MLPs Feel the Love

The early part of 2017 has been kind to MLP investors. The generally reliable year-end effect has seen prices rise (see Give Your Loved One an MLP This Holiday Season). President Trump’s unabashedly supportive stance towards energy infrastructure has certainly helped sentiment, as have a number of corporate finance moves. The Alerian Index is up almost 8% so far this year (through Friday, February 3rd), as investors have acted on the positive news. MLP CEOs are Trump fans because they see lots of positives for their industry in his policies.

But behind the scenes, some of the C-corps whose General Partners (GPs) control their MLP are reassessing the GP/MLP financing model. In 2014 Kinder Morgan led the way by consolidating their structure. The MLP is a good place to hold eligible assets; the absence of a corporate tax liability (because MLPs are pass-through vehicles) lowers their cost of equity capital. Countless corporations over the years have “dropped down” energy infrastructure assets into an affiliated MLP in order to take advantage of this. However, the Shale Revolution has ironically challenged this model.

This is because the universe of MLP investors is limited to U.S. taxable investors. In practice, it’s further limited to high net worth (HNW) investors because the dreaded K-1s provided by MLPs (rather than 1099s as is the case with regular corporations) are only really acceptable to people who have an accountant prepare their tax return. Tax-exempt and non-U.S. investors face formidable tax barriers which largely eliminate their interest. Although investors in U.S. equities are mostly institutions from around the world, these considerations mean MLPs are mostly held by U.S. taxable, HNW, K-1 tolerant investors. This group is a small subset of the universe of global equity investors.

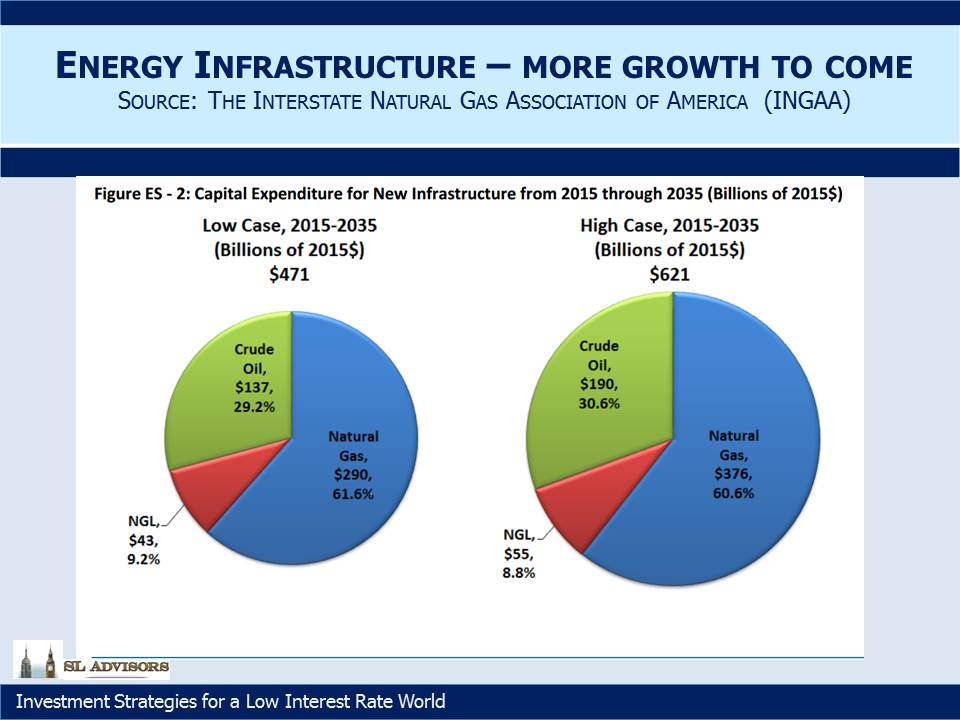

The Shale Revolution has created a need for substantial investments in America’s energy infrastructure (see the chart America’s Infrastructure – More Growth to Come in America Is Great!). Traditional MLP investors (U.S. taxable, HNW, K-1 tolerant) are not willing or able to provide the financing needed. This most obviously manifested itself in 2015 when MLP prices crashed under the weight of the need for growth capital (see The 2015 MLP Crash; Why and What’s Next). Kinder Morgan to some degree anticipated this when they simplified their structure. By moving their assets from Kinder Morgan Partners (KMP) to Kinder Morgan Inc. (KMI), they vastly increased their potential investor base.

