Crude’s Drop Makes Higher Prices Likely

Crude oil just set a record of sorts, by falling for eleven consecutive days (as of this morning). Fears that sanctions on Iran would cause a supply shortage, leading to a price spike, now seem unfounded. Not long ago, many were surprised at the high degree of compliance. France’s energy giant Total’s CEO said it was, “…impossible for big energy firms to work in Iran.”

The big stick America wields on this issue is access to the U.S. financial system. If a company is deemed to be trading with Iran, it can find itself unable to conduct financial transactions in US$. This is a surprisingly powerful tool, since a substantial amount of trade is conducted in our currency. Total concluded that being unable to transact in US$ would be too disruptive to contemplate.

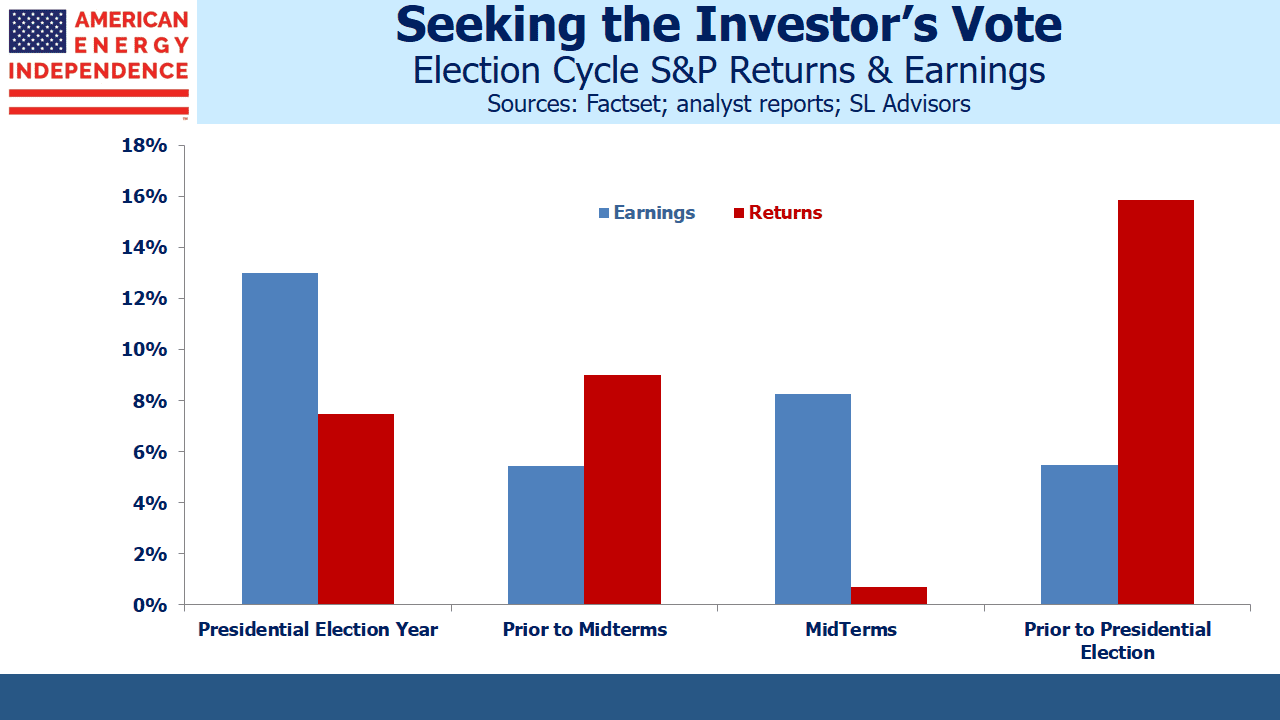

In the summer, the U.S. appeared to be taking an uncompromising approach, and Iranian crude exports were forecast to fall from 2.5 Million Barrels per Day (MMB/D) to as little as 1 MMB/D. Crude oil futures correspondingly rose. Pressure was put on Saudi Arabia to provide offsetting increased output, as the Administration fretted over high gasoline prices before the midterms.

