for DAC of between $191 and $454 per MT. At some scale the price could be at the low end of the range but could also exhaust availability of critical inputs, increasing costs.

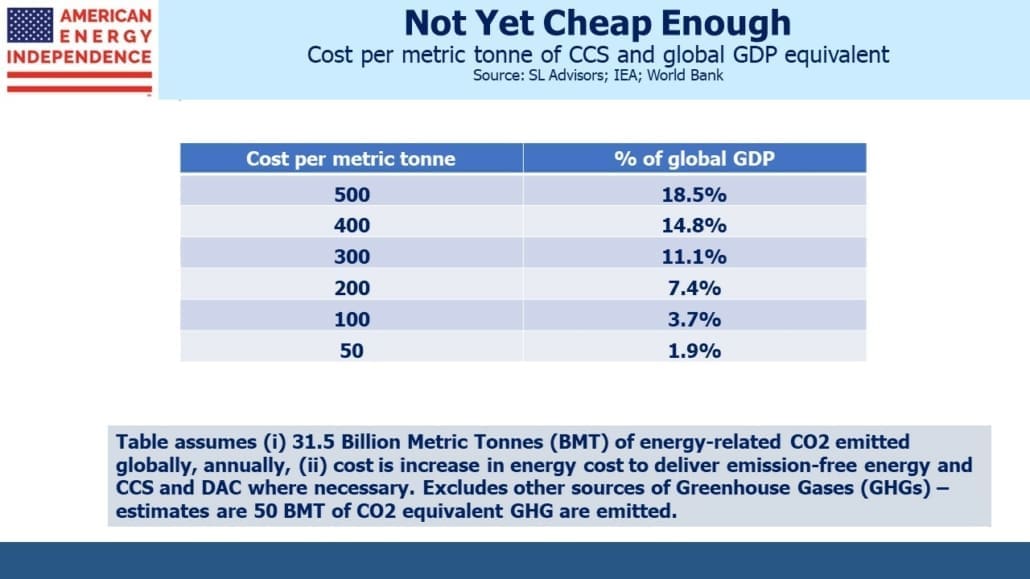

The table shows the cost in terms of global GDP of removing the 35 BT of energy-related CO2 that’s emitted. None of the figures are politically acceptable in today’s environment. Even at $50 per MT it would be just under 2% of global GDP.

Note that this analysis only considers the 35BT of energy-related CO2 emitted globally. Total emissions of Global Greenhouse Gases (GHG), including methane, are estimated at 50 BT CO2 equivalent.

This also assumes the world relies fully on capturing CO2 to reach the “Zero by 50” UN goal. Increased use of renewables, coal-to-gas switching, much more nuclear power and development of hydrogen are all being pursued to varying degrees. The EU trading system for carbon permits currently prices CO2 emissions at around €90 (US$94.50) per MT. This can be thought of as the low end of the range of cost to reach Zero by 50 because current trends and policies suggest we’re not on that path. Applied globally, that is equivalent to 3.5% of GDP just to remove our energy-related CO2 emissions.

There is lots of innovation going on. For example, NextDecade estimates that they can provide CCS services at a cost of $57 per MT (before financing). Given the financial payoff for technologies that can reduce or eliminate emissions cheaply, we should expect plenty of positive surprises.

Carbon taxes, tax credits and permits provide a rough guide to the low end of the range of cost involved in transitioning to zero-emission energy. They’re generally set at a level needed to at least partially subsidize renewables, or to impose an appropriate cost on emissions, depending on your view. They need to be high enough to induce behavioral change.

Their cost reflects the ability of clean technologies to replace our current energy systems. The cost of carbon can also be thought of as incorporating the probability that we’ll achieve substantially reduced CO2 levels. A falling cost would indicate improving competitiveness of alternate energies.

That isn’t happening, at least not yet. There is no indication that the world is willing to spend anywhere close to 3.5% of GDP in fighting climate change. US gasoline prices are relatively low compared with most other countries, and yet their rise this year prompted the Administration to blame Covid, Putin and just about everything other than their own policies while symbolically releasing crude from the Strategic Petroleum Reserve.

There is little public support for paying more for energy. Which means that the most likely outcome is continued growth in the consumption of all kinds of energy; modest gains in market share for intermittent solar and wind; and learning to cope with a warmer planet.

We have three funds that seek to profit from this environment:

Please see important Legal Disclosures.

Important Disclosures

The information provided is for informational purposes only and investors should determine for themselves whether a particular service, security or product is suitable for their investment needs. The information contained herein is not complete, may not be current, is subject to change, and is subject to, and qualified in its entirety by, the more complete disclosures, risk factors and other terms that are contained in the disclosure, prospectus, and offering. Certain information herein has been obtained from third party sources and, although believed to be reliable, has not been independently verified and its accuracy or completeness cannot be guaranteed. No representation is made with respect to the accuracy, completeness or timeliness of this information. Nothing provided on this site constitutes tax advice. Individuals should seek the advice of their own tax advisor for specific information regarding tax consequences of investments. Investments in securities entail risk and are not suitable for all investors. This site is not a recommendation nor an offer to sell (or solicitation of an offer to buy) securities in the United States or in any other jurisdiction.