In the process KMI took advantage of tax rules that allowed them to create a substantial tax shield. When they bought the assets from KMP, their value was stepped up from carrying value to current market. Normally, if Company A buys Company B for $100 and Company B’s book value is $60, the $40 premium to book value sits on Company A’s balance sheet as Goodwill. This is a balancing item, since you can’t spend or depreciate Goodwill. However, KMI showed that when buying a partnership (or more precisely, the assets held by the partnership), those assets are in effect revalued at $100 (using our prior example). There’s no Goodwill, simply assets whose carrying value is now their current market value. In the case of KMI, depreciation was then calculated from this higher level, allowing KMI to offset its taxable income with depreciation charges totaling $20BN over many years. The flip side of this was that KMP investors wound up with an unexpected tax bill. KMP was widely held by MLP investors, and this unwelcome tax surprise has left many with a bitter taste ever since. For more on this, see The Tax Story Behind Kinder Morgan’s Big Transaction.

Oneok (OKE) basically did the same thing last week when they bought up the units of Oneok Partners (OKS) that they didn’t already own, thus consolidating into a single entity. OKE has an estimated $14BN tax shield, helping to fuel faster growth since they’re not paying taxes for a few years. OKS investors will get an unwelcome tax bill just as was the case with KMP. It’s not a terrible transaction other than the pricing. Once again, the advice provided by their investment bank was poor. In fact, I’m reminded of Ronald Reagan’s quip that the nine most terrifying words in the English language are, “I’m from the government and I’m here to help.” If Reagan was an MLP investor today, he would update his warning to be, “I’m from Wall Street, and I’m here to help.”

MLPs have been the victims of so much bad advice lately from highly paid investment bankers that it’s hard to remember any actions that were the result of good advice. Most recently, OKE somehow convinced themselves that a 23% premium to the prior day’s close was an appropriate price at which to buy OKS units, even though they already owned 40% and controlled the entity. In this case, JPMorgan Securities and Morgan Stanley are the banks whose advice destroyed value for OKE. A premium of 5-10% would have been more than sufficient reward to OKS holders. They would have shared in the $14BN tax shield anyway through swapping their OKS units for shares in OKE. A big premium wasn’t necessary. Morgan Stanley investment bankers are active purveyors of wrongheadedness – only a few weeks ago their advice to Williams Companies (WMB) led to a sharp drop in their stock price when it emerged they’d given up their Incentive Distribution Rights (IDRs) too cheaply (see Williams Loses Its Way). WMB raised $1.9BN in equity which was then funneled to Williams Partners (WPZ), illustrating that they regard the C-corp as the better way to access investors but in the process weighing down the peer group of C-corps.