More recently, waivers granted by the White House to eight importers of Iranian crude have calmed fears of a price spike. China and India, who are both continuing to buy Iranian crude as a result, imported over 1 MMB/D last year. As a result, the January ’19 Brent Crude month futures contract has slid from $86 in early October back to $68 where it was in the Spring. For now, it seems that the Iranian sanctions aren’t that significant.

Saudi Arabia probably expected the U.S. to be stricter in following through on sanctions, and was surprised by the waivers. They have just reduced December exports by 0.5 MMB/D. The Saudis surely expected to be selling oil at higher prices a month ago. Recent data shows that Saudi exports to the U.S. have been falling, and floating storage (i.e. crude on tankers in transit) is the lowest in four years. Some believe that Saudi Arabia is unable to sustain production above 10.6 MMB/D or so without damaging their oilfields.

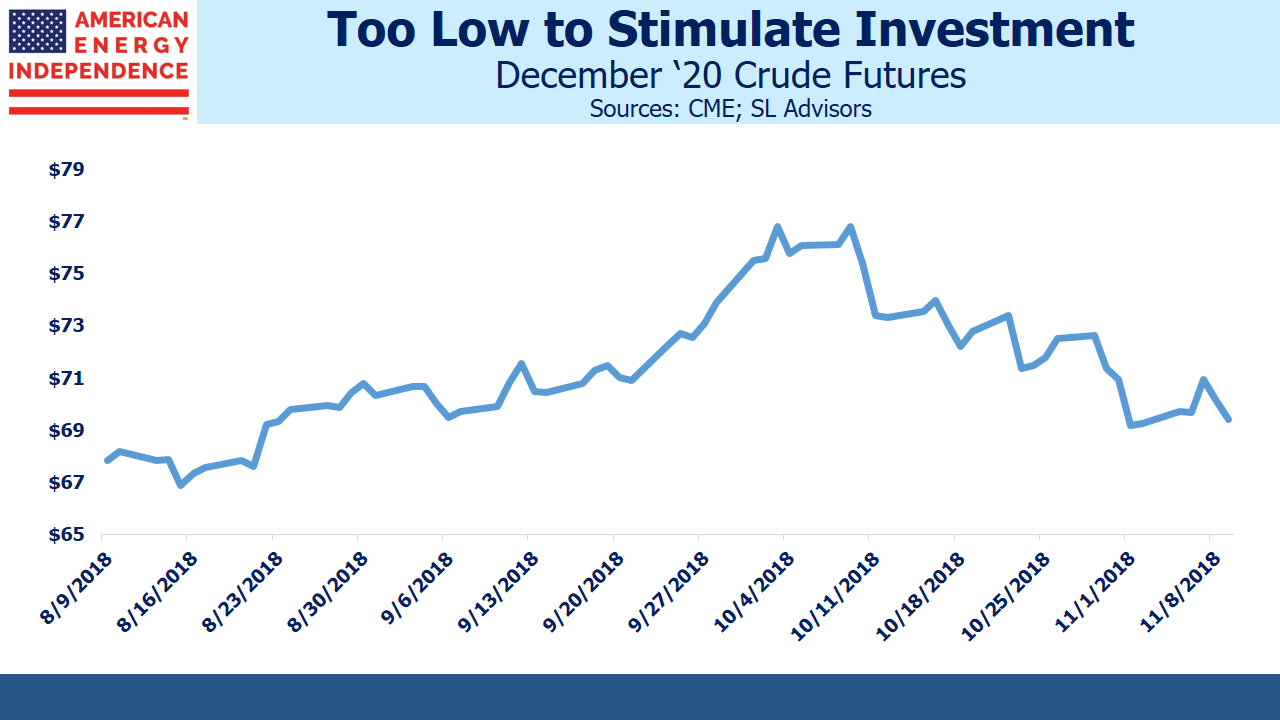

Although the gyrations of the front month futures contract have commanded attention, crude prices farther out have moved much less. The December ’20 futures contract fell from $76 to $70. Fear of sanctions had caused backwardation (near contracts higher than farther out ones), and this has corrected.

