Why Are MLP Payouts So Confusing?

It’s surprisingly difficult to figure out what dividends are doing for midstream energy infrastructure. Just about every company has a free pass on cutting its payout nowadays. Prudent cash management isn’t going to draw much criticism with the size of the economic shock we’re enduring. Given the beating energy stocks suffered during 1Q20, a few dividend cuts would have been forgiven.

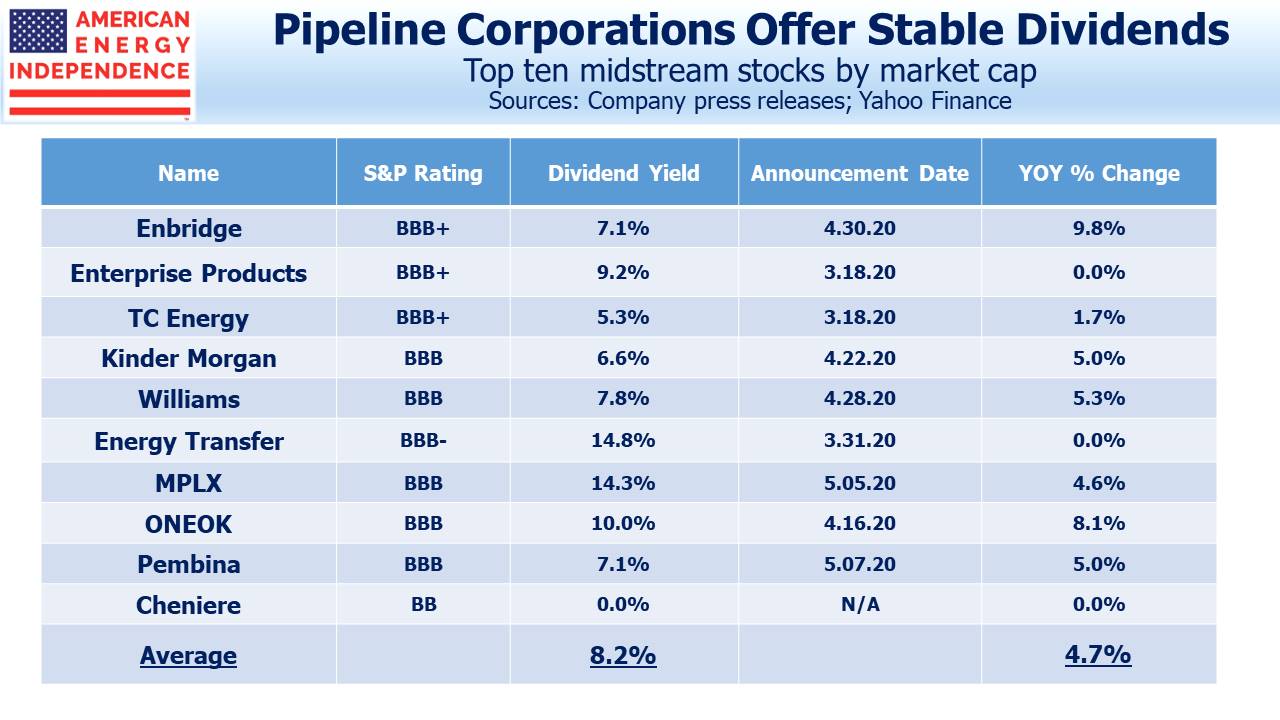

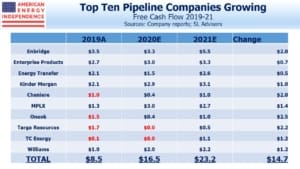

In spite of this, the biggest midstream energy infrastructure companies have maintained their payouts. In 1Q earnings calls, the overall message was that while it was hard to make confident long term forecasts, management teams felt comfortable with the resiliency of their businesses. The result is that the top ten midstream energy infrastructure companies by market cap have raised their payouts by an average of 4.7% over the past year.

None of them reduced dividends at their most recent announcement dates. Cheniere Energy, Inc. (LNG) doesn’t pay a dividend. Kinder Morgan (KMI) raised theirs by 5% compared to the prior quarter.

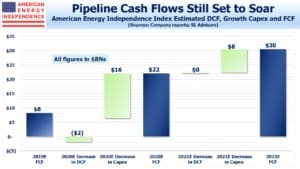

As we noted recently, free cash flow growth remains a positive story for these companies (see Pipeline Cash Flows Will Still Double This Year).

Alerian has echoed the positive news about distributions. They noted that, “The majority of midstream constituents grew or maintained dividends over 1Q19.” This was supported by a chart showing 68.5% of Alerian MLP Infrastructure Index (AMZI) components by market cap did just that. It sounds like a great story.

Unfortunately, characterizing distributions in this way presents a misleading picture. A majority maintaining or growing suggests that aggregate payouts for the group are similarly stable. They are not.

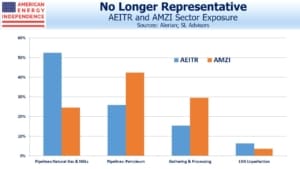

Distribution cuts at MLPs have been far more prevalent than at corporations – because the AMZI index consists of MLPs, it is more exposed to crude oil pipelines and to gathering and processing than the American Energy Independence Index (AEITR), which reflects the North American midstream sector as a whole. AMZI doesn’t reflect the industry. MLPs also tend to have lower credit ratings. As a consequence, MLP distributions are turning out to be less resilient than those paid by pipeline corporations.

Most companies tend to raise distributions/dividends gradually, by a few percent at time. By contrast, cuts are often 50-100%. So even though the majority of AMZI by market cap maintained or raised their distributions, the payout on the Alerian MLP ETF, AMLP, has just been cut again.

The AMZI is down to only 20 constituent companies now, and because 11 of them slashed their distributions, this was enough to force AMLP to cut its payout. This contrasts with the story for AMLP’s index, AMZI, which is being spun to sound superficially good.

It turns out that size matters. The three biggest MLPs, which are in the top ten midstream companies by market cap, all maintained or grew their payouts. The biggest companies in this sector tend to be more stable and have higher credit ratings.

AMLP investors care more about another cut than the spin being put on its index.

SL Advisors publishes the American Energy Independence Index

We are invested in KMI and LNG