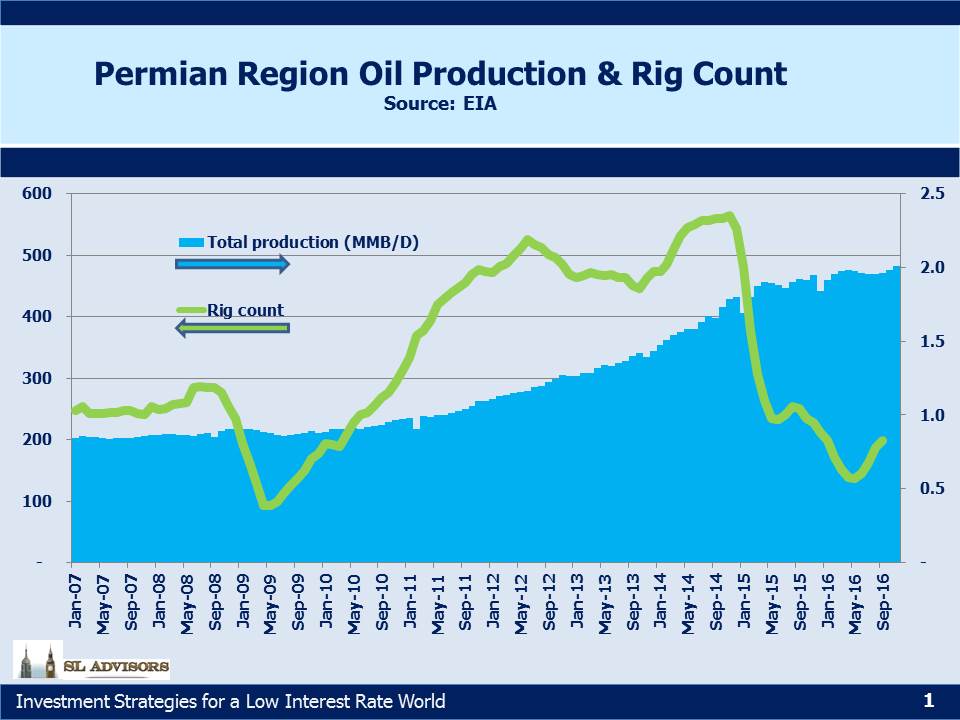

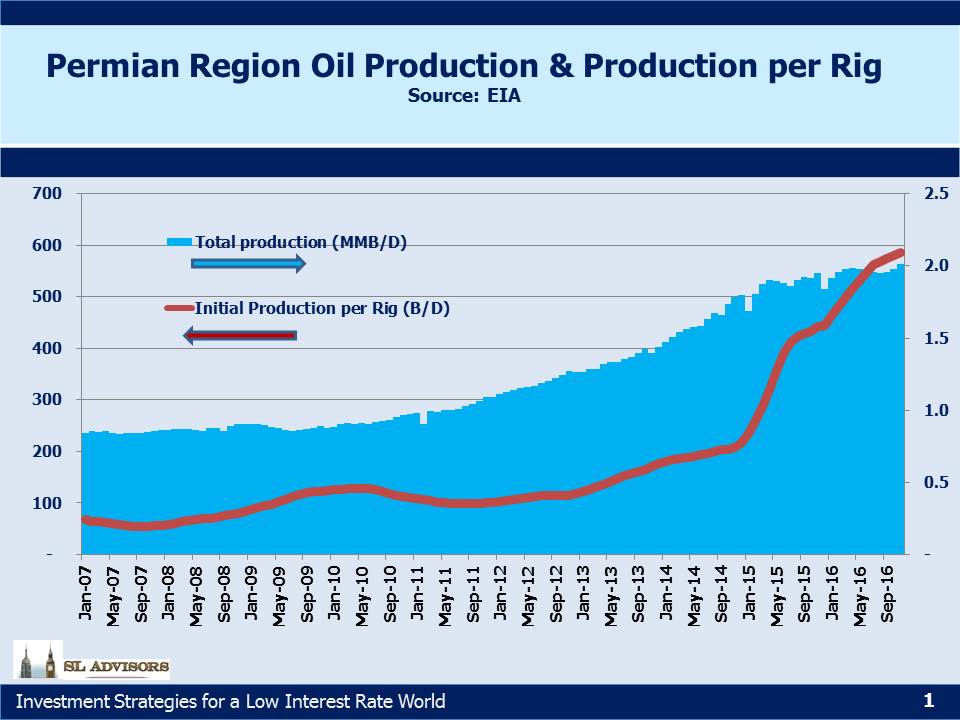

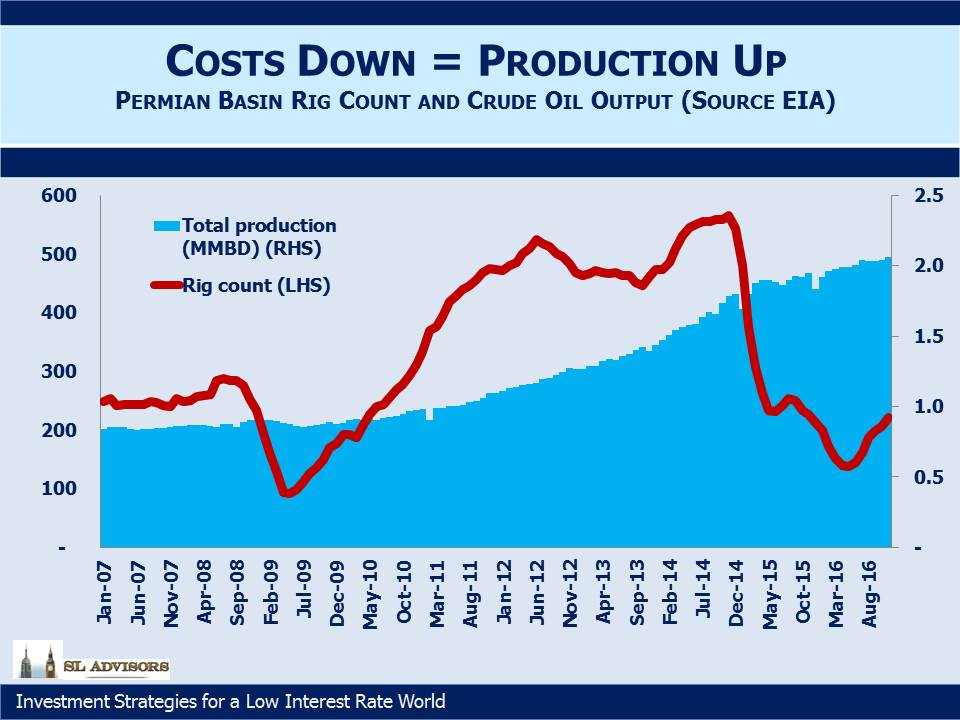

Putting aside the cost of lousy investment bankers, the theme behind these and other moves is that U.S. energy infrastructure has tremendous growth ahead of it. OKE and WMB are positioning themselves to be able to finance this growth in the most efficient way possible. They may in time need more financing than traditional MLP investors will provide. Other recent transactions, such as Plains All American’s (PAGP) $1.2BN investment in a Permian Basin gathering system, or Targa Resources Corp’s (TRGP) secondary offering to finance up to a $1.5BN investment (also in Permian gathering assets) similarly reflect growth opportunities. The market was non-plussed with both of these, in part because they involve new sales of stock by each company. But there are increasing signs that Permian crude oil output will challenge the existing take-away capacity from the region, improving the pricing power for those pipelines already in place.

In total, all this activity has been good for MLPs, thanks in part to Wall Street bankers guiding their pliant clients to overly-generous deal terms. Somewhat for the same reason, it has been less good for the C-corps that control these and other MLPs. However, the driver behind all this activity is the road that takes America to Energy Independence. Energy infrastructure managements are reconsidering the structure and making new investments precisely because of the growth opportunities they see. Through all this there is a certain life-cycle to the GP/MLP. Since it’s hard to do better than hold assets in a non-tax paying entity, the MLP is hard to beat:

- Energy corporation “drops down” assets to MLP it controls through its GP stake. GP earns IDRs, creating Hedge Fund Manager/Hedge Fund type relationship

- Combined enterprise grows and reaches point where IDR payments to GP start to drag on MLP cost of equity capital, and need for equity financing demands access to global equity investor base

- Corporation buys back MLP, acquiring assets whose carrying value has been depreciated down far below market. Resetting the assets allows depreciation from this higher level, eliminating tax obligation for some years which fuels faster cashflow growth while saddling MLP investors with unwelcome tax bill.

- As assets are depreciated down, holding assets in the corporation becomes less efficient as they start owing taxes again. Creating an MLP (Version 2) becomes increasingly attractive.

- Return to #1

The largest energy infrastructure businesses are concluding that they need to be a corporation. If the balance sheet value of their assets is high enough the resulting depreciation charge can, for a time, offset their taxable income. A non-tax paying C-corp can be preferable to an MLP, because you can access more investors. But in time the depreciation charge loses its ability to offset taxable income. At that time you might see some of these companies create MLPs again, repeating the cycle.