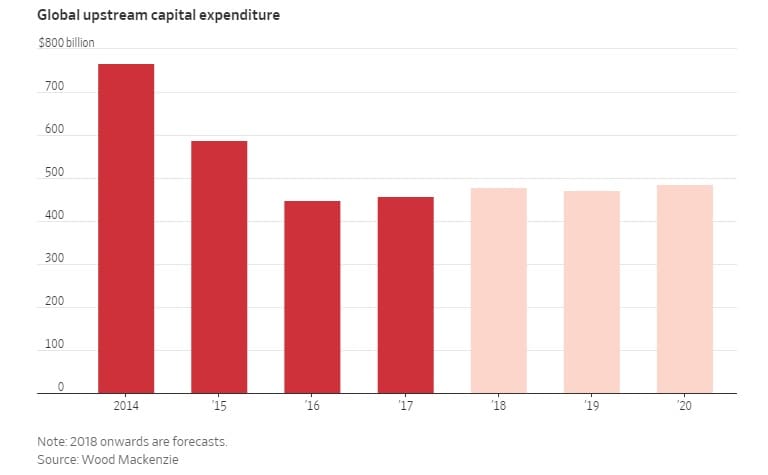

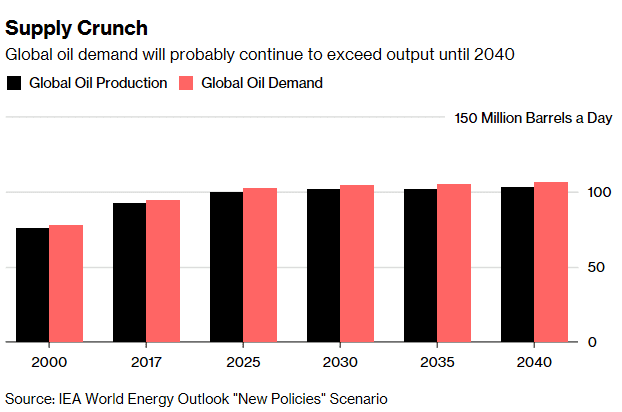

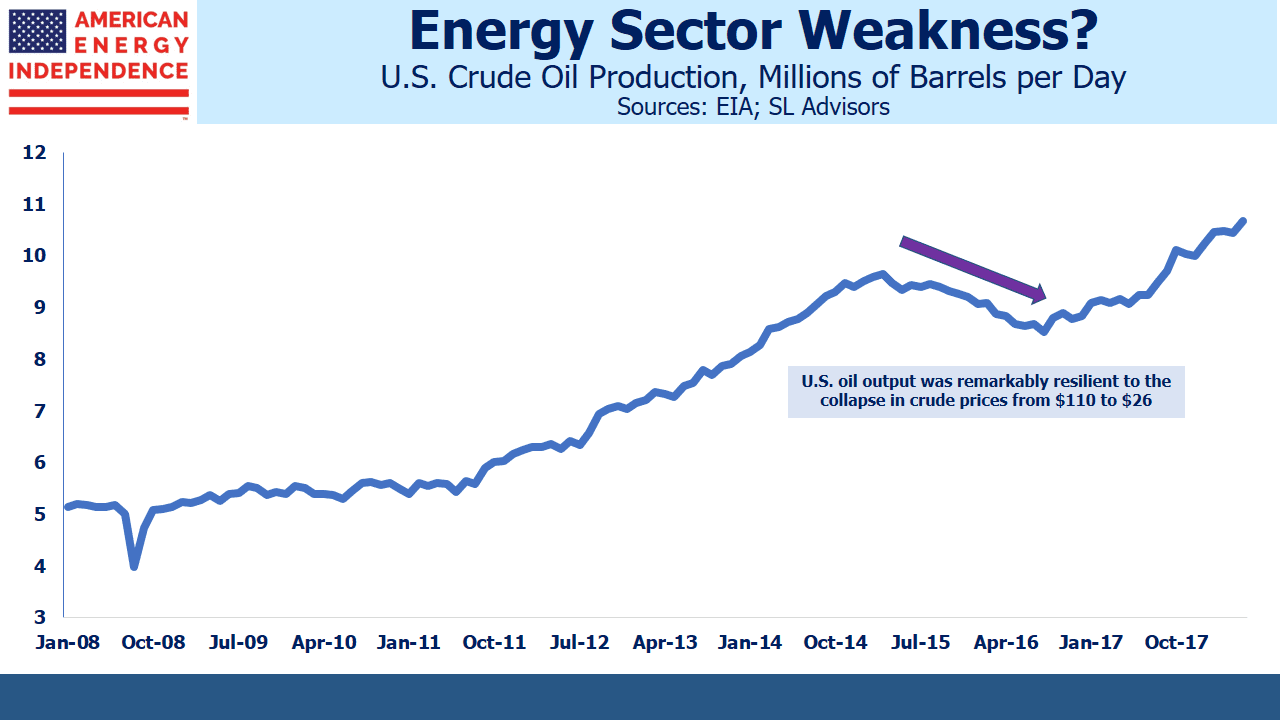

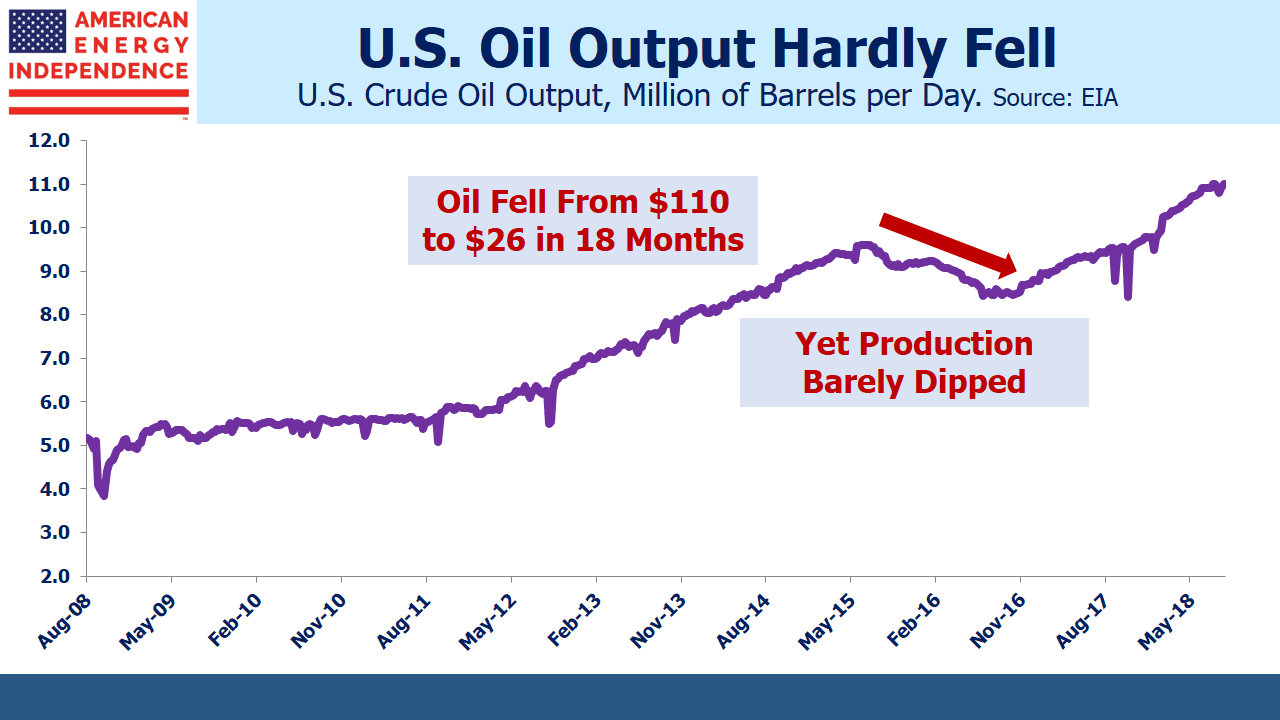

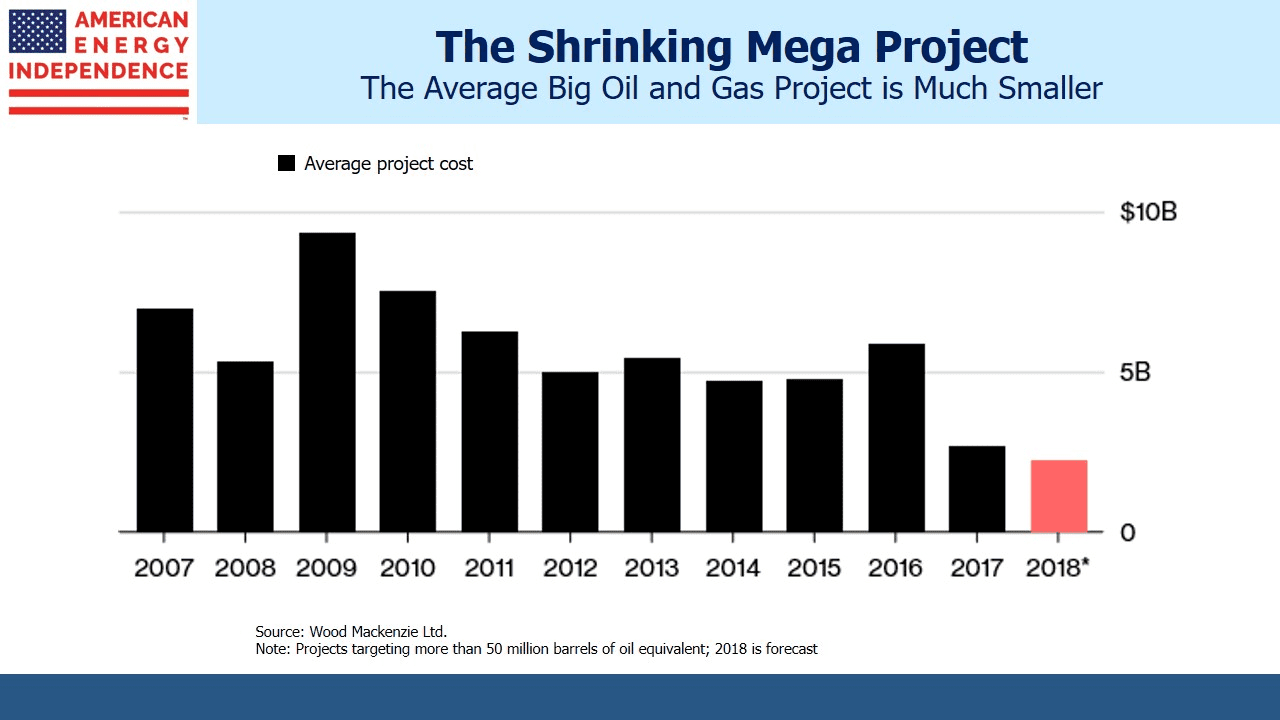

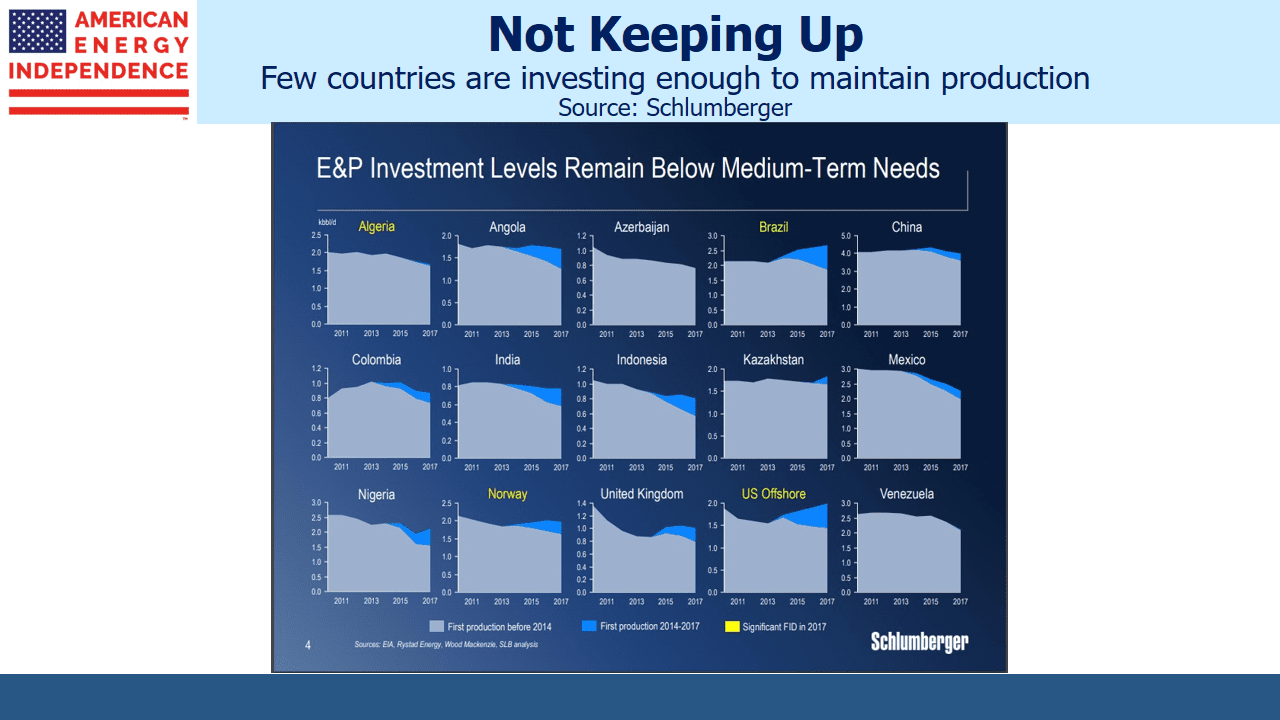