References to indexes and benchmarks are hypothetical illustrations of aggregate returns and do not reflect the performance of any actual investment. Investors cannot invest in an index and do not reflect the deduction of the advisor’s fees or other trading expenses. There can be no assurance that current investments will be profitable. Actual realized returns will depend on, among other factors, the value of assets and market conditions at the time of disposition, any related transaction costs, and the timing of the purchase. Indexes and benchmarks may not directly correlate or only partially relate to portfolios managed by SL Advisors as they have different underlying investments and may use different strategies or have different objectives than portfolios managed by SL Advisors (e.g. The Alerian index is a group MLP securities in the oil and gas industries. Portfolios may not include the same investments that are included in the Alerian Index. The S & P Index does not directly relate to investment strategies managed by SL Advisers.)

This site may contain forward-looking statements relating to the objectives, opportunities, and the future performance of the U.S. market generally. Forward-looking statements may be identified by the use of such words as; “believe,” “expect,” “anticipate,” “should,” “planned,” “estimated,” “potential” and other similar terms. Examples of forward-looking statements include, but are not limited to, estimates with respect to financial condition, results of operations, and success or lack of success of any particular investment strategy. All are subject to various factors, including, but not limited to general and local economic conditions, changing levels of competition within certain industries and markets, changes in interest rates, changes in legislation or regulation, and other economic, competitive, governmental, regulatory and technological factors affecting a portfolio’s operations that could cause actual results to differ materially from projected results. Such statements are forward-looking in nature and involves a number of known and unknown risks, uncertainties and other factors, and accordingly, actual results may differ materially from those reflected or contemplated in such forward-looking statements. Prospective investors are cautioned not to place undue reliance on any forward-looking statements or examples. None of SL Advisors LLC or any of its affiliates or principals nor any other individual or entity assumes any obligation to update any forward-looking statements as a result of new information, subsequent events or any other circumstances. All statements made herein speak only as of the date that they were made. r

Certain hyperlinks or referenced websites on the Site, if any, are for your convenience and forward you to third parties’ websites, which generally are recognized by their top level domain name. Any descriptions of, references to, or links to other products, publications or services does not constitute an endorsement, authorization, sponsorship by or affiliation with SL Advisors LLC with respect to any linked site or its sponsor, unless expressly stated by SL Advisors LLC. Any such information, products or sites have not necessarily been reviewed by SL Advisors LLC and are provided or maintained by third parties over whom SL Advisors LLC exercise no control. SL Advisors LLC expressly disclaim any responsibility for the content, the accuracy of the information, and/or quality of products or services provided by or advertised on these third-party sites.

All investment strategies have the potential for profit or loss. Different types of investments involve varying degrees of risk, and there can be no assurance that any specific investment will be suitable or profitable for a client’s investment portfolio.

Past performance of the American Energy Independence Index is not indicative of future returns.

Great article Simon! It gets a bit into weeds, but you need the details to understand the challenges! I will forward this to my “nerd” clients (IT and Engineers).

Good Job!

Marc

The goals of the UN show how fortunate we were to have stayed out of the League of Nations. Would that we could have repeated that wisdom with the UN.

From a JP Morgan Report on carbon capture:

The infrastructure required for meaningful geologic carbon sequestration would be enormous. In addition, the energy and materials requirements for direct air carbon capture are essentially unworkable. Here’s a quick summary of our conclusions on the topic from last year.

To sequester just 15%-20% of US CO2 emissions via traditional carbon capture and storage, the volume of US carbon sequestration (1.2 billion cubic meters) would need to exceed the volume of all US oil production in 2019 (858 billion cubic meters)/ That’s a LOT of infrastructure that does not exist.

Gathering and storing 25% of global CO2 through direct air carbon capture could require 40% or more of global electricity generation, even when assuming the presence of waste heat to power the carbon capture, requiring ~1,200 TWh per Gt of CO2. This is clearly an absurd proposition.

Here’s a great quip on the CCS fantasy:

One of the highest ratios in the world of energy science: the number of academic papers written on carbon sequestration divided by the actual amount of carbon sequestration (~0.1% of global emissions at last count).

I heard there is this new technology which is very efficient at removing CO2 from the atmosphere. I think they call it tree’s. Studies for example show one eucalyptus removes 25-30 tons of CO2 from the atmosphere per year depending on climate, and costs about $35. Assuming some economies of scale you are looking at a cost of roughly $1 per ton of CO2 removed annually.

Yes — the problem is it’s not a permanent CO2 removal. Once the tree dies it releases the CO2 back into the atmosphere. It can buy several decades though.