The GP/MLP structure remains attractive for a great many businesses whose enterprise value is below the $30BN or so level at which size seems to become an issue. And because of the tax shield, the bigger firms are finding ways to hold infrastructure assets with many of the advantages of an MLP. Whether held in a C-corp or MLP, America’s energy infrastructure is largely exempt from paying corporate taxes, allowing more of the returns to flow to the owners.

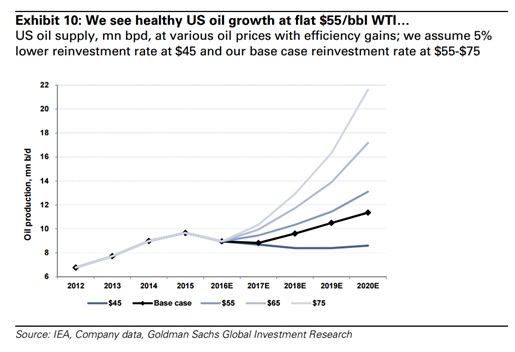

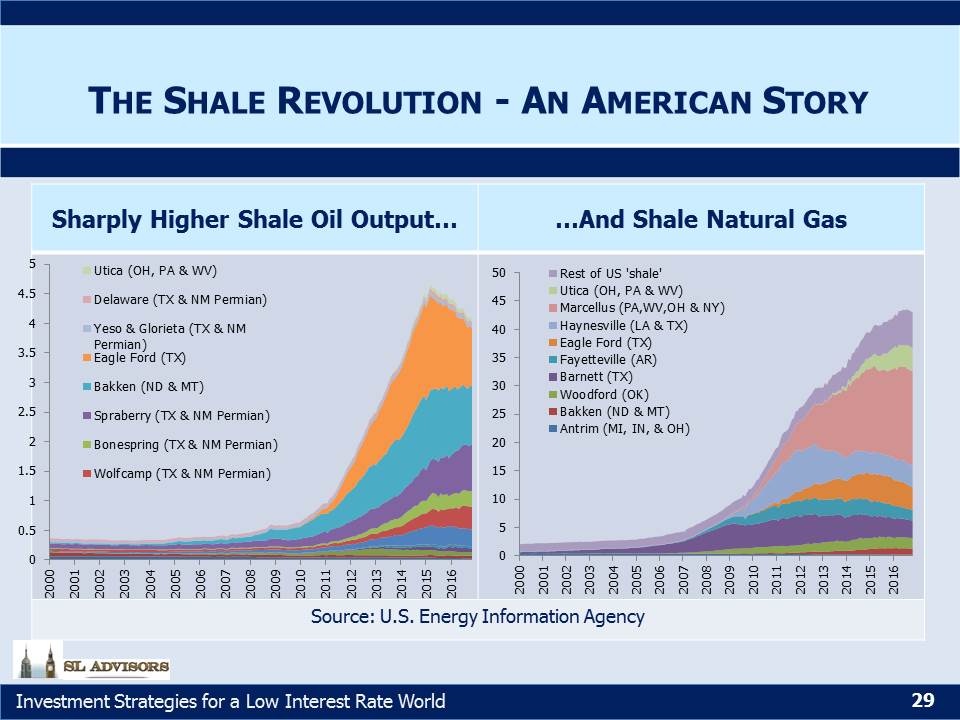

he success of horizontal drilling and hydraulic fracturing (“fracking”) in the U.S. was releasing increasing amounts of crude oil from hitherto impenetrable porous rock. A consequence was that from 2011-2014 fully all of the increase in global demand for crude oil had been met by North American production (see

he success of horizontal drilling and hydraulic fracturing (“fracking”) in the U.S. was releasing increasing amounts of crude oil from hitherto impenetrable porous rock. A consequence was that from 2011-2014 fully all of the increase in global demand for crude oil had been met by North American production (see

Shale oil and gas production are upending the energy markets. The U.S. is not just the leader in this new technology, it’s virtually the only game in town. Oil, natural gas liquids and natural gas are known to exist in porous rock all over the

Shale oil and gas production are upending the energy markets. The U.S. is not just the leader in this new technology, it’s virtually the only game in town. Oil, natural gas liquids and natural gas are known to exist in porous rock all over the