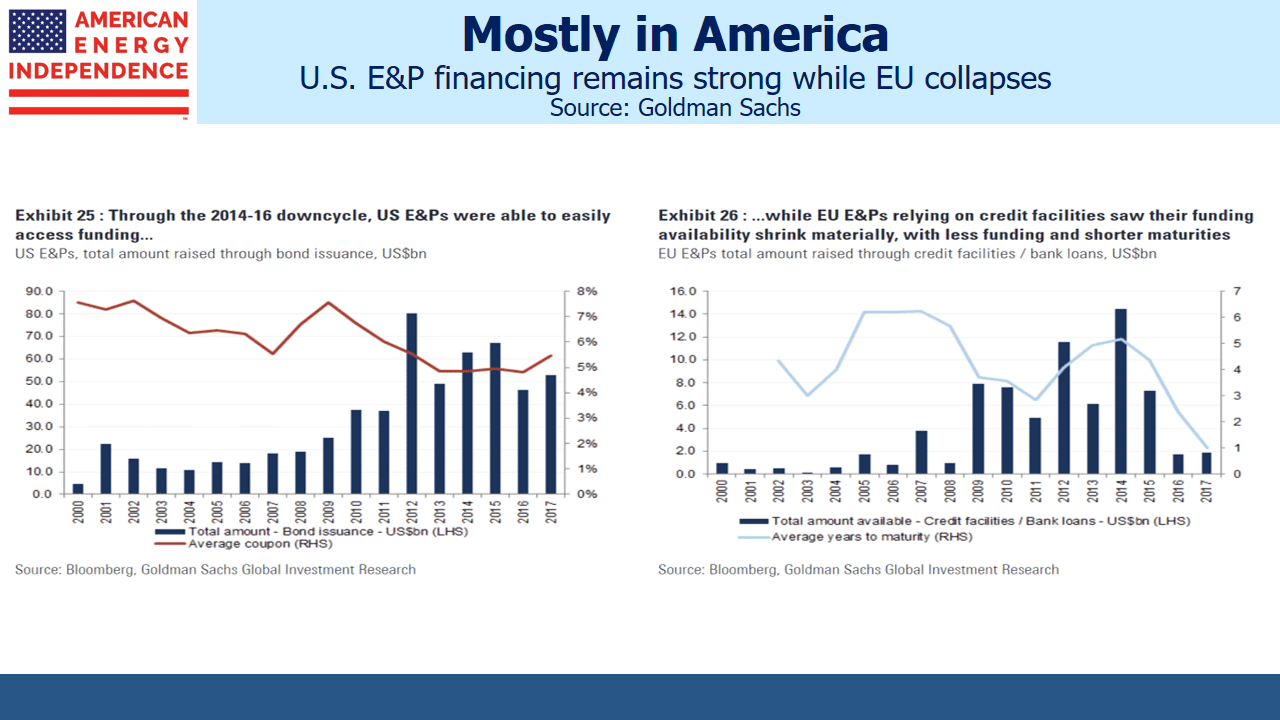

Investments in conventional oil production are driven by the price of crude expected to prevail over the life of the project. The front month gets the attention, but it doesn’t drive the decision. Because new oil projects take several years to reach production, many in the industry continue to worry that falling investment levels will eventually cause higher prices. The International Energy Agency (IEA) recently released their World Energy Outlook. They warn of a looming supply crunch, with the world seemingly too reliant on increasing U.S. production to meet demand growth. Investment spending collapsed during the 2015-16 industry downturn, and remains more than one third lower than it was in 2014. Discoveries of conventional hydrocarbon reserves are correspondingly down.

Crude oil along the futures curve is still at levels that have drawn repeated warnings of future supply shortfalls. Moreover, Saudi Arabia is finding that the U.S. administration ultimately wants low prices, with Trump recently tweeting, “Hopefully, Saudi Arabia and OPEC will not be cutting oil production. Oil prices should be much lower based on supply!” Expecting Americans to tolerate higher pump prices so as to pressure Iran is an unlikely strategy for any president to pursue. But Saudi Arabia needs higher prices to balance their budget. These conflicting goals will continue to impact oil prices.

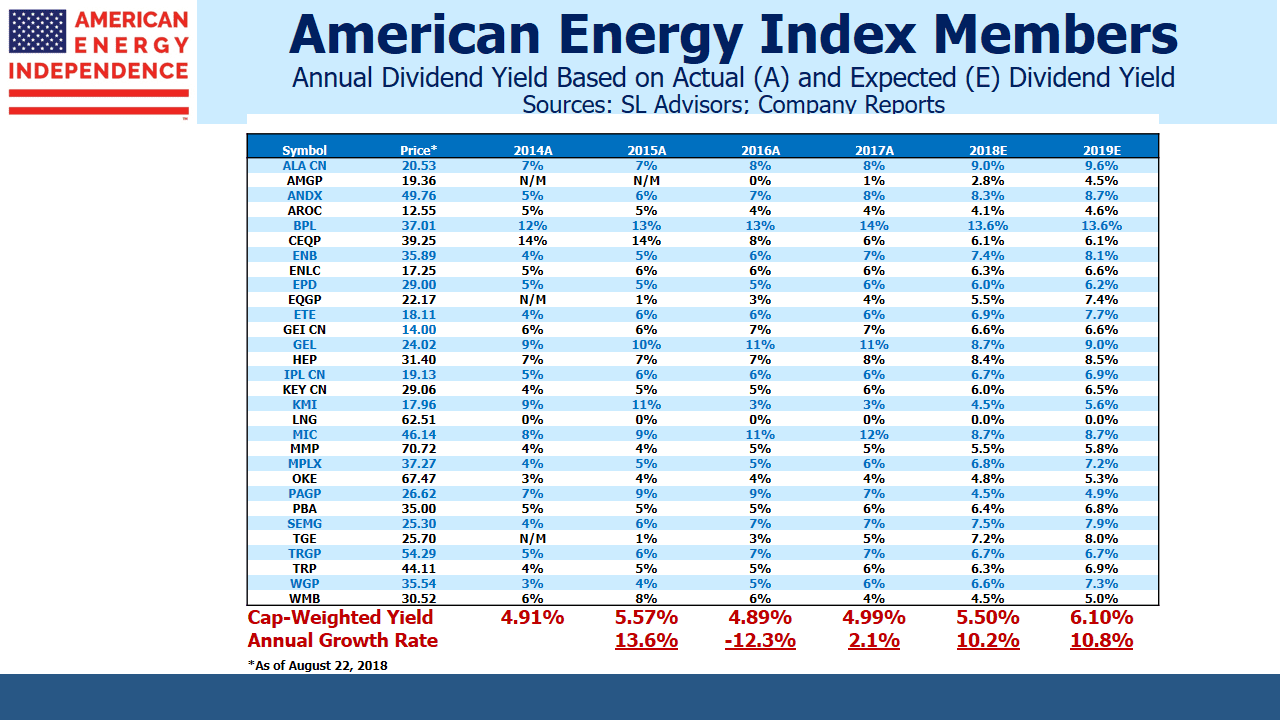

Low investment means higher prices are likely over the intermediate term; perhaps sooner, based on the drop in Saudi exports.